Tangent Online Presents:

An Interview with Susan Palwick

(This interview was conducted via email from August 31 – September 24, 2013)

Introduction

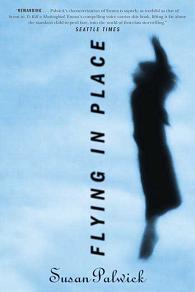

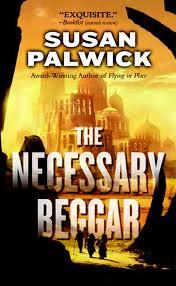

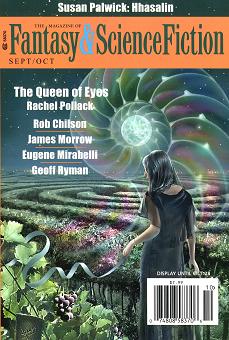

Susan Palwick saw her first published story appear in the May, 1985 issue of Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine. She has written four novels to date: Flying in Place (1992) for which she won the Crawford Award for Best First Novel in 1993; The Necessary Beggar (2005) for which she won the Alex Award; Shelter (2007); and her newest, Mending the Moon, released in 2013. Her first short story collection, The Fate of Mice, was published in 2007. While not prolific, over the years her stories have appeared in a variety of original anthologies and genre magazines. Her latest short fiction, a novelette entitled “Hhasalin,” appears in the September/October issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

Susan attended Princeton and has a doctorate degree from Yale. A practicing Episcopalian and lay preacher, she is an associate professor of English at the University of Nevada, Reno, where she and her husband now reside.

This is an unusual interview for several reasons. It sprang first from nothing more than a stray thought that came to me after reading her story “Hhasalin” in the Sept./Oct. issue of F&SF, and my voicing of that thought in the F&SF Forum where an interesting exchange of comments followed. One thing led to another (as you will soon read) and I decided to ask Susan if she would like to do an interview, to which she agreed. I felt the Forum exchanges – plus those between both of us in private messages on Facebook – were valuable for context and so have included them here as well; and to retain the overall spontaneity and energy of these exchanges, their informality if you will, have elected to portray the entire interview as if Susan and I are doing the interview at a wall table in a convention bar – face to face – spending time before each of us must appear on a panel. I think you will find the result not only different, but unexpectedly candid, revealing, and (on both sides of the virtual microphone) a spirited series of give-and-takes on certain issues that one is not used to seeing in the more “traditional” interview. For this, and for opening up about herself and her work – the passions that fuel it and her life – I wish to thank Susan; it has made for a terrific interview and, I believe, the longest I have ever done at very close to 11,000 words. It is my hope that you enjoy this “raw and uncut director’s version” as much as have I (with Susan’s help) in putting it together.

Tangent: You’ve been writing in the genre for over twenty-five years now, having sold your first story in 1985. While not all of your work has been in the SF/F genre, the majority of it has been. What made you gravitate toward SF/F?

Susan Palwick: I was introduced to SF/F when I was very small, even before I could read, because my older sister read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe to me. My nearsightedness was diagnosed late and I didn’t learn to read until the end of first grade, but then I never stopped. I read everything, but SF/F was consistently my favorite because of the sense of wonder it evoked in me. That’s a clichéd answer, but in my case it was true! Most realistic narratives just felt flat to me. I craved magic and transcendence.

Susan Palwick: I was introduced to SF/F when I was very small, even before I could read, because my older sister read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe to me. My nearsightedness was diagnosed late and I didn’t learn to read until the end of first grade, but then I never stopped. I read everything, but SF/F was consistently my favorite because of the sense of wonder it evoked in me. That’s a clichéd answer, but in my case it was true! Most realistic narratives just felt flat to me. I craved magic and transcendence.

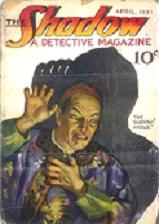

My family encouraged my SF/F habit in various ways – often unknowingly – although they weren’t SF/F readers themselves. My maternal grandfather, Jerome Rozen, and his twin brother George were pulp artists who’d painted some of the first Shadow covers. I was aware of that legacy very early on, and proud of it. To them, the work had just been a job. Jerome wasn’t a fan himself and didn’t understand why people were fascinated by the pulps, but he’d kept some of his old props. I loved exploring his attic, which included one of the original Shadow hats.

My family encouraged my SF/F habit in various ways – often unknowingly – although they weren’t SF/F readers themselves. My maternal grandfather, Jerome Rozen, and his twin brother George were pulp artists who’d painted some of the first Shadow covers. I was aware of that legacy very early on, and proud of it. To them, the work had just been a job. Jerome wasn’t a fan himself and didn’t understand why people were fascinated by the pulps, but he’d kept some of his old props. I loved exploring his attic, which included one of the original Shadow hats.

My parents didn’t like SF/F in general, but they both adored The Once and Future King, so I read that when I was very young. My sister, as I’ve said, introduced me to Lewis, and later to Tolkien, although she wasn’t a fan herself. My father’s second wife wasn’t much of a reader at all, but she knew I was, so every Christmas she gave me a huge box of books, mostly Dell paperbacks but some hardcovers too, and the box always included lots of SF/F because she knew that was what I liked.

My stepmother’s father, who was an extremely difficult person – alcoholic and verbally abusive – spent most of his time watching TV. One day he said to me, “Hey, you like that science fiction stuff. There’s this show you should watch. It’s called Star Trek.” So we watched Star Trek together, which was a safe way of spending time with him.

I was a squirrely kid, neither athletic nor popular, and for a long time my imaginary friends were my main social circle. By third grade, the imaginary friends had morphed into an intricate fantasy world called Aleia (pronounced like “Alien,” but with a final “ah” rather than a final “n”), populated by all the characters I’ve ever loved, plus some I’ve invented, plus Mary Sue versions of me. Elsa, the lioness from Born Free, mated with Aslan and had cubs, for instance. When I found the real world unpleasant, which happened quite a lot – I had no idea how to get along with other children, and I was routinely bullied right up until high school. I zoned out and went to Aleia, which was a lot more fun and interesting.

My most reliable Aleia time was third-grade math class, which I hated. The teacher, a pretty young blonde woman, baffled and intimidated me, and the times tables were torture. So I’d zone out, but whenever I did, she’d say, “Susan, are you daydreaming? Go to the back of the class.” The back of the class were where the dumb kids sat, at a table by themselves. So I’d sit back there and happily have adventures with Spock and Puddleglum and the lion cubs, and also the three princes I’d invented who wore disc-shaped jetpacks on the bottoms of their shoes and zoomed through the sky while they competed with each other for the throne. This was all much more absorbing than times tables.

My math teacher, who didn’t understand why being at the back table wasn’t shaming me into working harder, stopped sending me there. Instead she said, “I want you to go to your other teachers and tell them that you aren’t paying attention in class.” The classrooms were arranged in groups of four joined by bathrooms. I wasn’t about to go tell my other teachers – whom I loved – any such thing, so instead I hid in the bathroom, thinking up adventures for the princes and lion cubs, until it was time to go to the next class.

My math grades were atrocious, of course, and my parents were very worried because I was getting good grades in everything else. What was wrong with me? They took me to psychologists for testing. There was talk of having me switch schools. And finally it occurred to somebody to send me to the guidance counselor at my own school. He was a tall, thin man who looked like David Frost, and he asked me the question that no one else – not even my parents, who loved me – had thought to ask. “Susan, when you aren’t paying attention in class, what are you doing instead?”

“I’m imagining,” I told him.

“What are you imagining?”

So I told him about Aleia, about Spock and Aslan and the lion cubs and the three princes, and he sat and listened, and when I’d finished he smiled at me and said, “This is what we’re going to do. I’m going to get out my typewriter, and you’re going to tell me about Aleia again while I write down what you’ve said, and then you’re going to draw pictures to show me what it all looks like. Okay?”

That sounded like fun. He got an old manual typewriter out of a cabinet and perched on a high stool – I remember thinking he looked like a crane – and used two fingers to peck out the story I told him, which was about the three princes’ latest contest for the throne. Then he gave me a pencil, and I drew the three princes zooming through the air with flames coming out of the bottoms of their shoes. I may also have drawn a lion cub.

I thought he was going to keep the piece of paper and talk to my parents about it. But instead he gave it to me and said, very gently, “Now, Susan, I want you to show this to all of your teachers, and I want you to tell them that when you aren’t paying attention in class, this is what you’re doing instead.”

It had never occurred to me that the stories I told myself about Aleia were unusual, let alone valuable. Didn’t everyone tell stories in their heads? The teachers who already liked me – who knew that I had a good imagination and liked to draw – didn’t seem that impressed, but the math teacher did a complete 180. She started bringing me presents. She tutored me during lunch. My mother got a deck of times-tables flashcards and drilled me on problems every day after school, rewarding me with an M&M when I got one right. I shot to, and then beyond, a grade level in math in a matter of months, and there was no more talk of transferring somewhere else.

Tangent: That was a fascinating story, Susan, and in some respects I think there are many who could readily identify with many – if not most – aspects of it. Obviously your imagination remained active into adulthood. When you began to write and sell professionally, to what themes did your imagination turn? What were you interested in writing about as you matured?

Palwick: Well, I’d say my themes are psychological, political and spiritual; I’ll address each in turn.

I’ve mentioned that my stepmother’s dad was alcoholic; she was too, and so was my father, and so was my mother (although she sobered up in AA when I was a toddler). There were a lot of terrific things about my family when I was growing up, including how much everybody not only tolerated but encouraged my reading, but there was also a lot of dysfunction, culminating in my stepmother physically assaulting me during a bout of DTs when I was nineteen. Before that, it had just been, you know, garden-variety codependence and drama, including my father’s theatrical suicide attempt when I was sixteen (his father had killed himself before I was born, so everyone took this seriously), and terrific overresponsibility on my part. I didn’t and don’t drink, but I inherited the anxiety and depression for which, I think, all that parental drinking was self-medication, at least initially.

I loved all of my parents very much. They’re all dead now, which is why I can talk freely about all this. They were all incredibly smart, generous, hard-working people who were also very strong and lucky and survived things that should have killed them. My father was given six months to live in 1976 but led a very full life until he died in 2009, and my mother was expected to die in 1964 but lived until 2010, and my stepmother beat similar odds to die that same year. All three of them were remarkable, and in many ways truly heroic. But, in the way of such things, they gave me a lot of material. (As a side note, from 2004 to 2012, I spent four hours a week volunteering as a lay chaplain in a local ER. Suicidal alcoholics were my favorite patients. I loved talking to them, and I got pretty fierce with medical staff who said anything insulting about addicts.)

Terri Windling told me once, “Whenever anything bad happens to me, I tell myself, ‘I’m a writer. This is material. I can use this!’” That was my approach all along; starting in my twenties I wrote obsessively, in various forms, about things that had happened at home. I now know that writing is a very effective way of healing from trauma; James Pennebaker at U.T. Austin has done a lot of research in this area, and there’s a field called Narrative Medicine, which I teach at my university, that touches on it too. But for privacy reasons I couldn’t write directly about what had happened to me, at least not for publication, so – both consciously and much less so – I translated it into SF/F. My mother, who read everything I wrote, dubbed one early and unpublishable effort “Children of Alcoholics Conquer the Galaxy.” Kathryn Cramer later invented the term “Adult Children of Science Fiction” to describe the work of several writers, including me and Steve Gould; his first novel, Jumper, was published the same year as my first novel, Flying in Place.

Terri Windling told me once, “Whenever anything bad happens to me, I tell myself, ‘I’m a writer. This is material. I can use this!’” That was my approach all along; starting in my twenties I wrote obsessively, in various forms, about things that had happened at home. I now know that writing is a very effective way of healing from trauma; James Pennebaker at U.T. Austin has done a lot of research in this area, and there’s a field called Narrative Medicine, which I teach at my university, that touches on it too. But for privacy reasons I couldn’t write directly about what had happened to me, at least not for publication, so – both consciously and much less so – I translated it into SF/F. My mother, who read everything I wrote, dubbed one early and unpublishable effort “Children of Alcoholics Conquer the Galaxy.” Kathryn Cramer later invented the term “Adult Children of Science Fiction” to describe the work of several writers, including me and Steve Gould; his first novel, Jumper, was published the same year as my first novel, Flying in Place.

Flying in Place is about child sexual abuse, and it’s not autobiographical. The sexual aspects of the story grew out of my growing feminism: that’s the political strand of my writing. My father read FliP and loved it; he liked it more, in fact, than anything else of mine he read. Until the end of his life, he gave copies of the book to his friends and bragged that his daughter had written it. I always thought that was his way of saying, “I’m not the father in this book!”

It shouldn’t be any surprise, then, that families are a huge element of my work; I sometimes call what I write “domestic fantasy.” But they’re usually families that are somehow struggling with or burdened by secrets. You can see that in all of my novels, especially the first three, and in much of my short fiction. All of this is probably clearest in The Necessary Beggar, about a family dealing not only with a speculative situation but with alcoholism, suicide, and toxic secrecy.

It shouldn’t be any surprise, then, that families are a huge element of my work; I sometimes call what I write “domestic fantasy.” But they’re usually families that are somehow struggling with or burdened by secrets. You can see that in all of my novels, especially the first three, and in much of my short fiction. All of this is probably clearest in The Necessary Beggar, about a family dealing not only with a speculative situation but with alcoholism, suicide, and toxic secrecy.

As reviewers of my story collection The Fate of Mice have pointed out, I also write a lot about death and mortality. I’ve been acutely aware of both as long as I can remember – I was never one of those kids who thought I’d live forever – and I can’t seem to get away from those themes, as hard as I try. In the late 1980s, I went through a period of being especially aware of them; my beloved grandfather Jerome died in July 1987, and my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer four months later, and around the same time, two friends in their twenties killed themselves. I was living in New York City during the height of the AIDS epidemic, and every week seemed to bring the death of someone I knew. During that time, I went through the worst clinical depression of my life – although it wasn’t diagnosed until much later – and writing became my way to affirm life in the midst of all that death. My story “Hhasalin” – is from that period (I started writing it in 1988), and so’s Flying in Place, which I started writing in 1989 and which is very much about survivor’s guilt, among other things.

So that’s all nice and cheery, huh? But much of my fiction also deals with political or social themes: feminism, poverty, war, various forms of social injustice. My father was an attorney and a passionate liberal, and he raised us to be keenly aware of civil-rights issues of all kinds. He was brought up Catholic and fell away from the church as a teenager, becoming what my sister called “a fundamentalist atheist,” but I’ve always thought that’s where his devotion to social justice started. My stepmother, who was a slightly less lapsed Catholic, once told him, “Alan, you’re the best Christian I know.” He helped people whenever he could. One year a few years before he died, I asked him what he wanted for his birthday, and he said, “I’m going to give you $300, and I want you to research good charities and donate the money to a couple of them in my name.” He taught us to love our neighbors, although he wouldn’t have phrased it that way.

So that’s all nice and cheery, huh? But much of my fiction also deals with political or social themes: feminism, poverty, war, various forms of social injustice. My father was an attorney and a passionate liberal, and he raised us to be keenly aware of civil-rights issues of all kinds. He was brought up Catholic and fell away from the church as a teenager, becoming what my sister called “a fundamentalist atheist,” but I’ve always thought that’s where his devotion to social justice started. My stepmother, who was a slightly less lapsed Catholic, once told him, “Alan, you’re the best Christian I know.” He helped people whenever he could. One year a few years before he died, I asked him what he wanted for his birthday, and he said, “I’m going to give you $300, and I want you to research good charities and donate the money to a couple of them in my name.” He taught us to love our neighbors, although he wouldn’t have phrased it that way.

That brings me to the third strand of my work: I write a lot about spiritual and religious themes, to the alarm and discomfort of some of my readers. I was unchurched as a kid, but went through a religious conversion in my early forties (to the alarm and discomfort of many of my friends and family, who started calling me and saying things like, “You used to be smart. What happened?”). I’m Episcopalian and like to call myself a proud member of the Christian Left. My father was horrified when I started going to church, but he wound up being proud of some of the work I did, including volunteer work with homeless families and my work at the hospital. He told me once, “You’re someone who gives Christians a good name,” which is probably the highest compliment I’ve ever gotten.

He also got off a very funny line. When I started preaching a few Sundays a year – after three years of training in homiletics – Dad said, “Well, of course you’re giving sermons now. You already write science fiction!” Theologian Walter Brueggeman has said that “The speech of God is always about an alternative future,” so my father was more right than he knew.

Tangent: So much familial dysfunction and alcoholism, step-parents, it all seems so depressing. It’s a wonder you managed to remain even semi-intact as a functioning human being. That must have been rough.

Palwick: It wasn’t all depressing. There were books. There were cats. There was music. There was travel to places I loved. There was swimming. There was a ton of support from a lot of very wise adults (including a group of my mother’s friends in AA, who were and are my role models). There was a lot of good mixed in with the much-less-good, but even my family’s much-less-good was better than many people’s best. I got an incredible education, mostly on scholarship. It was irreducibly complicated, you know? For many years, whenever anyone said, “What an awful childhood you had!” I’d say, “No, it was wonderful!” and whenever someone said, “What a wonderful childhood you had!” I’d say, “No, it was awful!” It was both. I think most people’s are both.

As for coming out of it well: See above re support. I’ve also paid for the summer houses of any number of therapists and psychiatrists, and I took copious advantage of various self-help groups (Alateen, Al-Anon, Adult Children of Alcoholics). None of us get through anything by ourselves, despite the enduring – and very destructive, IMO – myth of Rugged American Individualism.

Tangent: Why do you believe “Rugged American Individualism” is destructive? I’ve never interpreted that ethic to mean “every man for himself, no matter what.” We all need help from time to time, in various ways, and for different reasons. We get help at the local level from our families, our friends, our churches and communities, and there are thousands of government aid programs for innumerable needs, including medical, emotional, educational, and psychological for those who need but cannot afford the help they require. If anything, and over time, the government has discouraged “rugged individualism” in that it has – perhaps with the best of intentions but with unintended consequences – created a dependent underclass; a class of people across all color lines who’ve become accustomed to receiving government aid of one sort or another and because of the way the laws are written have no real incentive to try to get off the government dole. Aid from our government in all of its forms is one of the most generous on the planet and no one begrudges tax payer dollars spent to help the needy; but a lot of the continuing programs are meant to be a helping hand up, not a perpetual, generations-spanning hand out. Is it the very principle of “Rugged American Individualism” that you think destructive, or perhaps the way some have chosen to portray it as an “every man for himself” philosophy? Or something else entirely?

Palwick: Well, first of all, a fairly sizable number of people DO “begrudge tax payer dollars spent to help the needy,” even though many of the needy are children. This is a larger debate I’d rather not tackle right now, partly because it’s fruitless, but let me just say that Rugged American Individualism (henceforth abbreviated as RAI) tempts too many people into a) believing that they have to do everything themselves without accepting help and b) stigmatizing anyone who does need help, including mothers trying to feed their kids on food stamps. Neither attitude is productive or healthy – or kind to self or others, for that matter.

My college students sometimes say things like “I’ve gotten where I am all by myself” or “I do everything for myself,” to which I’m likely to ask a series of questions. “Really? Tell me about that shirt you’re wearing. How did you make it? What did you have for breakfast this morning? Did you grow or raise your own food? How’d you get to school today? If you rode a bike or drove, did you build your own vehicle? Even if you walked, did you pave the sidewalks and roads you traveled? What’s your source of water? Ever attended a public school or used a public library? Ever had to call 911?”

We’re all dependent, and interdependent, on other people, even ones we usually don’t think much about, like road-repair crews. Part of being a responsible human is trying to be thoughtful and ethical about that, as much as possible anyway, which is part of where locavore and fair-trade movements come from. If I don’t make my own shirt, I want to avoid shirts made by child sweatshop labor. If I’m oblivious to the fact that I didn’t make my own shirt but that someone else did, it’s much more difficult to engage with the complexities of the marketplace.

There’s a more immediate and destructive aspect of RAI, though: it isolates people. I live in a state that reliably has one of the highest suicide rates in the country, and it’s not Nevada tourists who fuel that, primarily. It’s people in rural areas who have lots of access to guns and alcohol, not enough access to mental-health services, and an RAI attitude that might keep them from using those services even were they available.

When I was an ER chaplain, I met a lot of patients who wanted to die because they didn’t want to be a burden on anyone else. Part of this was pride and part of it was terror: they couldn’t stand the idea of being dependent on anyone else, even though all of us already are. Some of them had spent years taking care of other people in various ways, and I usually asked, “So how did you feel about being a caretaker? Did you hate it? Did you resent the people you were helping?”

“No! It was a privilege to take care of them!”

“Then please allow the people who love you the privilege of caring for you in turn.”

That seems obvious, but there was an emotional wall: they could acknowledge the idea intellectually, but deep down they didn’t believe it. And that’s not strength. People who are really strong are able to accept help when they need it, and to recognize that help and say “thank you.” My father was a pretty rugged DIY guy – he lived on a seriously fixer-upper sailboat for more than ten years – but when he was dying, he cheerfully and graciously accepted help from me and my husband, not to mention doctors, nurses, and healthcare aides. He was completely matter-of-fact about it and thanked all of us every chance he got. I really admired that.

Tangent: (Chuckling) Spoken as a true Socialist; Obama would be proud would he not? I agree that people who are really in need for whatever reason should not fail to accept the help offered by others out of an undue sense of pride. As for the rest of it, I’m afraid we’ll just have to agree to disagree, but since you’ve indicated that two of your interests, or writing themes, are politics and feminism I felt at least touching on these issues to be appropos. Feel free to respond if you wish.

Speaking of feminism, I attended the first four Wiscons back in the late 1970s, back when they were held in the bitter February cold and the city was buried to its eyeballs in snow. I know you’ve gone there and am interested to know what your experiences have been like up there in Madison. Do you attend regularly, and if so, have you noticed any changes over the years?

Neither of us has a panel for another few hours yet, so I’ll buy the first round while you formulate your response to the above. I know you don’t drink, so what’ll you have?

Palwick: Why, thank you. I’ll stick to water!

I attended WisCon from 2003 to 2008. I had a great time most of those years; I met terrific people and had thought-provoking discussions. The last time I went, I came down with the norovirus that was going the rounds and had one very contentious experience on a panel (which was partly my fault), so the convention wasn’t as much fun as it had been. I haven’t been back since – although I was sorely tempted this year, because Jo Walton was GoH and I love her work – for various reasons that have a lot more to do with finances and family logistics than the con itself.

My sense of the SF/F field in general is that it’s been going through many of the same cultural/political debates, in microcosm, that we’ve seen in society in general: conversations about identity, sexuality, and what constitutes acceptable behavior. I’ve stayed out of all of this – I haven’t belonged to SFWA for decades now, because the infighting’s always made me crazy – and I wasn’t at WisCon during the whole racefail mess, or the sexual-harrassment situation this year. I’ve observed all of that from very far away.

I believe the debates are healthy and necessary, and you can probably guess which sides I’m on in general. I do believe that a few individuals on both sides of various debates have behaved badly, but I agree with SFWA’s recent actions to address toxic behavior from members, and also Tor’s recent actions to address toxic behavior by an editor. I like the person in question and have always gotten along fine with him, but like many others, I knew who was at fault right away, even before he was named, and his behavior wasn’t okay. The woman who went public with her complaint is a friend of mine, and my sympathies are firmly with her here, especially since I’ve seen (and occasionally been subject to) sleazy behavior from guys at cons. I’m glad that conventions are enacting, and enforcing, sexual-harrassment policies.

In general, I’ve been disturbed by the amount of name-calling I’ve seen on both sides of these debates, people using really dehumanizing labels about those with whom they disagree. Even if someone’s behaved terribly, I don’t think insults are okay: they just lower the insulter to the level of the insultee. What we need is respectful conversation. There’s been some of that – thanks to folks who’ve worked very hard to help it happen – but we need more.

I think two factors ramp up the insult index. The first, pretty obviously, is that many of these discussions are taking place online, which makes it much easier to throw around incendiary language; the person you’re insulting isn’t in the same room with you, sharing your oxygen and needing a drink of water and generally being a fellow creature, despite political gulfs. The internet makes everything more abstract, and I suspect it was the direct reason why a lot of the racefail discussions (not all!) got so ugly so quickly.

That leads me to the second factor: the abstraction of the internet and the abstraction of ideology tend to reinforce each other. Ideology makes me really nervous (although, since I’ve self-identified as both a feminist and a Christian, you may be surprised to hear me say so!). When it’s used to analyze patterns of behavior and predict problems, it’s genuinely helpful; when it’s used to dictate behavior or to dismiss entire groups of people who disagree, or even individuals who disagree, it’s dangerous. I believe that lived experience always trumps theory and ideology, but too many people use theory and ideology to dismiss lived experience.

Here’s a personal anecdote from outside SF/F, for whatever it’s worth. When I volunteered at the hospital, I spent one evening helping a guy, about my age, whose elderly mother had had a massive stroke and was on a ventilator in the ER. The doctors weren’t holding out much hope, and he wanted her extubated in the ER, rather than moved up to ICU. That’s not standard practice: ER staff prefer deaths to happen elsewhere.

I talked to the son, talked to the ER doc, and generally did whatever I could to help. This all took several hours, during which I visited other patients, but I checked back periodically. At one point the son broke down and wept in my arms. I prayed with the family and their pastor and was there during the actual extubation (which the patient survived, by the way; she lived another few days).

Over the course of those hours, I forged a real connection to the son. Just before the extubation, I looked at him – he was across the bed from me – and realized that he was wearing a “Hunting Season on Liberals” t-shirt. In other circumstances, I’d have been profoundly offended by that, not to mention threatened. This was, apparently, someone who wanted people like me dead, and thought jokes about killing us were acceptable fashion statements. And under other circumstances, he’d presumably have disliked me as much as I disliked his t-shirt, if he came to know my beliefs.

But under these circumstances, none of that mattered. We had a connection now; politics wasn’t going to break it, or compromise my sympathy for him and his family. And I suspect and hope that if somebody had said to him, “Hey, that chaplain’s a liberal! Here’s a gun so you can take her out!” he’d have refrained. And maybe – just maybe – his opinions about liberals in general would have begun to shift, or at least been a little less black-and-white.

For years I had a bumper sticker on my car that said, “Feminism is the radical notion that women are people.” We’re all people. The more time we can spend working together, side by side in real rooms and real bodies, the better off we’ll be. We need to achieve equal rights and respect and opportunities for everyone, but we also need to honor what we have in common, instead of demonizing each other. That sounds too simple, I know, and I have no idea how to put it into practice. But I do know that in many cases, the internet isn’t helping.

Tangent: I agree with you on the stridency of political discourse and that the abstract nature of the internet is a major contributing factor, in and out of the SF/F community, especially, as you note “when it’s used to dictate behavior or to dismiss entire groups of people who disagree, or even individuals who disagree, it’s dangerous.” And the man you were consoling with that utterly offensive t-shirt goes beyond the pale in my book. And like you, I left SFWA more than a decade ago, the primary reason being the hateful discourse in many of the private SFWA-only forums. It was much too easy to see yourself turning into those types of people whose uncivilized behavior you despised, and I saw it happening in others as well as myself. There were a lot of wonderful people in SFWA, but unfortunately it takes only a few to ruin the overall experience and tip the risk/reward ratio in the wrong direction.

It’s obvious that, like many another writer, you put much of yourself and your life experiences into your stories. In the 1997 anthology The Horns of Elfland: Original Tales of Music and Magic (eds. Ellen Kushner, Delia Sherman & Donald G. Keller, Roc, pb) I can see some of your hospital experiences and the story you related earlier about daydreaming in math class appearing in your story “Aïda in the Park.” At one point you have the main pov character Mary thinking, “Her mother was an extremely practical woman, much like the Mathematical Master in the story, who did not approve of children dreaming.” And the story, of course, is about a young would-be opera singer dying of AIDS. As usual of the stories I’ve read of yours, it packed quite an emotional wollop. While rather a depressing tale, you managed to find something uplifting at the end when, after Danny dies, Mary thinks, “Shivering despite the heat, she wrapped herself in a quilt, and wept, and promised herself and him that she would live.” How hard was that story for you to write? Was the character of Danny taken from someone you happened to know?

Palwick: I wrote that story in ’94 or ’95, a decade before I started volunteering at the hospital or had any idea that I ever would. The line about the Mathematical Master is from Oscar Wilde’s “The Little Prince;” I hadn’t realized until now that it resonates with my own history. Some of the life experiences we writers put into our stories aren’t things we’re aware of at the time!

As for Danny, he was a combination of several people I knew, although he was also heavily fictionalized. I’d spent a few years in the 1980s working in the word processing department of a large company. Nearly all of us there had taken the job to make money while we tried to break into the arts: I wanted to write, and there was a painter and several opera singers. Many of my co-workers were young gay men who wound up dying of AIDS. My boss at that job was also a gay man, older than the rest of us; his partner died of AIDS too, and then he was diagnosed. He’d always been very supportive of my writing – and of the artistic efforts of everyone else in the department – although not exactly in the way Danny is in the story. (My father’s the person who told me that if I wanted to write, I had to try to make a go of it, because otherwise I’d never know if I could have succeeded.) I sold my first story while I was working there, and I remember going to work and telling him, and how happy he was for me. We stayed friends through my next two jobs, and when I decided to go back to graduate school in 1990, he helped me review my French so I could pass the language exam.

As for Danny, he was a combination of several people I knew, although he was also heavily fictionalized. I’d spent a few years in the 1980s working in the word processing department of a large company. Nearly all of us there had taken the job to make money while we tried to break into the arts: I wanted to write, and there was a painter and several opera singers. Many of my co-workers were young gay men who wound up dying of AIDS. My boss at that job was also a gay man, older than the rest of us; his partner died of AIDS too, and then he was diagnosed. He’d always been very supportive of my writing – and of the artistic efforts of everyone else in the department – although not exactly in the way Danny is in the story. (My father’s the person who told me that if I wanted to write, I had to try to make a go of it, because otherwise I’d never know if I could have succeeded.) I sold my first story while I was working there, and I remember going to work and telling him, and how happy he was for me. We stayed friends through my next two jobs, and when I decided to go back to graduate school in 1990, he helped me review my French so I could pass the language exam.

By the time Ellen and Delia and Don asked me to write a story for them for The Horns of Elfland, my friend had left the company on permanent disability and was essentially homebound. When I wrote the story, everyone thought he’d die within five years or so. I wrote it to thank him for how much he’d helped me; it was a hard, sad story to write, but I felt that I had to write it. I dedicated it to him, and he was really pleased.

But the real ending was happier than any of us could have imagined. He was one of the first patients for whom, thanks to the new drug cocktails, AIDS became a somewhat manageable (although still devastating) chronic illness rather than an automatic death sentence. He’s still alive. I talked to him on the phone just last week. I send him all my books. I call him on his birthday every year, and he sends me a card every year on my birthday; he tries to keep his phone bill down because he’s on a fixed income with ever-spiralling medication costs. His main concern these days is how he’ll keep his apartment if his landlords raise the rent. His doctors now say that AIDS probably won’t kill him: the side effects of the medications will.

Tangent: That’s a wonderful, real-life friendship story, Susan; thank you for sharing it. And for those who haven’t read “Aïda in the Park” I strongly urge that you do so if you can find a copy of the book.

With your short story “Wood and Water” (F&SF, September 2000), you rewrite the Cinderella story, giving it a much darker tone than even that of the original we’ve come to know in popular culture, mostly through the Disney animated film. Actually, it’s a continuation of the Cinderella story in that it takes place many years after the original tale. It deals with mother and stepmother issues, hate and love, and self-reliance. Do you think you were working out some of the issues you faced as a child through this fairy tale, either subconsciously or otherwise? What were you trying to say with this piece? I found it rather intriguing, especially so given its short 11-page length. The mother badmouths her daughters, the daughters are skeptical of the trip to meet the “witch” their mother is forcing them to take – but the mother knows things the girls do not, which you help fill in with her back story. And the ending is, again, despite the rather gloomy atmosphere, somewhat uplifting and promises hope for the future. Do we see a pattern emerging in this story, in “Aïda in the Park,” and in your newest short story we’ll get to in a bit, “Hhasalin”?

With your short story “Wood and Water” (F&SF, September 2000), you rewrite the Cinderella story, giving it a much darker tone than even that of the original we’ve come to know in popular culture, mostly through the Disney animated film. Actually, it’s a continuation of the Cinderella story in that it takes place many years after the original tale. It deals with mother and stepmother issues, hate and love, and self-reliance. Do you think you were working out some of the issues you faced as a child through this fairy tale, either subconsciously or otherwise? What were you trying to say with this piece? I found it rather intriguing, especially so given its short 11-page length. The mother badmouths her daughters, the daughters are skeptical of the trip to meet the “witch” their mother is forcing them to take – but the mother knows things the girls do not, which you help fill in with her back story. And the ending is, again, despite the rather gloomy atmosphere, somewhat uplifting and promises hope for the future. Do we see a pattern emerging in this story, in “Aïda in the Park,” and in your newest short story we’ll get to in a bit, “Hhasalin”?

Palwick: Well, obviously “Wood and Water” is about freeing yourself from generational cycles, about finding your way to a new story instead of reliving the mistakes of the past. That’s certainly something I’ve thought about in my own life, and I suppose there are some biographical resonances. My sister and I were the biggest reason my mother got sober in 1964, when everyone expected her to die instead, and she raised the two of us on an extremely tight budget when my father’s situation was at its worst (when I was in high school and college). I know that navigating early sobriety as a single mother was sometimes a real challenge for her, although she rose to it beautifully. She was infinitely kinder and more loving than the mother in the story, though (and their marriages were nothing alike!). For that matter, I certainly hope my sister and I were and are nicer than the daughters in the story!

My mother’s own mother died in a car accident when she was twelve, and I suppose that might be echoed in the visit to the mother’s grave in the story, although that’s a traditional part of some Cinderella tales. (So maybe the family history is why that version appealed to me?) My mother often said that I would have liked her mother, an artist who did fantastically delicate, Art Nouveau style pen and ink drawings. I wish I’d known her. I’m sure Mom wished she’d gotten to know us.

Oh, hang on, wait, stuff’s falling into place now: yeah. My grandmother died when my mother was twelve. When my sister was twelve and I was three, my mother (still drinking) went into the state mental hospital, where doctors said she was a hopeless case and might have to be lobotomized (a procedure performed until 1967). Instead, she went to a visiting AA meeting and got sober. But when I was twelve, I was convinced that something horrible was going to happen, that she’d either start drinking again or die somehow. (I told you I was a morbid child!) I was acutely aware of that family history as a kid, and terrified of it, and I suppose that’s one of the things that informed “Wood and Water” so many years later. I hadn’t connected the two until now, and the connection still feels more intellectual than visceral, but it’s interesting.

As for “Aïda” and “Hhasalin” (which is my most recently published story, but which I began writing in 1988, remember), I think “Wood and Water” has less in common with them than with my other fairy-tale revisions, “Ever After” and “The Real Princess.” All three explore issues of female agency and entrapment; all are very dark. “Wood and Water” is, in fact, the happiest of the three. I also see a thematic connection to “Jo’s Hair,” which revises another familiar story about a young woman settling into a very circumscribed existence. “Gestella” may in some sense fall into this category too, since it takes a myth of power – lycanthropy – and turns it on its head.

Tangent: We’ve mentioned “Hhasalin,” your new novelette in the September/October F&SF, and I want to talk about it, but Tor has just published your newest novel Mending the Moon and I’d like to get your thoughts on it as well. While it isn’t science fiction, it does concern a young man who has grown up reading a comic book about his favorite superhero, and who lives more or less through that superhero character, adopting his morals and ethics. The young man loses his mother to a heinous murder, and…I don’t want to give too much away because the book is still quite new, but could you tell us what gave rise to the book?

Palwick: In 2009, Tor called my agent and said they wanted me to write a mainstream novel for them. My agent, who never pressures me, passed along the message: “They came to us, which doesn’t happen in this market. You will get me a proposal in a week.”

So we kicked around some vague ideas, and I got her a proposal in a week, and they accepted it, which meant I had to write the book.

For some time now, I’ve been fascinated by the problem of how to depict small acts of kindness in fiction, especially in the face of much larger acts of evil. I’ve come to believe that when something like 9/11 or the mass-shooting-du-jour tears a huge ragged hole in the fabric of people’s lives, what stitches it up again is tiny, everyday goodness: somebody donating rice to a soup kitchen, giving an elderly neighbor a lift to the grocery store, adopting an abandoned pet. This stuff’s so common and unremarkable that we often don’t notice it, even though it’s all around us. I think all these everyday acts are what hold the world together. When the Big Bad happens we think, “We’ll never do enough Big Good to fix this!” but we don’t have to, not by ourselves. If enough people do little stuff – even if their actions seem unrelated to the Big Bad, not to mention laughably puny next to it – the balance is maintained.

That may sound really hokey, and it’s certainly not empirically provable. It’s a worldview, an article of faith. This is what Judaism calls tikkun olam, “the repair of the world.” The problem with depicting it in art is that it’s very quiet, very difficult to dramatize or make suspenseful or interesting. I mean, superheroes with capes are much more satisfying in a narrative sense. We want to see the Big Bad get whupped by something definitive, a character or cohesive group of characters we can root for.

As I creak my way through middle age – I just turned 53, and may already be facing knee replacement – I’ve also become very interested in the status of older women in fiction. You don’t see enough of them, especially in genre fiction, who are the heroes of their own stories instead of playing supporting characters to their grandchildren.

As we’ve already established, I’m very interested in how grief affects people, and particularly how it complicates existing problems in people’s lives. My father died three months before Tor requested the proposal; my mother died while I was in the middle of the book, so once again I was drawing on personal material. And I’m also very interested in how fandoms – the narratives of popular culture – help people navigate real-world loss and hardship. My definition of scripture-with-a-small-s is any story that helps create and maintain community. That includes all the various holy scriptures, but it certainly also includes Buffy, The Lord of the Rings, Star Trek, and so forth: any beloved story that imparts a sense of shared experience and values.

I’m also very uncomfortable with most conventional murder mysteries, for the reasons given by Melinda in the book: too many of them present a world in which, once the murder’s solved, everything’s okay again. I don’t believe that. I know someone whose son committed a terrible murder: we all knew right away who’d done it, and he’s in prison for life, but nobody’s especially okay. Life changes forever after something like that.

So: throw all of this into a blender, and you get Mending the Moon, a book about five characters – one adolescent male and four middle-aged-to-elderly women – navigating the aftermath of a terrible and senseless murder, one that’s technically “solved” (we know who did it) but not resolved (we don’t know why). All of the characters have pre-existing life issues that become more difficult in the face of loss and grief and anger; all of them are trying to figure out how to move forward; several of them are bound by a shared fascination with a cult comic book about a dweeby guy who helps communities rebuild, one nail and board at a time, after various disasters. The book’s also about how the murder itself becomes a shared narrative, drawing together the survivors of the victim and the family of the murderer. It’s important to me that the murderer’s mother is one of the main POV characters, and that she’s sympathetic. My goal was to show people struggling to be decent in the face of horror, rather than falling back on our kneejerk cultural narratives of noble revenge. I don’t think revenge is noble. I don’t even think it’s healthy.

So: throw all of this into a blender, and you get Mending the Moon, a book about five characters – one adolescent male and four middle-aged-to-elderly women – navigating the aftermath of a terrible and senseless murder, one that’s technically “solved” (we know who did it) but not resolved (we don’t know why). All of the characters have pre-existing life issues that become more difficult in the face of loss and grief and anger; all of them are trying to figure out how to move forward; several of them are bound by a shared fascination with a cult comic book about a dweeby guy who helps communities rebuild, one nail and board at a time, after various disasters. The book’s also about how the murder itself becomes a shared narrative, drawing together the survivors of the victim and the family of the murderer. It’s important to me that the murderer’s mother is one of the main POV characters, and that she’s sympathetic. My goal was to show people struggling to be decent in the face of horror, rather than falling back on our kneejerk cultural narratives of noble revenge. I don’t think revenge is noble. I don’t even think it’s healthy.

Many readers, predictably, have found the book puzzling or offputting. There’s no neat closure. There are no car chases. There are many scenes of characters doing very hard, interior work to try to manage their pain, which notably doesn’t include adrenaline-producing revenge scenarios. The alternating chapters about the comic book and its fandom mystify or confuse some readers; also, all too predictably, certain readers have perceived the book as being “about” only the adolescent male character, whereas in fact it’s equally about the four older women, apparently rendered invisible by age and reader expectation that older women don’t do or feel anything interesting.

This book isn’t like a lot of other books, so there aren’t neat slots for people to put it into. I’m not sure it’s entirely successful, but I’m gratified by the readers – many more than I expected, frankly! – who’ve found it a rewarding and thought-provoking experience.

Tangent: Thank you, Susan. I think if readers are able to put aside the unconscious reading protocols they use in approaching the “usual” mystery or crime novel, the expectations they bring to that sort of novel, and just let the story unfold of its own accord, that they’ll discover a moving story underneath it all. And happy birthday!

“Hhasalin” is your newest piece of short fiction, a novelette in the September/October issue of F&SF. Since many may not have had the chance to read it yet, I’ll word this question very carefully, leaving out key words to avoid spoilers, thus permitting you to say as much about the story’s details as you feel appropriate. At its core, we see that humans have come to, and settled on a planet where the indigenous, very human-like inhabitants are known as the Shapers. Because of a virus for which there seems to be no cure, the Shapers are dying, their ability to create thought objects between their hands severely affected. One little Shaper female is rescued by a human family from an orphanage after her parents have died. She comes to live with the family, including its two young children, a boy and a girl. She is adorable. She loves the wonderful machines the humans can make and is always silently in wonder of them. The way you have made us see this little female Shaper, the wonder, love, and childlike curiosity she has in her heart is more than touching. Anyone who doesn’t fall in love with her must truly have a heart of stone. Would you tell us about “Hhasalin” and what you set out to do in this story?

“Hhasalin” is your newest piece of short fiction, a novelette in the September/October issue of F&SF. Since many may not have had the chance to read it yet, I’ll word this question very carefully, leaving out key words to avoid spoilers, thus permitting you to say as much about the story’s details as you feel appropriate. At its core, we see that humans have come to, and settled on a planet where the indigenous, very human-like inhabitants are known as the Shapers. Because of a virus for which there seems to be no cure, the Shapers are dying, their ability to create thought objects between their hands severely affected. One little Shaper female is rescued by a human family from an orphanage after her parents have died. She comes to live with the family, including its two young children, a boy and a girl. She is adorable. She loves the wonderful machines the humans can make and is always silently in wonder of them. The way you have made us see this little female Shaper, the wonder, love, and childlike curiosity she has in her heart is more than touching. Anyone who doesn’t fall in love with her must truly have a heart of stone. Would you tell us about “Hhasalin” and what you set out to do in this story?

Palwick: Well, first of all, by the end of the story she’s no longer a child, and I hope readers won’t see her that way. She’s full-grown by her own people’s standards, even if their physical stature is less than that of humans. She claims adult power, and exhibits adult behavior, when she focuses on her art at the end of the story. This isn’t a story about an “adorable” child being victimized; it’s about an adult responding to her own mortality, and to the genocide of her people, by creating work that is uniquely hers. I hope the reader will sympathize with all of the Shapers, with the loss of a race and a culture, even if Lhosi’s the focal point of that sympathy. In your post about the story on the F&SF Forum, which was the beginning of my conversation with you, you made much of the fact that Lhosi’s female, but from this larger point of view, she could just as easily be male.

One of the ironies is that the Shapers have been so colonized that their work is inevitably filtered through a human lens. The Shaper artists on display at the museum have used their art to illustrate what the human world looks like through Shaper eyes, and Lhosi’s artistic urge is to make real a Shaper city that’s no city at all, but a fairy tale – cruel, because a lie – told her by her human adoptive mother. All of these artworks are protests, but they’re also necessarily capitulations. Lhosi can’t return to or access her own culture, which has been destroyed. At the same time, she’s too thoroughly assimilated into human culture to hate it completely, because – as she recognizes – that would mean hating herself. This greatly complicates her task of grieving the loss of her people, whom she can ultimately know only by what the humans tell her of them. At the end of the story, though, she explicitly recognizes that her art is a weapon, the only one she has left. She’s begun the very important work of trying to define her own identity, rather than seeing herself through the eyes of her human family.

It’s interesting to me that some readers – including you, Dave! – persist in reading “Hhasalin” as a sentimental domestic story and not, ultimately, as a story about grief and horror. That may be a flaw of my writing; whatever I “meant” when I wrote the story doesn’t matter if I haven’t communicated it to the reader. But this strand of reader response might also be a symptom of the fact that girls and women are still, in the 21st century, all too often infantilized, trivialized, and dismissed. I’ve been on the receiving end of that treatment, both inside and outside SF/F. It’s certainly not universal, and it’s far less common than it used to be (for which we all give thanks!) but there’s still too much of it out there.

Someone recently wrote a blog post on how to talk to little girls. The gist of it was, “Don’t tell them they’re pretty or compliment them on what they’re wearing. Ask them what they’re reading.”

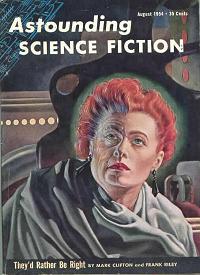

Tangent: Thank you, Susan. I think now would be a good time to allow readers the opportunity to get caught up on our posts in the F&SF Forum now that you’ve mentioned them, in order to better understand and place in context your answer above. I will say beforehand, that the reason I placed an emphasis on Lhosi’s being a young female (and young doesn’t necessarily mean a child or adolescent, as Lhosi is a young adult female at story’s end), had everything to do with a stray thought I had about Tom Godwin’s classic August 1954 Astounding story “The Cold Equations,” which also sported a young female purposely portrayed as sympathetically as possible, and was most assuredly not an objection to your doing so in “Hhasalin.” I make no complaint whatsoever in your portraying Lhosi as a sympathetic character; indeed it made the story all that more effective.

Tangent: Thank you, Susan. I think now would be a good time to allow readers the opportunity to get caught up on our posts in the F&SF Forum now that you’ve mentioned them, in order to better understand and place in context your answer above. I will say beforehand, that the reason I placed an emphasis on Lhosi’s being a young female (and young doesn’t necessarily mean a child or adolescent, as Lhosi is a young adult female at story’s end), had everything to do with a stray thought I had about Tom Godwin’s classic August 1954 Astounding story “The Cold Equations,” which also sported a young female purposely portrayed as sympathetically as possible, and was most assuredly not an objection to your doing so in “Hhasalin.” I make no complaint whatsoever in your portraying Lhosi as a sympathetic character; indeed it made the story all that more effective.

What led to the discussion in the F&SF Forum was that I happened to recall that a few years ago there was a debate concerning the choice of a young female character as the unfortunate stowaway in “The Cold Equations,” and that it was Astounding editor John W. Campbell who had been the driving force behind the author changing the stowaway to a female that some were now arguing was a sexist decision. And because you had so effectively pulled our heartstrings with Lhosi in “Hhasalin” I wondered if those same folks would attribute the same charge of sexism here. The discussion proved interesting enough that you wished to chime in yourself but had trouble logging into the Forum, so Gordon (Van Gelder) posted your responses on your behalf, and to which I replied. Our exchanges follow.

(F&SF Forum exchanges)

Palwick: First, a question. Lhosi wouldn’t be sympathetic if she were male? Why not? (That claim seems to recapitulate Campbell’s vis-a-vis Godwin.) Certainly, a male Lhosi would greatly complicate the parody of postcolonial domesticity in the story – Lhosi’s basically being exploited as a nanny – but why would it make her plight any less poignant?

Next, an observation: “Hhasalin” ends, not with Lhosi being pushed out an airlock, but with her claiming her power as an artist. Bit of a difference, yes?

Thanks for your attention to the story; I’m greatly flattered.

Truesdale: To answer your questions, Yes, Lhosi would be sympathetic if she were male, but not nearly so much. We (I think) still have this special reaction to what amounts to (in a general sense) the harmless, defenseless young female (females in general, but younger especially, I think). Exploited as a nanny? I think “exploited” is the wrong word. Sure, she does her part around the house, but isn’t a lot of it because she wants to fit in and do what she can? “Exploited” connotes something much more negative to me. And yup, I agree with your last point that the story ends with Lhosi deciding not to give up or be pessimistic about her life, but drawing on her inner strength to become the best artist she can be, re Hhasalin. Very nice, really. But the point I was trying to make was the emotional reaction you wanted to wring out of the reader, the sympathy you wanted the reader to feel, in order to make whatever point you eventually wanted to make. It’s not that the stowaway in Godwin’s story and Lhosi in yours ended up dead or alive, but how the emotional strings were pulled in each story to bring about the desired end. And both stories – for whatever reasons and for whatever ends – used a young female. That’s all I was getting at. And then, of course, that Campbell/Godwin was accused of being a sexist, and I believed that you would not be. I don’t think your story is sexist, but for the sake of consistency I was wondering out loud in the Forum if those who claimed “The Cold Equations” was sexist would now say the same about yours. And then one thing led to another, and you know how these things tend to drift…

Regards, Dave

[To which Susan replied to me on Facebook, still unable to get into the Forum (and I’ll save her the trouble of repeating herself here, and then offer my further reply)]:

Palwick: Well, I think she *is* exploited, somewhat, because her relationship with the siblings isn’t that of an equal, but of some combination of pet and servant. The parents make no effort to correct this because they’re too clueless to notice it, for the most part (Jakob receives some superficial scolding, which only backfires). In the final museum scene, for instance, Lhosi clearly feels responsible for watching over the kids. In that sense she’s far more grown up than any of the adults in the story except for the doctor and the museum guard.

Note that her own people would consider her fully grown, although they’re smaller in stature than humans; she’s no longer a child, although she was when she was first adopted.

And I think the gender issue puts us in eye-of-the-beholder territory. I *hope* the story would still affect readers if a young male were the protagonist. (I mean, good heavens, look at Ender’s Game – speaking of political controversy!) In any case, I didn’t – consciously, at any rate – write Lhosi female to play reader sympathy, which of course doesn’t mean that’s not the effect it has anyway! I wanted sympathy for her to arise from her situation, not her gender.

Cheers – and if you’re at Worldcon, have fun!

Susan

To which I replied:

Truesdale: Susan, the issue of Lhosi’s “exploitation” isn’t the issue I was raising. I still disagree that she was being exploited (little Shapers of the World Unite!), but to again repeat my position on this:

For whatever reasons and for whatever purposes, you and Godwin/JWC decided to use a young female to (ahem) exploit the sympathies of the reader. Godwin/JWC were castigated for it and called sexist, and I was just wondering if some of that same vocal crowd would say the same thing about your story. No other issue should distract from this primary focus.

You are a consummate writer, you craft your stories very carefully and with purpose to specific ends. You’re good at it. You’re sensitive to gender issues and even empower the young female, Lhosi, at the end of the story. You’d have to have a heart of stone not to feel for her plight, and then her final determination via her Art. (A one off thought: Are females the only ones needing to be empowered, or do males need to be empowered too?) And yet you claim that you did not “consciously, at any rate – write Lhosi female to play reader sympathy…”. You craft everything else consciously and for a reason…but not the gender of Lhosi? Are not writers, especially those who are known for their carefully crafted tales, in charge of their material? How can everything else in “Hhasalin” be worked so precisely and with conscious effort, but not the gender of the protagonist who you knew you needed to make the reader sympathize with? Or didn’t the gender of your main character matter to you, so you flipped a coin and it came down female? I’m sorry, Susan, this just doesn’t square up for me.

I simply find it difficult to believe that you didn’t have gender on your mind in some form or fashion, when you elected to write Lhosi as female. Is a female character just the default gender for you, so that with all good intentions you didn’t take into account how that choice might come across to a segment of the readership? I just don’t know, really. Please help me to understand why you chose the female gender for your protagonist here, and if it was arbitrary, then why make specific choices in the rest of the story and not with the gender of the protag, given how aware and sensitive you are to gender issues. I ask these questions seriously. But something isn’t squaring up for me.

Anyway, the deed is done and comparisons will be made from the text of both stories. Whether you meant to do it or not, you and Godwin/JWC used the same writerly tool to extract sympathy for a young female character for purposes of your very different stories. The hows and whys will differ, but the fact remains that somehow the dart has fallen twice on the same choice of type of character. And I just found it odd, and interesting.

Thanks for taking the time to answer my questions and for joining us here.

(End of F&SF Forum exchanges between Susan and I. I then emailed her privately and asked if she would like to do this interview. She readily agreed and here we are.)

Please feel free to respond, or to add anything else to your thoughts on “Hhasalin,” whether they have anything to do with my speculation or not. The floor is yours, but our respective panels will be starting shortly.

Palwick: I think the “Hhasalin”/”Cold Equations” parallel is loose at best: for one thing, the issue with Godwin’s story is that his editor asked him to change the gender of a character – a bit of gender politics that doesn’t apply to my story – and anyway, I’m hardly the only writer since then to have written a sympathetic female character, young or otherwise. I’ve written stories that began, and continued, explicitly as responses to gender issues or tropes – “Ever After” and “Gestella” are the two best known in that category, and my Tor.com story “Homecoming” is the most recent – but this isn’t one of them. That of course doesn’t mean that there isn’t subtext there for other people to discover.

Truesdale: You’re missing the point I was making about both of you deciding – for whatever reason – to make your characters highly sympathetic female characters. You both sought to elicit sympathy for your characters. This isn’t a bad thing by any means. I’m not contesting that at all. What drew my attention was that when Godwin did it he was accused of being sexist, and I seriously doubted if you would be by some of the same people if they were to read your story. It’s the double standard I was wondering about, and questioning, not what you or Godwin did.

Palwick: Many writers have chosen to create sympathetic female characters. In fact, as long as there have been writers, some of them have been creating sympathetic female characters. Because I see very few similarities between my story and Godwin’s – other than having a sympathetic female character, which both also share with “Rachel in Love,” “King Lear,” and Middlemarch – I’m somewhat stumped as to how to respond. No, I don’t believe that readers who find Godwin’s story sexist would believe that mine is, but I don’t think that’s a symptom of a double standard. I think it’s because the stories are in fact much more different than they are similar. Godwin’s is about the knowing and deliberate death of one female character to save a bunch of men; mine’s about the inadvertent (but no less devastating or criminal) genocide of an entire culture. Godwin wants us to believe the young woman’s death is absolutely necessary; one of the points of my story is that all those deaths (including potentially Lhosi’s, although neither we nor she know how long she has) were engineered by humans invading a place where they had no difference being anyway, and were therefore completely preventable. Lhosi’s race winds up dying for having committed the sin of self-defense against a conquering force; the young woman in Godwin’s story dies because she’s too naive to follow instructions, and no one else has the will or imagination to figure out another way around the problem.

They’re not the same story.

Truesdale: I realize they’re not the same story. It doesn’t matter that they’re not the same story. What matters is that both stories used female characters to elicit a certain sympathetic response from readers toward their own ends. The sympathetic aspect in one story was called out as being sexist, and I was wondering if yours would be as well, if the people who objected to the sympathetic female in Godwin’s story were to apply the same criteria to yours, would they cry sexist as well. And I doubt that they would. But I see we’re sort of at an impasse here, and it’s getting close to time for our panels. So I want to thank you, Susan, for taking the time for this interview, and for being so open and willing to discuss yourself and your work.

Palwick: Thank you for being so willing to listen to me and to argue with me! I’ve enjoyed our conversation immensely. By the way, were I writing “Hhasalin” from scratch now, I’d probably make Lhosi gender-neutral, and maybe I should have done that when I revised my draft from 1988. The pronouns seem to be distracting at least some readers from what I see as the central issues (although I’d argue that this proves we still need feminism). But I like the story as it stands, and now it’s allowed me to have a lively dialog. Don’t you love that about SF/F?

(At this point someone wearing a convention committee badge walks into the bar, spots us, and walks over. She informs me that my panel on Conservative Politics in SF has been cancelled due to lack of interest, and that Susan’s panel on Liberal Politics in SF is packed to overflowing and they’ve had to open the room divider between my cancelled panel and hers to accommodate the overflow. I wish Susan well and begin staring into my half-finished beer when a couple of five-dollar bills lands next to my glass. “Here you go,” she says with a twinkle in her eye and a slight smile on her lips. “My treat.” I thank her again, order a pitcher of beer with the five-spots, and sit back to wait for my fellow panelists to come dragging into the bar. A pitcher of beer in trade for a cancelled panel? Not a bad deal these days.)