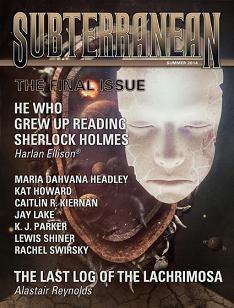

Subterranean Online, Summer 2014

Subterranean Online, Summer 2014

Reviewed by Martha Burns

Elisheba has attempted to steal a powerful relic—the Key of Shackles—and now lays dying in a demon’s arms in the depths of an Egyptian pyramid. “Pushing the Sky Away (Death of a Blasphemer)” by Caitlín R. Kiernan gives a glimpse into a world of ancient deities fighting one another and creatures who lurk in dark pyramids waiting to eat whoever might come by every millennia or so. We get very little sense of who Elisheba is, her motivation, or even what it is that the key does. In place of learning about her, we must piece together what’s happening, but without a character to care about, it is hard to have a reason to be involved with this world.

In ethics, “the problem of evil” refers to the clash between a belief in an omnipotent and benevolent deity and the fact that innocents suffer. This is why we have fiction, so that very bad people can suffer, good people can triumph, and we can have a great time while that happens. The novella “The Last Log of the Lachrimosa” by Alastair Reynolds gives us just that. A three-person crew investigates a planet after they find a stripped-down starship orbiting above. The crew lands, finds a shuttle and the diary of an officer marooned on the planet, who has left to investigate a mysterious cave. Two of the crew think it is a bad idea to go after her, if she is even still alive. Even the captain’s pet monkey thinks this is a bad idea, but the captain hopes there’s something they can sell in the cave, perhaps some abandoned tech. Captain Rasht is a bully, along with not being terrifically bright. His first officer, Lenka, is as meek as the monkey and the other crew member, Nidra, is hoping for a better assignment. Everything about this situation that one wants to happen happens. What is in the cave recalls Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness, though these monsters have a sense of responsibility one doesn’t see coming, which Nidra uses to her advantage. The story is engrossing from beginning to end, the characters are sharply drawn without unnecessary close description, we feel for the dead without any heart-twisting underhandedness, and the story leaves us with hope, as well as our desire for vengeance sated. Highly recommended.

Viola becomes a Night Doctor after a hand appears out of the night sky and reaches into her brother’s chest and crushes his heart. Viola’s tutor is Rafe, who has been a Night Doctor for some time. To be a Night Doctor, you must stitch up the tears in the universe with your own blood and the suspense involves just how much of it Viola will have to spill. “The Very Fabric” by Kat Howard is an odd little jewel with its own internal logic. It is up to the reader whether the rip in the fabric of the universe or Viola and Rafe’s attempts to stitch it up have any significance outside the story’s logic.

A man simply cannot kill his wife, who is a witch. Literally. Nor can he kill himself to be rid of her, so they travel through time and she tries to make him happy by doing exactly what he says he wants, which works as poorly for Buto, our narrator, as it does for your average O. Henry character. Narrated in a style that I’ll call “rogue Bertie Wooster,” the novella “The Things We Do For Love” by K. J. Parker is great fun and, at times, even deep in matters of love, culpability, and morality. Recommended.

A space shuttle is stranded on a windy planet. The captain has a daring plan that may (probably will) result in his death, but will also give him the opportunity to appreciate alien beauty. The pace is fast and the descriptions are evocative in “West to East” by Jay Lake, and if the reader is fine with a story whose resolution is not a standard resolution at all, but more a sense of wonder, then the reader has a treat in store.

As a result of a fever, a young girl is blinded, but is then able to see ghosts. The girl, Beate, sometimes sees deaths repeated over and over or, at other times, souls asking for recognition or help. Beate is miserable and her parents are embarrassed, so they take her to an opthamologist who believes he can cure the girl’s blindness and her parents hope that when her natural sight is restored, her infernal sight will disappear. Doctor von Hippel does restore Beate’s sight and, for a time, it seems she’s now relieved of the spirit world, but something sinister is out there in the forest huffing and puffing and trying to get in. The novella “What There Was to See” by Maria Dahvana Headley is wonderfully creepy and as the questions pile up, we wonder how Beate’s story will end. There are many fine details in this gothic tale, from the lives and afterlives of the rabbits the doctor uses to experiment on, to a dinner party in which an elderly Irish doctor recounts how he restored the eyesight of a sultan’s pet gazelle. Things comes to a crescendo when the old Irish doctor shows up again, late in the story, and fights a spirit who has been making the girl’s life a hell and then, and then, things don’t get any better and the girl gets old and dies. It is odd when you consider that the otherwise fine story leaves space for a satisfying fantastical resolution: the elderly and endearing Doctor Bigger, who is much more fun than the stuffy Doctor von Hippel, saves Beate from her phantom menace. It edges up to that ending and then doesn’t take it. I blame reality. The story takes its inspiration from the real Arthur von Hippel’s nineteenth-century experiments with corneal transplants, but falters when it tries for the same resolution history provides. We get old and die is how our stories end and this is why we want to read something else. Recommended.

In the novella “Grand Jeté (The Great Leap)” by Rachel Swirsky, a Jewish tinker’s daughter is dying, and so he makes a robot child to take her place. Swirsky uses this contemporary reimagining of the story of the golem of Prague to explore personal identity and our desire to avoid death. The robot child is an exact copy of the tinker’s daughter, Mara, up until Jakub gives the robot, Ruth, a different name. At that point, Mara and Ruth’s experiences diverge, but so slightly that we see the process of one person becoming another. In a simpler (and more simplistic) story, Ruth would be Mara had she lived, but this isn’t a simple story. Instead, Ruth is the afterlife cheated, because even though she has all of Mara’s memories, along with all of her emotions, the fact that Ruth isn’t going to die makes her a fundamentally different entity. Mara preferred DVDs of her mother’s comic ballets, whereas Ruth prefers the tragedies. The message here is that death truly is the end of personal identity, something Jakub cannot see. Swirsky gives us the breathing space to come to our own conclusions about Jakub, but what will stay with me is his utter self-absorption. This is a father who will not eat if his dying child won’t eat and we get to see how awful this is from the child’s perspective. Yet there is nothing evil or devious about Jakub. His moral failure is that he rejects the sanctity of death. Swirsky’s story ends with Ruth staying and assuming Mara’s name, yet it also paves the way for her leaving and becoming herself. I wish she’d use her healthy legs to run. Recommended.

The novella “The Black Sun” by Lewis Shiner concerns a group of five stage magicians who want to defeat Hitler. One, Adler, is an elderly German man who doesn’t want to see his country fall to a madman; one, Paco, is a Spaniard who is worried about fascism in his country; two, Gideon and Robertini, are Jewish; and one, Cora, feels compelled to fight Hitler because of a Jewish school friend’s botched nose job. One of these things is not like the other. One of the five heroes is not the same gender as the other. Sadly, this multiple problematic oddity comes very early in the story, so Shiner hasn’t won us over yet with the strengths of the story, and there are many. The plan to defeat Hitler by exploiting his interest in the occult is inventive and each of the five are able to use their personal strengths, one of which is to be attractive even at thirty eight (yes, Shiner says this). Now, the point isn’t that these tics involving the lead female character are offensive, which they are. The point is that they are getting in the way of a caper that could have been much more fun than it is, though it isn’t clear why we need another story about defeating Hitler and it isn’t, in the end, clear what we’re to take away from the story.

“He Who Grew Up Reading Sherlock Holmes” by Harlan Ellison provides a series of seemingly disconnected events, some of which, in the end, come together, much as they do when Sherlock Holmes unlocks a puzzle by piecing together things most would ignore. The difference is that in a Sherlock Holmes story, we are introduced to a puzzle we want to solve, something simple like a death or a case of a missing person, and are astounded at the way Holmes comes to his solution, whereas in Ellison’s story, after an initial engaging narrative sequence, we get disconnected events and the puzzle is how they fit together. One approach is much more fun than the other.

Sadly, this is the final issue of Subterranean Online.