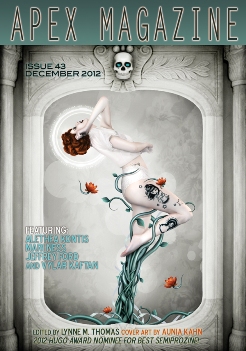

Apex Magazine #43, December 2012

Reviewed by Matthew Nadelhaft

Apex concludes 2012 with a question-mark wrapped in an enigma, presenting us with two obscure and mysterious stories – three if you count the long and extraordinary reprint by Jeffrey Ford. After I finished reading Ford’s lengthy parable I was quite disappointed to discover it was a reprint, in fact – I’d been very much looking forward to reviewing it, for, as usual with Ford, I had enjoyed it immensely. The other stories were a bit more problematic for me.

Alethea Kontis’s “Blood From Stone” is a dark piece of fantasy concerning the lord Polecat, his maid Henriette, who loves him, and his sorcerer Prelati. Polecat, for whatever reason, is desperate for a divine visitation and, when he despairs of receiving one, Prelati convinces him to set his sights quite a bit lower. Henriette insinuates herself into their confidences and soon proves an invaluable complement to their dark schemes and rituals. Eventually, thanks to Henriette, they achieve success – of a sort. And one might expect, the price paid by the characters when their bloody work reaches fruition is high. The story is well-written and suspenseful, but hovers awkwardly between the real world and fantasy, with a reference to Jeanne D’Arc and a personification of death who speaks in colloquial English, at odds with the rest of the prose and dialog. Its main problem is a lack of characterization which renders the actions of Polecat, Henriette, and Prelati hard to decipher. A powerful ending is undercut by the lack of any obvious motivation to explain how the characters ended up at that point. It’s as though they move along a predetermined course and we follow them – enjoying ourselves as long as we don’t demand too sensible an answer to the question “why?”

“Labyrinth,” by Mari Ness, is a similar reading experience. With excellent and evocative prose it tells an ambiguous tale of “dancers” who wait at the centre of a labyrinth to kill in ritual combat those forced by the masked priests into the treacherous maze. The story follows the leader of the dancers as she watches her children, most of them also dancers, grow until one of her daughters takes part in her first dance, with her mother as a partner. It’s like a humanization of the minotaur myth – both in that the minotaur is replaced by human characters with lives and families and that the entire institution of the labyrinth is given a social utility of some sort. Unfortunately, I found myself more intrigued by that social utility, and by the culture which might employ a labyrinth with its deadly dancers, than I was by the actual story and its characters. And about the setting, the positions of the priests in society, the religion they represent, the reasons why one might find oneself condemned to the labyrinth and what function justice enacted in this manner could possibly play, nothing is said. The setting is the real maze at the heart of this story, waiting to be unravelled by the reader. Unfortunately, the plot leaves few clues or threads to follow.