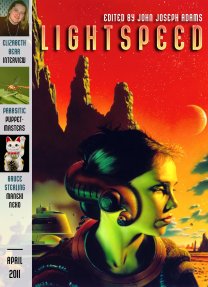

Lightspeed #11, April 2011

Lightspeed #11, April 2011

“All That Touches the Air” by An Owomoyela

“Maneki Neko” by Bruce Sterling

“Mama, We are Zhenya, Your Son” by Tom Crosshill

“Velvet Fields” by Anne McCaffrey

Reviewed by Indrapramit Das

As is the norm for Lightspeed, this issue features two original short stories, and two reprints, this time from Bruce Sterling and Anne McCaffrey.

An Owomoyela’s “All That Touches the Air” is an effective piece about a colonist on the planet Predonia, which humans share with the parasitic Vosth. The Vosth live in the ocean next to the human habitat, and have the ability to take over colonists and turn them into “flesh-suits” for themselves, should the colonists leave the habitat without the protection of environmental-suits. The narrator, curiously genderless for a character this well fleshed-out, is terrified of “infestation” by the Vosth, and practically lives in an e-suit (something colonists don’t do inside the habitat).

The story deals with the narrator’s struggle with her fears, as well as the Darwinian cold war between the Vosth and humans as the balance of power begins to tilt, threatening to make humans the dominant species on the planet and negate the Vosth’s original declaration that “All that touches the air is ours.” The narrator becomes a key figure in this struggle, if an unwilling one, making it all the more intriguing to see this subtle conflict unfold through her eyes. It becomes a fascinating look at inter-species diplomacy as conducted by a literally xenophobic neurotic and the zombie emissary of an alien hive-mind. Owomoyela crafts a convincing underpinning of alien logic behind the Vosth’s motives, making their (its?) apparent malevolence a veneer for something more interesting. Definitely worth reading, with a satisfying resolution and some fine writing.

Tom Crosshill’s “Mama, We are Zhenya, Your Son” deals with the Ender’s Game-like premise of a mythic child figure orchestrated by adults into tapping questionable power. Zhenya and his dog Sulyik are inserted into a virtual world interface by the sinister Dr. Olga, with the intention of using his malleable child-brain to access other quantum realities for energy and other nebulously defined goals. Zhenya detects that something is off about Dr. Olga’s approach and insistence, but keeps at it because of the promise of rubles to save his mother from penury.

My main problem with this story was the voice; five-year-old Zhenya is our narrator, and this obviously becomes somewhat of an obstacle in expressing what’s going on, what with the child becoming a semi-omniscient quantum god and trying to prevent a physics-based apocalypse. Crosshill makes another problematic restriction for himself by addressing it all to Zhenya’s mother. It all became too cloying and precocious for me, with the boy saying things like “qantumikal” and “soft wear glitch” and“Giness book of records” but somehow also able to muster the poeticism to ask his mother: “Do you feel my fingers on your back? See the curtains move?” The tonal maturity in these sentences is immediately evident, but entirely inconsistent, as Zhenya quickly lapses back into simplistic child-language after every phrase that doesn’t sound like a five-year-old could articulate it. If these flickers of maturity are brought on by his experiences in the story, there is no consistent evidence of it.

Similarly, the focus on the boy’s enduring and single-minded love for his mother and his dog, even in the face of the cosmic chaos unfolding around him, might have been touching in a third-person narrative, but comes off as too much and verging on manipulative in first-person. We don’t, after all, really see or hear the mother, or any other character (the dog and Olga appear, but in very distant, vague ways because of the narrator’s language), for that matter, making the story’s sentimentality unearned, and its human antagonist (Dr. Olga) a cartoon. It’s possible that some readers might appreciate the voice experiment here, but it didn’t do it for me, which is a pity, because I found the idea of a child trying to stave off a quantum breakdown of multiple realities all by his lonesome self a compelling one.

Lightspeed’s presentation continues to be top-notch, with a visually appealing and easily readable site, and satisfying extras/cover art to go with the stories. The high-calibre authors they manage to pull for reprints also ups the value. It shouldn’t be too long before it’s declared a SFWA qualified market like the also relatively new Bull Spec.