Reviewed by Stevie Barry

An issue inspired by the stories of H.G. Wells, with stories ranging from the dramatic to the comedic. Some of them I found fantastic, but a couple missed the mark.

Shannon Fay‘s “Colossus” is told from the perspective of the titular machine. It was built in Bletchley, England, in 1943, and was the first programmable computer in the world, designed to crack enemy codes. Over time, it notices that it’s fed less and less information, and it wonders if the war has been lost, if there are too few humans left to run it. Decades after the end of World War II, it’s still convinced there is always more to do, more work to be done so that the humans might survive.

I found this story surprisingly heartbreaking. I wouldn’t have thought I could have empathy for a machine, but this one spins on, totally unaware that it’s become a museum piece. It reminded me of an elderly person with Alzheimer’s, reliving their glory days with little idea of how the world around them has changed. And yet I also thought it was sweet, because in its eyes it will forever be needed.

“Beneath a Cinder Sun,” by Gordon Cash, is the story of a child named Patrick, who borrows a cassette recorder from his parents so they might hear the story his “imaginary friend” told him. To their surprise, the friend isn’t so imaginary after all: it tells the story of its people’s voyages through space, and of how they manipulated planets’ suns to get the resources they needed from each world.

I thought this one was bittersweet, but far too short for the concepts it presents. It felt like it ought to be a segment of a longer story, not like something self-contained.

“Burning Men,” by Samuel Marzioli, is an extremely unsettling tale about a far-future dystopian society. It’s told from the perspective of George, a government worker who finds and incinerates the impoverished and unemployed, poverty being a crime worthy of death. His partner, Thomas, enjoys the work they do, but George is haunted by vague fears of a vengeful God, sickened by the work that he does but unwilling to quit for fear of being burned himself.

This one disturbed me deeply. What the Burners do is regarded as just another job, a kind of slogging government work that’s feared and hated by the masses. The descriptions of the charred human remains were a little too good for my comfort, but they made the story that much more effective. It’s fantastically well-done.

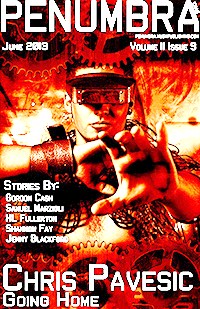

In “Going Home,” by Chris Pavesic, two travelers from the future have gone back in time to study what to them is a very distant past. The time period itself isn’t stated, but the daguerreotypes, oil lamps, and trains would suggest the early nineteenth century. It’s almost time for both to return to the future, but one of them would much rather stay where he is, preferring the hardships of the past to the sterility of his own time.

Though stories of time-travel are common, this one had a twist that lifted it a little above the norm: the fact that the travelers take over the bodies of people already existing, rather than physically going to be past. Unfortunately, the ending was rather predictable.

“Target Audience,” by H.L. Fullerton, takes place in a future where advertising has reached a new level, in the form of “hypes” whispered into a consumer’s ear. They’re tailored to a person’s age, and as a result, society is filled with people desperate to stay young enough to hear certain hypes. The main character is Adave, a woman who was instrumental in creating the hypes, and who is depressed that she’s approaching fifty and can no longer hear many of them. Now that her creation is backfiring on her, she starts thinking about what to do about it.

This one made me laugh a little, because it’s so plausible. Advertising is growing more and more invasive by the year, and what Adave created is a logical next step. The consumerism in the story is an exaggeration of our current society, but not so exaggerated as to seem unbelievable.

In “New Miracle Celebrity Weight Loss Diet,” by Jenny Blackford, a teenage girl is obsessed with losing three pounds, despite the fact that she’s already quite slim. Her friend’s aunt, who hears her complaining, gives her some “traditional Chinese medicine” that grants the girl’s wish a little more literally than she would probably like.

This is a classic “Be careful what you wish for” scenario, with a modern, funny twist. In spite of the disastrous consequences of the “medicine” the girl takes, she’s still horrified by the idea of gaining any weight. It’s played for humor rather than drama, and the ending had me laughing.