“The Girl and the House” by Mari Ness

Reviewed by Tara Grímravn

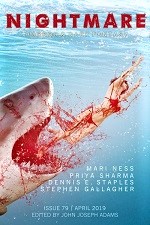

This month, issue 79 of Nightmare includes two original short horror stories. The first by Mari Ness is a modern feminist twist on gothic horror while the second by Dennis E. Staples talks of justice in the face of systemic corruption and prejudice.

“The Girl and the House” by Mari Ness

In Ness’ story, a young woman arrives at a haunted house inhabited by both the living and the dead. The particulars of the house, she makes quite clear, are not necessarily important and neither are the details of who she is. The house could be overlooking the sea as easily as could be adrift on a foggy moor, just as she could be either an impoverished relative or a governess. Ultimately, such details don’t matter. During her time there, she meets a variety of men and women and, though they tell her of the house’s curse, she refuses to allow their eccentricities and fears from coloring her explorations of the old building—a building that she knows has waited for her to come, to help it find release from its history and a new life through her.

It’s no secret that, by modern sensibilities, gothic horror is sometimes seen as being full of social conventions that have long since fallen out of favor. In “The Girl and the House,” Ness has chosen to put a spotlight on all of these things but her intent is not to take a stand or preach against antiquated ideals. Instead, she’s making a very different statement altogether. Simply put, “The Girl and the House” is a work of metafiction. The protagonist is the author and the house is the gothic horror genre itself. Just as the girl purposely ignores what everyone tells her of the house’s legacy as she explores its secrets, so does the author shun negative perceptions and opinions of the genre as she navigates its tropes and clichés. In doing so, both protagonist and author are able to bring something new, dark, and wonderful into the world.

“The One You Feed” by Dennis E. Staples

Ms. Watersong is an Ojibwe woman working at her tribe’s casino. In keeping with an old Indian saying, she believes she has two wolf pups living in her heart, one evil and one good. She feeds them on the anger and frustration she feels over the constant stream of injustices suffered by her people at the hands of society. Ms. Watersong wants nothing more than to set her wolves free into the world and she eventually finds a way to do just that.

At the heart of “The One You Feed” (no pun intended) lies a question about dealing with both systemic and blatant racism. The historical treatment of her people at the hands of white settlers aside, even in modern times, Watersong continues to witness multiple events of a rather horrific nature, such as the dangers brought by a new pipeline, Native women raped and killed by privileged men who go unpunished, and a corrupt justice system. She’s expected to simply accept it, just like her elders have, but she doesn’t want to. She wants to fight back and the wolves provide a way for her to do so, while at the same time giving the reader a very satisfying ending.

Nightmare

Nightmare