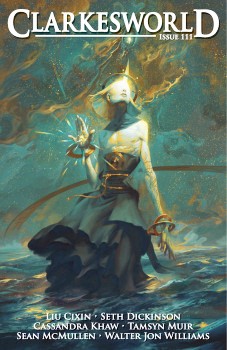

Clarkesworld #111, December 2015

Clarkesworld #111, December 2015

“Yuanyuan’s Bubbles” by Liu Cixin

Reviewed by Jason McGregor

The one hundred and eleventh number of Clarkesworld presents us with four stories, half of them (and by far the longer half) very good, making for a good issue.

“Yuanyuan’s Bubbles” by Liu Cixin

In the desert of northwest China, Yuanyuan is born. She is a listless baby until she discovers a love of bubbles. Yuanyuan’s mother is at work trying to make the desert fertile when she is killed in a plane crash. Her father, the mayor, carries on the mother’s dream. But Yuanyuan still loves bubbles. Eventually she learns to make Guinness-record-size bubbles by learning about surface tension and special methods of creation and using a special recipe. And then she starts to make really big bubbles. Matters reach a climax when her father realizes that Yuanyuan’s silly obsession may not be so silly after all.

This is a reprint from a 2004 Chinese magazine but is reviewed here in Tangent because it is a new translation. As such, I’m not sure if the initially annoying sing-song-y fairy tale tone is present in the original or is the fault of the translator but it diminishes, either intrinsically or through acclimation. And I can’t help but feel like I’m reading Chinese Communist Party propaganda as the story blithely assumes the South China Sea is China’s to do with as it will, along with similar bits of subtext. Those things aside, this is a well-structured and balanced story which, while still having a figurative and literary level to make humanity’s folks happy, deploys Big Ideas with an almost Golden Age casualness which reminds me of when America and its science fiction was similarly bold and confident and proud, recognizing the connection between dreaming and doing. I’ve avoided this author’s recent famous novel but this story raises the possibility that that was a mistake.

“Union” by Tamsyn Muir

This story is difficult to summarize because it’s difficult to understand. The author bio says the author is a New Zealander living in the UK, and the story is written in a dialect so marked that word choices almost seem to have been determined by the opportunity to vary from the Queen’s English. It makes it difficult to parse what is supposed to be science fictional versus what is simply regional or colloquial.

Examples from the first couple of pages:

The Franckton crofters stand and watch from behind the barrier. They’ve knocked off midday work to come. You can practically see the pong of hot mulch and melting boot elastomeric coming off them. There’s even a man there from the New Awhitu Listener to take pictures.…

“If the Listener links any of those photos,” Simeon’s telling the photographer, “you’re dog tucker, mate.” Simeon’s got the gist of it already…. [I’m glad someone does.]

“It’s a disgrace,” he kept on saying. “It’s a nothing. We’re getting gypped. We’re the highest-revenue croft and they’re shutting us up, they’re paying us off, the next time we don’t say how high when they say jump we’ll get our subsidy slashed and you bastards are falling over yourselves to lick their arse . . . ”

He got told off by the Mayor for whinging….

When the wives finally landed and they got their first eyeful, they knew there wasn’t going to be a picnic or a pōhiri….

The first thing the crofters hate is the names. Their wives have been given croft names, and that’s insult to injury, somehow. It’s ingratiating.

Ingratiating? Now there’s a perfectly Anglospherical word but it seems to be completely misused, with “infuriating” being intended.

Anyway, in some future in which a Ministry runs everything, biological sciences seem dominant and some kind of plant/women hybrids are supposed to help small farmers (if they aren’t a bit of sabotage from the government as one of the more significant characters maintains). The populace of the village is distraught when the plant-women seem to be causing contamination in the homes, then perhaps damaging the crops, before finally causing the death of a goat due to some type of plant-like fungus/spore. So the main instigator resolves to kill all the plant-women and the villagers acquiesce. Naturally, things are not taken care of so easily and horror ensues. I’m sure, as Hawthorne might say, it all could be “symbolical of something.”

On a literal level, however, the background is not explained and a future in which small farmers exist alongside futuristic bioengineering, when small farmers are already being eliminated by giant industrial farming, could use a rationale. The story falls between two stools, lacking the detail and logic to work literally while having too much to allow turning off those centers of the brain and working as a pure dream/nightmare.

“Morrigan in Shadow” by Seth Dickinson

This is a complicated story, and not just because it is three-stories-in-one and a sequel to at least one other. (The previous story is “Morrigan in the Sunglare,” from the March 2014 Clarkesworld, for which there may be some implicit spoilers in this review.) The overarching story is of a war between two human factions, the essentially pacifist Federation and the extra-solar colonists of the Alliance (Asimovian “Spacers,” in a sense), when the latter run into the sentience-hunting alien Nemesis (Berserkers/Inhibitors/etc.). The Alliance tries to recruit the powerful Federation to help them; the Federation refuses; the Alliance attacks the Federation to seize their resources for the larger fight. As this particular story opens, the Federation government has surrendered to the Alliance but the military mutinies to continue fighting. The three stories, or components, are called “nagari,” “simms,” and “capella,” and consist of about twenty-nine interwoven pieces. As the second of nine “simms” segments indicates, “nagari” is the beginning and deals with Laporte (callsign, “Morrigan”) joining a sort of black ops group within the Federation; “simms” is about Laporte’s and Simms’ relationship and is the transition to “capella,” which deals with a fight around a black hole between Morrigan, an Alliance flagship, and a Nemesis worldwrecker.

Such is a (wholly inadequate) sketch of the structure and plot but this is a “theme” story and provides much food for thought and may have readers going through several phases and feelings, along with reorientations of perspective, especially with the twists at the end. One of the two main thematic elements regards Laporte and Simms and their love for each other. Some of the foreground literalness is sacrificed to the symbolism of Simms/Laporte as a kind of (not exactly) Apollonian/Dionysian pair but the foreground literalism always has some validity. This feeds into the second thematic cluster of life/death/growth/cancer/peace/war/idealists/monsters.

How well this story works for the reader probably depends on their tolerance for non-linear narrative (mine is often quite low), for a sort of Space: Above and Beyond-style super-grit tone (mine is often quite high), and basically how much the military space opera imagery and themes appeal to them (quite a lot to me), and—beyond the narrative strategy—how well the narrative style works. Given the section titles, additional introductory sentences sometimes seem clunky but perhaps they are necessary with the somewhat confusing structure. And there is a sort of distancing produced by the present tense but firmly third-person (however omniscient) approach. (That is, much third-person omniscient narration takes on the flavor of the characters or focuses tightly on them or otherwise makes them seem very close while this story keeps a character-independent style of narration and, despite Morrigan being the absolute protagonist, tends to traverse wide fields.) But Dickinson excels at figurative language, choosing unexpected but apt and unstrained metaphors and similes. Of a military abandoned by its politicians:

This is the lean time between the surrender and the mutiny, when the Federation’s surviving fleet lurks in the cold on the edge of the solar system, a faithful dog cast out and gone feral.

Or of Laporte’s painful experiences:

Laporte’s a monster now. Her past is useful to her only in the way that gunpowder is useful to a bullet.

In sum: a complex story that must be told with complexity but is still perhaps more complex than it needs to be, especially as much of the imagery and plotting is not, fundamentally, all that novel. It won’t appeal to everyone but, still, I recommend it. “Morrigan in the Sunglare” is in the current The Year’s Best Military SF and Space Opera and I will be surprised if “Morrigan in Shadow” isn’t in next year’s.

“When We Die on Mars” by Cassandra Khaw

A woman ponders healing old (unspecified) wounds with her family and observes others who do or do not handle things in their own lives as all of them prepare to go to Mars. The why and how of that is never made explicit either, but it seems obvious that Earth is so ruined that we have no choice but to try to make another planet habitable. (Though how we would be able to terraform Mars and be unable to re-terraform Terra is not obvious.)

Underplotted, overwritten, faux SF which is not at all actually interested in literal Mars.

Jason McGregor’s space on the internet can be found here.