by

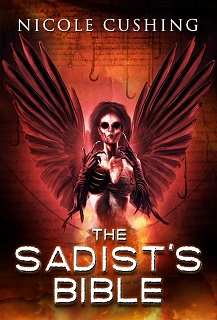

Nicole Cushing

(01Publishing, April 2016, 87 pp.)

Reviewed by Jeb Kinnison

“Do u really think ur ready 2 die? I don’t want u chickening out on me.”

This is the first line in Nicole Cushing’s new novella, The Sadist’s Bible, following up on her Bram Stoker Award-winning novel Mr. Suicide.

Trigger warning: extreme lesbian sexual imagery, torture, blasphemy. Unlike traditional horror, her writing relies on explicit imagery; where a traditional horror writer would leave the disgusting details to the reader’s imagination, Cushing dwells on them, in the splatterpunk subgenre’s tradition.

Ellie is a middle-aged childless woman married to a devout Christian man in southern Indiana, working in sales and secretly attracted to younger women. She feels guilty about her disloyalty to both her husband and her God but wants more, and starts to open up her lesbian feelings on online social networks. She stumbles on a site bringing together those who want help to commit suicide called “The Buddy System – Putting the ‘pair’ in despair,” where she meets Lori, a young woman who excites her lust and pulls her into a plan to commit suicide while having sex.

It’s hard for a mentally healthy person to imagine being suicidal enough to want to kill yourself while still being interested in kinky sex. But a great writer can pull off this examination of diseased mental states, making the implausible seem believable – a suspension of disbelief. Cushing is trying to bring the reader into the fevered dreams of her characters, and she succeeds – but will you want to go where she takes you?

The young woman Ellie meets online, Lori, at first appears to be insane. She believes her God – a primitive deity of chaos – has been raping and torturing her, and fathered her defective son, Joshua. When she was pregnant, her parents insisted she keep the baby, who has clung to life despite anencephaly and is taken care of by her parents.

[Spoilers follow.]

We at first assume Lori is an unreliable narrator. The story is about halfway over when the reader hears directly from Lori’s cruel sadist of a God, and soon Ellie, too, is experiencing manifestations of His ability to intervene in events….

Traditional horror stories leave a trail of breadcrumbs back to reality, where the fantastic elements are explained as existing in a character’s mind, or as the result of a malevolent supernatural force. This is not one of those stories; the reader is asked to accept the reality of this sadistic God. Even folie à deux (the psychological phenomenon of shared madness between partners) is ruled out, with a folie à Deus (the madness of God) animating the events. This is a fantasy detached from and hostile to reality, relying on notes of blasphemy, disgust, and sexual transgression to bludgeon the reader.

Which is what makes this almost YA – the blasphemy is only interesting to those young enough to have not seen it before; the sex and torture scenes are no longer shocking if you’ve seen similar material used in the service of a worthier story. Since this is a review for general readers, I can’t quote any of the intentionally transgressive, explicit sexual and religious imagery, but it feels like a cry for attention.

Philip José Farmer’s porn novel Image of the Beast (reviewed here) and William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch were published when such material was new and fresh. It isn’t now, after decades of explicit sex and violence in mass media.

The characters in The Sadist’s Bible are all unlikable. Without a character a mentally healthy reader is comfortable identifying with, the story is unpleasant to read and unrewarding. Popular horror relies on at least one character who serves as the moral center, threatened by evil and disorder but fighting to defeat it – Stephen King’s The Shining had the boy, while Thomas Harris’ Silence of the Lambs had Clarice Starling to serve as the morally strong foil to Hannibal Lector’s evil serial killer. Great psychotic or evil characters need a frame of external reality and morality to contrast. The “normal” character does not have to win or even survive – but without the drama of a struggle, there’s little reason to stay involved in the story.

The contrast between good and evil, between mental health and insanity, between order and chaos, between purity and contamination, is what makes for a good horror story. Cushing is an excellent writer who missed an opportunity to make her work more accessible by framing her two main characters as suffering a folie à deux, allowing the reader to keep their more comfortable moral framework. Having the sadistic God character speak directly to the reader implies a morally disordered universe where, as He suggests in several messages, “The arc of the universe is long, but bends toward moral degeneracy,” a perversion of Martin Luther King’s speeches, where “The arc of the universe is long, but bends toward justice,” itself paraphrasing Theodore Parker, an abolitionist and Unitarian minister who died in 1860.

A policeman who had dealt with the younger Lori makes a brief appearance. His grounded-in-reality, normal point of view could have been expanded to frame the story of the two doomed lovers, or Ellie could have been strengthened as a character to more fully resist the demon-God and break free of His clutches. But the story is weakened by its depressing lack of conflict – Ellie and Lori plod toward their fate of endless sexual torture in the demon-God’s Hell without putting up much of a fight.

Iain Bank’s Hell and torture scenes in Surface Detail, which are similarly gory and sexualized, were set inside a computer simulation designed as punishment for criminals – The Sadist’s Bible is a torture simulation for the reader as designed by the author.

If you like this sort of thing – sexual torture and mutilation, dwelling on the disgusting and profane – Cushing’s writing is powerful. But stories with no heart should come with warning labels.

Jeb Kinnison discovered science fiction in second grade, starting with Tom Swift books and quickly moving to Heinlein juveniles and adult science fiction. He studied computer and cognitive science at MIT, and later did supercomputer work at a think tank that developed parts of the early Internet (where the engineer who decided on ‘@‘ as the separator for email addresses worked down the hall.) Writing science fiction with the Substrate Wars series.

Links: http://SubstrateWars.com , http://JebKinnison.com

Latest book: https://www.amazon.com/Shrivers-Substrate-Wars-Jeb-Kinnison-ebook/dp/B018HTK76W

The Sadist’s Bible

The Sadist’s Bible