Reviewed by Matthew Nadelhaft and Dave Truesdale

May’s issue of Penumbra, with the theme of oceans, opens strongly with Lane Robbins’ “The Whale’s Way,” a tale of the future in which ecological catastrophe has given rise to massive underwater cities (habitats). Nerie is a scientist in an unnamed habitat being evacuated because of dangerous local sea changes. Even as the habitat’s population is bustled into submarines for relocation onto the newly-habitable world of land and space, Nerie is meeting with a group planning not to go. To them, the land is alien, and space even more so. The sea is their home, regardless of the danger it poses, and they struggle not only to make a life there in the wake of evacuation but to assert their right to remain. It’s a well-written story that makes a strong case for the culturally-created nature of “naturalness,” the ability of humans to feel a sense of homeness, of belonging, wherever they live.

“The Hurricane Cavalry,” by Lindsey Duncan, by contrast, describes the battle of a community on the banks of the sea to preserve itself against the ocean’s encroachment. The story is cunningly written as a fantasy battle between the forces of the earth, including treants and golems, against the selkies, merfolk and sirens of the deep. Unfortunately, there is nothing more to this story than the battle, and despite the clever allegorical depiction of a hurricane as an actual, fantastical combat between the forces of earth and sea I needed more. With no actual storyline, this brief piece was swamped by imagery for the sake of imagery.

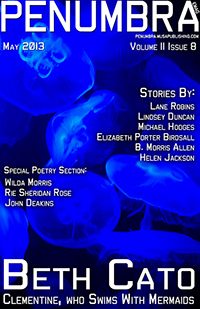

In “Clementine, Who Swims with Mermaids,” Beth Cato has opted for a simple, colloquial style, as befitting a story narrated by a young child. Donovan is at the beach making a sand castle while his sister talks about mermaids and their mother flirts. When his sister disappears, Donovan tells the police she went to play with the mermaids. The rest of the story details Donovan’s experiences following the disappearance, as he holds firm to the belief that his sister is happily living with mermaids while adults console and counsel him on his loss. The story is well-written, excepting a few jarring lines. Likewise, it is moving and evocative – although I was slightly disappointed by the ending, which wrapped things up rather too neatly for me. I’d have preferred a note of ambiguity and loss.

“Uncommon Ally” by Michael Hodges, another very short piece, opens with a powerful depiction of an Earth ruined by “invasive species” from space ravaging the oceans. While it isn’t a very believable scenario, the atmosphere is striking and reminded me of John Wyndham. Like “The Hurricane Cavalry,” though, this story is rather short on plot, and consists mostly of the main character, Chike, watching a great white shark battling the alien creatures. It’s a rhapsody on the famed predator and, while I certainly don’t object to a rhapsody on sharks (I’m a big fan of them, too), I’d rather read one in a different kind of writing.

Elizabeth Porter Birdsall takes a different look at sea creatures in “Convergent Motion.” “The creature,” Birdsall’s protagonist, is a sort of deity of sea slugs, stewarding their evolution, watching over them, forever tweaking them for survival and aesthetics. It’s a loony sort of notion but played with a completely straight face, and it works. Birdsall’s creature is intrigued by the vents in the ocean floor: what if they hold life? Creatures such as itself, responsible for the evolution of highly specialized organisms of these molten crevasses? The creature investigates the only way it can: with slugs. Summarized, the story sounds ridiculous, but in practice it works. It is intriguing and well-written and raises many enjoyable questions.

In “Tocsin,” B. Morris Allen meditates upon ecology from the point of view of a derelict ocean structure surrounded by choked and polluted seas. The use of a structure as protagonist, particularly in a story about ruin, inevitably recalls Ray Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains,” to which, sadly, few stories can measure up. This one isn’t bad, though, describing the seas around its protagonist in prose both lush and brutal. It’s the most successful of the very short stories in this issue of Penumbra, although, again, the form precludes major involvement. It succeeds not so much because of what is in the story, but because of what it makes us think about.

[Editor’s note: Due to a possible conflict of interest I have agreed to review the following story.]

“Ms. Chalmers and the Silent Service” by Helen Jackson

Reviewed by Dave Truesdale

In Helen Jackson‘s alternate history story set not too long after WWII, a young British woman working as an office Temp is rounded up by a secret government agency of the Royal Navy known as the Squid Squad. Seems giant squids were bred to be larger and angrier and trained to attack anything made of metal during the war (U-boats in particular), and now one of them has escaped. We learn that the aunt of the kidnapped young woman was able to command squid through her voice during the war, and the Royal Navy’s Squid Squad believes our young woman can as well. Aboard a submarine a giant squid is located and begins tearing the sub to pieces. Just in time, and via an underwater microphone, our young female talks to the squid with phrases like “Bad squid,” “Squid, stop that,” and “Good squid.”

This extremely short story ends with the following sentences, after which, and with great restraint, I offer no comment:

“I’d learnt something, though. The family voice could intimidate giant beasts. I needed a career that could put it to good use. I start teacher training in September.”

[Matthew Nadelhaft concludes with the following remarks:]

In the aftermath of this ocean-themed issue of Penumbra I have to consider the power of the seas over the imagination. If these stories are any indication, the sea prompts us to description, to elegy and allegory. That the most successful stories in this issue are the longer ones also speaks to the epic nature of their subject.