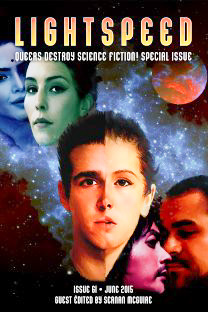

Lightspeed #61, Special Issue: Queers Destroy Science Fiction! June 2015

Guest edited by Seanan McGuire

Original Short Fiction:

Original Short Fiction:

Original Flash Fiction:

Reviewed by Cyd Athens

The subtitle here tells prospective readers everything they need to know about this month’s special issue. Regardless of one’s feelings, thoughts, or beliefs about either self-identified queers or the destruction of science fiction, this content not only visits the intersection of the two—both on Earth and offworld—but also hangs around for brunch, cocktails, and the after hours parties. Since this review will only cover the original stories, they are all that are listed in the table of contents above. However, there are also reprints, excerpts, author spotlights, nonfiction, and personal essays between these covers. One could easily mistake this issue for a rather large anthology.

The short fiction section begins with a story which includes potentially queer characters in a non-Western cultural setting. “勢孤取和 (Influence Isolated, Make Peace)” by John Chu concerns a squad of cyborgs ensconced on a military base by an organization, DAIS, which intends to destroy the cyborgs as part of a peace treaty. When one of the cyborgs, Jake, meets a man, Tyler, and begins to interact with him, it quickly becomes clear that little is as simple as it seems. The complex platonic relationship between Jake and Tyler, particularly as it relates to the cyborgs’ survival, is the meat and potatoes here. However, this is a story where their sexuality doesn’t matter. Unfortunately, the conflict between DAIS and the cyborgs is little more than a backdrop against which we see the situation between Jake and Tyler develop.

“Emergency Repair” by Kate Galey is the story of an unnamed narrator who is following instructions from a dead android of her own design to transplant the artificial being’s heart into that of his or her (narrator’s gender is also never disclosed) significant other. The narrator’s musings in between each instruction explains how the two humans came to be in a situation where the transplant became necessary. This is a story that alternately evokes both empathy and frustration with the narrator.

Rosalinda, a woman who has, like many in this fictional world, become a silent superhero as a result of a virus, is the protagonist of Bonnie Jo Stufflebeam’s “Trickier With Each Translation.” Rosa is temporally tortured by Archer, who believes himself to be the one true male love for her. He uses his super power to thrust Rosa in and out of time. This is a story that is full almost to the point of breaking. The characters, their histories, their abilities, and their relationships to one another are intentionally convoluted, which puts the reader right there with Rosa, disjointed in time. By the time the tale ends, one is ready to be in a single comfortable and solid timeframe.

“The Astrakhan, the Homburg, and the Red Red Coal” by Chaz Brenchley is a dialog driven narration. It concerns what happens when several companions on Mars are invited to enter into a drug-induced, shared, out-of-body experience where they function as a group mind and attempt to communicate with an alien. This is a group of men to whom this opportunity is delivered like a gift. The buildup is overlong, the journey itself takes considerably less time, and the ending kills any excitement a reader might have retained to that point.

Rustication is the government’s control method in “The Tip of the Tongue” by Felicia Davin. In a move evocative of Bradbury’s novel Fahrenheit 451 or the 2002 American dystopian science fiction film Equilibrium, the powers that be have decided that “an airborne plague of nanobots” which causes the populace to become illiterate is a good way to keep the masses under control. In addition, books, writing materials, art, and so forth are confiscated and destroyed. We learn of this world from Alice, a waitress, who used to love one book, Lily and the Dragon, and now can’t remember how to read it. As is customary when such draconian measures are instituted, people rebel. Alice gets in with the rebels, and the story, complete with unnecessary romantic interest—any romantic relationship in this story is unnecessary —takes its course. Not a lot of surprises here.

In case the title doesn’t give it away, “How to Remember to Forget to Remember the Old War” by Rose Lemberg is a postwar story. The unnamed narrator, who uses the pronoun “they,” suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. It is the nature of the war and the era which give this piece its science fictional bits. Otherwise, it is pretty standard coping with PTSD fare.

When Qiyan, the protagonist of Jessica Yang’s “Plant Children,” is at a loss for a senior thesis topic, she harkens back to her great aunt’s advice to have children. Qiyan’s interpretation is to create responsive plants which are sensitive in various ways—being particularly fond of light, touch, and so forth. Her roommate, An, lives with the flora invasion; friends and classmates visit for vegetables; and, her thesis is successful. Sadly, that’s about all there is to this story.

“Nothing is Pixels Here” by K.M. Szpara hits every note of this thematic issue, and should have been its opener. In this tale, Ash has grown bored with living as an avatar with his lover, Zane, in the pixilated world of the SimGrid. Ash wants to return to the flesh and blood world and eventually convinces Zane to go with him. To say more would spoil this excellent story. Recommended.

Amal El-Mohtar begins “Madeleine” with a Proust quote. Such phrases from her recent reading are key to helping Madeleine manage her episodes of memory disorientation which occur as a result of an experimental drug study—a clinical trial for an Alzheimer’s drug—in which she is participating. Within her memories, Madeleine meets Zeinab. While at first, Clarice, Madeleine’s therapist, encourages her to seek out the Zeinab in her memories, eventually Clarice feels that the situation is out of hand and that Madeleine requires more comprehensive therapy. This transition takes some interesting turns. The convoluted memories are used to good effect here.

On a post-disaster Earth, in a country which is now the Christian States of America, those who can afford to escape to the stars are going. In “Two By Two” by Tim Susman, Daniel and his husband, Vijay, are guaranteed seats on one of the shuttles. However, the shuttle is funded by Fundamentalists, and the pair will have to live the rest of their lives either in the closet, or persecuted. An interesting what if story about homophobia at the end of the world.

After a woman publishes an article about sexism in gaming, she is subjected to the usual Internet vitriolic trollery in “Die, Sophie, Die” by Susan Jane Bigelow. Her boyfriend leaves her and, although she blocks the perp who keeps sending her Twitter messages that she should kill herself, the woman continues to receive messages from that account. Eventually she takes matters into her own hands. The science fiction here is all about the technology.

“Melioration” by E. Saxey features Jay, a presence on a campus where one scientist, Morley, has developed a device for removing words from other peoples’ vocabularies. He demonstrates its function by removing an important word from Jay’s. Eventually, however, Morley goes too far and there are consequences to be paid. While the story itself is lackluster, the device is covet-worthy.

“Rubbing is Racing” by Charles Payseur takes full advantage of the flash form. It starts out fast, in media res, keeps going, and, before you know it, you’ve reached the end. Pilots speed to a planet’s surface, seemingly taking little care whether or not they are killed in their attempts to reach it. Behind them comes a world killer. This is one pilot’s tale. Recommended.

Alexandria Stephens, Claudine Griggs protagonist in “Helping Hand,” wastes thirty minutes resigning herself to certain death after a pea-sized meteoroid disables her mobility pack and leaves her spinning in space. By the end of the story, the title makes a lot more sense.

“The Lamb Chops” by Stephen Cox concerns a lover’s quarrel between two males, one human, the other, not so much. Disappointingly, it looks a whole lot like a contemporary spat between two humans.

The titular “Mama” in Eliza Gauger’s story is “vast, belt-born and zero-borne, seven feet long if she’s five.” She sounds like someone in whose good graces one would like to remain. This is a description of her provided by those who know her well—her kids.

In preparation for having her mind transmitted up to the Sing while her body stays behind, we see the “Bucket List Found in the Locker of Maddie Price, Age 14, Written Two Weeks Before the Great Uplifting of All Mankind.” Erica L. Satifka has used the list format well to tell a story that will resonate with anyone who has ever been a teenager and fallen in love.

The unnamed female narrator in “Deep/Dark Space” by Gabrielle Friesen is certain she has heard the baying of a dog… in space. This story is short and to the point.

“A Brief History of Whaling with Remarks Upon Ancient Practices” by Gabby Reed is not so much a story as it is a pep talk given by an unnamed and gender unidentified narrator to a group of new space whalers. The explanation of why the creatures are called whales, although they are quite different from their Earth-bound, cetacean counterparts, is one of the more interesting bits here.

Interrupted by just a couple of brief interactions with other characters, “Nothing Goes to Waste” by Shannon Peavey gives us the musings of a character who is being abducted in slow motion by aliens, one body part at a time. This reads more like a premise than it does a story.

What do you get when you mix contemporary American gay history with time travel? “In the Dawns Between Hours” by Sarah Pinsker. The day after she first kisses another woman, Tess realizes that society is not ready for such a thing in the year 1943 and begins working on a theory of time travel. She builds a machine and sets it for a date in 2015 expecting that things will be different then. For various reasons, however, her time travel trip keeps getting postponed. This is a dense story with a lot packed into less than a thousand words. Recommended.

“Increasing Police Visibility” by Bogi Takács is a story where extraterrestrials take the place of contemporary undocumented immigrants. We see the challenges faced by an officer charged with keeping the extraterrestrials out, as well as those faced by a person charged with providing the mathematical justification for continuing the practice of installing manned detector gates at border crossings for the express purposes of detecting any “illegally present extraterrestrial.” Gender-neutral pronoun use helps to keep the focus on the message of the story.

The last of the original stories in this issue is “Letter From an Artist to a Thousand Future Versions of Her Wife” by JY Yang. It concerns a woman whose wife, a scientist, has travelled into space on a journey which will take her light years away from Earth. The fly in this ointment is that the ansibles which were supposed to allow those left behind on Earth to continue communicating with their loved ones in space for at least part of the voyage are inoperable. In response, the woman decides to write a letter to her wife. However, based on her understanding of how these things work, the letter and her wife’s ship will be leap-frogging each other across time and space. Although the story purportedly uses the epistolary format, the letter goes unsigned, giving the tale the feel of one that has lapsed into a regular narrative.

Submissions for this special issue were open to “anyone who identifies as queer.” This had the refreshing result that not all of the stories feature queer characters or situations. Overall, as one might expect from any collection, there are some great stories here along with some that are merely good and a few that are lackluster. The range of stories, however, is broad enough that there is a little something for everyone—which is as it should be. Anyone who truly believes that queers—or anyone else for that matter—can actually destroy science fiction will be disappointed to learn that science fiction is still alive and well.

Cyd Athens indulges a speculative fiction addiction from 45ø 29 30.65 N, 122ø 35 30.91 W. Comments on Cyd’s reviews are welcome at www.cydathens.net.