“The Code for Everything” by McKinley Valentine

“Man vs. Bomb” by M. Shaw

“Close Enough to Divine” by Donyae Coles

“Arenous” by Hal Y. Zhang

Reviewed by Seraph

“The Code for Everything” by McKinley Valentine

Talking cats, mystical realms, and disastrous parties weave a tale that would oftentimes seem unusual or outlandish. This tale of a young girl named Izzy is rather more relatable than the fae trappings would suggest, however, and within the indistinct modern setting very little of the world seems unfamiliar. All the many rules of social interaction are every bit as confusing, the people are just as judgmental and crappy as in real life, and Lord help you if you just aren’t wired like everyone else and none of it makes any sense. After a short meeting with a couple of very articulate felines, Izzy is whisked away to the Fae realms, and bestowed with a huge list of more than two hundred rules that must be followed at all times, to the very letter. I imagine most people at this point would be horrified, but for anyone to whom the first half of this story seems entirely too relatable, her relief at finding herself in such a place is no surprise twist of an ending.

“Man vs. Bomb” by M. Shaw

At any given time, the draw of a fantasy world is appealing for the simple fact that with a stroke of the pen, anything you dream of can become a reality. As with all such daydreams, there is a gamut run between the vicarious and the vicious. Stories like this one find their home where the two vices meet. In this case, it is humans and deer, with a side helping of zombie. These humans from an indeterminate future, no longer masters of the world and now captive to the obviously righteous and morally superior deer, are set loose on an obstacle-ridden racetrack to be pursued by the “bomb” which wants to eat them. All the while, the deer watch from the stands and bet on how long until the human is brutally killed (consequently being turned into the next bomb, in true zombie fashion) as if on a horse at the tracks. In amongst all the overwrought moralizing and tired false equivocations, the threads remain the same: the oppressed have overthrown their oppressors, and now find entertainment in killing their captives for sport. It is an increasingly common, if not remotely original trope, nor is it half as clever as it wants to be.

“Close Enough to Divine” by Donyae Coles

I am usually a huge fan of mythology, and nearly any fiction that draws upon it. This story just didn’t appeal to me in the same way, and I honestly couldn’t tell you why. The story follows Mona, an ancient creature of myth called forth by a worshipper at a modern day basement party. She is highly reminiscent of a harpy in how she is described, but also presented with elements that feel distinctly angelic and vampiric. The young man who has summoned her offers himself to her as a sacrifice, and she wantonly accepts. She is majestic, if terrible in nature. The tempo is well done for the subject matter, and reflects the character it describes: pacing, patient, and hungry all at once. It is fully descriptive, and I would even use the word immersive without feeling hyperbolic. It may be a bit too short, but again along the lines of the tempo reflecting the character, the story ends every bit as abruptly as the moment when she reveals her full glory and tears apart her sacrifice to devour it. It’s definitely worth a read, and even gets a recommendation. I just didn’t enjoy it the way I was expecting/ hoping to, and wish I could figure out why.

“Arenous” by Hal Y. Zhang

One of the most difficult types of stories to tell are those that take on the dual daunting tasks of trying to put words to the act of having life, and simultaneously explaining why the character desires not to. Either topic is ponderous enough on its own, but the author handles it well. Ponderous topics need a slow burn, plenty of time to digest the who, what, where, and why of it all. In this case, it’s Sarah, and she’s turning to sand one piece at a time. From her modest apartment, to her unsympathetic, uninterested, and altogether unhelpful doctor, to her modern office job, no one seems to notice or care how she is quite literally falling apart. It’s a somewhat subtle way of portraying helplessness in the face of indifference and isolation, something that feels all to real in the pandemic age. She evolves beyond it all, however, and reaches a different level of existence. It’s all very zen despite the subtle sadness that infuses almost every word. The writing is good, and the pacing is as well, but I think overall the story just kind of bends under the weight it is trying to carry. The topics within would be difficult enough to handle with ten times the words used here, which is no fault of the author, but does leave it feeling somehow a little more shallow, or at least far shorter than it deserves.

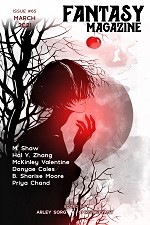

Fantasy

Fantasy