Tangent Online Presents:

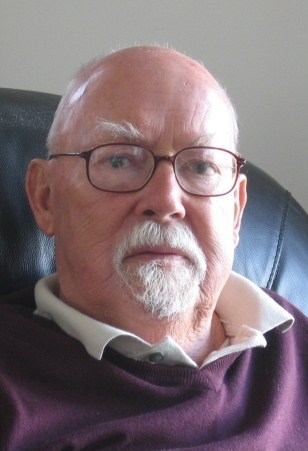

An Interview with Harry Harrison

(1925-2012)

(Photo by Paul Tomlinson–2006)

Interviewers:

Dave Truesdale & Paul McGuire III

Location:

Minicon 10, Minneapolis, MN

Date:

April 20, 1975

Harry Harrison interview first appeared in Tangent #3, September 1975 and is reprinted here for the first time.

(Front and rear cover art by Mark Gruenwald.)

Introduction

Aside from a Star Trek convention the summer of 1974 in Detroit (where rumor had it that Harlan Ellison and David Gerrold were to appear–a false rumor it turned out–but is why I went), Minicon 10 in April of 1975 was my first “real” science fiction convention. Only twenty-four and filled with the excitement a new adventure brings, I and two friends drove from Oshkosh, WI to Minneapolis for the event. I would interview easily a half dozen Big Name authors that weekend, would party till the cows came home, and return to Oshkosh exhausted, yet still riding an energy high that lasted for weeks. We talked about who we’d met, the parties we attended, and those we’d interviewed for months.

Harry Harrison was the first author we actually met that wild weekend, and it was purely by accident (or lucky happenstance). My friends and I were sitting in a crowded hotel bar that also served light food (sandwiches and such), just within earshot of the ballroom where opening ceremonies would shortly begin. The doors to the ballroom were open so we were able to hear when the Toastmaster would call the packed crowd to order. So far, so good. Nothing was happening yet as we were into our 2nd or 3rd pitcher of beer and snacks.

Then this guy walks in and can’t find a place to sit. He scans the room and sees the only available spot is at our table. He walks over smiling and asks if he could join us. His nametag read “Harry Harrison.” Amidst a quick shuffling of bodies and scraping of chairs, we stole looks at one another. Harry Harrison! We were pretty much dumb-founded and didn’t know what to say. Harry filled the void by immediately ordering two pitchers of beer and a sandwich, then asked if we were enjoying the convention. We fessed up and told him this was our first, where we were from, and that we’d just gotten in and had been told that if we wanted to meet SF authors the best place was in the bar.

Long story short was that as Harry wolfed down his sandwich and began working seriously on the beer, we had the most delightful conversation…or rather we mostly listened to Harry. Boisterous, funny, energetic, and completely at home, he regaled us with story after story for a good forty-five minutes or more. He also bought a couple more pitchers of beer for the table–an offer we couldn’t refuse. After all these years I remember only a couple of snippets of those stories. Something about the joys of eating deep-fried caterpillars in Mexico, and how he almost (many years previous), almost hustled the wrong girl the night before. The night before what I have no idea.

We’re sitting there listening to Harry and drinking way too much beer for an afternoon (not knowing all the drinking and carousing that went on evenings at a convention), when opening ceremonies began and the Toastmaster began introducing the various Guests, in alphabetical order. We looked at Harry and told him he’d better get in there for his name would be announced soon. He waved it off and said he had time, it was no big deal. More beer was drunk and time passed. All of a sudden Harry’s name was announced, it was obvious to the crowd in the ballroom that Harry wasn’t there, and then several fans at once shouted the default phrase when someone is absent at opening ceremonies, “He’s in the bar!” Which in this case was actually true. So what does Harry do? He takes what is left from one pitcher of beer and tops off all of our glasses, then sitting at the table (not standing up), takes the other full pitcher and proceeds to chug it without stopping to take a breath. Straight down. He then stands up, belches politely, thanks us profusely for our company, and heads for the ballroom. I remember we laughed for a long time as we sat there looking at the empty chair and pitcher, and with our expressions were asking each other, “What just happened to us? We just sat and talked and drank with Harry Harrison and the convention hasn‘t even started yet!”

Before Harry left us he agreed to an interview, which you see below. Actually, it is one of two we did with Harry. Two days following the convention Harry gave a lecture in Fon du Lac, WI., where he spoke exclusively on the film Soylent Green. Since a (then) recent issue of the now long defunct (defunct at the time of the publication of our interview, in fact) Vertex had covered some of the same material as the Fon du Lac speech, I decided not to be redundant and never published that second interview/taped speech. I wish I had and maybe will some day.

Harry was always joking around, laughing, telling bawdy jokes, and never seemed to run out of energy. Near the end of my time as editor of the SFWA Bulletin (late 2001 or early 2002) I asked Harry if he would contribute an article. He replied asking if he could begin a series of pieces looking back on various aspects of SF as he saw them–an informal autobiographical series as it were. I of course said yes. The first piece appeared and I was looking eagerly forward to more. Then Harry’s wife Joan passed away in 2002 and I didn’t press Harry for his next piece, feeling he needed some time and realizing there were more important things than a Bulletin deadline. I left the Bulletin before I could get back with Harry and that single column was the last.

Harry was always joking around, laughing, telling bawdy jokes, and never seemed to run out of energy. Near the end of my time as editor of the SFWA Bulletin (late 2001 or early 2002) I asked Harry if he would contribute an article. He replied asking if he could begin a series of pieces looking back on various aspects of SF as he saw them–an informal autobiographical series as it were. I of course said yes. The first piece appeared and I was looking eagerly forward to more. Then Harry’s wife Joan passed away in 2002 and I didn’t press Harry for his next piece, feeling he needed some time and realizing there were more important things than a Bulletin deadline. I left the Bulletin before I could get back with Harry and that single column was the last.

Harry wrote or edited far too many books to list here, but for those interested his Wikipedia page provides an extensive listing. Some of his most popular novels include the Bill, the Galactic Hero series, the Stainless Steel Rat series, the Deathworld series, the Wheelworld series, and the Eden series. Two of his most popular stand alone novels are Make Room! Make Room! and the outrageously satirical (which many of his books are) The Technicolor Time Machine.

Harry was honored with the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award in 2009.

After a long night of partying and far too much drinking, where we saw Harry at many parties, drink in hand, and we weren’t in the best of shape for much of anything except sleep, we began our interview early the next day with…

TANGENT: How do you feel this morning?

TANGENT: How do you feel this morning?

HARRY HARRISON: Oh, shit. Is this thing on? (Laughter)

TANGENT: Okay, then… What differences, if any, exist between European science fiction and American science fiction?

HARRISON: The differences are just coming about now. European science fiction, up until about a year or two ago, was American/British science fiction. They never had any other kind. The French and British science fiction was many times written under American pen names. You know, like Robert Rainbell or Joe Duluth or something. Or William Morris or some goddamn thing. But I would say within the last year or two, with fanac and conventions and things just breaking through–but still, they were buying American science fiction. Like only about five years ago the first Dutch science fiction came out. You know, they translated. My agent sold some there. He said, you know, we’ll try it out there. 5,000, 8,000, 10,000 copies–we sold it all. Which tells us two things: a) SF sells, and b) by Harrison and Aldiss. (Laughs) But all this has come about recently. You know, they had no science fiction. First they get Clarke and Asimov, and they think Wow! And then after a couple of years they realized there were a couple of locals, and these guys were just dying to sell something and they couldn’t. They were fan writers, or writers who were SF fans. They started writing their own stuff after three or four years. Most of what they write now is pretty good, but there’s so damn little of it.

TANGENT: What there is though, is pretty good?

HARRISON: Fairly good. But the Russians, they’re off by themselves most of the time. That’s a separate corner. The Russians, I’d say, are twenty-five years behind. What’s this, 1975? The Russians are at 1950 when it comes to science fiction. Up until now, it was all Gernsback science fiction. (Laughs)

TANGENT: Are there any plans for more science fiction getting published in Europe?

HARRISON: Well, I make about half as much money in Europe as I do in the States. The big ones are always Japan and Germany. They even pay royalties, too.

TANGENT: What about Sweden?

HARRISON: It’s been about only four or five years for them, too. First it was one or two books; now they have a whole Swedish fandom. Sam Lundwall was the first guy there. He was Mr. Science Fiction there for a long time. After him there were a number of guys. They had fandom there, but no books.

There’s a British con coming up in Easter. They’re really into it. When you go to a con in London it’s only about half English people there. There are about 4 or 5 or 6 Americans, there are a dozen Germans, a lot of Swedes coming in, 5 or 6 Frenchmen, the Belgians are very big… There’s a big con coming up in Luxembourg in July, they’re really hot there. And the Dutch are coming around, and the Italians are coming around. There’s a little fandom there.

TANGENT: Do they teach science fiction in the classroom in Europe?

HARRISON: They haven’t gotten to that yet. They have some guys doing courses in some high schools; one here, one there. In the universities they have only two courses. One is at St. John’s College-Oxford; they have a science fiction course there. The professor is a Chaucer specialist. (Laughs) Chaucer and SF? They can’t put him down now can they? (Laughs) They have some big organizations there, though. Lots of fanac.

TANGENT: Lots of people are concerned with science fiction becoming respectable and others say who cares, what difference does it make? What is your opinion on this?

HARRISON: Science fiction is so big now–big in sales, big in acceptance. We have better science fiction in one stream and more intellectual science fiction in the other stream. It’s getting harder to tell them apart. It’s pretty easy to see what’s on the bottom: Star Trek, Perry Rhodan, and Burroughs, that’s where you start. It’s good kid stuff. Some stay into that for their entire lives; look at Sam Moskowitz. I have nothing against Trekkies, you know; when they grow up they’ll read science fiction. It’s opened up a whole new field of readers. There’s a whole lot of ridiculous in-fighting too. Trekkies can’t stand Burroughs, and Burroughs fans can’t stand all the intellectual crap. But there’s room for it all in science fiction.

HARRISON: Science fiction is so big now–big in sales, big in acceptance. We have better science fiction in one stream and more intellectual science fiction in the other stream. It’s getting harder to tell them apart. It’s pretty easy to see what’s on the bottom: Star Trek, Perry Rhodan, and Burroughs, that’s where you start. It’s good kid stuff. Some stay into that for their entire lives; look at Sam Moskowitz. I have nothing against Trekkies, you know; when they grow up they’ll read science fiction. It’s opened up a whole new field of readers. There’s a whole lot of ridiculous in-fighting too. Trekkies can’t stand Burroughs, and Burroughs fans can’t stand all the intellectual crap. But there’s room for it all in science fiction.

There’s even room for academia. They may ruin a few authors, those who write books for academia to read–and you know who they are–but alright, let them write for academia if they want to. Academia’s pretty stupid most of the time anyway. The academic journals are really pretty crummy, but, eh, let them enjoy themselves, it’s the commercial field of publishing, too.

TANGENT: Is there any kind of science fiction you just won’t publish because of the type it is? Like the people who take themselves too importantly, for instance?

HARRISON: No, not at all. I won’t publish bad stories. But I publish “New Wave,” anything at all. I published Ellison. I don’t like too indulgent type stuff. I don’t like it when it’s too dirty mouthed for no reason. If you need profanity and sex it has to be part of the story. If it’s publishable, I’ll print it.

I got this story one time that was really good, but it had these profane words in it that just didn’t fit. They just glared and were awful but the story was good. So I wrote the author and said I liked the story but did it have to have all those four-letter words in there? He wrote back and said Whew!, he would be glad to take the profanity out, he just put them in there to please the people at Clarion. (Laughter) He didn’t want them there, either.

But anyway, if a story is good I’ll print it, that’s about what it amounts to.

TANGENT: What market do you aim for in your anthologies?

HARRISON: I aim for the readers. I’m more catholic in my editing tastes that I am in my writing taste. When I do an anthology all I ask is that it be an entertainment. It must captivate me, charm me in some way. It must give me something; humor, plot, pathos, love, action, a jazzy idea–stir my brain cells. If a story does this I’ll print it, that’s all. And I don’t worry about the fan press, trying to get them on my side–it’s not everything. There are maybe 20 or 30,000 hardcore science fiction fans, and maybe 2 or 3,000 who do the fanac. Okay, but besides this there are maybe 3 or 400,000 readers who buy science fiction who’ve never heard of fandom, never heard of the magazines, who just buy science fiction like anyone else would buy a detective or a western.

TANGENT: What about some people in fandom who have a big voice, though. Couldn’t they use it–in whatever degree–to sell their books?

HARRISON: You can use fandom to sell extra copies of books. If you want to work very, very hard–like somebody’s name I won’t mention, a big, tall guy who goes around with a big mouth–you can do this, you can use fandom and get awards and prizes and get maybe more sales that way. But why do it, you know? They like your stuff or they don’t like your stuff. To utilize fandom is kind of a shady thing to do. You’re exploiting it. I enjoy fandom for pleasure. I like cons and talking to fans. If they want me to get up and talk or be on a panel or something, I’m more than delighted.

Fandom is supposed to be for fun, right? That’s what it’s all about, right?

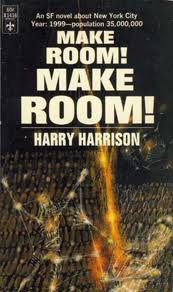

TANGENT: What kind of research did you do those six years you were writing Make Room! Make Room!?

TANGENT: What kind of research did you do those six years you were writing Make Room! Make Room!?

HARRISON: At that time there were no books about pollution or population. There were no books. I had to go to the library and dig around, to my book agent to get him to find books on population, on agronomy, on petroleum research and so on, to try to get every single facet of the world and try to put it all together, and make a close picture of say thirty years ahead. I got everyone’s prediction of what it was going to be like and compared them. You can’t get a one-to-one ratio every time.

Our petroleum consumption was easy; you have this graph that goes like this–here’s production and here’s consumption and here they cross. Easy. Discovered wells, hopefully discovered wells, and it runs pretty easy. You know just about what they’re going to find. But with agronomy it’s more complicated. Utilization of land, new grain coming along; you have to put all this shit together, and finally I came up with the worst possible picture of the world I could. That’s what you do, you know. But the question was, in practical terms, how would we be living some thirty years from now? What would people have, what wouldn’t they have, and if they didn’t have this or that, then what would they have instead. And then I took six years–while working on other things of course–and plotted it all out. I made that world as complete as I could. I had to make it all come together. And then came the art. I had to make a story of it. I outline everything in detail, sometimes ten, fifteen page outlines. I don’t always follow it exactly, but I have to know where I’m going before I start.

TANGENT: Who first picked up on Make Room! Make Room!? Who first noticed it?

HARRISON: Nobody. No one at all. Just the producer and Charlton Heston who read it and liked it. But otherwise the book just sailed by.

TANGENT: What are you working on now? Anything in the works?

HARRISON: Yeah. I’m in the middle of a book I think will be called Wheelworld. I hope to finish it this month. Bobbs-Merrill is doing this one. I got the mad idea for this book while I was driving on the freeway. All those cars and trucks rushing by–all the wheels. You know, what if the entire world drove around in 40-ton trucks all day! My god! (Laughs) So my problem was to justify this. So you have a really hot world with a big axial tilt, with a big oblate orbit. There are two continents and they have terraforming you know, but instead of a mountain chain in between them they have a road between them, on this farming world. They have a big empire, and what they do–I think they have a four- or five-year cycle–is for a year or two they’re in there farming like crazy, putting all this stuff in granaries, and then the ships come and take it away to the other continent. By now, they’re in a kind of twilight zone, just a touch of twilight, say 85 or 100 degrees. Direct sunlight is 186 degrees or something, you know. And before too long they kill all these cows, a few calves or something, take a sperm bank, take the seed corn, and they live in trailers, big atomic trucks–(laughing)–and they’ve got a 40-foot wide road, 12,000 miles long, and they take off in these trucks and away they go, VROOOMMM, VROOOMMM, before the new weather gets them. Wow! Every American’s dream. Sitting behind this big machine with the wheel over their heads!

HARRISON: Yeah. I’m in the middle of a book I think will be called Wheelworld. I hope to finish it this month. Bobbs-Merrill is doing this one. I got the mad idea for this book while I was driving on the freeway. All those cars and trucks rushing by–all the wheels. You know, what if the entire world drove around in 40-ton trucks all day! My god! (Laughs) So my problem was to justify this. So you have a really hot world with a big axial tilt, with a big oblate orbit. There are two continents and they have terraforming you know, but instead of a mountain chain in between them they have a road between them, on this farming world. They have a big empire, and what they do–I think they have a four- or five-year cycle–is for a year or two they’re in there farming like crazy, putting all this stuff in granaries, and then the ships come and take it away to the other continent. By now, they’re in a kind of twilight zone, just a touch of twilight, say 85 or 100 degrees. Direct sunlight is 186 degrees or something, you know. And before too long they kill all these cows, a few calves or something, take a sperm bank, take the seed corn, and they live in trailers, big atomic trucks–(laughing)–and they’ve got a 40-foot wide road, 12,000 miles long, and they take off in these trucks and away they go, VROOOMMM, VROOOMMM, before the new weather gets them. Wow! Every American’s dream. Sitting behind this big machine with the wheel over their heads!

TANGENT: Just think, you may open up a whole new audience of truckers, too!

HARRISON: (Laughing) Right, right! Oh, ahh! (Wiping tears of laughter)

TANGENT: Jim Baen thinks it’s time we got away from stories that say “If this goes on…” and start looking for solutions to all the terrible things that might happen to us. He wants more upbeat stories now. What do you think?

HARRISON: (Chuckling) He can say whatever he wants, science fiction goes on its own way. There is no goddamn “science fiction”; there are a lot of individual science fiction authors that’s all, doing their own schtick.

TANGENT: But don’t you think there have been a lot of stories lately in the vein of “If this goes on…”?

HARRISON: Far too many. In a way I started the whole damn thing with Make Room! Make Room! in the middle 60s, about how terrible it’s going to be. That’s the function of science fiction, to show you how horrible it’s going to be.

There’s always going to be relevancy stories, adventure stories, and all kinds of stories in science fiction, but when someone breaks new ground others won’t necessarily imitate them but they’ll say, Hey, I know something I can do on that. So, there’s an awful lot of room in science fiction for everything. Why not suffer them all? I love’em all. There’s absolutely no hatred left in my bones for anyone.

TANGENT: One more question. Is there any way to save the pulps?

HARRISON: They’re dead. Let’s forget about them. They’re gone. And I don’t want to save them particularly.

TANGENT: Why? Isn’t that a market for new writers also?

HARRISON: An underpaid market. A filthy underpaid market. And they’re going down the drain one by one because the pulp era is over. Now we’re in the paperback era. That’s where the action is, and in original anthologies, too. The original anthology buys new stories for higher prices, it’s as simple as that. Paperbacks and hardcovers pay more.

TANGENT: Isn’t that a more remote set-up for, say, unpublished writers? It’s very easy to get the address of the pulps and send them a story.

HARRISON: That’s just the name of the game. It’s all over for the pulps. Whether you like it or not the world changes. The pulps are going one by one, and each time one goes there’s not another to take its place. The last one to start was Vertex, and I see they’ve just changed their format. If that format doesn’t go they’ll be dead. All the magazines are losing money, with the exception of Analog, because it hits two different readers. It makes more each year. It hits the engineers and technicians as well as science fiction readers.

HARRISON: That’s just the name of the game. It’s all over for the pulps. Whether you like it or not the world changes. The pulps are going one by one, and each time one goes there’s not another to take its place. The last one to start was Vertex, and I see they’ve just changed their format. If that format doesn’t go they’ll be dead. All the magazines are losing money, with the exception of Analog, because it hits two different readers. It makes more each year. It hits the engineers and technicians as well as science fiction readers.

TANGENT: But it seems they publish less and less fiction each month, and more science articles and the like.

HARRISON: That’s their formula, and that’s why they sell about 130,000 copies. They know what they’re doing, you know. John was doing it and now Ben’s doing it; he’s getting the readers and he’s getting the technicians. They sell about 5 or 600 copies at MIT in one day.

Fantastic and Amazing are miserable little things. They’d go broke in a minute if they weren’t underpaying the staff and writers. How many editors do you know who are living on food stamps? F&SF has always lost money in the last ten years, but they make it back by putting out their annual anthology. That keeps them in the black, otherwise they’d go bankrupt. They’re all tottering on the edge, all for different complicated reasons.

TANGENT: Do you think the move to the original anthology is going to produce a better quality science fiction?

HARRISON: I think it is. First of all, you have more editors involved. Instead of three or four editors, you have ten, twelve, fifteen, or twenty, all with completely different tastes. You can be freer in a book, you can have a much wider market. Also, you have no taboos in books.

TANGENT: Why did something like Delany’s Quark series fold after only four issues then?

HARRISON: You’re asking for a personal reaction here, so I’ll give it to you, but I’m saying right now that that’s what it is: a personal reaction. Firstly, his publisher was second rate–very bad. That’s fact. Here’s my theory: as a friend I love Chip, but as an editor I think he’s lousy. I think the contents were miserable. I don’t think there was anything worth reading in there. I think you can fool the readers only so much. I don’t like that one whiney reed of avante garde stuff. If he likes it fine. Did you enjoy reading it?

TANGENT: (Truesdale) To tell you the truth, only one or two of the stories out of all four books I enjoyed. I couldn’t make heads or tails out of most of it. One particular short story of Joanna Russ’ simply just stank. I think it had to do with a hippopotamus farting.

HARRISON: Okay, that’s what I mean. Not only fans but readers–they say, What’s this? Oh, Quark, I’ll give it a try. They read number one and then say, I’ll never buy this again. So when Quark 2 comes out they get people who haven’t read Quark 1, and so on. Pretty soon you’ve lost your audience.

TANGENT: I did think the artwork was worth showing around.

HARRISON: The visuals and graphics were very nice in there. I know that I enjoy some avante garde, so when I’m making an anthology I’ll put at least one story in for the fans who like that kind of stuff. I know in advance the rest of the readers are going to hate it. But I know I can afford that much. I know they’ll come to the next story and I’ll hit’em with one about rocket ships and time machines (Laughs). But I’ll put in a couple of poems, and I can hear them now: “Aw, man, whaddya want to put in pomes for?” Well, I like poetry, I’m a poetry buff–if you don’t like it just skip two pages. Or they’ll say, “What’s with all the pitchers?” I like pictures, they help break up the book.

I’ve only gotten one complaint about a story not being strict science fiction. That was from Sam Moskowitz. But most readers reading a science fiction book are not going to really care if a story isn’t true science fiction if it’s a good, well-written story.

TANGENT: I wonder what Lester del Rey would say about that.

HARRISON: Lester and I disagree a great deal about what goes into an anthology and what does not. (Laughing) He represents a somewhat more reactionary feeling in science fiction than I do, alright? (Laughs) Quote, unquote. I’ve known Lester for many, many years and we differ completely in our tastes. There you are.

~ End ~

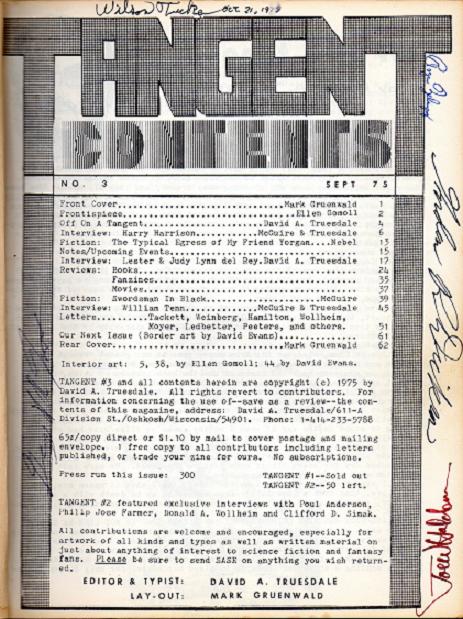

(The Table of Contents for Tangent No. 3, Sept. 1975. This issue had just appeared when I took copies to I-Con 1, Iowa City, IA over the Halloween weekend. The autographs you see were signed there. Left side, George R.R. Martin. Top, Wilson Tucker. Right side, Roger Zelazny, Gordon R. Dickson, and Joe Haldeman.)

Harry Harrison interview copyright © 1975, 2012 Dave Truesdale and Tangent/Tangent Online.

All rights reserved.