“A Ring to Rule Them All” by Luke Scull

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

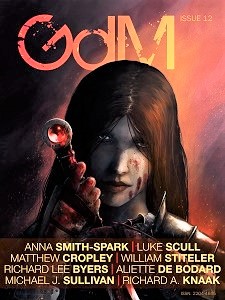

The twelfth issue of Grimdark offers interviews, articles, and three original short stories. The last one I reviewed was Issue #4, and it’s good to see it still with us. This one may have but three stories, but if you like grimdark … read it.

William Stiteler’s “Peddler” opens on a horse-cart driver who observes unexcitedly while bystanders he passes are attacked and eaten by monsters. The death as business-as-usual is a great grim open. And when we finally see Stiteler’s concept for “Peddler” it is dark-fantasy gold: a world in which creatures from another dimension—who’ve developed a taste for human—craft summoning spells from words unlucky speakers inadvertently utter, to their short-lived dismay. Stiteler employs this premise toward a glorious world-building purpose: fear to speak devastates culture, kills communities, wreaks havoc on the psyche … and undermines the invaders’ access to the world. Stiteler’s take on a grimdark snake-oil salesman is as awful and glorious as you’d hope. This is why we have grimdark.

Luke Scull’s “A Ring to Rule Them All” is a pre-execution jailbreak (wicker-cage-break?) set in a dark fantasy world. It follows several men who each scorn the poor oath-keeping of the last-depicted character. The men, though each somewhat at odds with the other, are united in being significantly motivated by offscreen women. There’s no on-screen magic; depicted conflicts feature spears, axes, and threats of physical force. The story may be recommended to readers interested in a Viking aesthetic and barbarian warriors. The decisions that resolve the conflicts—revolving around the promises actors choose to keep, or broken promises they choose to avenge—seem low-stakes compared to the immediate physical danger, almost excuses for practical action. It might be more interesting if the climactic decision were more difficult for at least one of the characters. Yet it’s a decision that fits: the characters whose decisions shape the climax decide to prioritize their off-screen obligations over the concerns that would escalate their on-screen conflict. The choice to write an averted fight for the story’s (anti?) climax is brave, and its success can’t be answered for every reader in a review.

Although presented in third person, Anna Smith-Spark’s “Red Glass” is stream-of-consciousness from the point of view of a resident of a city overrun by an unstoppable warrior horde. Far too zoomed in to give any perspective why the horde was set in motion or the goals of its leader(s), the piece shows a barmaid in her creatively-adopted new career as a member of the horde: from horror through illness to enthusiastic advocate. The reader can decide whether elements of Stockholm Syndrome or PTSD explain some of her actions—the work itself presents no introspection. The only disclosed motive is survival. The question raised about the earnestness of the horde’s newest member’s support is interesting: her participation was her ticket out of a gruesome murder, sure, but does she—like Orwell’s Winston Smith in 1984—actually come to believe? The piece frequently disdains grammar for fragments; like adjacent ideas, they mimic the process of thoughts proceeding past. This forces the reader to supply the connective tissue, get into the mind that produces the thoughts words, and sucks the reader into the stream-of-consciousness to feel the horrible world all the more directly. The piece isn’t about glorious purpose, but a personal experience on the underside of the horde’s heavy boot. The personal cost of the character’s survival is dark and terrible and almost certainly what Smith-Spark aimed for.

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.

Grimdark #12, July 2017

Grimdark #12, July 2017