“The Dragon of the Apocalypse” by Larry Hodges

Reviewed by Daniel Woods.

“The Dragon of the Apocalypse” by Larry Hodges

In the Oval Office, where battles are fought and won from leather chairs and hardwood desks, a razor-sharp word or two is the weapon of choice, and none are more deadly than those of the President’s golden rule: do unto others before they do unto you. With re-election coming up, and the Chinese Ambassador already making trouble, the President is playing hardball. Gotta be tough on people if you expect to win. But when an unidentified aircraft stuns the politicians by landing squarely on the US Capitol and flicking its tail, that golden rule may prove to be the President’s downfall – and the end of humanity’s reign altogether.

Larry Hodges’ piece is the first in an issue of SF political satire: a tongue-in-cheek story about the comic uselessness of politicians. The President and his contemporaries wear their official titles like ill-fitting costumes, and a circus-act lineup of bad toupées lets us know that these heads of state are not to be taken too seriously. Unfortunately, Hodges’ attempt at caricaturing the leaders of a nation often fails to amuse, due in part to awkward physical depictions (too-tight facial skin, etc.). The most successful humour seems to be accidental, in a hilarious bit of self-clarification from the author: “the president felt like a queen bee,” we are told, “though only in the most masculine sense” (an afterthought to appease any reader who might think this finicky president with his delicate high cheekbones is secretly a woman… or gay..!).

Hodges’ opening is a bit of gung-ho, overly patriotic nonsense, and by the time “Bruce the Hulk” strolls in, I’m bored stiff. The plot twist too comes as no great surprise, but the story’s one saving grace is the dragon, whose no-nonsense (extremely violent) approach to negotiation is grizzly and satisfying. While caricature is an excellent tool for political satire, Hodges’ President is just an awkwardly feminine man in a hideous blue and green suit. Indeed, by the time the dragon arrives and the world is in peril, the first thing on Mr. President’s mind is a distressing lack of candy (M&Ms are very important to him). If I’m honest, I didn’t quite know how to react to that.

“Mr. Kick-Ass Werewolf President” by Sarina Dorie

“I thought things would be different when they elected a werewolf for president,” my wife says.

If the title left you in any doubt, Sarina Dorie’s opening line makes no bones about it: the President is a werewolf, and the world has gone rather Gothic on us. “Mr. Kick-Ass Werewolf President” is a piece of flash fic about political disillusionment. When the seemingly impossible happens – werewolves and shapeshifters come out of the shadows, and one of them gets elected – it turns out that even a lycanthrope makes a lousy politician. A quick sketch of debates about healthcare for the undead, a mention of prejudice against werewolves, and the result is an inoffensive, wry interpretation of public scepticism.

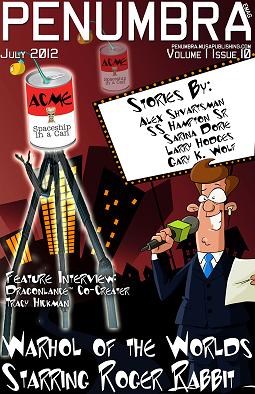

“The Warhol of the Worlds: A Radio Drama as performed by The Toontown Theatre On the Air” by Gary K. Wolf

When Martians land in Toontown California, Dan Blather is first on the scene, reporting live on PBS (the Public Bullshooting System). Gary K. Wolf’s story is a transcription of that broadcast, chronicling the horror that ensues when aliens land. A massacre of bunnies, a giant Marilyn Monroe, and the destructive power of a can of Campbell’s Meatballs are just the first of humanity’s woes.

Wolf’s piece is set in a cartoon universe, and allegorically pokes fun at society by poking fun at the characters we know and love. From Buggs Bunny to Marvin Martian, nobody is safe, and the plot quickly descends into the absurd. There is a charming quality to some of it – the terrible puns in the character names (“Percy Litigious” the lawyer, “General Chaos” the army commander) for example – but reading this piece gives you an idea of how Alice must have felt just after she’d fallen down the rabbit hole. Utterly bemused.

The ending is a brilliant, epiphanic moment, and I have to give Wolf credit for its construction – the sudden clarity hits you like a baseball bat to the face when the point of this whole ridiculous story is finally revealed; the words “oh no he di-n’t” sprang unbidden to my lips. Whether you’re delighted or infuriated by this piece, you’ll have a strong reaction to it, and that is a difficult thing to achieve for any author. Equally impressive is the fact that Wolf managed to link Marvin Martian, a giant Marilyn Monroe spaceship, and a tin of Campbell’s Meatballs together convincingly.

Nevertheless, Wolf’s argument is a stale, familiar rant about the gullibility of “the masses” and the evils of television. It’s anti-mass-media, anti-politics, anti-Corporate-America, and anti-anything-else-you-can-think-of-because-people-are-stupid-and-politicians-are-despots-and-the-press-are-trying-to-mind-control-us-all. It’s unimpressive, vaguely petulant stuff… but it’s damn effective when it hits, and for that, Wolf deserves a doff of my cap.

“Price of Allegiance” by Alex Shvartsman

Aboard the Union Central Station, humanity has finally joined its interstellar comrades, and taken a place in the galactic community. Unfortunately, that place is right at the bottom of the pecking order; humans are a new, rather primitive species. Alistair Tobin stands as Earth’s representative, and negotiates with the Cicadas for access to the Union Database: a repository of the collective knowledge of all the sentient, spacefaring races. Yet while a century or two is nothing to the Cicadas (greatest of all the Union species), humans are short-lived, and disinclined to wait for their acceptance. Impatience and the promise of new technology will bring Earth to the brink of starting a galactic war.

Alex Shvartsman’s piece is the most entertaining of the issue, and paints a familiar picture of humans as the upstart, disadvantaged “new blood” in town. Our place in the galaxy is predictably marginal, and the story is – for the most part – an amalgamation of recycled ideas. Insect-like super race that oversees a galactic coalition, humanity rife with greed, big glassy space stations full of bright lights and hazy descriptions. Very little here is new or exciting. The entertainment, therefore, comes from Alistair’s dogged idealism (his faith in the values of the Union), and the utterly believable way in which humanity’s leaders abandon all attempts at diplomacy, and opt for brute force instead.

“Price of Allegiance” is a straightforward criticism of the perceived corruption in Earth’s governments, and it ends with a nice twist (although the conclusion is a little too clean for my taste). Shvartsman’s politics are a bit black and white – Humans bad, aliens good – but that doesn’t stop his story from being a fun read with a likeable protagonist.

“A Luscious Kurdistan Strawberry” by SS Hampton, Sr.

Within the fortified walls of the Calat Alhambra, delegates, heads of state and royalty are gathering under rose petals and riot gasses. The first ever G20/G4 summit will soon take place, and humanity’s leaders will redirect its future; Pareevash waits in the sidelines, and basks in the decadence of it all. When three beautiful women meet secretly in a nearby courtyard, Pareevash sees an opportunity to manipulate the politics of the world, using nothing more than a single piece of fruit.

“A Luscious Kurdistan Strawberry” is a perplexing tale about decadence and vanity – about the inherent corruptibility of those in power. The idea is that politicians and leaders live in an imaginary world, an illusion of flowers and thick walls, and this makes them more susceptible to manipulation; what goes on in private stays private, after all. SS Hampton, Sr.’s point seems to be that the strongest, most powerful people among us are (if anything) weaker than anyone else. We watch as three world leaders fall to the power of the strawberry.

For all its lofty commentary, however, this story is not particularly engaging. Endless purple-tinted prose gives it a soporific effect (magic sparkly raindrops and heady, romantic smells, etc.). Naked beauties wandering around in petal-strewn courtyards, a princess beloved by all and nigh the most beautiful woman there ever was… it’s all suffocatingly vanilla. Add to this a few moments of good old-fasioned bad writing (a “flotilla” of fighter jets? The author also appears to be suffering from Capital Letters Syndrome), and the result is a story that overreaches itself. Political intrigue is reduced to three ridiculous women fawning over a handsome soldier, and the ultimate question – who is the fairest of them all (strawberry strawberry on the wall…)? – becomes quickly tedious. The strawberry represents “vanity, greed, desire, and lust”; the whipped cream it sits on may well represent something a little more, er, basic. In fairness, the Kurdistan Strawberry may be a new take on Eris’s fabled Golden Apple of Dischord, and that is noteworthy if so. But unfortunately, an awkward metaphor about a giant fruit is not enough to rescue this rather disappointing piece.

“Rekindled Dreams” by Jamie Lackey

Reviewed by Matthew Nadelhaft

The latest issue of Penumbra, organized around the theme of dreams, opens with Jamie Lackey’s aptly titled “Rekindled Dreams.” The story tells of An Lam, a slave in a tea house, dreaming of escape from her vicious master, Huang Fu. Though simple, the piece is well-written and satisfying, and brings to mind classic Hong Kong cinema. The mysterious stranger, the other slaves who need An Lam’s protection, even the description of An Lam’s duel with Huang Fu, could all be found in a Tsui Hark movie – and, indeed, are fairly predictable to anyone who’s seen a few such films. But familiarity, in this case, breeds comfort, not contempt.

“A Gentleman’s Needs,” by T. D. Edge, opens with a similar scenario: the lord of the house demanding the sexual services of his youngest maid. Her youth gives him pause – until he realizes it’s just a dream. But the dream is more than a dream, and his actions have consequences in the waking world. There is humour in the writing, but the tale is slight and comes to its conclusion too quickly and with little debate about the differences between our dreaming and waking lives.

Polenth Blake’s “The Road to the Beach” is about dreams chiefly by being as enigmatic and undecipherable as one. A woman walks endlessly along a road in a dream landscape, kept company by whispers. Life-events take place; she has a baby, yet no other characters enter her world. It’s as if this haunting and elusive story is about dreaming and makes sense only from the perspective of a reader inhabiting the same dream. It’s a memorable story, yet I half expect it to fade from my mind in a few hours, like one of my own lost dreams.

“A Dream of the City’s Future,” by Daniel Ausema, is another dreamlike story, but a self-conscious one, filled with references to some sort of meta-dream taking place within and around the surface narrative of a brother and sister scavenging around a floating village. As with dreams, there is no background, no exposition. Just narrative, symbolism, and obscure details. I don’t know what to make of the story – like a dream, it conveys more of an atmosphere and aftertaste than a story, and I get the feeling I would have to inhabit the head where it originated to understand it.

“Harpsong and Dreamsmoke,” by Lyn McConchie, has some of the mysterious and inexplicable nature of dreams, and mentions dreams a few times, but seems otherwise unrelated to the theme of this magazine. It’s a fantasy tale of a long journey from and through the unknown, filled with unexplained settings much like the two tales that preceded it. Unfortunately the story is repetitive and clumsily written. It hits a higher note with the ending, but not high enough to make up for the discomfort of its grammatical awkwardness and bombastic descriptions.

Patricia Russo’s “Circle Dance, with Pirouettes” is an excellent story, somewhat reminiscent of Timothy Pratt’s incredible “Rowboats, Sacks of Gold.” In prose and dialog both enchanting and humorous it describes a good-natured hunt as the narrator tracks down a mysterious stranger preparing for a trip to another world. The story is filled with the kind of mystery and whimsy I’m normally used to finding only in the pages of Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. But what it’s doing in this issue of Penumbra remains something of a mystery. It contains no mention of dreams. It possesses a dreamlike quality, of course, but so does almost all good fantastical fiction. Besides being the best story in the magazine, then, it has this other quality making it the natural final story – it moves us from the world of dreams into the world of fiction and demonstrates the two are mostly the same thing. The question, then, is what point is there to a magazine of fantastic fiction presenting an issue with the theme of dreams? All fiction is a dream, and the fiction we like is composed of the dreams we do, or would like to, share.