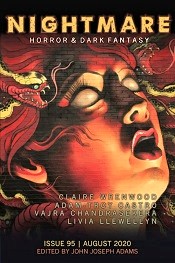

Nightmare Magazine #95, August 2020

Nightmare Magazine #95, August 2020

“Dead Girls Have No Names” by Claire Wrenwood

“The Hour In Between” by Adam-Troy Castro (reprint, not reviewed)

“Redder” by Vajra Chandrasekera

“Yours Is the Right to Begin” by Livia Llewelyn (reprint, not reviewed)

Reviewed by Tara Grímravn

Nightmare #95 brings to the table two original works that tell the stories of loss, of the dead and the dying. They are dark, yet despite their darkness, light in one form or another dwells at the end of these hauntingly grim and beautiful tales.

“Dead Girls Have No Names” by Claire Wrenwood

The unnamed narrator is comprised of body parts taken from several deceased young girls. Sewn together by Mother, they’ve been set the task of finding and killing the man who murdered and dismembered her teenage daughter. Night by night, they hunt down those who’ve killed other girls and consume them as they search for their target. But the pain of all those victims eventually becomes too much to bear even as they search for him on foot across the country, longing for nothing more than the warmth of life and a mother’s love.

Wrenwood’s story is a dark yet touching work with a focus on moving on from tragedy. Readers will note influences from classics such as Frankenstein as well as zombie tales in general. The pain the dead girls feel collectively (the story is written in the first-person plural) as they begin to realize that they were created to be little more than a nameless instrument for revenge, not a replacement for a child lost, along with the despair of the woman who created them is heartbreaking. This is genuinely a wonderful read and one I highly recommend.

“Redder” by Vajra Chandrasekera

It is 1986. Lured under false pretense, a man lies dying at the edge of a lake beneath a full moon on the night of Unduvap, 2530. He’s been horrifically tortured, his throat slit before his attackers fled the scene, their murderous rampage cut short by an approaching group of religious pilgrims. As life slips away from him, the apparition of his grandmother comes to mourn him and tell him a story from her childhood.

Intrigued by the mention of “Unduvap, 2530,” I had to do a bit of research before I could review Chandrasekera’s story. It appears that it’s inspired by the 1986 assassination of Daya Pathirana, a Sri Lankan student activist and revolutionary who was killed on the night of Unduvap Poya, which is a Buddhist full moon observance that celebrates the planting of the Bo tree sapling in Anuradhapura. The sapling is a popular pilgrimage site for many Buddhists.

Rich with cultural meaning and symbolism as it is, Chandrasekra’s tale is a bit of a hard slog to get through. The language style is somewhat abstract and very poetic, and there are a lot of cultural references that those from outside of Sri Lanka might not fully grasp. That does not at all lessen the impact it has, though. As an outsider, it was difficult for me to fully digest all that’s being implied, but I was able to get the gist of it. This is a tragic tale of a connection that spans generations, born of blood, grief, unrest, and pain that most everyone can understand.