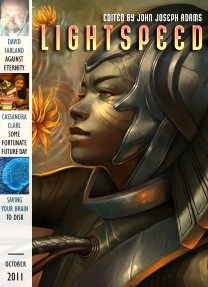

“Her Husband’s Hands” by Adam-Troy Castro

“Against Eternity” by David Farland

Reviewed by Richard Aphron

This month’s Lightspeed kicked off with a dark piece, “Her Husband’s Hands” by Adam-Troy Castro. Rebecca’s husband comes home from the war, but he has been gravely wounded. His hands were amputated — and they are all that remain of the man she loved. Luckily, SCIENCE comes to the rescue. The memories and personality of the husband she loved have been given in full to his severed hands and the hands themselves kept alive and well, and even well-manicured.

Rebecca struggles to unite the passion and love she felt for her husband with the expressive but, ultimately, grotesque hands that contain all that remains of him. Will their love survive, even though her husband has been wounded more than she realizes?

The story is well-written and filled with dark and delightful moments that would appeal to fans of horror, or even people who like zombie fiction. As science fiction it’s a bit of a close call. The story could, as the author acknowledges in an interview in the same magazine, have been told in a number of different codes (including as a story about zombies).

The scientific elements raise a lot of questions, but it was the unrealistic psychology that provided more of an issue. Specifically, I had no problem suspending my disbelief for the technology itself. I don’t know how a tiny sliver of metal can keep two hands alive and intelligent, but I’m absolutely willing to buy it. However, the idea that the government would take the time to restore a person’s memories and personality to a tiny scrap of severed tissue seems strange, and the story contains even more extreme examples than the husband’s hands: the strip of thigh living next door is an early example. If you’re going to perform medical and scientific miracles to give full life to a tiny piece of meat, then why not do something more useful, like returning the veterans as small robots or attaching them to animals? I’m sure the strip of thigh would have been pretty keen to have a cat’s body, and even the hands would probably appreciate metal legs. This couldn’t possibly cost more than whatever surgery you need to perform to keep two hands alive. My sense is that Castro wanted to write about severed hands, damn it, but I think he needed to do more to smooth out the speedbumps and make the premise more believable to an audience of critical science fiction readers. Nevertheless, if you’re able to buy the premise easily, then the story is interesting.

Castro’s story is an odd mixture of elements. This makes it quite a novel beast — perhaps one of the reasons Lightspeed selected it. Sometimes I thought the mix worked, and other times I thought it didn’t. The severed hands and Rebecca’s conflicted emotions toward them work pretty well. There’s a lot of surreal humor implicit in having a pair of hands come home from the war and try to pick up things with their wife. How does a person build a relationship with a pair of hands? The combination of serious emotional issue and outlandish severed hands worked, for the most part, well for me, making me uncomfortable but interested in this human element.

What worked less well was the same surreal humor applied to the issue of war veterans. The issue of war veterans returning home, wounded and changed, and how they can integrate back into society is extremely relevant to an America at war, with its own wounded veterans returning home. However, for me the flippant combination didn’t work, and only served to make the humorous qualities of the situation not funny, and the serious issues not engaging. This kind of dark humor is a fine balancing act! I was, however, pleased to see this theme appear. Science fiction has, historically, been a very useful way to talk about difficult subjects.

Overall, it’s an amusing story that’s worth a read, especially if you like your humor dark and absurd; you don’t think too hard about the physics of how severed hands would get leverage and balance; and you try not to think about the Thing from the Addams family.

“Against Eternity” by David Farland is a story about transformation. It’s a story about a long life, and what to do when eternity stretches out in front of you. It’s a story of expanding horizons, rebellion and individuality.

It’s also an unimaginative story, whose lack of originality is thinly concealed by couching the story in the uncommonly-used second person which, combined with the future tense, might possibly distract the reader from how thin the plot is.

Unfortunately, these stylistic elements only serve to highlight the story’s deficiencies. The second person and future tense give the story an impersonal feel since the protagonist obviously isn’t you and probably won’t be you. Instead, using “you” as the pronoun gives the story a more mythic feel, as if the protagonist could be a cypher for anyone. The story thus doesn’t seem to be about one person — and definitely not “you” — but rather a hypothetical possibility about a hypothetical person. Without any characterization or personal interaction, the reader is left with only the plot to provide interest.

The plot doesn’t provide interest. It follows a well-worn path through the fields of science fiction and takes very little in the way of divergence. If you want to read stories about people who become spaceships, you can read the many books in the “Brain & Brawn Ship series” by Anne Mccaffrey which she began in 1961. For most of the plot specifics, including the “twist” ending — and I use the word very loosely — you can read “Mr. Spaceship” written by Philip K. Dick in 1953. The latter seems ironic since Farland is, according to the bio supplied, a recipient of the “Philip K. Dick Memorial Special Award for Best Novel in the English Language” and should reasonably be expected to have boned up on his science fiction basics. At best, Farland is being highly derivative. At worst, he isn’t familiar enough with the genre he’s writing in.

On the topic of that Award, a little investigation (read: a Google search) revealed that Farland did not receive a “Special Award” at all, let alone one for “the Best Novel in the English Language,” but was nominated for the “Philip K. Dick Award” which doesn’t presume to judge which English language novel is best, but rather selects from “distinguished science fiction books published for the first time in the United States as a paperback original.” Farland won a “Special Citation” in the year he was nominated. At some point the citation seems to have transformed into a “Special Award” (by implication more special than the Award itself!), and “science fiction books published for the first time in the United States as a paperback original” turned into “the Best Novel in the English Language.” I don’t know where all this misinformation has come from. Some seems to originate from Farland’s own website where he has also, amusingly, misspelled the name “Philip” in his “Award.”

Farland is a published and well-established author who has real awards, so there’s no need to engage in this sort of stretching of the truth. When the misinformation is combined with a number of small errors — “Where have all the birds have gone?”, “When your friends and family are have all passed,” and “Ethiopa” — and both are combined with the derivative plot and alienating writing style, what we get is an example of poor writing and poor editing, made all the more extreme when it is coming from a decent science fiction magazine and a writer who has, he claims, “mastered science fiction.”

This month’s Lightspeed didn’t impress me as much as previous issues. “Her Husband’s Hands” had some points of interest, while “Against Eternity,” for me, had none.

REVIEW UPDATE 7/9/2012: David Farland has updated his website to correct some of the larger errors pointed out in this review. He still has a “Special Award” instead of a “Citation,” but he now spells “Philip” correctly and no longer claims to have won his citation for writing the “Best Novel in the English Language.”