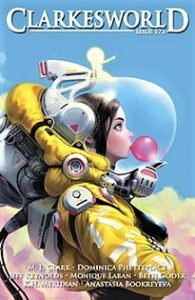

Clarkesworld #173, February 2021

Clarkesworld #173, February 2021

“The Failed Dianas” by Monique Laban

“Terra Rasa” by Anastasia Bookreyeva, translated by Ray Nayler

“Obelisker Adrift in the Desert” by K. H. Meridian

“Mercy and the Mollusc” by M. L. Clark

“ “Remember The Washington,” They Said as They Fed the Ugoxli” by Jeff Reynolds

“We’ll Always Have Two Versions of Pteros” by Dominica Phetteplace

“History in Pieces” by Beth Goder

Reviewed by Mike Bickerdike

Clarkesworld features 7 stories for February 2021, including 1 novella, 1 novelette, and 5 short stories. This issue features several science fiction stories set on new colony worlds.

“The Failed Dianas” by Monique Laban tells the tale of a meeting of 5 clones of an Asian woman (the ‘original’ Diana) in her restaurant on Earth. Each has been created by the parents of the original Diana, as she and each subsequent clone did not attain the role and success they were hoping for. The protagonist, the fifth Diana, discusses with them their lives, and considers her own future and the merits of following her own path. It’s quite a well-told tale and engages the reader at the start but it lacks an especially original spark to bring it to life and ultimately falls somewhat short in both plot and conclusion.

In “Terra Rasa” written by Anastasia Bookreyeva and translated by Ray Nayler, we are introduced to a dystopian future in which the world is on fire. Fire tornados have razed the cities of Russia and daily temperatures have soared. The world is collapsing into disarray. A young woman who volunteered as a rescuer, and therefore has a first class pass to travel, is taking the last train north to Murmansk to catch an ark ship to the arctic. The tale is pretty grim and Bookreyeva suggests there’s little hope humanity would cope well with such extreme conditions. The tale is largely unremitting in its grim outlook and, other than some striking imagery, does not offer all that much for the reader—that is, until the conclusion, which conveys some tension before leading to a clean conclusion.

“Obelisker Adrift in the Desert” by K. H. Meridian is a highly entertaining and engaging novelette. Sometime in the far future, after human civilization has fallen, a few of the great computers still exist, mainly underground, perhaps one in orbit. One such computer exists as part of a great alloy obelisk in the desert. Around it lies the sandy remains of the human city that once flanked it, settled by those who misguidedly thought the computer would protect them. But the computers’ aim was to destroy each other—how could it be anything else if they were made by humans? To the obelisk computer comes a ‘panzergrenadier’; a cybernetically enhanced female with powerful weaponry and a wistful need for company. This story, told with humanity and panache, has original ideas that are developed in a tense plot that satisfactorily resolves. A superior science fiction story that should have wide appeal.

“Mercy and the Mollusc” by M. L. Clark is a science fiction novella, set on the colony world of Maia. The original atmosphere of volatile fumes has been terraformed, with the exception of pockets of the old-world in which native flora and fauna still exist. The protagonist, an ex-soldier, travels the land collecting specimens to preserve what alien life he can, aided by his long-time companion, a giant sentient mollusc. Over the course of the story, he learns more about what drives his mollusc companion, and how the deep-seated guilt he harbours from his soldiering days has limited their connection. The idea of riding around on sentient molluscs and the descriptions of the planet offer some originality, and the story manages to maintain interest over the course of quite a long tale. Engagement in the story is hampered by its delivery, however; patches of purple prose slow the narrative, and the dialogue (both internal and spoken) is unconvincing in places. We learn the protagonist’s name early in the story but from then on, he is still referred to only as ‘the man’, which holds him at arm’s length from the reader. Indeed, the characterisation of ‘the man’ is rather thin. Overall, while the story has its positives, it doesn’t quite capitalise on an interesting premise.

“ “Remember The Washington,” They Said as They Fed the Ugoxli” by Jeff Reynolds tells of a veteran of an interstellar war with unnamed aliens, who is deeply troubled by the work he had to do recovering frozen bodies from space after the destruction of a spaceship, The Washington. Set on an alien world, this story bears some structural similarities with the previous novella, in that the protagonist is never named (a mistake in my view), and it’s also set on a colony world which provides little comfort. The feeding of the Ugoxli refers to the feeding of a baby to an alien predator—an ugly image which presages more ugliness to come, as the unnamed veteran delivers further retribution to others in the community. The moral compass of this story is confused and while the protagonist’s actions are, in theory, partially excused as we learn more of what is really going on, he is unlikeable, and the story gives the reader neither a character nor an outcome to root for.

“We’ll Always Have Two Versions of Pteros” by Dominica Phetteplace is a very short story, in which a man is shifted to a timeline that is not his, by alien intervention, and then later shifted back to his own timeline. In the different timelines he experiences different outcomes in his love life. There’s not an awful lot more to say about it without simply retelling the little tale. It read somewhat like a humorous piece in its style, but there wasn’t much here that amused, and as a serious piece it wasn’t especially satisfying. A short diversion, it won’t take you long to read.

“History in Pieces” by Beth Goder is another very short piece, but nicely done. This month Clarkesworld features a number of stories of the colonisation of alien worlds, and this is another example. The story is told from the perspective of indigenous alien ‘archivists’ who secretly recorded the activities of arriving humans to their planet. Brief snippets of this human history are retold here in a fragmentary way, jumping back and forth in time, but the overall impression is clear and quite effective.