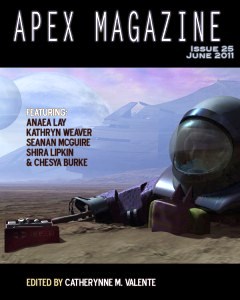

Apex Magazine #25, June 2011

Apex Magazine #25, June 2011

“The Doves of Hartleigh Garden” by Kathryn Weaver

“Your Cities” by Anaea Lay

Reviewed by Dave Truesdale

“The Doves of Hartleigh Garden” by Kathryn Weaver is her first published short story. There’s no fantastical element present as the story relies on a dark, depressing, decaying atmosphere for its effect. We have a crumbling manse with a bit of land (Hartleigh Garden), and an evil, over-protective widow who marries a widowed (and not so rich) lawyer with a young son who is counterpart to the widow’s young daughter.

The daughter and son grow quite fond of each other, as they share their love of nature and drawing. Time passes and the son is off to war (WW I) and is severely wounded. Upon his return to Hartleigh Garden the mother perpetrates an unspeakable evil to insure her daughter will inherit the crumbling, sinking, muddy, rat-infested mansion. After the daughter becomes aware of this dastardly deed, she is momentarily conflicted as her filial affection for her stepbrother competes with her desire to inherit Hartleigh Garden and its lovely doves (who always liked the stepbrother best). She remains silent to her mother’s deed, and at story’s close we see her in much the same state as her mother at the age of thirteen, sitting in the little garden with the doves hovering around her, with no hope, no future, and the crumbling mansion in the background slowly sinking into the earth–a perfect metaphor for the girl’s life as it too sinks into oblivion.

If you are the sort who likes the dark, depressing, and utterly bleak, with a bit of murder to top off your day (with doves), then this is definitely for you. Me? Not so much.

Anaea Lay‘s “Your Cities” uses the device of cities coming literally alive and destroying their buildings, bridges, and basic infrastructure—seen from the author’s eyes as bad, a blight, and an evil. San Francisco and San Diego march on, and destroy soulless Los Angeles, “a stinking mass of ghettoed neighborhoods and highway united by a central strip devoted to tourists and hookers. You said there wasn’t enough human soul there to keep the people from turning to plastic. You called it an abomination,” while Milwaukee and Chicago perform the same service on Green Bay.

The unnamed narrator (male or female it matters not)—who is at first in shock at these developments—tells the story as if talking to a departed lover (male or female it matters not), who is in favor of such happenings and has traveled around the country to witness each city’s “coming alive.” The story is quite short, and near the end the narrator has changed his (the generic pronoun in English) mind, to wit: “I work on a farm now. They’ve sprung up where the suburbs used to be. The cities are riddled with markets selling fresh produce.”

Well, what to say? Cities bad, the rural farm life good. No in-between. Back to Nature all the way. This is the primary message here, and it’s a very old one. Written about in fiction, newspapers, and magazine articles, discussed in classrooms of higher education (urban sociology courses) for nigh on to one hundred years or more (see, for example, Stephen Vincent Benet’s 1935 poem “The Revolt of the Machines” [a.k.a. “Nightmare No. 3”], which you can listen to here in a dramatization provided by X Minus One in 1955)], especially so since the turn of the 19th century when America’s cities and industries began to grow and expand all over the country. It’s obvious that cities have problems and tend to dehumanize people (the plasticity of Los Angelinos referred to above), or if enough of them are crowded into a small enough space (see Theodore Sturgeon’s classic “The Other Celia” from the March 1957 issue of Galaxy for a better example of how cities dehumanize people on a personal level), but the attendant crime and other urban problems occur in any city, anywhere, regardless of their size and to one degree or another. Again, this is nothing new or revelatory. But the author also attacks the suburbs when our narrator relates that, when referring to the suburbs, “All the grey places that cannibalized the cities are gone.” So now it’s both cities and suburbs that are bad. Then our narrator tells us that people who used to work in some form of commerce or industry have now seen the light. Again, to wit: “The farmers are experimenting, making new things out of the soil. They’ve made a plant that tastes like chocolate grow in the Midwest. It’s creamy and sweet so you can eat the fruit straight. It tastes slightly nutty as it dissolves in your mouth. A used car dealer from Troy, Michigan, developed it. Horticulture had always been his hobby, and it became his life after Detroit leveled his home and killed his family. He lost everything, but the cities are full of chocolate.”

The naive, shallow logic of youthful (liberal) idealism here is inescapable, for it takes science and chemistry and laboratories and distribution (and highways and trucks and electricity and for all intents and purposes the same basic infrastructure the author seems to be against when it comes to the evils of modern industrialized life in general, and cities in particular, and has them destroying themselves and murdering the people who inhabit them) to enable this hoped-for (by the author) change in direction. But all we see as a positive result in the author’s scenario are ruined cities now selling “fresh” produce (I hate the “unfresh” kind at my local open-air market) instead of cars in the marketplace, and by golly they’re “full of chocolate [fruit]”–but they’re sweet and creamy and taste like nuts? I’ll give the story that. Nuts.

If you share the author’s views on this subject then fire up another one and have a big bowl of M&Ms handy, for you’ll enjoy this story. Otherwise I’d pass on this crude, poorly reasoned little screed.