Tangent Online Presents:

An Interview with Donald A. Wollheim

(founder DAW Books)

Dave Truesdale & Paul McGuire III

Location:

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Event & Date:

Minicon 10

April 18-20, 1975

Originally appeared in Tangent No. 2, May, 1975

The following interview was one of nearly a half dozen I conducted at my first real science fiction convention. For the complete story of how these interviews came to be, please see the introduction to the William Tenn interview published elsewhere here.

This interview, however, may have been the first I ever did, though memory serves me ill after all these years. I remember being quite nervous at first, though shortly into the interview I was put at ease by the relaxed and friendly demeanor of both Don and Elsie. The first (and pretty poor, in retrospect) issue of the original Tangent had appeared a few months prior to Minicon 10, and my traveling companions and I were passing out copies to whomever seemed interested. I think we only mimeographed 100 copies. One of the features we were able to cobble together fairly well was the book review column, which contained several reviews of DAW titles. I remember sitting on one of the beds in the Wollheim’s hotel room, with Don sitting in a chair by the window and Elsie sitting behind me on the bed. Shortly into the interview I glanced behind me briefly and saw that Elsie had picked up that first issue of Tangent. She was reading the book reviews. My heart rate quickly accelerated and the room immediately became much warmer. My initial thoughts raced back to those DAW reviews. Had we given any bad reviews? Did we write good things about the DAW books, and did we sound intelligent? After stumbling through a few more questions and while listening to one of Don’s answers, I feigned having to adjust my position on the corner of the bed and stole a peripheral glance back at Elsie, who was still perusing the book reviews. I caught her catching Don’s eye and nodding in the affirmative. My imagination still tells me to this day that if not for that surreptitious, affirmative nod from Elsie to Don, that the interview might have turned out somewhat differently. God bless Elsie Wollheim.

Don’s professional career spanned so many decades–as writer, editor, anthologist, and publisher, that it would take an entire book to do justice to all that he did for, and meant to, the science fiction field. That said, here are a few facts and figures well known to those who know their SF history, but which might serve to whet the appetite for those desiring to learn more about this influential giant whose accomplishments helped to shape much of the SF field we know today.

Donald Allen Wollheim was born October 1, 1914 and died November 2, 1990. Elsie Wollheim was born June 26, 1910 and died February 9, 1996. They were married in 1943.

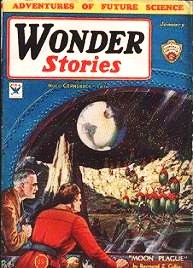

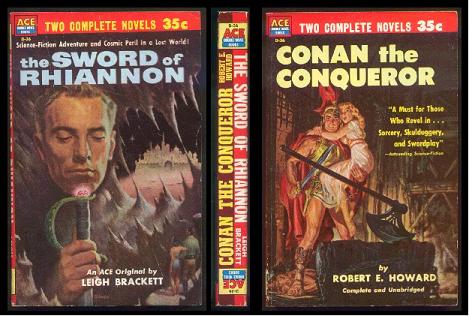

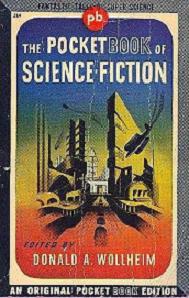

DAW’s first published story was in the January, 1934 issue of Wonder Stories (pictured at left). He was nineteen. One of his early short stories, “Mimic,” was released as a motion picture in 1997. Along with Stirring Science Stories he edited Cosmic Stories prior to World War II, and during the war, in 1943, DAW edited the first U.S. SF anthology, The Pocket Book of Science Fiction. DAW held the position of editor-in-chief of Ace Books from 1943-1946, then in the same position for Avon Books from 1946-1952. In 1953 he returned to Ace where he created the Ace Doubles, which introduced, for their first SF paperback appearances, the likes of Harlan Ellison, Leigh Brackett, Samuel R. Delany, Philip K. Dick, and John Brunner, among others.

DAW’s first published story was in the January, 1934 issue of Wonder Stories (pictured at left). He was nineteen. One of his early short stories, “Mimic,” was released as a motion picture in 1997. Along with Stirring Science Stories he edited Cosmic Stories prior to World War II, and during the war, in 1943, DAW edited the first U.S. SF anthology, The Pocket Book of Science Fiction. DAW held the position of editor-in-chief of Ace Books from 1943-1946, then in the same position for Avon Books from 1946-1952. In 1953 he returned to Ace where he created the Ace Doubles, which introduced, for their first SF paperback appearances, the likes of Harlan Ellison, Leigh Brackett, Samuel R. Delany, Philip K. Dick, and John Brunner, among others.

Controversy was not unknown to Don Wollheim, from his fiery days as a youth in one of the earliest fan organizations, The Futurians, to his publishing of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings epic in the 1960’s. DAW published the first-ever mass-market edition of Tolkien’s masterwork under a cloud of controversy. When he asked Tolkien permission to reprint the work in the U. S., Tolkien declined, on the grounds that he didn’t wish to see his work printed in a “degenerate” format (the paperback). The story goes that Wollheim, perhaps angered, discovered that the copyright holder and publisher, Houghton-Mifflin, had failed to protect the work in the U. S. Using this perceived loophole, DAW published the trilogy in an “unauthorized” paperback edition, which eventually gave rise to the fantasy resurgence and boom we witness today. Though he paid Tolkien appropriate remuneration, incensed U. S. Tolkien fans brought the case to court, where it was decided that DAW had infringed on the original copyright. Nevertheless, and according to daughter Betsy Wollheim, DAW’s publishing of the Tolkien trilogy in paperback “was really the Big Bang that founded the modern fantasy field, and only someone like my father could have done that. He did pay Tolkien, and he was responsible for making not only Tolkien but Ballantine Books extremely wealthy. And if he hadn’t done it, who knows when — or if — those books would have been published in paperback.”

Controversy was not unknown to Don Wollheim, from his fiery days as a youth in one of the earliest fan organizations, The Futurians, to his publishing of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings epic in the 1960’s. DAW published the first-ever mass-market edition of Tolkien’s masterwork under a cloud of controversy. When he asked Tolkien permission to reprint the work in the U. S., Tolkien declined, on the grounds that he didn’t wish to see his work printed in a “degenerate” format (the paperback). The story goes that Wollheim, perhaps angered, discovered that the copyright holder and publisher, Houghton-Mifflin, had failed to protect the work in the U. S. Using this perceived loophole, DAW published the trilogy in an “unauthorized” paperback edition, which eventually gave rise to the fantasy resurgence and boom we witness today. Though he paid Tolkien appropriate remuneration, incensed U. S. Tolkien fans brought the case to court, where it was decided that DAW had infringed on the original copyright. Nevertheless, and according to daughter Betsy Wollheim, DAW’s publishing of the Tolkien trilogy in paperback “was really the Big Bang that founded the modern fantasy field, and only someone like my father could have done that. He did pay Tolkien, and he was responsible for making not only Tolkien but Ballantine Books extremely wealthy. And if he hadn’t done it, who knows when — or if — those books would have been published in paperback.”

DAW co-founded (with Elsie) DAW Books in 1971, with the first four monthly titles released in April of 1972. It became the first all-SF mass-market publisher in history. Always known for innovation and nurturing new writers, among his many discoveries at DAW include Tanith Lee (though she had published previously in the U. K.), C. J. Cherry(h) (Cherryh once told me that DAW advised her to add the “h” to her name for publication purposes), Jennifer Roberson, Michael Shea, Ian Wallace, Tad Williams, and C. S. Friedman. Through DAW Books, he also provided U. K. authors a new audience, some of whom were Michael Moorcock, E. C. Tubb, Brian Stableford, Barrington J. Bayley, and Michael G. Coney.

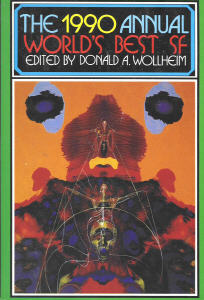

DAW began his yearly “Best of the Year” SF anthologies at Ace in 1965; from 1965-1971 with Terry Carr, then at DAW from 1972-1990 (the year of his death) with Arthur W. Saha.

DAW began his yearly “Best of the Year” SF anthologies at Ace in 1965; from 1965-1971 with Terry Carr, then at DAW from 1972-1990 (the year of his death) with Arthur W. Saha.

Of DAW, Robert Silverberg has said that he was “one of the most significant figures in 20th century American science fiction publishing,” and was “seriously underrated.” The late Marion Zimmer Bradley thought of DAW as “a second father,” Wollheim having published her work first at Ace in the 1950’s and then bringing her along to DAW Books where she continued to write some of her best Darkover novels for him. Elsie’s influence at DAW Books and on the stable of writers at DAW was famous and contributed greatly to the feeling of “family.” Many of DAW’s authors referred to Elsie as “my other mother.”

Following the interview you will find a letter from DAW to Tangent, which saw print in its third issue (September, 1975).

TANGENT: What was the real reason you broke away from ACE books?

DONALD A. WOLLHEIM: It was for economic reasons. ACE books was a very profitable and very steady company until the death of A. A. Wyn in 1967, who was its founder. It then came under new management who made certain changes, mostly economic investments in other fields, which made the situation more and more…uncomfortable, I’ll put it this way. Until it just became my feeling that there was no getting along. So I decided to strike out for myself.

TANGENT: They had more or less new priorities at ACE?

WOLLHEIM: Well, it’s not that. You know, a company makes a certain amount of money, and if they start spending it by buying other corporations they–their idea was to create a conglomerate, which was the thing in those days. They bought two or three other publishing companies and invested money and then found themselves in tight financial straits. And things were getting very ugly as far as their profitable side was concerned. It felt like to me that we were on a losing streak and I was naturally getting a little uneasy about all this.

TANGENT: How closely were you involved with Terry Carr in all of this?

WOLLHEIM: Well, in the first place let’s understand that I was vice-president of ACE books, editor-in-chief, and had been since the beginning. Terry Carr was hired by me as my assistant editor. And in the course of his work he launched the idea of the ACE Science Fiction Specials, which he did with my permission and A. A. Wyn’s permission. And, of course, Carr went on and it became kind of a difficult scene because Carr was running on his own and was ignoring other people’s advice around the place and the books were not paying off. Mostly because, I think, not because they weren’t good, but mostly because of his insistence on the use of a very standardized cover that turned out to be an economic disaster. News dealers couldn’t tell one from the other, readers couldn’t tell whether they’d read the book or not, and this made for enormous returns of the books themselves, and the books were terrifically unprofitable. It was a very dangerous thing to do, having those covers that way.

Carr himself also changed, becoming rather indifferent to the company. He’d come in late about 10:30 in the morning, and he built up a huge backlog of indifference. Finally it reached the point where, quite frankly, I fired him. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief because it had gotten to be a very unpleasant situation.

TANGENT: How did you go about starting DAW Books?

WOLLHEIM: I had begun to think of that only about four months before I actually left ACE. The whole problem with starting a paperback publishing company of course, is finding a distributor. There are only about twelve or so mass-market paperback companies. You have to get a distributor who will agree to put your books on sale, to help finance you, will give advances to publishers. You have to find your financing, you have to find your printer, all of these things.

So I had set myself a certain date, something like four or five months, to see if I could find a distributor who would back a new line of books. We talked to a number of people, and a number of printers and so on, and frankly for a long time it seemed quite impossible. And then we were quite fortunate to make a contact with New American Library. They had set up their own distribution company about three or four years before and were thinking of expanding. They knew about my reputation and about what I had done for science fiction and ACE books. And they just jumped for joy when I went in to see them. I could have gone in there in any capacity. I could have gone in as an editor there, or as a division of New American Library, or I could have gone in in just any fashion. I said I’d like to go in as a co-publisher. In other words, we are an independent corporation with what amounts to a partnership agreement with New American Library, whereby we use their offices, we use their staff and facilities and they of course charge that against us. But I would buy my own books and make my own contracts. We have our own logo, our own imprint, and they distribute our books and handle us.

And yet, of course, they do share our profits, and by this I mean it’s a very pleasant arrangement. It does not require my getting any outside financing. And it has worked out very nicely.

TANGENT: What criteria do you go by when you judge a book you might want for your line?

WOLLHEIM: My own taste. In the last analysis no editor can function unless it’s by his own taste. Now, I’ve been an editor since 1941, and it’s just my good fortune that apparently what I like at least 80% of the readers are going to like. This is just the way it is. An editor may come in who has better taste for himself, but if he only pleases 40% of the readers he’s not going to be an editor long.

Like I said, I happen to be fortunate. Most readers like what I like. The same is true for the artwork. Like I said–I’ve been with ACE for 19 years and in that period ACE grew to be the major publisher of paperback science fiction. Ballantine was a little ahead of us, but they had a slightly different type of book–somewhat more literary. But ACE was a pretty steady line; ACE was always profitable. So this shows you that whatever may be said, my taste was obviously right. DAW Books has continued to exercise the same taste. I’ve taken over some of the older ACE writers who have always done well: Marion Zimmer Bradley, E. C. Tubb, Philip K. Dick, and so on.

TANGENT: What do you look for in an unknown, or lesser known, writer?

WOLLHEIM: Well, the answer is very simple. In the first place I don’t think anybody should ever write science fiction unless he’s a reader, and doesn’t read it and doesn’t like it. I mean, if you read science fiction, if you like it, if you’re steeped in it, then you want to write it–you at least have some idea of what other people have done. You have an idea of what kind of themes can be handled, and you probably have some new thoughts or new variations of these. There’s an infinite number of variations. One of the things I’m personally very proud of is that I think I’ve introduced more new writers in the novel form, as well as paperbacks, too. Most editors are very cautious. I introduced Ursula K. Le Guin and Samuel R. Delany, both of whom came out of the slush pile. And there were a good many others, too. Gordon Dickson–I think the ACE Doubles did a couple of his very first books. Poul Anderson–way back in the early days of ACE–who had no other publishers, was published by me. Philip K. Dick–we did his first book.

I’m still doing this. In DAW Books I’ve managed to introduce at least two or three new writers a year. They haven’t always worked out, they don’t always work out, and this is not unusual, but occasionally they do and it’s worth the effort.

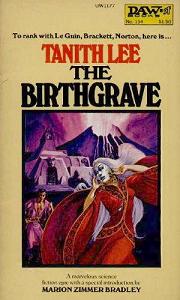

We’re very proud of a book coming up now, in June. It’s by a young Englishwoman, Tanith Lee–and I read this thing from the slush pile and it was so damn fascinating. The book ran very long–

TANGENT: Is it science fiction or fantasy?

WOLLHEIM: It is a science fiction work, but it reads like a Tolkien-type fantasy. She is a tremendously talented writer. Now, I’m taking a chance on her, this is a big book, four hundred pages or so, and I know I’m putting my neck out because she’s a totally unknown writer. But it is one hell of a novel. (Editor’s Note: The Tanith Lee novel referred to is The Birthgrave.)

Now see, this is what you’re talking about. If I start reading a manuscript from the slush pile, from an unknown, and it catches me, it holds me, that’s all I ask.

TANGENT: What repercussions would result if it didn’t sell?

WOLLHEIM: Well, I work for myself. The only repercussions would be in my own finances. In other words if, a few months after we publish the book, the report from the distributor says we’re not selling very many of these books, that we’re getting a lot of returns, I’m going to lose money, of course. If I, say, still worked for ACE books when A. A. Wyn was the owner, and I got called in a year later and he said we lost money on a book, he would have said well, don’t do this kind of thing again, but (chuckling) when I’m working for myself it’s only me who’s taking the risk.

Actually, it’s a lot easier to experiment with someone else’s money, because you know, you get called in and balled out, but it’s him that’s losing money (laughing). When it’s your own money and you’ve only got four or five titles a month, you get serious.

TANGENT: How long does it take a manuscript from your hands to publication?

WOLLHEIM: Anywhere from seven to ten months.

TANGENT: How closely do you work with the writers, as an editor, on the books you publish?

WOLLHEIM: Yes, well, if the book is not right, I’ll ask the writer to revise it; or make a change to it, or add to it, or take away from it, or alter a chapter. Also, a good many of our books are written by writers who have been writing steadily for us. Some of these are series’–they have the same background, and the author knows pretty much what he’s going to do, and I know what he’s going to do also. So, these things are arranged.

TANGENT: How much do you take it upon yourself to intrude, to edit?

WOLLHEIM: The ideal manuscript is one you don’t have to edit at all, of course. But there are certain authors who are very, very difficult to work with, who are very touchy. For instance, John Brunner. If you get a John Brunner manuscript you don’t touch it. It doesn’t even go to a copy-editor, because I know that the thing is accurate and if there are any typos in it they’ll be caught by the proofreader. But other authors will have to be very closely copy-edited. Somebody will go over these manuscripts line by line, will straighten out punctuation, will straighten out the spelling, will try to eliminate excess words, will change the formation of a sentence if it’s not clear.

Poul Anderson is somebody else you don’t have to worry about, in terms of editing. The man got to where he is because he is an artist, a craftsman. Like I said, John Brunner is also a craftsman who’s very proud of himself. He may not always be right, but you don’t argue.

TANGENT: What trends have you noticed, in the buying public in particular, since you began DAW Books?

WOLLHEIM: That’s hard to say. There are trends, yes, and it’s very subtle. I think there is a trend toward a little more sword & sorcery, a little more fantasy element. I notice that things do run in cycles. And there seems to be a great deal of material coming in, both from professionals and unknowns, and they all seem to work together, think together, on what I call uchronia novels. In other words, novels of What if– What would have happened if history had worked out differently.

TANGENT: How much should a writer take for granted in his audience?

WOLLHEIM: Apparently these days he can take an awful lot for granted. The science fiction reader has become much more sophisticated, in the sense that you don’t have to repeat the explanations. You’ve got to remember that most readers reading science fiction today have already probably passed through the comics magazines. You look–every bloody thing in those things is stolen from science fiction. They’re using those terms right to the ten or eleven year old. These kids are coming in already full of the terminology used in science fiction. They already know the words, they know what they’re going to read, they know the basic themes (chuckling).

TANGENT: Has this awareness on the part of the audience improved the quality of science fiction?

WOLLHEIM: It hasn’t improved the writing, but it’s made it easier to put things over. In other words, you don’t have to spend a lot of time explaining. I mean, they know what you’re talking about.

TANGENT: If a writer of science fiction or fantasy has such a wide berth of ideas to work with, and there are infinite variations to these ideas, how does one branch out in the sword & sorcery field, for instance, which is one of the more defined genres? Especially when someone like Lin Carter attempts to codify to the extreme what should be placed in a sword & sorcery tale–or even a fantasy tale in general? Take the relevant chapters in his non-fiction book Imaginary Worlds, for instance.

WOLLHEIM: (Laughing) Well, that’s his problem. Of course there are boundaries, and also things to be explored yet. It’s a wide open field.

TANGENT: How much do you pay for an original novel?

WOLLHEIM: An average rate these days is about $2,000 in advance, against royalties. This is for a novel of about 60,000 words.

TANGENT: Give us your typical day as a publisher, if you have such a thing.

WOLLHEIM: Yes, we do. I have deadlines which I have to meet. I am actually publishing five books a month. In any one day I’m concerned with a time span of at least six months. I am, in the first place, working on–let’s see, this is April. I’m looking forward to receiving the May books which will be coming off the presses in about two or three days. And, you know, we’re keeping an eye on them to see where they come in, and also we’re writing publicity for the June titles which goes out to the promotion department. For the July books, we’ll see cover proofs for the July titles. Like we just got them in only yesterday and they have to be darkened because the lettering came out too light. They’re in the proof stage. For August books we’ll be seeing–well now, they will have gone to press, the manuscript will have gone to press–the August titles will be coming back from press. The September titles are going to press. That means the October titles are being copy-edited. For the October titles we have sent xeroxed copies out to the artists to get color sketches. November titles will already have been selected, and we will be getting some estimate on the length of the books. December–just a week and a half ago I gave New American Library a listing of what the December titles are going to be. They will put that up on their schedule. For January I have a notation in my desk as to what my January titles are going to be, but I haven’t given it out yet. I won’t give that out for two weeks. February I also have a vague idea of what’s going to be.

Meanwhile, I have manuscripts waiting to be read. And I have manuscripts out on project which are being written, two of which are overdue at the moment. One is from Philip Jose Farmer, and one is from Marian Zimmer Bradley.

TANGENT: Do you read every manuscript personally?

WOLLHEIM: Yes, I do. So, in other words, an average paperback editor’s day is really not very different from mine, but my responsibility is entire. It covers a range of seven or eight months. On top of that, we must be thinking constantly beyond that. In other words, when I’m reading manuscripts, I’m not reading for February of 1976. I’m reading for March, April, May, 1976. I’m working a year ahead.

And we’re getting reports on our February titles, which are speculative. We’re getting finalized reports on the books from eighteen months ago. The truth is, you do not get a finalized sales report–a report which is 99% accurate–until about eighteen months after the book is published. That’s when all the accounts are in, credits have been received; and so now we know how well we have been doing in December of 1973.

You’re never finished. This is the kind of business where you never know where you are–you don’t know where you are for eighteen months. You’re always working in a span of two years. It’s a very strange business. In essence, I’m juggling about forty titles in my head at all times. And those are bought titles, not the one’s that I’m looking at.

TANGENT: Do you have ulcers?

WOLLHEIM: (Chuckling) No, I don’t have ulcers. I’ve been in this business for some thirty years. While I was at ACE, I must tell you, I was handling some twenty titles a month. I didn’t have to read them all, but I still had to keep track of where they were. And that included westerns, detectives, gothics, and a nurse novel occasionally. So, I’m very used to this kind of juggling. To me, juggling only five titles a month is a rest.

I like what I’m doing, I really do. We get away, we take a vacation. This has been my habit for years. We’re invariably meeting people, science fiction authors, and so on. It’s a game; I like it or otherwise I couldn’t survive.

TANGENT: You also did some fine writing of your own in past years.

WOLLHEIM: (Chuckling) Yeah, in between. I remember I sold my first short story in 1934 to Hugo Gernsback. Took two years to get paid for it (laughing). I got my first job putting out a shoestring magazine back in 1941 called Stirring Science Stories. And everybody, all our friends in the Futurian Society donated stories free. Cyril Kornbluth’s first stories appeared there–

TANGENT: Where can those stories be found now?

WOLLHEIM: (Laughing) In the hucksters’ room at high prices.

ELSIE WOLLHEIM: Didn’t Isaac Asimov get paid five dollars for a story?

DON WOLLHEIM: Yeah, he was very commercial even back then (chuckling).

TANGENT: Well, you certainly have paid your dues, knowing what you’ve worked on since then.

WOLLHEIM: Oh, yeah. I also sold, in 1943, the first anthology of science fiction to Pocket Books. It was the first book ever to use the words “science fiction” on the title.

WOLLHEIM: Oh, yeah. I also sold, in 1943, the first anthology of science fiction to Pocket Books. It was the first book ever to use the words “science fiction” on the title.

TANGENT: Looking at the pulps in science fiction, I can’t help but wonder how long it’s going to be before you, as a publisher, feel the crunch of the economic situation.

WOLLHEIM: Well, the pulps are dead. Science fiction is the only one to survive in that field. There’s no western pulps, no detective pulps. Analog has survived very well; Galaxy is in trouble because I think their publisher is in trouble–I don’t know why. I think they made a number of foolish investments in other areas. It’s not Galaxy‘s fault as a magazine. They’re paying slow. SFWA has been in a fight with them, and that’s still going on. Fantasy and Science Fiction is still going, but I understand it’s not making too much of a profit. They’re just managing to keep going, to get past. Fantastic and Amazing manage to survive on the barest of margins. They do it because they have a very low budget. They’re paying Ted White almost nothing.

TANGENT: Thank you very much, Mr. Wollheim.

WOLLHEIM: My pleasure.

***

Afterword

Letter from Donald A. Wollheim

Somewhere between Minicon 10, in April of 1975, and September, 1975 (when Tangent #3 appeared), I had read the just published DAW debut Tanith Lee novel The Birthgrave. While for some reason still unbeknownst to me (and I’m quite sorely baffled these many years later), I did not print in the interview the line where DAW mentions that there was to be a special introduction to The Birthgrave by none other than Marion Zimmer Bradley. The MZB introduction was missing from the published novel. After reading The Birthgrave and writing to Don to express my enthusiasm for it, he was kind enough to take the time to write back, said letter seeing print in the LOC (letters of comment) column:

“Donald A. Wollheim

1301 Avenue of the Americas

New York, N. Y. 10019

Dear Mr. Truesdale:

Thanks for your very enthusiastic letter about The Birthgrave. Though the book has been out about six weeks, you are the first to write the publisher about it. Which should tell you something about why editors of books become cynical.

I understand there are favorable reviews coming up in Analog on this book and other fanzines…but so far, not much comment.

As for the MZB introduction, this is a real foul-up–somewhere between my desk and the printer, the manuscript became disconnected from the novel and vanished–because when the book appeared, it was not to be seen. Believe me, it was a shock to me…and still a sore point as to how it happened. And why it wasn’t detected as missing in the proofs….

As for the MZB introduction, this is a real foul-up–somewhere between my desk and the printer, the manuscript became disconnected from the novel and vanished–because when the book appeared, it was not to be seen. Believe me, it was a shock to me…and still a sore point as to how it happened. And why it wasn’t detected as missing in the proofs….

I enclose a Xerox of the introduction.

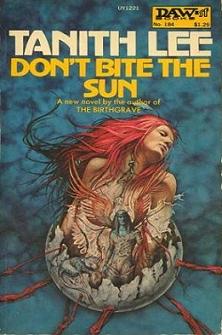

I have two more Tanith Lee novels on hand. The next, Don’t Bite the Sun, is utterly different and just as delightful (and rather shorter); and due for publication in February 76. The third novel is as long and as complex and marvel-filled as her first and will probably not be coming until the middle of next year. Working title: The Storm Lord. (I say working title, because this has been coming in in parts as her typist finishes each section.)

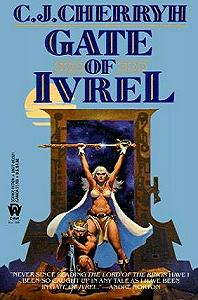

Incidentally, in March 1976 I will have the first novel of another lady author every bit as good as Tanith.

Cordially,

Don Wollheim”

As everyone now knows, that other “lady author every bit as good as Tanith,” turned out to be C. J. Cherryh with her first novel Gate of Ivrel. As to Tanith Lee’s second novel mentioned in Don’s letter, Don’t Bite the Sun, I was mightily impressed by it (as was everyone else). I wrote up my own review of it for a future issue of Tangent, sent the issue along to Don and thought nothing more about it. Then comes, in January of 1977, DAW Books No. 226 and Tanith Lee’s third smash book Drinking Sapphire Wine. Thumbing through the book I came to the final page, just inside the rear cover, where DAW had placed reviewer blurbs for Don’t Bite the Sun. There were four of them; one from MZB, one from the late Richard Delap’s F&SF Review, another still from a fanzine I’d never heard of, Drexel Triangle, and lo and behold the last from my Tangent review! I was on cloud nine and then some, as you might imagine. What a tremendous bit of egoboo for the editor of a just-begun little fanzine! Tangent‘s first review blurb! I still get a thrill thinking about those days when I and a few friends decided to publish a fanzine; within a short but exciting period of time we’d somehow actually published our own fanzine, been to our first SF convention, met for the first time a number of SF and Fantasy authors, editors, and publishers (which was more than enough right there to fuel our enthusiasm for years to come), and now we were blurbed! Heady days for neophyte fans, indeed. The seasons never changed for us back then; it was summer all year ’round.

As everyone now knows, that other “lady author every bit as good as Tanith,” turned out to be C. J. Cherryh with her first novel Gate of Ivrel. As to Tanith Lee’s second novel mentioned in Don’s letter, Don’t Bite the Sun, I was mightily impressed by it (as was everyone else). I wrote up my own review of it for a future issue of Tangent, sent the issue along to Don and thought nothing more about it. Then comes, in January of 1977, DAW Books No. 226 and Tanith Lee’s third smash book Drinking Sapphire Wine. Thumbing through the book I came to the final page, just inside the rear cover, where DAW had placed reviewer blurbs for Don’t Bite the Sun. There were four of them; one from MZB, one from the late Richard Delap’s F&SF Review, another still from a fanzine I’d never heard of, Drexel Triangle, and lo and behold the last from my Tangent review! I was on cloud nine and then some, as you might imagine. What a tremendous bit of egoboo for the editor of a just-begun little fanzine! Tangent‘s first review blurb! I still get a thrill thinking about those days when I and a few friends decided to publish a fanzine; within a short but exciting period of time we’d somehow actually published our own fanzine, been to our first SF convention, met for the first time a number of SF and Fantasy authors, editors, and publishers (which was more than enough right there to fuel our enthusiasm for years to come), and now we were blurbed! Heady days for neophyte fans, indeed. The seasons never changed for us back then; it was summer all year ’round.

And finally, for those who have been wondering about this next with baited breath–No. I do not still have in my possession the “lost” copy of the MZB introduction to Tanith Lee’s first novel The Birthgrave, that Don so kindly sent along in Xerox. I would never intentionally toss something like that out, I don’t know what happened to it, and I’d forgotten all about it until I reread Don’s letter for the reprinting of his interview. I am now dutifully kicking myself for ever having let it slip away. Maybe a copy might be discovered in either MZB’s or Don’s papers, if perhaps some erstwhile bibliophile would take it upon him or herself to see if it still exists and publish it, filling in this small crack in the wall of the history of DAW Books.

All rights reserved.