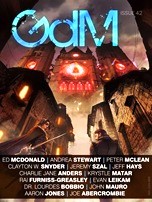

“Beneath Green Skies, We Devour” by Ed McDonald

“A Love Like Many Bruises” by Jeremy Szal

“Palm Strike’s Last Case” by Charlie Jane Anders

“The Brackwater Son” by Andrea Stewart

“Only the Broken” by Clayton Snyder

“Born Pious” by Peter McLean

Reviewed by Seraph

I’ll admit this opportunity has taught me how little I understood about what this particular genre has evolved into, when I started these reviews. I’m pretty familiar with some well-known world settings that are credited in a lot of circles for originating (at the very least) the name of the genre, and for popularizing it in the public eye. What I found in this issue’s stories sometimes didn’t fit that mold, so of course I had to take the deep dive into what grimdark fantasy really consists of. By the end, I may have been more confused as to what is and is not within the genre than at the start, but all the same walked away with an understanding that in a lot of ways, that very inconsistency is the point. Nihilism and brutality in outlandish settings are characteristic of the genre, but at its heart… it is a rebellion against hope and all that is considered good. It is a rejection of fairy tales and happy endings, and there are myriad forms in which that can be expressed. In that light, this issue presents six works of hopeless persistence in the face of inescapable doom, each showcasing in its own different fashion how futile it all really is.

“Beneath Green Skies, We Devour” by Ed McDonald

One of my favorite quotes goes something like “All of this has happened before, and all of it will happen again.” Like any good quote, it can be taken and applied in a number of ways, but in most of those it is an expression of the futility of trying to effect change. In almost every case, the odds are overwhelming… but the real problem is how people just can’t seem to help themselves from doing all manner of selfish and destructive things in the name of what should be positives, like love or hope. Farlan Ryfe’s whole world is ending. Yes, yes, the world is actually ending, but his world is ending. The love of his life, the wife of his friend, was finally his, until his friend came back from the dead. Never mind that this woman is brilliant, and that she has come up with a miraculous machine to help them all escape the end of the world. It’s unclear exactly what happened, but he comes back from a mission proclaiming the certain death of the husband, who re-appears once again not-dead just in time for Ryfe to drag her through the gateway. Of all the stories in this issue, this one matched most closely to what I expected from a grim-dark fantasy story. The cyclical destruction never ends, and it could… but it won’t.

“A Love Like Many Bruises” by Jeremy Szal

Lorenzo has an obsession, and like any good obsession, he is relentless in his pursuit of it. No cost is too high. The Daasi are just misunderstood, you see. They killed untold numbers of humans before they were defeated, but if humans had just stopped and talked with them then of course there could have been peace. Even as the captured alien treats him with utter contempt, he has lost too much to stop now. If only the other humans could just understand like Lorenzo does, if only his fiancée would be more understanding and not beg him to stop… I probably don’t need to clarify this, but it doesn’t go well. This is appropriate for the genre, but it just spectacularly doesn’t go well at all. Pity the fool who romanticizes an enemy who never stopped being an enemy. Pity the fool who tries to “save” an enemy whose hatred overflows, who views you as little more than an insect. But most of all, pity the fool who dooms his entire people for the sake of his stubborn, unrelenting conviction that his “reality” is the true one, in defiance of every piece of evidence and rational thought in existence screaming at him. It is an unbearably timely message, but one that is constantly ignored by the fictional and the living.

“Palm Strike’s Last Case” by Charlie Jane Anders

This story probably hit upon one of my own fascinations the most closely. At which point do the pursuit of vengeance and the hero’s journey come crashing together? Even if history judges you the hero and not the villain, does the good you eventually achieve moderate the suffering you inflicted, even if you could argue that your enemies were evil and had it coming? One of the hallmarks of the genre is that the “good guys” are more like the less-bad guys, and the lone warrior standing against them all has to be unflinchingly brutal to achieve any semblance of justice. Palm Strike is no exception. He lost someone that meant more than the whole world to him, to senseless and cyclical violence. In perfect fashion he returns that violence dozens of times over, but to the end the question remains. After a pursuit that stretches across space and even time via the miracles of cryo-sleep and interplanetary ships, the weary and somewhat super-powered vigilante still cannot escape the futility of human nature. Earth has long since fallen to ruin and although humanity has reached all the way across the stars to his new home of Argus City, somehow people haven’t changed a bit in all of that time. Yes, the corrupt are finally vanquished and forced to submit… but in the end, after all is done and the bodies dropped by both sides are cold, can anything erase the sheer damage that he did along the way? Can that damage justify his actions, which quite profoundly do good for his new home so far from his old one? The author answered this question in the most perfectly grimdark way possible: by not answering it at all.

“The Brackwater Son” by Andrea Stewart

Of the six stories in the issue, this is the one I am the most unsure of. It is just all around painful to read, and I’d go so far as torturous, even. It is without any doubt grim, but it is missing something. The story pulls you in almost too well, and the pain of the mother whose child hates her in spite of every sacrifice she has made is almost visceral. There are fantasy notes present, though the mythological elements like merfolk and mysticism feel more like window dressing. If I could put my doubts into words, it would be that one of the hallmarks of grimdark fantasy (as best as I newly understand) is making a point by means of fantastical, completely over-the-top scenarios and unbelievable odds. It is precisely the absurdity and the un-realism that hammer the message home. This story felt entirely too… real. Which is an utterly bizarre thing to criticize in normal cases, but despite the fantasy trappings it feels very much as though this is a mother you could meet in real life. I struggled to find any way to read this that wasn’t the story of an endlessly-sacrificing mother hated by a child who she stubbornly refuses to give up on. I just can’t figure if that makes this a complete masterpiece in spite of the limitations of the genre, or if it missed the mark because of those same limitations. All I can do is compliment the author on such an engaging piece, and to wonder at it making me so thoroughly question if I understand the bounds of this genre.

“Only the Broken” by Clayton Snyder

One of the things I am coming to appreciate as the greatest strength of grimdark fantasy is the ability to take familiar concepts and settings, and to twist them into something horrific. Or, in some cases, something even more horrific than an originally terrifying scenario. Futuristic soldiers surrounded by incredibly advanced technology that is somehow insufficient to overcome the odds? Check. Enemies who inexplicably overcome every tactic and outplay your every counter? You got it. But the twist at the end, in this one while not particularly a new one or even a subtle one, really just takes it to an entirely different level. There are few better ways to communicate just how truly bad it all is than “well, we tried our best, but this soldier really just isn’t prepared yet for how bad it is out there.” After, mind you, it all goes to hell. Nothing says hopeless nihilism like a horrific death just being the beginning of endless terrors to come, and you aren’t even out of training yet.

“Born Pious” by Peter McLean

The complexity of this story is rather skillfully understated, and I have nothing negative to say about the quality of the story. It is well written, it is engaging and many of the elements are so familiar as to be classic… for an organized crime/spy thriller set in a gritty fantasy world. The Piety brothers and their band of Pious Men lived in the filth, but that didn’t mean that everyone had to suffer. There’s a certain perverse nobility to the brothers’ violent benevolence. But of course the agents of the Crown would take notice, and of course that one favor that they ask would turn into a lifetime of doing the Crown’s work… the kind that it could never admit to ordering. I struggled to find the nihilistic aspects within the story, but if you hadn’t told me it was supposed to be grimdark specifically, I’d not have thought twice about it. So all around it was quite well-done, and was plenty enjoyable to read.

Grimdark

Grimdark