“How Maartje and Uppinder Terraformed Mars (Marsmen Trad.)” by Lisa Nohealani Morton

“Houses” by Mark Pantoja

Reviewed by Richard Aphron

The new month of Lightspeed begins with a short story with a long title: Lisa Nohealani Morton’s “How Maartje and Uppinder Terraformed Mars (Marsmen Trad.)” The story interweaves two different styles of narrative that each present a different perspective on the same events. The first is an account of a family who are minor functionaries in the colonial government on Mars during a popular revolt, and are forced to escape to the nearby moon of Phobos to await rescue by Earth authorities. Alongside the personal story of escape is a mythologized recounting of the terraforming of Mars and the action Earth’s government takes against the rebelling “Marsmen.”

I liked “Maartje and Uppinder.” I’m a sucker for fables, and Mars is a wonderful site for a mythology — after all, the planet is named for the God of war and Phobos for his son, the God of fear. However, while I think Morton balances the elements well, the two narratives both undermine and reinforce each other — bear with me and I’ll pull the paradox apart a little. I thought the personal story gave relevance to the fable, giving it a human aspect with real emotion. However, I found the personal account incongruous with the mythology, and it left me wondering why two government bureaucrats would be at the center of a mythos shaped by the Marsmen rebelling against… people like them. It’s not a serious problem, I can think of a dozen potential reasons, but this is an example of how the personal story undermines the myth. “Maartje and Uppinder” creates a myth and dispels it in the same fell swoop.

The first few sentences of “Maartje and Uppinder” are good examples of the issue I outlined above:

Listen up, you Marsmen!

My mother’s suit was holed on the way to Phobos.

In space, you cannot hear a thing because your helmets are in the way.

The first line is direct address; striking, bold and attention-grabbing. Given the context, it might be a traditional start to the fable narrative, a call for people to gather and listen to a familiar tale.

The second line is in the passive voice. It describes a complex and dramatic situation without context — a common way to engage the reader by forcing him or her to try to deduce the context by reading more, and also pretty common in sf, where the readers are familiar with picturing an entire new world on the basis of a few lines. This would be the first line in the personal narrative.

However, putting them one after the other ruins both beginnings. The quick, direct promise of “Listen up, you Marsmen!” is immediately undermined by a difficult, confusing situation put in the passive voice.

The third line is just clumsy, and further undermines the two early attempts to grab the reader. Either the tense agreement has gone wrong; people wear more than one helmet at a time; or the first “you,” rather than addressing one reader, as is usually assumed, is used to address multiple readers at the same time. Personally, I thought you couldn’t hear in space because of the vacuum not propagating sound waves.

It’s worth getting through the confused beginning, because the story itself is simple and enjoyable. Its simplicity makes sense given the complexity of melding the two different narrative styles. Overall, I enjoyed “Maartje and Uppinder” and the inventive play of style it contains. It rewards a read.

I really enjoyed “Houses” by Mark Pantoja. The humans have gone, and they’ve left behind their faithful servants: a large autonomous infrastructure of intelligent buildings. How can these artificial intelligences find purpose when their raison d’être has abandoned them?

The story’s a little like Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains” in terms of the main idea of technology bereft of its creator, but Pantoja’s is quite a different beast. Where Bradbury’s is a beautiful story that’s more like poetry or a paean to the lost past, Pantoja’s is an active piece. Imagine if Bradbury’s house got up and said, “Right! I’m sick of repeating the date. Time to think about starting that novel I’ve been putting off.”

Pantoja creates a well-realized world and offers thoughtful insights into how our robot helpers would find meaning in lives without their creators. These offer reflections for the people who created these tools, but who are now absent. Objects often seem to come to mirror their owners and creators; imagine how much more that would be the case for intelligent machines.

Mostly I liked the story because it was a good, simple and nicely written story with engaging characters.

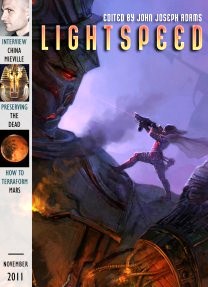

I enjoyed both stories, and also appreciated the variation of style and type of story. Adams and the hardworking people at Lightspeed have done a good job with this one, and with finding good, new authors, and I look forward to next month’s issue.