“The Silhouette and the Smoke” by Richard Baldwin

Reviewed by Stevie McMichael

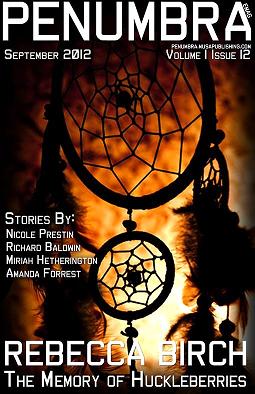

This issue features a Native American theme. The stories range from sad to bittersweet to unsettling, and not a bad one among the bunch. You might want to have some Kleenex on hand for this one.

“The Silhouette and the Smoke,” by Richard Baldwin, is the story of a pair of lovers in a tribe without verbal language who are taught to speak by a bear. They had married without the blessing of the woman’s father, Chief, who put a curse on them to drive the husband, Branch, away. The curse allowed the bear to teach them speech, and Chief stole their language, spreading it through the rest of the tribe. Believing the capacity to speak would die with the bear, Chief is unwilling to kill him, and instead imprisons him. Branch and his wife Quiet must both rescue Bear and kill Chief, an action that might kill their love as well. A sweet, sad story of innocence lost, that found me grieving even for Chief, whose first use of speech was to create the tribe’s first lie.

“Dream Catcher,” by Miriah Hetherington tells the tale of Asabi, a spirit that inhabits dream catchers, and is drawn to a woman who purchases one in an attempt to stave off nightmares. He feeds off the nightmares and grows strong, but pities his host, an artist who loses her creativity along with her bad dreams. Determined to use her to set himself free, he allows her to see him fighting one of her nightmares, and in gratitude she burns the dream catcher and releases him from his prison. It’s a short, bittersweet tale of relief and release, and one that left me smiling.

In “The Memory of Huckleberries” by Rebecca Birch, a dying woman speaks with the forest spirit who fathered her daughter. A pale, blue-eyed boy had washed up on the shore of her village, bringing a sickness that has already killed most of her tribe. The ghosts of the dead wander the village, unaware that they’ve passed on. Her dying wish is to see her daughter, who married into another tribe and bore a grandson she’s never seen, but she’s warned that if they come to her while she lives, the sickness will pass to them, too. She allows herself to die, but her spirit lingers long enough to see her daughter and grandson approach the shore. It’s a sad story of grief and love. This was the one that had me reaching for the Kleenex.

In “The Bone Train” by Amanda Forrest, Jacob, a charman, finds human remains mingled with the bones of buffalo he burns for char. Unsettled by this discovery, he wants to do something to honor the dead, so he deliberately over-burns the bones and allows the ash to float away. When the fire has burned itself out, he watches the souls of men and bison disappear into the dawn. A melancholy little story about a simple man who wants to do right by those long dead. I found it interesting to find a tale from the white man’s perspective, and Jacob made for a good protagonist. He’s the only character who seems to care about who and what feeds their fires, and I liked that he was willing to sacrifice some of his salary to honor the dead.

“She Who Waits for the Rain,” by Nicole Prestin, tells the story of Naomi, a meteorologist in charge of the satellites that have regulated the Earth’s weather for half a century, who sabotages it to unleash what she refers to as the Thunderbird. She’d dreamt of the Thunderbird for years before her sabotage, half believing it to be the spirit of the weather that wished to be released. She allows herself to be killed as the first storms of the freed Thunderbird take over the sky. It’s a brief but chilling look at a world that has turned weather into a weapon, only to have it break loose and take out its fury. Short though the story is, it left me a little unnerved, in a very good way.