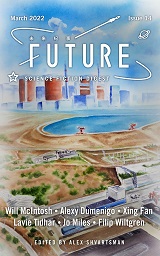

Future Science Fiction Digest #14, March 2022

Future Science Fiction Digest #14, March 2022

“A Friend on the Inside” by Will McIntosh

“Four-Letter Word” by Alexy Dumenigo, trans. by Toshiya Kamei

“Rat’s Tongue” by Xing Fan, trans. by Judith Huang

“Vagrants” by Lavie Tidhar

“The Sweetness of Berries and Wine” by Jo Miles

“Paean for a Branch Ghost” by Filip Wiltgren

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

From this issue of Future Science Fiction Digest, Tangent reviews six new pieces. The forward notes the editor’s difficulty finalizing the issue while his hometown in Ukraine braced for an invasion by what was reckoned the second most powerful military on the planet at the order of a dictator. In the face of this, it’s worth noting the editor’s stated commitment to increasing access to SF writers whose lives and countries are upended by brutal oppressors irrespective of the locations of the borders around them or the identity of the brutal dictator seeking to silence their art. Ordinarily this reviewer considers a collection of short stories worthwhile if a third of its contents are solid stories; Shvartsman’s selections knock this volume into another league, however, with solid stories overwhelming the issue. Fans of fiction set in the future should add Issue 14 of Future Science Fiction Digest to their shopping lists.

Will McIntosh’s dismal-near-future “A Friend on the Inside” is narrated by a girl trying to hack her Yonkers high school network in the hope of spoofing a student account balance so she can afford lunch. Beautifully bleak. Fun take on the Cyberpunk trope of discovering a “ghost in the machine.” Invites thought on worker’s rights for artificially intelligent and other not-traditionally-alive beings. Recommended.

Translated by Toshiya Kamei, Alexy Dumenigo’s “Four-Letter Word” is a first-person recollection set in a dismal future wherein technology allows one to do with ease what Douglas Adams’ Zaphod Beeblebrox did so clumsily and with such difficulty in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and remove inconvenient memories from one’s own mind. And with cybernetic enhancements, dogs can carry on the kind of conversation viewers loved in Pixar’s Up!. The story is filled with details consistent with the SF elements it depicts, revealing a sad life in a dark world full of depressing compromise. In such a dismal world that people have their brains changed to tolerate their miserable lives rather than working to improve their situations, it’s an unexpected pleasure to find an upbeat, hopeful story about triumph of the heart. Outstanding.

Translated by Judith Huang, Xing Fan’s “Rat’s Tongue” presents a science fiction set in a vast dictatorship that embraces numerous worlds and varied peoples. It opens on an imperial officer charged with collecting ingredients for the emperor’s far-reaching appetites. As a person who has survived government-sponsored pogroms against foreigners such as himself, the officer understands that he holds his position, and his liberty, solely at a dictator’s whim. When the officer’s ingredient hunt brings him to a prison planet from which no exiled foreigner has ever been freed, “Rat’s Tongue” conveys the isolation of outsiders, the alienation of the oppressed, the constant threat facing every subject of a tyrant’s rule, and the unavoidable fact that anyone with a shred of humanity will be forced to oppose in some fashion or another dictators who demand compliance without offering justice. “Rat’s Tongue” gets good marks for alien aliens: they don’t come off as people in rubber masks, but have some good weird traits that make them different. The discovery of aliens offers both a new front for expanding oppression and an SF opportunity to solve the story problem. “Rat’s Tongue” depicts several solutions to characters’ oppression: two humans offer destructive solutions (one to ameliorate the emperor’s harm, and one to strike him down), while an alien, apparently possessed of greater humanity, delivers gradual reform at great personal cost. The conclusion seems to urge solutions to oppression motivated by loftier motives than mere hate, which “Rat’s Tongue” argues is real poison.

The conclusion of “Rat’s Tongue” bears examination, however. The gorgeous-looking movie Hero (filmed in China with government permission and an estimated 18,000 active-duty Chinese soldier extras) carefully laid the groundwork for a vengeance-and-liberation climax which it undermined at the last moment by the protagonist’s sacrifice to save the movie’s tyrant. Similarly, “Rat’s Tongue” comes within a hair’s breadth of delivering justice and freedom only to have its tyrant rescued at the last minute by a nameless outlander. This volume’s editor, Alex Shvartsman, just published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction his English translation of “The Living Furniture” by the Odessa-born Russian Yefim Zozula, whose author lived through the rise of Stalin, whose censors required Zozula to publish only works tolerable to the dictatorship; “The Living Furniture” both pretends to complain about a non-Soviet government and keeps its climax offscreen where censors won’t actually read about the moment of a tyrant’s defeat and fear the story might give readers ideas. The conclusion of “Rat’s Tongue” feels like it offers a similar hidden complexity. Like Zozula, its author lives under a dictatorship in which advocating political reform is unsafe; “Rat’s Tongue” was published under watchful censors whose regime boasts brutalities ranging from imprisoning intellectuals to genocide against minorities. Since the author could not have felt free to write any ending he liked, and knew censors would never allow publication of a story criticizing the government or celebrating reform-driven revolt, one wonders if he may have felt compelled to write an ending in which the story’s despot lives peacefully until he dies of old age. Readers who’ve suffered losses under the boot of one dictator or another themselves, may find the conclusion unsatisfactory without the background that the author may not have been free to write his preferred solution to the story problem. Yet the author doesn’t celebrate tyranny, and makes no excuses for it; unlike Hero, which argues unity is more important than freedom, “Rat’s Tongue” suggests an SF scheme to induce the emperor to make life better for his subjects by conditioning him against a lifelong habit of living with constant hatred. Xing offers three solutions, championed by different characters: managing the tyrant’s appetites to ameliorate the suffering as his rule embraces aliens, assassinating the tyrant with an unexpectedly delicious SF just-desserts strike, and rescuing the emperor from death while nudging him in his final years away from hate. Although the author depicts the tyrant seemingly redeemed, he plainly shows despotic rule is so brittle as to depend on the charity of strangers for its survival in the face of rough justice at the hands of aggrieved victims. “Rat’s Tongue” evidences comprehension of life under the rule of a brutal dictator–-the powerlessness, the frustration, the constant risk of new oppression at a whim. To have penned a conclusion in which a revolt successfully liberates a people from tyranny would have been unsafe, and its publication impossible; the story’s delivered conclusion may represent an argument that taking the long view to ameliorate suffering at scale is more important than immediate vengeance, or it may represent a game directed at censors who may see the tyrant living happily ever after and overlook the story’s argument that the dictator is an evil bastard whose subjects have the cleverness and patience to end him and it will take aliens from another planet to save his miserable life. Perhaps it’s a philosophical statement lionizing sacrifice, or a comment against obvious overt action against tyrants in preference to schemes that leave little room for reprisal. Given the challenges posed by censors, this piece really bears thought and its conclusion bears examination. There could be a lot of right answers here, just not the emperor’s.

Lavie Tidhar’s short story “Vagrants” is a third-person account set in a grungy future on an old space station populated with tired, jaded humans and robots who long ago burned off their excitement about adventure in space. Although its 2,000 words don’t seem to set forth a story problem or a solution, “Vagrants” is engaging and effective as a vignette depicting a fatalistic world soaked in despair and lost opportunity. If you want to inhabit a dismal future for a little while, “Vagrants” provides an express ticket.

Jo Miles opens “The Sweetness of Berries and Wine” in close third person on a space station where the main character, who wants to prepare for her young daughter the holiday meal she herself knew as a child, suffers anxiety over an unavailable ingredient. Grandma comes to the videoteleconferenced rescue, likening the situation to the privations of ancestors whose flight through the desert gave rise to some of the very recipes creating challenges in space. Thus all that is new is old, even the need to adapt recipes. The adversity arising from life on a space station with limited ingredient availability does not amount to conflict with a villain; grandmotherly advice and reassurance enshroud the reader in an eleven-hundred-word warm blanket. Comfy. “The Sweetness of Berries and Wine” may appeal in particular to readers whose family structures might have faced legal barriers a generation ago, but who want to enjoy ancient traditions: this feel-good short piece promises tradition is there for you, and Grandma’s love, too.

Filip Wiltgren’s science fiction short story “Paean for a Branch Ghost” is a third-person heist whose mastermind orders her crew to infiltrate at exorbitant cost a timeline branch so distant the crew’s members scarcely believe it’s feasible. It’s difficult to discuss the story without spoiling revelations that benefit the reading experience, but the varied backgrounds of the crew, last-minute plan changes, hidden agendas, deceptions, and plot twists definitely establish this story as a fully-realized heist. The rules of time-travel physics and the project’s limited resources give a decidedly science fiction feel to a plot that in careless hands might have become a time travel fantasy, but restrictions imposed by time-travel physics shape and constrain the decisions made in the story climax so inescapably that “Paean for a Branch Ghost” is unquestionably science fiction. Anyone who’s raged against the injustice, cruelty, and helplessness found in records of historical atrocities will feel satisfaction in the turns the story takes, and appreciate the sacrifice required to attain the protagonist’s objective. Sacrifice feels appropriate to the subject’s gravity, and a necessary price for the victory for humanity it delivers. “Paean for a Branch Ghost” is a well executed example of its genres. More importantly, it’s an enjoyable read with a solid climax perfectly suited both to its heist and science fiction plots and to the subject matter of its story. Highly recommended.

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.