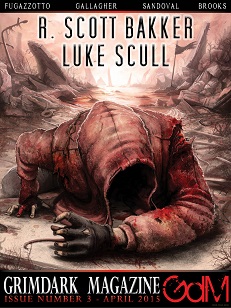

Grimdark Magazine #3, April 2015

Grimdark Magazine #3, April 2015

Review by Harlen Bayha

In “A Recipe for Corpse Oil” by Siobhan Gallagher, Tavin, our rapscallion protagonist, goes on a fetch quest for potion ingredients, but what makes the story truly bizarre and compelling is the way he goes about it, and the objects of his search. So as to hint and not spoil too much, I’ll just say that the acquisition of the ingredients involves an axe, stealth, and copious amounts of alcohol. Tavin takes his job seriously until it becomes a little too hard, and in the end he decides to try to find a substitute for his product to meet quota.

So many messages in a tight little package here: this story could be a veiled allegory for the 2008 subprime housing meltdown, or a warning to enterprises that unethical employees simply aren’t trustworthy. Or maybe it’s just a fun story about hacking people up for business purposes. It’s a fine intro to an enjoyable third edition.

In “The King Beneath the Waves,” Peter Fugazzotto batters the lives of six Viking clansmen and two slaves against the reefs of hunger, greed, and anger. The eight abandoned their sinking ship in a storm and struggled back to shore, where they find little food and a power vacuum that everyone with a weapon wants to fill. Werting, the youngest, and one of two slaves, imagines freedom and vengeance against the Vikings who dragged him from his home, but resigns himself to mere dreams as he forages for mussels for others to eat and serves as demanded.

As they walk, they discover an old ship exposed by the tide. Tensions rise as they recover a hoard of mead, weapons, and armor. When Werting discovers a crown, a symbol of leadership and wealth the clansmen jealously covet, it’s only a matter of time until the slow-burn disaster culminates in a bloody finish. There’s not much fantasy in this story, but there sure is a lot of grim, and a lot of dark, as promised.

Kelly Sandoval’s “All the Lovely Brides” dissects a brutal covenant between a godlike Lord and the Brides who serve him. Like so many gods, this Lord requires sacrifice, and the Bride gives her life force to him over a span of just a few years. As she dwindles, the Lord becomes hungry for more, and demands a new Bride from his priests. To consecrate the marriage, the new Bride slits the throat of the old Bride in preparation for the wedding vows. In exchange, the Lord keeps the land fecund and prosperous.

The story centers on Lydra, the current Bride, who has grown into a callous, pragmatic woman since her marriage. As she coaches her successor in the loveless ways of their Lord and how to properly slit a throat, the ending seems foregone. Someone must die.

It’s easy to sit back and judge a character like Lydra until you’ve walked down the aisle in her shoes. Her decision at the end wasn’t likely even that hard for her, given her choices, and its repercussions will be felt by her people forever. Maybe they deserved this particular Bride after all.

This story can also serve as a deeper metaphor on various levels, if one chooses to read it that way. The Bride here could represent women, particularly women of the third world, where men dominate women with rape and brutality, preventing unmolested access to education and work, and literally draining the life out of them. The women, like the Bride, have no one to turn to but each other, and accept their situations because they must. Their communities fail to help because they believe they have no other options. Or the metaphor might echo first and third world relations in general. The Lord of the tale feels like a first world observer, cut off from the local community, caring about it only because it is a source of power and sustenance. The first world also returns some semblance of prosperity in the form of money, services, medicine, and education via humanitarian organizations, true, but the flipside is the low-cost and slave labor that these third world nations provide while, again, draining the life from the local populace.

Telling the story from the perspective of a privileged woman faced with no good options makes Lydra’s aggressive choice feel logical and consistent within the framework of her world, and shines the light of understanding on many of the similar choices made by people living in dire circumstances that first world observers find strange because they are so far outside of our frames of reference.

“The Knife of Many Hands, Part II” by R. Scott Bakker breaks the flow of the other original stories in this issue and presents what feels like a disconnected chapter in a short novel. Heavily written, with fat words and references to a wide, complex world tossed about like gobs of flesh in an abattoir, it made for a difficult introduction to the world of Eryelk the generic barbarian.

It felt like the story spent the first half of Part II recapping events from Part I and the latter half boffing Queen Sumiloam. In the end, a series of psychological perspective-shifts made the ending difficult to grasp, and seemed to reveal that perhaps Eryelk had no control at all in this story, which also seemed to leave the needs and motives of the true actors hidden and vague.

Harlen Bayha stands alone in a field of tall dry grass, wearing only a football helmet and flailing a baseball bat at empty air, screaming. When he calms down, he sometimes uses his words to make fancy books.