Boston Blackie (1944, 1945-1950) aired “Blackie Breaks into Prison” on May 21, 1947 as the 123rd broadcast of the estimated 220 from its 1945-1950 run. This is but the seventh Boston Blackie episode we have featured, the first in 2018 with this being only the third since July of 2022, so for newcomers I recap below the rather fascinating history of the man behind the stories that eventually led to Boston Blackie coming to radio, film, and even early television. The show was produced originally in 1944 as a 13-episode summer replacement for the Amos & Andy Show. It proved popular enough and aired its first show in April of 1945, but under different ownership (ZIV productions, running on NBC in its own time slot), format, and actors. Chester Morris played Boston Blackie while Richard Lane played the part of Inspector Farraday in the 1944 replacement episodes, though in its official 1945 incarnation Richard Kollmar (1910-1971, photo middle right) became Boston Blackie, primarily due to contractual film obligations that stood in the way of Chester Morris continuing the role.

Boston Blackie (1944, 1945-1950) aired “Blackie Breaks into Prison” on May 21, 1947 as the 123rd broadcast of the estimated 220 from its 1945-1950 run. This is but the seventh Boston Blackie episode we have featured, the first in 2018 with this being only the third since July of 2022, so for newcomers I recap below the rather fascinating history of the man behind the stories that eventually led to Boston Blackie coming to radio, film, and even early television. The show was produced originally in 1944 as a 13-episode summer replacement for the Amos & Andy Show. It proved popular enough and aired its first show in April of 1945, but under different ownership (ZIV productions, running on NBC in its own time slot), format, and actors. Chester Morris played Boston Blackie while Richard Lane played the part of Inspector Farraday in the 1944 replacement episodes, though in its official 1945 incarnation Richard Kollmar (1910-1971, photo middle right) became Boston Blackie, primarily due to contractual film obligations that stood in the way of Chester Morris continuing the role.

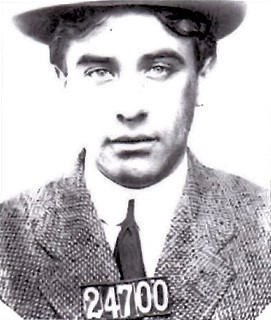

The Boston Blackie character first appeared in a series of short stories, the first in 1914 in The American Magazine by author Jack Boyle (1881-1928, photo top right). Boyle led a short but colorful life, spending two stints in prison for passing bad checks and forgery. Details of his life between the years 1908 and 1914, according to this website, are scarce, though through diligent research and some luck it was discovered that Boyle spent 10 months in San Quentin (mug shot top right) beginning on December 17, 1910 and was released the following October, though a few years later in 1914 he would

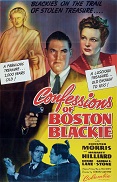

be serving another stint in the joint, this time in a Colorado state prison for much the same offenses.Turning what he knew into what he would write, Boyle then created the fictional character of Boston Blackie, a reformed jewel thief and safe-cracker who had done prison time and was now an “Enemy to those who make him an enemy. Friend to those who have no friend.” Blackie is aided in his capers by his rather slow-witted sidekick Runt, and is hounded by police Inspector Farraday (the police inspector working against, or trying to pin the blame for crimes against the hero being a popular formula that became a staple, i.e. The Shadow, Rocky Jordan, The Green Hornet, and many others in print, radio, and film). Boyle’s stories hit the right chord and a whopping 11 silent films featuring Blackie were made from 1918-1927. The series was picked up in 1941 with Chester Morris in the lead as Blackie in Meet Boston Blackie, the first of what would be 14 total films, the final one to hit the silver screen in 1949 and all starring Chester Morris. When the new medium of television became all the rage Boston Blackie was among the first to jump on board with Boston Blackie. It debuted in 1951, ran for 58 half-hour episodes until 1953, and would then air in syndication for almost another ten years. An interesting side note is that of Blackie’s 58 TV shows 32 were shot in color, while the remaining 26 were shot in black & white, shooting in color something unheard of at the time (and expensive) for an early television show. But the producers were ahead of their time and gambled that when color became more widely available there would be a market for color reruns. Thus, Boston Blackie would join the ranks of the few early TV shows also shot at least in part in color, Superman and The Cisco Kid two favorites coming to mind.

be serving another stint in the joint, this time in a Colorado state prison for much the same offenses.Turning what he knew into what he would write, Boyle then created the fictional character of Boston Blackie, a reformed jewel thief and safe-cracker who had done prison time and was now an “Enemy to those who make him an enemy. Friend to those who have no friend.” Blackie is aided in his capers by his rather slow-witted sidekick Runt, and is hounded by police Inspector Farraday (the police inspector working against, or trying to pin the blame for crimes against the hero being a popular formula that became a staple, i.e. The Shadow, Rocky Jordan, The Green Hornet, and many others in print, radio, and film). Boyle’s stories hit the right chord and a whopping 11 silent films featuring Blackie were made from 1918-1927. The series was picked up in 1941 with Chester Morris in the lead as Blackie in Meet Boston Blackie, the first of what would be 14 total films, the final one to hit the silver screen in 1949 and all starring Chester Morris. When the new medium of television became all the rage Boston Blackie was among the first to jump on board with Boston Blackie. It debuted in 1951, ran for 58 half-hour episodes until 1953, and would then air in syndication for almost another ten years. An interesting side note is that of Blackie’s 58 TV shows 32 were shot in color, while the remaining 26 were shot in black & white, shooting in color something unheard of at the time (and expensive) for an early television show. But the producers were ahead of their time and gambled that when color became more widely available there would be a market for color reruns. Thus, Boston Blackie would join the ranks of the few early TV shows also shot at least in part in color, Superman and The Cisco Kid two favorites coming to mind.

“Blackie Breaks into Prison” begins with a most unusual scene with Blackie hacking and sawing his way into a prison in the dead of night. Not only does this seem a highly ineffective enterprise, begging us to suspend our disbelief, but begs the obvious question as to just Why he would do such a thing. He succeeds, of course, but at the same time as he breaks into the joint a prisoner in a far removed cell is murdered—and wouldn’t you know it, Blackie’s unorthodox break in is discovered and he is held as an obvious suspect in the murder. After this quick jump start to the story, the remainder of the tale unfolds exclusively behind prison bars. We are given information and clues when necessary and eventually learn the quirky ins and outs of why Blackie broke into the prison, who murdered the prisoner and why, and Blackie’s relationship to the deceased jailbird. While it deals with a serious matter, the oddball first scene captures our attention and propels us into the heart of the story, setting the stage as but one of several attention grabbers that lead us to the real reason “Blackie Breaks into Prison.”

(The linked CD at top includes this episode and 19 more, all digitally restored and remastered.)

Play Time: 26:43

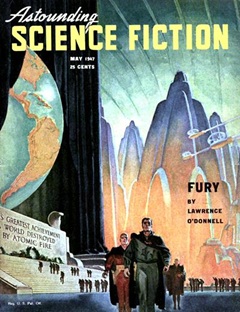

{“Blackie Breaks into Prison” was all the incentive the neighborhood gang needed to head for the corner newsstand the next afternoon after school, hunting for more dramatic fare of the kind that had excited them the night before. Astounding SF (1930-present, now Analog) filled the bill nicely, especially with a new story by Lawrence O’Donnell, one of the pseudonyms of popular author Henry Kuttner, though this was a collaboration with Kuttner’s wife and writing partner C. L. Moore (Kuttner writing the much greater proportion of this particular book). ASF held to its long standing monthly schedule in 1947. Street & Smith’s Detective Story (1915-49) was the first pulp in history devoted exclusively to detective fiction, adding its publisher’s name to the title with the February 21, 1931 issue. It was a monthly in 1947, that year being its last with a full monthly schedule. New Detective (1941-53) featured pretty much standard fare, but with an emphasis on police detective stories penned by a number of the most popular writers of the time. Aside from two very brief blips, it maintained a bi-monthly schedule throughout its run, including 1947.}

[Left: Astounding SF, 5/47 – Center: Detective Story, 5/47 – Right: New Detective, 5/47]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.