Tangent Online Presents:

An Interview with Ben Bova

(November 8, 1932 — November 29, 2020}

(Ben Bova photo © 1976, 2020 Dave Truesdale}

Locations:

Stevens Point, WI, March 4, 1976

Minicon 11, Mpls., MN, April 1976

Oshkosh, WI, September 21, 1976

Interview originally appeared in Tangent No. 6, Winter 1977, and is reprinted here for the first time. Cover art by Robert Fuller.

December 1, 2020 Preface to Original 1977 Introduction

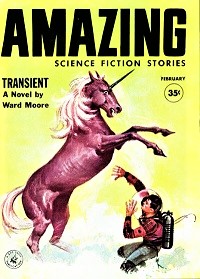

A few brief comments and two anecdotes about Ben before the interview, the material for which was acquired over several meetings during 1976, all of 44 years ago, if you can believe it. Ben’s first novel, The Star Conquerors, appeared in October 1959 as #33 in the Winston Science Fiction series of juveniles, and his first professional short fiction sale saw publication in the February 1960 issue of Amazing Stories (cover at right) under the editorship of Cele Goldsmith. At the time of this interview most of Ben’s career as writer (many short stories and novels), essayist, and editor had hardly gotten started. So what you are about to read comes from roughly the first quarter of Ben’s entire SF career, and is most certainly a product of its time. The vast percentage of the recognition and awards he would receive would come his way in the 44 years following the interview. For those desirous of a more complete accounting of Ben’s works and awards (which are legion) I suggest the indispensable ISFDB, and his wikipedia page.

A few brief comments and two anecdotes about Ben before the interview, the material for which was acquired over several meetings during 1976, all of 44 years ago, if you can believe it. Ben’s first novel, The Star Conquerors, appeared in October 1959 as #33 in the Winston Science Fiction series of juveniles, and his first professional short fiction sale saw publication in the February 1960 issue of Amazing Stories (cover at right) under the editorship of Cele Goldsmith. At the time of this interview most of Ben’s career as writer (many short stories and novels), essayist, and editor had hardly gotten started. So what you are about to read comes from roughly the first quarter of Ben’s entire SF career, and is most certainly a product of its time. The vast percentage of the recognition and awards he would receive would come his way in the 44 years following the interview. For those desirous of a more complete accounting of Ben’s works and awards (which are legion) I suggest the indispensable ISFDB, and his wikipedia page.

Ben Bova anecdote #1: You’ll notice the picture of Ben I chose to use for the interview (same as for the original publication) shows Ben only from the waist up. It was taken at MidAmericon (BigMac), the 1976 worldcon in Kansas City, MO the day after the Hugo award presentations the evening before. I wanted a photo of Ben with his Hugo for editing Analog but was afraid I’d miss him, as many attendees were packing up to leave. I called his room and fortunately he picked up. He said he’d be happy to give me a few minutes for a photo or two and to come on up. When I got there Ben said he was on his way to the pool. He was dressed in a loose-fitting shirt, shorts, and flip-flops. As I began to take the first picture he saw me angling the camera and stepping back to get all of him with his Hugo in the shot. He stopped me and said, “Only above the waist, please. No legs.” I don’t remember if I chuckled or not but of course did as he asked. Ben Bova doesn’t want something like a permanent shot of him showing his legs was okay with me.

Ben Bova anecdote #2: In late September of 1976 the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, where I had returned to hopefully finish up my college experience after a hiatus of several years, was holding one of those week-long Arts festivals or multi-disciplinary open house fairs (or whatever they’re called). A friend of Ray Bradbury’s who worked in the radio/television department at the university, Robert Jacobs, thought it would be a neat deal if we could get Ray to come to Oshkosh and speak. (At least this is how I remember it now, with Robert suggesting Ray come to the festivities). So we got in touch with Ray, who regretfully declined because he didn’t fly. I then suggested we ask Ben if he would like to come to Oshkosh to give a speech during the aforementioned week of special events. I’d already met and talked with him twice earlier in the year, the last time being a mere few weeks before at the Kansas City worldcon. So I call Ben at his Analog office in NYC, name the price the university gave me as being what they were able to afford for his services, and Ben agreed. (Psst. Don’t tell anybody, but it was a thousand dollars for a one hour speech. And those were 1976 dollars.) Ben arrives and gives a packed room a great, well-received speech on the Viking landings on Mars, collects his check, and we go to one of the local restaurants for snacks and adult beverages till very late. I’m asking questions and taping all of it. Ben flies home the next morning and all is well with the world. Almost. It seems my tape recorder had malfunctioned and nothing had been recorded. All that good stuff was gone. Beside myself, I called Ben and told him what had happened. He said we could do something by long distance phone. I thanked him for the offer but said there was no way I could afford the long  distance phone charges. He said he’d be glad to help and that Analog would take care of the phone charges. So a major portion of the interview ended up being from that taped phone call. I had one of those little rubber suction cups you stuck to your land line telephone receiver back in the day, with the other end of the thin rubber line plugged into a tape recorder. Low tech saved the day. I’ll never forget how accommodating and gracious Ben was about the whole thing. He went out of his way to help “the kid,” (I was still just shy of my 26th birthday) and I’ll always remember his kindness. Last time I saw Ben was in 2007 at the Heinlein Society’s meeting celebrating the 100th Anniversary of RAH’s birth, combined with the John W. Campbell/Theodore Sturgeon awards ceremonies held that year in Kansas City, MO. Ben won the Campbell for Best Novel of 2006 for Titan.

distance phone charges. He said he’d be glad to help and that Analog would take care of the phone charges. So a major portion of the interview ended up being from that taped phone call. I had one of those little rubber suction cups you stuck to your land line telephone receiver back in the day, with the other end of the thin rubber line plugged into a tape recorder. Low tech saved the day. I’ll never forget how accommodating and gracious Ben was about the whole thing. He went out of his way to help “the kid,” (I was still just shy of my 26th birthday) and I’ll always remember his kindness. Last time I saw Ben was in 2007 at the Heinlein Society’s meeting celebrating the 100th Anniversary of RAH’s birth, combined with the John W. Campbell/Theodore Sturgeon awards ceremonies held that year in Kansas City, MO. Ben won the Campbell for Best Novel of 2006 for Titan.

Original 1977 Introduction

Most of the following interview is the outcome of a visit to Oshkosh, Wisconsin by Ben on September 21, 1976, at which he spoke exclusively on the Viking landings on Mars. Other parts of the interview are taken from talking with Ben at Steven’s Point, Wisconsin on March 4, 1976 and at Minicon 11 in Minneapolis in April of 1976.

When I asked Ben to send along an updated list of his works he sent me the following, which will also serve the dual purpose of an introduction–and a better one than I could write anyway. [Editor’s note: I am leaving off the long list of Ben’s fiction and non-fiction works accompanying the next four paragraphs. They took up more than a full page in the original print version of the interview, but are unnecessary here.]

“Ben Bova is a novelist, lecturer, and editor of Analog Science Fiction – Science Fact magazine, the most widely read and influential science fiction magazine in the world. He received the Science Fiction Achievement Award (Hugo) for Best Professional Editor for four consecutive years, 1973, 74, 75, and 76.

“The author of more than forty books of both fiction and non-fiction, Bova has also been a working newspaperman, an aerospace executive, a motion picture writer, and a television science consultant. As manager of marketing for Avco Everett Research Laboratory, in Massachusetts, he has worked with leading scientists in advanced research fields such as high-power lasers, magnetohydrodynamics (MHD), plasma physics, and artificial hearts. Prior to joining Avco, he wrote scripts for teaching films for the Physical Sciences Study Committee, working with the MIT Physics Department and Nobel Laureates from many universities. Earlier, he was a technical editor on Project Vanguard. He also worked on several newspapers and magazines in the Philadelphia area.

“Bova has lectured on topics ranging from the history of science to the future of cities. He has directed science fiction film courses at the Hayden Planetarium (American Museum of Natural History) in New York. He was born in Philadelphia, where he attended Temple University and received a degree in journalism.

“His short stories and articles have appeared in all the major science fiction magazines, as well as in Harper’s, Smithsonian, American Film, Vogue, The Writer, and many other periodicals. His book, The Fourth State of Matter, was honored as one of the best science fiction books of 1971 by the American Librarian’s Association. Starflight and Other Improbabilities was selected as a Junior Literary Guild book in 1973. He was the 1974 recipient of the New England Science Fiction Association’s E. E. Smith Memorial Award for Imaginative Fiction.”

TANGENT: How did you get the job as editor of Analog following the death of John W. Campbell in 1971, where had you worked before that, and what had you done?

BOVA: I had been working in the research industry for about fifteen years or so, starting with Project Vanguard. I was with the Martin Aircraft Company building the satellite launching rocket. And then I worked for about a dozen years up in Boston, most of the time for a research company called the Avco Everett Research Laboratory.

I’d been writing science fiction steadily all through that time. When Campbell died, the management of Conde-Nast asked Kay Tarrant to draw up a list of possible successors. Kay, in turn, asked the steady contributors to the magazine to prepare lists. I was not a steady contributor but my name popped up on the list. They called me down to New York, asked me if I was interested—and frankly I was a little scared of it. But I figure it’s like being President; you may screw it up but you don’t say no.

TANGENT: Had you had any experience in editing, or in anything of this sort before?

BOVA: I had started as an editor on newspapers and magazines—small things—in the local Philadelphia area, and in fact I told the executive editor of Conde-Nast, the man who interviewed me for the job, that I didn’t know anything about producing a national magazine, and he sort of chuckled and said look, we know everything there is about producing national magazines, what we don’t know about is science fiction. So, if you provide that knowledge we’ll get the magazine to the right places.

TANGENT: What are your interests in the visual media aspect of science fiction, and how did you get into this?

BOVA: Mainly I got into it through Harlan Ellison. We’ve worked together on several projects, all of which turned out rather aggravatingly. Harlan had a damned good idea on The Starlost and was beaten into the ground by the Hollywood ‘moguls’, as they say. I was the science advisor, which is like being the science advisor to Richard Nixon (chuckles). I gave advice and it was totally ignored. And I did a novel about it all called The Starcrossed. It’s a tongue-in-cheek novel that was sort of inspired by all the frustrations of trying to do good science fiction with bad people.

BOVA: Mainly I got into it through Harlan Ellison. We’ve worked together on several projects, all of which turned out rather aggravatingly. Harlan had a damned good idea on The Starlost and was beaten into the ground by the Hollywood ‘moguls’, as they say. I was the science advisor, which is like being the science advisor to Richard Nixon (chuckles). I gave advice and it was totally ignored. And I did a novel about it all called The Starcrossed. It’s a tongue-in-cheek novel that was sort of inspired by all the frustrations of trying to do good science fiction with bad people.

TANGENT: Look at how long it’s taken them to do a good police show—something like twenty years. How long will it be before we see a good science fiction show on TV? Isn’t it simply a matter of the money and the viewing public?

BOVA: No. I think largely it depends on turning around the preconceived notions of the producers, the people in Hollywood, that science fiction means spectacular special effects and damn little else.

TANGENT: Don’t they give the mass market audience what they seem to want?

BOVA: You mean what the audience is buying? The audience will buy whatever is put on the tube. I think the current year in television shows that. You put dogs defecating on television and you’ll get forty million people watching it.

TANGENT: Do you have any plans for any movies of your own? Are you involved with any movies right now?

BOVA: Yes. I have a novel coming out in June called The Multiple Man which is only marginally science fiction, and thank god it will require very little in the way of special effects—

TANGENT: Who’s doing it?

BOVA: The publisher is Bobbs-Merrill, and there’s a production outfit on the coast that is very, very close to closing a deal on a major production. This will be an eight to twelve million dollar movie.

TANGENT: Would you tell us vaguely what it’s about?

BOVA: No.

TANGENT: (Laughing) Not a hint? Anything?

BOVA: Well, I’ll tell you the opening scene: A young, vigorous, terrific, groovy President—JFK type President of the U.S.—is giving a speech, and in the alley behind the auditorium a secret service security guard finds a dead body, which looks exactly like the President, down to the fingerprints, retinal patterns, and everything else.

The story is told through the viewpoint of the President’s Press Secretary, who begins to find out that this is not the first time a duplicate of the President is found dead…of no apparent cause. And, we go on from there.

TANGENT: What are your plans for the future? Do you find you like what you’re doing with Analog?

BOVA: I’m getting a terrific kick out of doing Analog, it’s a lot of fun. I think if it begins to get repetitious and boring, not only will I get tired of it but so will the readers. The main thing in Analog I think, is to try to do new things all of the time, and keep the readers moving forward.

There’s a trick to this—Analog has a very large audience. You don’t want to move or change things so rapidly that you turn off the audience. But if you keep doing exactly the same thing month after month you’ll bore them to death and you’ll lose them that way, So the editor, I think, has got to be maybe half a step ahead of the audience. If he gets too many steps ahead he loses them; if he stays right in step with them he loses them. So, the job of a leader is to lead.

TANGENT: What is the major difference in the publisher of Analog and some of the other pro science fiction magazine publishers? Is it just the money that allows Conde-Nast to produce and distribute a better product?

BOVA: Yes. You see, in this cruel world money makes money, and Ferman’s Mercury Publications is essentially a family endeavor. UPD which publishes Galaxy is in considerable financial difficulties. Sol Cohen has always operated on a shoestring, less than a shoestring with Amazing and Fantastic. Whereas Conde-Nast is one of the two or three top magazine publishers in the country.

TANGENT: Where does Conde-Nast make their money?

BOVA: Well, they’ve got a wonderful captive market—all the women in America. They publish Vogue and Glamour and Mademoiselle and do wonderful articles about this year’s styles of clothes, and the female sexuality, and it’s all paid for by ads that are selling the same old crap that they were selling twenty yeas ago. The women dutifully go out and change their hemlines, and wear these rags that vary in the design, and uh, look terrible for the most part.

TANGENT: That seems strange when you think that Analog—SF in general, really—is a male dominated readership.

BOVA: No, the reason they have Analog is because Conde-Nast absorbed the Street & Smith publications back in 1960, and killed off most of the Street & Smith magazines, which were shaky. But they had this strange little science fiction magazine called Astounding, and this towering figure named John Campbell running it, and they didn’t know anything about science fiction but they knew that this magazine was the number one magazine in the field–and they liked being number one.

And, for crasser reasons, Analog/Astounding consistently makes a profit month after month. John Campbell used to say Analog is a gold mine—a teeny weeny gold mine because it’s a very, very small profit—but it is consistent, and no publisher in his right mind will turn down a steady money maker. Even though it’s a small amount of money it helps defray the overhead expenses, it looks good on the accounting books, and with something like Vogue where they make a million dollars one month and lose two hundred thousand the next, you know, there’s always hysteria and heart attacks.

Analog s-a-i-l-s along, gaining readers, losing a few maybe when economic times are tough, but they come back again when times are better.

So, it’s interesting. We’ve lost some newsstand circulation over the past two years, but our subscription numbers are constantly rising.

TANGENT: What exactly is the circulation of Analog at this time?

BOVA: Our last figures were about 110,000 per month.

TANGENT: Is that worldwide or just U.S.?

BOVA: That’s total. We estimate, rather conservatively, that for every magazine copy bought, there’s about three to five readers. We figure there are about half a million readers of Analog worldwide.

TANGENT: How many copies go overseas each month?

BOVA: A small percentage. Oh, I’d say around 5%.

TANGENT: You would like to see Analog taught in science fiction courses instead of the older, classic novels.Why is this, and how should one teach a science fiction course?

BOVA: Well, of course, I’m partial to Analog for obvious reasons, but I do feel that an awful lot of science fiction courses are taught from a completely historical approach, like English literature classes. And it always seemed kind of odd to me to teach the literature of the future the way you would teach Medieval literature.

Science fiction, God knows, is a different branch of writing, and to try to tell, to show the students what the field is all about—and it’s a very vital and alive field—and to try to show it from the standpoint of novels that are twenty to thirty years old, is ludicrous. Science fiction is burgeoning, it is vital, it is alive, it speaks to the issues not just of today but of tomorrow. And to go back to some books that might have been very fine, and still are, from a historical perspective, that deal with issues that are pretty much dead and forgotten, seems to me to be quite silly.

TANGENT: What role, if any, does the Analog Annual play in this?

BOVA: The Analog Annual is simply recognition of the fact that there are more good stories than we have pages to print in our monthly magazine. It’s an attempt to do two things. First, to give room to these stories and these writers, and secondly to show some of the readers who don’t go to the magazines for fiction, who go to paperback books, that there is a magazine out there that they might like.

TANGENT: You’ve been a proponent of science fiction as the mainstream literature of today. Could you explain some of your feelings on this?

BOVA: Aside from the fact that I think there’s much more good writing in science fiction than people outside the field recognize, I believe that a live literature speaks to things that interest the people who are reading it. Science fiction is a contemporary literature, no matter if the stories are set in the future or they’re set in places outside the Earth. Much of what goes down in science fiction is concerned about today’s people and today’s problems, shown in a future perspective, perhaps.

Now, most of the other literature—I think if you look at the best-seller list—is either escapist or…I hesitate to say trash, but that’s what it is. A lot of it is simply reiterations of sad stories about people who can’t cope with society and who’ve given up, or are about to give up. In science fiction I think we deal more with the real forces that are moving people and moving society, that show how these forces work and how human beings interact with them.

TANGENT: Harlan Ellison, another promoter of science fiction as mainstream literature, in a recent interview in Vector, the Journal of the British Science Fiction Association, has openly stated that three men he admires greatly are doing more harm to the growth of science fiction than anyone he knows. They are Forry Ackerman, Lester del Rey, and Don Wollheim; the first and last because of what they publish, and Lester because of his conservative views. What would you say to this? Can a few people with large influence really affect the field? Are the above retarding SF?

BOVA: I think Harlan would agree that the field is growing, that there are new magazines coming into being; there are something like forty or fifty new SF titles being published in the book market each month. Science fiction is very active in motion pictures and in television, even shows that have nothing to do with SF are using a lot of material that would have been called science fiction five or ten years ago. We have SF records, a Science Fiction Book Club, SF neckties; my God, I don’t see how Forry or any legion of people can be hurting the field when the field is growing so rapidly.

TANGENT: So there’s yet room for everything even though Forry publishes stuff like Perry Rhodan?

BOVA: Well, that’s true, but I think you have to call Sturgeon’s Law into effect: 90% of everything is crap. And Perry Rhodan will be read by youngsters who may go on to read other things that will be more interesting. I got into science fiction largely by reading the early works of Edgar Rice Burroughs, the John Carter of Mars stuff. Now, that was the Perry Rhodan of its day. There’s never been a more popular bad writer in the history of the English language than Edgar Rice Burroughs. But he did bring a lot of readers into science fiction.

TANGENT: Again, I would like to congratulate you on winning this year’s Hugo Award as Best Professional Editor, but in your acceptance remarks you said you felt many other editors were overlooked. Would you explain this—and who was overlooked?

BOVA: Thank you.

I’m afraid that when it comes to the balloting for the Hugo as Best Editor—the rules were changed in 1972. Previously the vote had been for Best Magazine. In 1972 the rules were changed to recognize the fact that much new, original science fiction was published outside the magazines, so that book editors, anthology editors should be included. So, since the rules were changed they have awarded the Hugo to the editor of Analog four years in a row. Well, that’s marvelous. I love getting it, and as I said, I wouldn’t mind getting it every year for the rest of my life. I’m very pleased with it, that the fans and readers want to give me the award, but there are other editors in the field. I think any block voting or any voting automatically—more or less by reflex—is bad for the awards, is bad for the field. There are many editors in the book business who are totally anonymous as far as the fans are concerned.

TANGENT: Like who?

BOVA: I think maybe Adele Hull at Pocket Books, although she’s very new. But nobody knows her. Don Benson, who’s been working at Pyramid, and more recently at Dial Press is a fine science fiction editor with a great reputation among the writers in the field. The fans have never heard of him. Judy Lynn del Rey, who everybody knows, has never even been nominated. And she’s the SF editor at Ballantine, of course. Fred Pohl, who’s been the SF editor at Bantam, has never been nominated since he left Galaxy. And as it is, some of the people who are nominated—the anthology and magazine editors—I think should be considered more seriously.

I would like to see a situation where after somebody gets a Hugo three years running, the rules read that he or she is excused from Hugo competition for a year. Because I do think we tend to get, in certain categories, a reflex vote, and I think it would be a good thing to force the fans to think a little more deeply.

TANGENT: Are you involved at all in the Science Fiction Research Association?

BOVA: No. Only as a detractor.

TANGENT: What do you think of it?

BOVA: They’re a bunch of toads.

TANGENT: (Laughing) It’s not generally a fruitful organization, then?

BOVA: I really don’t know too much about it except that they seem inept, their scholarship is slipshod, they really epitomize all that people shudder about when they think of a bunch of academicians meeting in the dark of the moon.

TANGENT: Do you think there should be any additional criteria for evaluating a science fiction work? Normal critical evaluation just doesn’t seem to work sometimes.

BOVA: No. I don’t believe science fiction should be treated any differently than any other kind of literature.

TANGENT: It is different though, in some respects.

BOVA: But then you could say detective fiction should have its own set of rules, and gothic fiction should have its own set of rules, and so on.

No, I think stories are stories and books are books, and they should all be read and enjoyed…. I do think you’re right to this extent, that it takes a little more knowledge and understanding to read the most classical or stereotype science fiction where an awful lot of the science fiction shorthand is used, but I see no reason why an intelligent reader who’s never picked up a science fiction book before, cannot come to the best books in the field and enjoy them just the way they enjoy the classics in any field.

TANGENT: Are the critics included in this, too?

BOVA: Well, that’s assuming the critics are intelligent readers. (Chuckling) Some are and some aren’t. But truly, if you come to a book in another field, say some arcane novel about the Russian frontier in the 1820s, and it has so much detailed information in it that it’s inaccessible to you, so many local words of jargon that you couldn’t understand it, the chances are that no matter how interesting the book seemed, you would put the book away. And this applies to science fiction, too. Lots of science fiction is written for the science fiction fans who understand this jargon and know all the code words, and all the background, and just love that kind of story. Fine. But there are lots of other readers out there, and I think people should be writing books and stories for them.

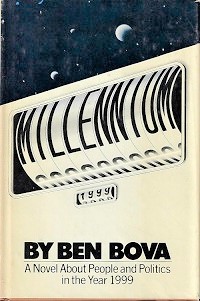

TANGENT: Could you tell us the motives, the forces, that prompted you to sit down and write Millennium?

BOVA: (Chuckles) My God, I started that book in 1949, and at that time it was a very different novel, and it dealt mainly with the race to get to the moon. At that time it was a cold war situation and the Russians were well ahead of us in space research and their space operations, and we had to get a crash space program going to get Americans on the moon ahead of the ‘dirty old Russians’. And once we’d both gotten there we realized that neither side was all that terrible and we got along fairly well on the moon together.

BOVA: (Chuckles) My God, I started that book in 1949, and at that time it was a very different novel, and it dealt mainly with the race to get to the moon. At that time it was a cold war situation and the Russians were well ahead of us in space research and their space operations, and we had to get a crash space program going to get Americans on the moon ahead of the ‘dirty old Russians’. And once we’d both gotten there we realized that neither side was all that terrible and we got along fairly well on the moon together.

The space race is now history. In 1949 it was wild prediction. The original draft of that novel was not published because, as one publisher was kind enough to tell me, no one is going to publish a book suggesting the Russians are ahead of us in any field as long as there is a Joe McCarthy running wild. So, in a sense I guess the original version of Millennium was a victim of McCarthyism because as I think back to that draft it was pretty crudely written.

TANGENT: The weather control opportunities in Millennium that would have eventually staved off hunger and overpopulation and hence several causes for war; do you really think we’re heading in this direction?

BOVA: Yes. I think several nations are working on weather modification, certainly not full-scale control of the world’s weather, but there were weather modification trials in Laos, for example—cloud seeding operations—trying to increase the rainfall over North Vietnam and flood dikes and upset agriculture. There has been a good deal of weather modification in the United States, both by universities and government agencies, and by private operators who sell rain by the inch to farmers in the midwest.

TANGENT: I didn’t know that—

BOVA: Well, you don’t read all of my books (chuckling). I have a book called Man Changes the Weather, written for mostly junior high school age levels, but a lot of the material in it I came across quite awhile ago. But, weather modification is a serious business, and it’s at the point now where the good old United States Air Force covered up their operations in Southeast Asia. Melvin Laird, who was then Secretary of Defense, swore to Senator Pell’s investigating committee that all these reports about weather modification were pure fabrications. And then after Laird left the Pentagon, and Nixon left the White House, Laird sent a letter of apology to Pell—I believe it was Pell—saying that he had been forced to lie to the Senate for reasons of National Security. But there were cloud-seeding operations in Southeast Asia.

TANGENT: The orbiting ABM satellites in Millennium seemed to be another effective lever for peace control. Do you think, again, we will indeed have such satellites, and they will be used the way you postulate in the book?

BOVA: The basic thing in Millennium is the idea of ABM lasers as independent satellites, networks of hundreds of them in low orbit around the world, so that the nation that controls this network can protect itself from missile launches from anyplace on Earth at any time of the day or night. So, this I think is a technology that is developing.

I worked in some of the original experiments on high-powered lasers, and it makes a lot of sense to me, and to other people who have appeared in public print, to shoot down missiles with lasers, while they’re in their boost phase. And that’s going to happen around the end of this century, if not sooner.

TANGENT: Do you honestly think they’ll be used for peace?

BOVA: Well, what we’re going to use them for is what we call defense, and it’s going to be an unstabling force. Right now we have sort of a nuclear stalemate, both the United States and Russia and China, for that matter. We all have nuclear missiles that are capable of destroying most of the world, and since all three sides have them, nobody uses them. But if one side ever gets an ABM network set up, and is convinced it can limit the return punch of the other power, then it will be terribly tempted to launch a pre-emptive strike.

So, when these ABM satellites are put into orbit, politics are going to get very tricky again. There will be a renewal of the cold war tension.

TANGENT: How long do you think all this will take?

BOVA: I pegged it at 1999, but I made things simple for myself. I broke up China into little bitty pieces and made them practically useless, and brought a full-scale confrontation between the United States and Russia back into play. 1999 also has obvious dramatic reasons. It’s the end of this millennium and the beginning of a new one. The last time a millennium rolled around most intelligent Europeans were convinced the world was going to end, and they were damn near right. I think my time scale is probably pretty good. I would think in the 1990s we might see lasers in orbit.

TANGENT: It seems we always do too little, too late in terms of pollution control and many other things. Do we really have the time to save ourselves?

BOVA: Well, you know, there’s a price for everything. The slower we go on pollution control the higher the eventual price will be. The price will include the death of lots of people. But we’re just starting now to begin to be aware of the problems of pollution and the real damage that it does, not only environmental and philosophical damage, but damage to our pocketbooks. I think when we get rid of the current administration and we get the Carter administration in we’re going to see a much stronger stand by the government, and less of this palsy-walsy leniency with big industry. I’ve been convinced for a long time that to make pollution control work in this country is to make it into a profitable industry. That can be done just as Space Research and Development was done, with large scale government investments, and pretty soon you’ll find a viable pollution control industry and people will be making very nice fortunes out of it.

TANGENT: Do you think Carter will take steps in this direction?

BOVA: Yes, I expect him to. If he doesn’t I’ll be very disappointed. He has a very good record in that regard as the Governor of Georgia.

TANGENT: Before we move on is there anything else you’d like to say about Millennium?

BOVA: Well, it’s a novel I’ve been very close to for over a quarter of a century, and it took a lot to finally get it finished. I don’t think I’l lbe able to write another novel like that for another quarter of a century. But I’m already working on it.

TANGENT: What really bugs you in science fiction? What really pushes your buttons?

BOVA: Laziness, more than anything else. On the part of the writers and the readers.

TANGENT: What about editors?

BOVA: I can’t really say what editors are doing because they have to deal with not only their own management but the quality of material that is submitted to them. For example, editors like Ted White and Jim Baen, are not producing the magazines they could produce largely because they don’t have the backing of the management.

The kind of laziness I’m talking about is writers, new writers especially but older writers do it too; they keep thinking in the same old stereotype ruts. The same interstellar empire, the same stereotype problems and situations. Science fiction is an exciting arena, it’s a literature of ideas, and it’s dreadful to see not only the best writers in the field but especially the newer writer just falling into the same old pits of cliche. The newer writers should flex their muscles in different directions. It is not good enough for a young writer to ape the kind of stories he read five or ten years ago. The new writer has got to produce something that is so fresh and different that in its way is better than anything the successful, established writers are producing. A new writer has got to sing a new song, and no editor is going to publish a watered down version of Christopher Anvil or Harlan Ellison or anybody else when he can get the originals.

TANGENT: Have a lot of your stories that you’ve had to reject lately been because of this?

BOVA: Well, this has been a pretty consistent problem all the way through. We get from fifty to one hundred manuscripts a week and about 99% of them get rejected. And this is all of them, slushpile and all the rest. On the other hand, most or a very large percentage of those that go into the magazine are from brand new writers.

This is one of the reasons we instituted the John W. Campbell Award at the worldcon. It’s in sort of recognition that John, through Astounding and Analog, his major contribution to the field I think was in developing new writers. And I think that’s what an editor is in business, really, to do.

As I said before, any damn fool can publish Ernest Hemingway, or the big name writers of the day; but if an editor is really doing anything effective at all he’s discovering new writers and furthering their careers.

TANGENT: Is this all that really bothers you?

BOVA: It’s the only general thing, yes. There are all sorts of individual issues that I’d be on one side of or another, we have some lovely arguments. But that’s part of the fun of the field. I think people really only learn through argument and science fiction is one area where people have the smarts to make effective arguments and produce this clash of ideas that is both entertainment and instruction.

TANGENT: Where do you see science fiction going today, and where would you like to see it going?

BOVA: Well (chuckling), I think it’s going in all directions at once. As a publishing medium I think it’s moving into several different kinds of publishing ventures in different media. As I said, there are new magazines coming out; I think there’s a growing recognition that a large part of the potential science fiction audience is illiterate, or nearly so. You’re going to see more science fiction produced on records, tapes, film strips, comic books—

TANGENT: So they don’t have to sit down and read?

BOVA: That’s right. The thing we all hope for is that by making it easy for them to get into science fiction we can encourage them to read and get into the good material. But on the other hand, Shakespeare didn’t write his stuff to be read, he wrote it for an audience that was also illiterate. And there’s no reason why you can’t write good fiction in different media.

We have grown up in a print era, and we’re kind of prejudiced by it. Science fiction people, out of all the people in the world, should be prepared to admit that there are other ways to do it.

As far as subject matter is concerned, I’d like to see more stories coming out of the biological sciences. I think this is where the blue sky research area is right now. And except for maybe a few cloning type stories this vein hasn’t really been tapped.

TANGENT: Does any of the feminist rhetoric in science fiction bother you?

BOVA: I’m delighted that these people are expressing their opinions. I think some of these opinions they’ll retract five or ten years from now, but that’s okay. Revolutions always go this way, and I think the feminist revolution is the best thing that’s ever happened to men.

TANGENT: In which ways?

BOVA: In the way Martin Luther King expressed about the black revolution in America. That it is important for the black man to be free because this makes the white man free. You can’t have slaves without everybody being slaves.

And, if women are oppressed, if they have gripes against society—and they have legitimate gripes I think—it is high time they got it out in the open and went about solving the problems. And I don’t think anybody but the blacks will ever solve the black problem in this country, and I don’t think anybody but women will solve the problems of women. I’m delighted to see them doing it.

TANGENT: A few fans recently have voiced some dissatisfaction over the fact that it is so difficult for an artist not living in New York to break into the professional field. Is this true? What can you say about that?

BOVA: Well, first of all, writers anywhere in the United States if they want to be in the publishing business, must go to where the publishers are, and if you want to be a lumberjack it doesn’t do you any good to sit on top of Mt. Rainier in the snow. You go where the trees are.

We’ve found, over the years I’ve been editing Analog, and John found before that, that it’s just about impossible to work with an artist who can’t get into the office to discuss the story and to see all of the various problems that we have internally.

First of all, remember that what we’re talking about are illustrations—these are pictures that are drawn to illustrate stories. The story is the original material, and the artist in this case has got to draw pictures that will help the reader to visualize what’s going on. We have found, through a number of avenues, that the science fiction readers, by and large, have an excellent imagination when it comes to abstract ideas, and a very low visual imagination. They can deal with galactic-shaking events but they can’t picture them. But it is important to have illustrations that show the reader what this guy looks like, what the machinery looks like, the lay of the land. We’ve found that our readers like that, and we feel most readers do.

What we’re asking for is pretty tricky. In most of our stories we have a discussion with the illustrator and we pick out, in general, the idea that is to be gotten across in the illustration, and very frequently I will let the artist figure out what scene he wants to illustrate, or whether he wants to do something that is non-representational of the theme. Now, the game is to help the reader visualize what is going on, to give him a feeling for the tone and theme of the story, but not to reveal too much about the story. I’ve seen illustrations where readingthe story is pointless because the picture gives you the whole thing.

TANGENT: Do most of your artists read the entire piece they will illustrate?

BOVA: Yes. In fact, generally when an artist gets a story to read and comes back with his first sketches of your cover he is much more familiar with the story than I am, because he’s read it so recently and I’ve read five hundred stories in between. And he can give me very, very detailed information about the story that has completely slipped my mind.

TANGENT: Have you heard any good one’s lately, Ben?

BOVA: (Laughing) Let me think. Nothing that I didn’t tell you a few weeks ago.

TANGENT: Nothing new from Harry?

BOVA: No, Harry’s in Dublin now, and they just finished the first European Science Fiction Writer’s Conference. I talked to Gordy Dickson earlier today and he seemed to think it was a marvelous time. And he’s usually a pretty good indicator (chuckling).

TANGENT: Thanks much, Ben.

BOVA: You’re welcome, David.

The End

Ben Bova interview copyright © 1976, 2020 Dave Truesdale.

All rights reserved.

[To view the entire list of Tangent classic interviews, click here.]