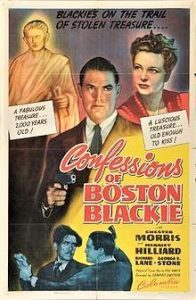

Boston Blackie (1944, 1945-1950) aired “Hypnotic Murder” on August 6, 1945 as the 18th broadcast of the estimated 220 from its 1945-1950 run. This is but the third of this program we have showcased here, the last coming almost two years ago in January of 2019, so for newcomers I recap the rather fascinating history of the man behind the stories that eventually led to Boston Blackie coming to radio, film, and even early television. The show was produced originally in 1944 as a 13-episode summer replacement for the Amos & Andy Show. It proved popular enough and aired its first show in April of 1945, but under different ownership (ZIV productions, running on NBC in its own time slot), format, and actors. Chester Morris played Boston Blackie while Richard Lane played the part of Inspector Farraday in the 1944 replacement episodes, though in its official 1945 incarnation Richard Kollmar (1910-1971, photo middle right) became Boston Blackie, primarily due to contractual film obligations that stood in the way of Chester Morris continuing the role.

Boston Blackie (1944, 1945-1950) aired “Hypnotic Murder” on August 6, 1945 as the 18th broadcast of the estimated 220 from its 1945-1950 run. This is but the third of this program we have showcased here, the last coming almost two years ago in January of 2019, so for newcomers I recap the rather fascinating history of the man behind the stories that eventually led to Boston Blackie coming to radio, film, and even early television. The show was produced originally in 1944 as a 13-episode summer replacement for the Amos & Andy Show. It proved popular enough and aired its first show in April of 1945, but under different ownership (ZIV productions, running on NBC in its own time slot), format, and actors. Chester Morris played Boston Blackie while Richard Lane played the part of Inspector Farraday in the 1944 replacement episodes, though in its official 1945 incarnation Richard Kollmar (1910-1971, photo middle right) became Boston Blackie, primarily due to contractual film obligations that stood in the way of Chester Morris continuing the role.

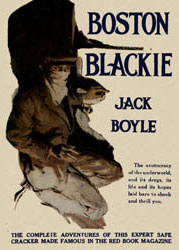

The Boston Blackie character first appeared in a series of short stories, the first in 1914 in The American Magazine by author Jack Boyle (1881-1928, photo top right). Boyle led a short but colorful life, spending two stints in prison for passing bad checks and forgery. Details of his life between the years 1908 and 1914, according to this website, are scarce, though through diligent research and some luck it was discovered that Boyle spent 10 months in San Quentin (mug shot top right) beginning on December 17, 1910 and was released the following October; though a few years later in 1914 he would be serving another stint in the joint, this time in a Colorado state prison for much the same offenses.

Turning what he knew into what he would write, Boyle then created the fictional character of Boston Blackie, a reformed jewel thief and safe-cracker who had done prison time and was now an “Enemy to those who make him an enemy. Friend to those who have no friend.” Blackie is aided in his capers by his rather slow-witted sidekick Runt, and is hounded by police Inspector Farraday (the police inspector working against, or trying to pin the blame for crimes against the hero being a popular formula that became a staple, i.e. The Shadow, Rocky Jordan, The Green Hornet, and many others in print, radio, and film). Boyle’s stories hit the right chord and a whopping 11 silent films featuring Blackie were made from 1918-1927. The series was picked up in 1941 with Chester Morris in the lead as Blackie in Meet Boston Blackie, the first of what would be 14 total films, the final one to hit the silver screen in 1949 and all starring Chester Morris. When the new medium of television became all the rage Boston Blackie was among the first to jump on board with Boston Blackie. It debuted in 1951, ran for 58 half-hour episodes until 1953, and would then air in syndication for almost another ten years. An interesting side note is that of Blackie’s 58 TV shows 32 were shot in color, while the remaining 26 were shot in black & white, shooting in color something unheard of at the time (and expensive) for an early television show. But the producers were ahead of their time and gambled that when color became more widely available there would be a market for color reruns. Thus, Boston Blackie would join the ranks of the few early TV shows also shot at least in part in color, Superman and The Cisco Kid two favorites coming to mind.

Turning what he knew into what he would write, Boyle then created the fictional character of Boston Blackie, a reformed jewel thief and safe-cracker who had done prison time and was now an “Enemy to those who make him an enemy. Friend to those who have no friend.” Blackie is aided in his capers by his rather slow-witted sidekick Runt, and is hounded by police Inspector Farraday (the police inspector working against, or trying to pin the blame for crimes against the hero being a popular formula that became a staple, i.e. The Shadow, Rocky Jordan, The Green Hornet, and many others in print, radio, and film). Boyle’s stories hit the right chord and a whopping 11 silent films featuring Blackie were made from 1918-1927. The series was picked up in 1941 with Chester Morris in the lead as Blackie in Meet Boston Blackie, the first of what would be 14 total films, the final one to hit the silver screen in 1949 and all starring Chester Morris. When the new medium of television became all the rage Boston Blackie was among the first to jump on board with Boston Blackie. It debuted in 1951, ran for 58 half-hour episodes until 1953, and would then air in syndication for almost another ten years. An interesting side note is that of Blackie’s 58 TV shows 32 were shot in color, while the remaining 26 were shot in black & white, shooting in color something unheard of at the time (and expensive) for an early television show. But the producers were ahead of their time and gambled that when color became more widely available there would be a market for color reruns. Thus, Boston Blackie would join the ranks of the few early TV shows also shot at least in part in color, Superman and The Cisco Kid two favorites coming to mind.

“Hypnotic Murder” involves a nightclub cigarette girl who confesses to murder, Boston Blackie who inexplicably removes the murder weapon from the scene thus committing a crime himself, and some of the usual complications blocking his way to the solving of a crime. Why did the cigarette girl confess to a murder she may not have committed? Is she taking the blame for someone else, and if so, why? Why did Blackie remove the murder weapon, and then tell the police about it? With few clues with which to begin his investigation, Blackie soon finds himself confronted with certain difficult questions he must find answers to before he can hope to uncover the motive, and then the perpetrator of this strange and unusual “Hypnotic Murder.”

For some reason I found myself curious about Boston Blackie‘s radio ratings being as solid as they were during a time when the relatively new invention of television might have drawn some listeners away from it and other radio programs, so did some informational digging. When this story took place in 1945 the population of the United States was 140 million. There were estimated to be only 10,000 commercial television sets in the country, and only 0.5% of households a year later in 1946 had a set. Four years later in 1950 there were 6 million tv sets. And today in the United States it is estimated that just over 300 million tv sets exist–one for almost every man, woman, and child in the country. The sharp rise in sets sold after the war ended in 1945 was due to the fact that the government had put a virtual halt to their manufacture during the war (raw materials were needed for the war effort), and this restriction was lifted in late 1945. So sales of the relatively new invention skyrocketed and television was all the rage among those who could afford one.

Play Time: 26:51

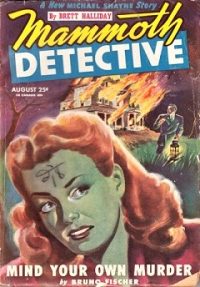

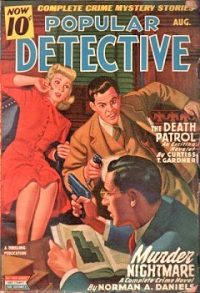

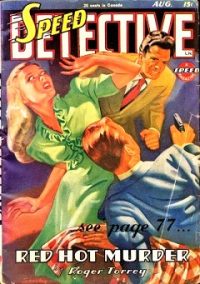

{While the neighborhood gang had finished reading their recent SF pulp magazine purchases and were now in the mood after listening to this episode of Boston Blackie for further dark and dangerous detective stories, little did they realize that after they had returned home from the corner newsstand, had finished their supper and had begun to get a head start on the magazines below before turning in for the night, that nearly half a world away and a few hours in their future the United States would begin to end World War II in the Pacific by bombing the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 with the first atomic bomb deployed in war. But since this event had not yet happened in the world of our innocent neighborhood pulp fictioneers all they were dreaming about were the stories they would be enjoying in the few days to come. Mammoth Detective (1942-47) was a quarterly in 1945, with somewhat fewer pages than its publisher would have wished when he promised over 300 pages per issue, yet its page count was still well above the norm and provided hours of thrilling action for its audience, young and old alike. Popular Detective (1934-53) maintained its loyal readership for 20 years until times and possibly the pulp magazine crash of the early 1950s caught up with it. It was a bi-monthly in 1945. Speed Detective (1934-47) was another long-running detective pulp, though it went through a name change along the way. Originally titled Spicy Detective Stories, it early on offered its thrills and spills laced with a little sex. Time and social pressures finally forced it to tone down or eliminate altogether the latter element by the end of 1942, thus forcing a name change as well. In 1945 the magazine was a bi-monthly.}

[Left: Mammoth Det., Aug. 1945 – Center: Popular Det., Aug. 1945 – Right: Speed Det., Aug. 1945]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.