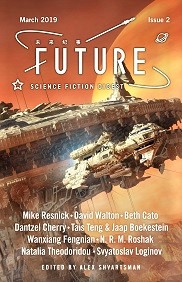

Future Science Fiction Digest #2, March 2019

Future Science Fiction Digest #2, March 2019

“Tideline Treasures, or Growing up along the Mile-High Dyke” by Tais Teng and Jaap Boekestein

Reviewed by Robert L Turner III

This issue is strongly international in flavor with stories from multiple countries and languages. Additionally, the entries are unified by the attempt to portray a larger vision of the universe.

Tais Teng and Jaap Boekestein kick off the issue with the piece “Tideline Treasures, or Growing up along the Mile-High Dyke.” This is part of a larger shared universe created by the two and described as “optimistic climate fiction.” It is set in a distant future where climate change, war, and bio-engineering have created multiple sentient species and changed humanity drastically. In it, Hanneke and Gerben, two young beachcombers, are summoned to the higher levels of the Dike, the mile high wall outside of what is currently Amsterdam. They have unexpectedly found seagull feathers even though that species was thought extinct. The plot from here on is straightforward with different factions desiring to capture samples from the newfound nest. The story is solid and well-paced, but it is the world that shines. The authors present enough information to interest the reader in the larger world, but do not overplay their hand and just give the reader an information dump. The ending is predictable, but satisfying and the story makes the reader want to see more of this world.

“The Roost of Ash and Fire” by David Walton continues the avian theme with the story of an astronomer who discovers the impending impact of a giant asteroid. What makes this story so fascinating is how Walton creates his characters and then makes their choices seem so obvious and logical. A lesser writer with exactly the same material would have ended up with something trite. Walton manages to avoid some fairly challenging traps and keep the aliens alien while making the reader care for them. The final twist is very clever and blends melancholy with hope admirably.

“The Lord of Rivers” by Wanxiang Fengnian, translated by Nathan Faries is another piece with big ideas and a large scope. Melding the heat death of the universe and the near future, the story is focused on the growth of an AI and its attempt to understand humanity. While well written and interesting, I feel that there are cultural nuances lost in the translation. This is not a critique of Faries work, he does a solid job. However, I suspect that the cultural realities of China create elements that do not translate well to an English speaking audience. This is most notable in the finale where the conclusion lacks the punch that I suspect it would have to a Chinese reader. That said, the work is solid and I believe those who are more informed of Chinese culture would get more out of it than I.

Dantzel Cherry takes the issue in a new direction with “No Body Enough.” It’s set in a future where humans create “collectives,” mind-melded groups that have a “primary” personality but share a blended mind. The narrator loses a body in a poker game and has to accept a government sponsored personality/body to make ends meet. Once the new member joins the collective, they learn of their mutual needs and share in their mutual mental struggles. The concept is very interesting, but the psychology of the broken collective leaves something to be desired. I don’t feel that the reader is given enough reason to empathize well with the narrator and the semi-hopeful ending didn’t ring true to me. I really like the world building, but the story, stripped of the exotic setting, feels trite. The symbolic representation of depression and isolation doesn’t quite hold together.

“An Actual Fish” by Natalia Theodoridou suffers from many of the failings of the previous story. The Adam, an early model android, wants a fish, which represents attaining humanity. When he is offered one in exchange for a forbidden activity: “a sin,” he must decide if the exchange is worthwhile. The story is quite short and looking at the symbolism, you can argue that the fish represents the soul. Digging deeper, I would argue that the story is structured around Christian symbolism and that the fish not just a soul, but that the ending is also tied to the deal made between Jacob and Esau. The problem is that the story does not connect the threads. The conclusion was solid, but the nature of the writing is too surrealistic to make the story work.

Set in a steampunk universe where the lunar mining team has been stranded due to an eruption of the Yellowstone super volcano, “The Peculiar Gravity of Home” by Beth Cato mixes an old lady with cats, a desperate attempt to make it back to Earth, suffragette sentiments, and a question of where we belong. Despite the fact that the elements are difficult to reconcile, the author does a reasonable job of making the components fit. Unfortunately, the tone doesn’t aid the story and so while entertaining, it is also forgettable.

“The Zest for Life” by N. R. M. Roshak is an odd, absurdist, entry. The premise is that aliens arrived on Earth and, after refusing to communicate with humanity, leave behind a recipe for salad dressing carved onto various mountain faces. The narrator discovers that the dressing makes plastic edible and very tasty. Furthermore, it tastes better the longer it has been in ocean water. From there the story takes the odd, but logical path that humanity, addicted to the taste, cleans the oceans in an attempt to get at all that delicious plastic. The work is too serious to be a light comic piece, and too strange to work as environmental allegory.

Mike Resnick is a legend in the field and has a gift of making the common seem mythic. Sadly, “The Token” is a much more narrowly tailored piece. A soldier who will soon be sent to war buys a replica android to keep his fiancé company while he’s gone. From this setup the story moves in a very predictable fashion where the girl and her companion android become inseparable. When the soldier returns early due to an injury, Trina and Rob (the android) must find a way to help everyone find happiness. The story feels very much like a throwback to Golden Age SF with even the activities and dialogue seemingly coming out of the early 40s. While the story is quite serviceable, it feels dated.

The final entry comes from Russia. “To Save a Human” by Svyatoslav Loginov and translated by Max Hrabrov is the story of Mowgli, a human who was raised by the Amma, a hybrid creature that serves the role of a wolf in the story. Mowgli lives in the forest and swamp created by the emitter, a traffic router for FTL in the galaxy. When a human accidentally crashes into the swamp, the powers that be send a ranger, a cyborg that is much more typical of current humanity than Mowgli, who cannot accept cybernetic implants, to retrieve the crash survivor. From here the plot echoes what you might find in Kipling. The ranger represents technology, progress and science, while Mowgli represents local knowledge and attunement to nature. When the ranger fails in its task, Mowgli decides to try for the rescue. The world building is both unique and self-consistent, although often strange. It works well as a port from the exotic world of The Jungle Book. The end fits well within the milieu and is satisfying if a little predictable.

As a coda, this new publication is ambitious and very wide in scope. Even when some of the stories failed, they generally tried to do big things and to explore big ideas. I personally hope for the success of the magazine.

Robert Turner is a professor and long term SF reader.