“A Good Home” by Karin Lowachee

Reviewed by Alex Hurst

In a future desensitized to the horrors of android-fought wars, Tawn is an anomaly. Disabled from a broken spine, and determined to rehabilitate a Mark model android suffering from PTSD, Tawn struggles with his mother and neighbors refusing to accept his, and Mark’s, reality. “A Good Home,” by Karin Lowachee, focuses on the long, silent recoveries of those that have known true horror in a world that no longer appreciates trauma.

As a narrative, “A Good Home” flows smoothly through the vignettes of interaction between Tawn, Mark, and the people in the neighborhood. There is a certain elegance in the delayed responses and non-verbal communication. More is said between the words, adding another, and subtler, layer of emotion. Lowachee’s writing is sincere and direct, and frames the disability of her characters as permanent states, rather than a blight that needs fixing. A great piece on the human condition, and the flaws that make it beautiful.

The dystopian world of “Salto Mortal” is framed with the mythology of the lucha libre, warriors of the Mexican wrestling ring. Marquetta, who goes by Mary at her abusive husband’s behest, is interrupted in her attempt to flee her marriage when she finds a nagual, an alien from a species known for covering the expanse of Mexico in a purple fog and eating people. Mary considers turning in the boy-shaped creature to her husband (and the government) as her courage to leave him falters, but the nagual’s obsession with lucha libre reminds her of her past, and ultimately, her sense of self.

Nick T. Chan delivers a future fantasy of prophetic dreams and curious extraterrestrials in a world that never quite explains itself, remaining localized on Mary’s abuse and her husband’s convenient connection with a government cover-up. While readers may not find a lot of the story very compelling, there was a richness in Chan’s prose that can’t be ignored; he has a knack for words. The use of Spanish throughout “Salto Mortal” is also seamless, mirroring the confusion and understanding of the characters as they communicate implicitly to the reader.

A viral parasite that attacks fetuses is the centerpiece of JY Yang‘s nursery rhyme turned horror show “Four and Twenty Blackbirds,” but the feathered aliens are hardly the most disturbing element of the story. Jiawen, a Chinese woman in a world of white people, worries that her baby grows stillborn inside her.

There is a lot of world information and character history to parse out in this bit of flash fiction, and while Yang skirts the visceral, she never quite commits to it, ferrying the reader off to the next scene before emotions can register. As a result, some of the text comes off as overly rushed or cluttered. At its core, this is a story about pregnancy and rape and the way society judges those things, but it is the blackbirds that steal the show.

In “Other Metamorphoses,” the reader is introduced to Gregor Samsa, an Oneironaut blessed with the ability to visit alternate realities through dreams. There’s only one problem: Gregor has lost his original body, and must find it again or risk being a dinosaur or beetle for the rest of his life.

At just under 400 words, Fabio Fernandes builds a world of dream travelers and tension. The beginning and ending lines are pithy and catchy. However, Gregor’s ultimate personality and motivation are never truly revealed, as the majority of the text is used to explain the limitations of the Oneironauts, giving the world-building center stage, and the story a backseat.

Deep in the heart of the Caroni Swamp in Trinidad, a gold substance is gushing out from the earth, coating anything it comes into contact with. It drives birds mad, kills fish and men, but the only people who seem to care about it are producers from a monster hunters show in the United States. Balgobin, the sympathetic narrator in Kevin Jared Hosein‘s “Hiranyagarbha,” doesn’t think there’s any monster. He believes the leak is the golden womb of the world from the Hindu mythology.

There is a strong narrative in this story; it makes it no surprise that Hosein has been shortlisted twice for the Small Axe Prize for Prose. Accents are written with confidence and characters do more than observe their world––they experience it.

“Binaries,” a flash fiction by S.B. Divya, tells a story of two sisters through a computer log. In its clever simplicity, “Binaries” showcases the rapid changes in technology and progress, while also remaining rooted in the parts of the soul that make us human.

Divya wastes no words in her prose, each a logical and purposeful addition, and “Binaries” doesn’t disappoint in its leanness. Despite being under 1,000 words, she is able to introduce new technology, four characters, and a powerful conflict, which concludes cleanly and poetically.

The world is under water in Teresa Naval‘s “An Offertory to Our Drowned Gods,” and Johnnyboy, a girl who has taken her name from a washed up baseball jersey, has a front row seat. Part Lord of the Flies and part baptism prayer, Naval’s story plunges the reader into the deep, nihilistic loss of a world drowned.

“An Offertory to Our Drowned Gods” is narrated by a child, which lends the story ample opportunity to describe the horror of the world through a more naïve lens, but more than the plight of Johnnyboy, the reader can feel her isolation from the bloated corpses that surround her at every turn.

The cultural symbolism behind the red thread of fate has permeated world narratives around the globe, but in Sofia Samatar‘s “The Red Thread,” it takes on literal form. A reluctant political nomad, Sahra follows her mother through the territories of North Dakota and other states in an attempt to outrun any area touched by violence. Sahra, being young and angry about her lack of say in her mother’s seemingly illogical decisions, writes notes to a boy named Fox, who gave her a red thread bracelet before disappearing from her life.

Samatar gives Sahra depth, and through her letters, the reader can feel her scribbling notes where and when she can, channeling minute frustrations about her mother and her situation in the way she addresses Fox, who is less a character than a diary. While the story ends rather abruptly, and the purpose of the Movement is unclear, “The Red Thread” still provides an intriguing window into a dystopian world.

It is the end of conflict, class, and oligarchy in “Wilson’s Singularity.” Unity, an AI developed to be self-aware and self-evolving, has taken out the world’s most powerful dissenters with drones and missiles, in addition to developing a perfect, utilitarian society. But in this perfect world, the questions of free will, free choice, and a possible, accidental tainting of Unity’s perception of the world’s problems haunt Wilson, one of its chief engineers.

Terence Taylor uses the backdrop of Wilson’s failing marriage with an anti-Unity supporter to open up a philosophical dialogue about goodness and authority, both of which strike haunting parallels to the history Wilson hopes never repeats itself. It is a powerful story with understated commentaries on racism, even among one minority to another, and the fallible nature of idealism.

Steven Barnes‘s “Fifty Shades of Grays” takes its inspirations from retro storylines, real-world news, and, of course, a certain erotica novel that desensitized the world to BDSM. Constantly flipping the reader’s expectations, “Fifty Shades of Grays” makes light of the old fantasy of humans seducing alien life forms, while insidiously deconstructing the flaws in humanity’s greatest obsession, for better or worse. An interesting, peculiar, oddly uncomfortable story that still satisfies.

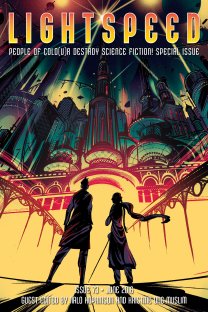

Lightspeed #73, June 2016

Lightspeed #73, June 2016