Boston Blackie (1944, 1945-1950) aired “Jailbirds Murdoch and Dawson” on February 11, 1947 as the 96th broadcast of the estimated 220 from its 1945-1950 run. This is but the fifth episode of Boston Blackie we have featured, the first in 2018 and the last coming in July of 2022, so for newcomers I recap below the rather fascinating history of the man behind the stories that eventually led to Boston Blackie coming to radio, film, and even early television. The show was produced originally in 1944 as a 13-episode summer replacement for the Amos & Andy Show. It proved popular enough and aired its first show in April of 1945, but under different ownership (ZIV productions, running on NBC in its own time slot), format, and actors. Chester Morris played Boston Blackie while Richard Lane played the part of Inspector Farraday in the 1944 replacement episodes, though in its official 1945 incarnation Richard Kollmar (1910-1971, photo middle right) became Boston Blackie, primarily due to contractual film obligations that stood in the way of Chester Morris continuing the role.

Boston Blackie (1944, 1945-1950) aired “Jailbirds Murdoch and Dawson” on February 11, 1947 as the 96th broadcast of the estimated 220 from its 1945-1950 run. This is but the fifth episode of Boston Blackie we have featured, the first in 2018 and the last coming in July of 2022, so for newcomers I recap below the rather fascinating history of the man behind the stories that eventually led to Boston Blackie coming to radio, film, and even early television. The show was produced originally in 1944 as a 13-episode summer replacement for the Amos & Andy Show. It proved popular enough and aired its first show in April of 1945, but under different ownership (ZIV productions, running on NBC in its own time slot), format, and actors. Chester Morris played Boston Blackie while Richard Lane played the part of Inspector Farraday in the 1944 replacement episodes, though in its official 1945 incarnation Richard Kollmar (1910-1971, photo middle right) became Boston Blackie, primarily due to contractual film obligations that stood in the way of Chester Morris continuing the role.

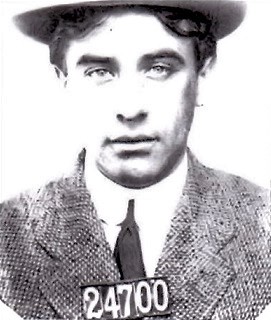

The Boston Blackie character first appeared in a series of short stories, the first in 1914 in The American Magazine by author Jack Boyle (1881-1928, photo top right). Boyle led a short but colorful life, spending two stints in prison for passing bad checks and forgery. Details of his life between the years 1908 and 1914, according to this website, are scarce, though through diligent research and some luck it was discovered that Boyle spent 10 months in San Quentin (mug shot top right) beginning on December 17, 1910 and was released the following October; though a few years later in 1914 he would be serving another stint in the joint, this time in a Colorado state prison for much the same offenses.

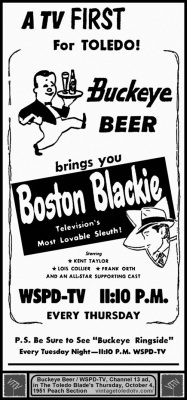

Turning what he knew into what he would write, Boyle then created the fictional character of Boston Blackie, a reformed jewel thief and safe-cracker who had done prison time and was now an “Enemy to those who make him an enemy. Friend to those who have no friend.” Blackie is aided in his capers by his rather slow-witted sidekick Runt, and is hounded by police Inspector Farraday (the police inspector working against, or trying to pin the blame for crimes against the hero being a popular formula that became a staple, i.e. The Shadow, Rocky Jordan, The Green Hornet, and many others in print, radio, and film). Boyle’s stories hit the right chord and a whopping 11 silent films featuring Blackie were made from 1918-1927. The series was picked up in 1941 with Chester Morris in the lead as Blackie in Meet Boston Blackie, the first of what would be 14 total films, the final one to hit the silver screen in 1949 and all starring Chester Morris. When the new medium of television became all the rage Boston Blackie was among the first to jump on board with Boston Blackie. It debuted in 1951, ran for 58 half-hour episodes until 1953, and would then air in syndication for almost another ten years. An interesting side note is that of Blackie’s 58 TV shows 32 were shot in color, while the remaining 26 were shot in black & white, shooting in color something unheard of at the time (and expensive) for an early television show. But the producers were ahead of their time and gambled that when color became more widely available there would be a market for color reruns. Thus, Boston Blackie would join the ranks of the few early TV shows also shot at least in part in color, Superman and The Cisco Kid two favorites coming to mind.

Turning what he knew into what he would write, Boyle then created the fictional character of Boston Blackie, a reformed jewel thief and safe-cracker who had done prison time and was now an “Enemy to those who make him an enemy. Friend to those who have no friend.” Blackie is aided in his capers by his rather slow-witted sidekick Runt, and is hounded by police Inspector Farraday (the police inspector working against, or trying to pin the blame for crimes against the hero being a popular formula that became a staple, i.e. The Shadow, Rocky Jordan, The Green Hornet, and many others in print, radio, and film). Boyle’s stories hit the right chord and a whopping 11 silent films featuring Blackie were made from 1918-1927. The series was picked up in 1941 with Chester Morris in the lead as Blackie in Meet Boston Blackie, the first of what would be 14 total films, the final one to hit the silver screen in 1949 and all starring Chester Morris. When the new medium of television became all the rage Boston Blackie was among the first to jump on board with Boston Blackie. It debuted in 1951, ran for 58 half-hour episodes until 1953, and would then air in syndication for almost another ten years. An interesting side note is that of Blackie’s 58 TV shows 32 were shot in color, while the remaining 26 were shot in black & white, shooting in color something unheard of at the time (and expensive) for an early television show. But the producers were ahead of their time and gambled that when color became more widely available there would be a market for color reruns. Thus, Boston Blackie would join the ranks of the few early TV shows also shot at least in part in color, Superman and The Cisco Kid two favorites coming to mind.

This engaging episode begins with the ruthless killers of the title being surprised and captured by the police. After they are cuffed and being hauled off to jail they promise Inspector Farraday in no uncertain terms that no jail will ever hold them. An empty bit of braggadocio by a pair of society’s lowest scum, or a promise soon to be fulfilled? Unfortunately, the latter soon becomes the case and Murdoch and Dawson are holed up where no one can find them. They await orders from their gang, though not even their fellow criminals know their whereabouts. The second storyline of this noir adventure is then introduced when a popular radio singer calls Blackie seeking his help after getting a threatening note from an anonymous source. Before the singer can explain to Blackie the particulars of the threat he is roughed up by thugs. Somehow the threat to the radio singer and the escaped murderers end up being connected, but how? Follow the dual storylines carefully and you will unlock the code to this down and dirty caper involving Blackie, the police, and the dangerous “Jailbirds Murdoch and Dawson.”

(The linked CD at top includes this episode and 19 more.)

Play Time: 27:39

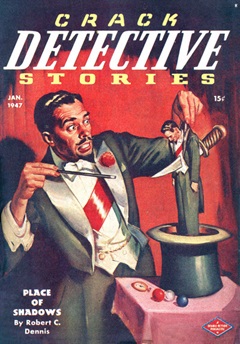

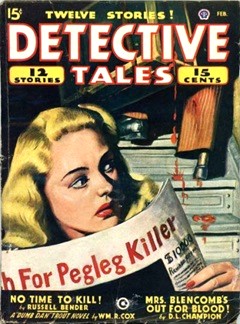

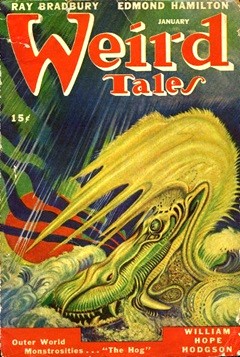

{Though Boston Blackie bounced around and aired on different days during its run, in February of 1947 it aired from 7:30-8 PM on Tuesday evenings, plenty early enough for the gang to give this episode a listen and vow to meet up at the corner newsstand the following afternoon after school. There would be no dearth of detective pulps from which they would find worthwhile stories with the police or private detectives chasing down and defeating the dregs of the underworld, a few of which are displayed below. Crack Detective Stories (1941-57) would survive 8 title changes over its 16-year life, and while not regarded as one of the top tier of detective pulps, managed to hold its devoted audience for almost 100 issues. It was a bi-monthly in 1947. Detective Tales (1935-53) was another long-lived detective pulp. With an unbroken monthly schedule through 1950, it dropped to a bi-monthly for its final couple of years. Overall, it would publish 202 issues. While not a detective pulp, the gold standard of dark fantasy fare, Weird Tales (1923-54), took its fearless readers to dark worlds and supernatural realms that not even noir pulp stories could match. The horrors it offered on a regular basis, by many of the most skilled horror authors in the field, far outstripped any comparable thrill derived from the detective magazines. A fine example is shown below, with cover stories by none other than Ray Bradbury, Edmond Hamilton, and William Hope Hadgson. WT was a bi-monthly in 1947.}

[Left: Crack Detective, 1/47 – Center: Detective Tales, 2/47 – Right: Weird Tales, 1/47]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.