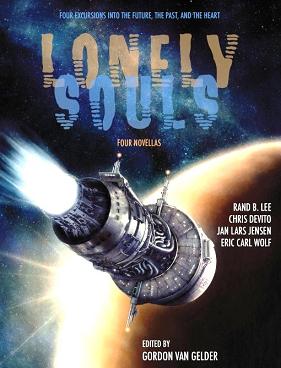

Edited by Gordon Van Gelder

(Spilogale, Inc., May 1, 2013, e-pub, $5.99)

Reviewed by Matthew Nadelhaft

Lonely Souls collects four novellas that didn’t quite fit into The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. The title of the collection highlights the presence of these novellas in a stand-alone collection as well as hinting at a common theme of loneliness. But more, it illustrates something of the problem of novellas, a strange and not-very-well-understood art form. The length of the novella makes it difficult to collect more than a few in one anthology, making the sustenance of a theme, without sacrificing diversity, problematic. That issue raises a more important question: what is a novella, other than its length? Is it possible to define a novella without describing it as “longer than a short story but not a novel”?

Well, using the inductive principle, I’ll try to come up with an understanding of the novella by looking at the ones included here, and asking what they do, or fail to do, that we wouldn’t find in stories or novels. The first inclusion is “Goliath of Gath” by Jan Lars Jensen, which begins with the Biblical story of David and Goliath, from Goliath’s point of view. The idea of giving a background and life to an unexplored figure from the Bible appealed to me, especially one meant to be nothing more than a heavy, a one-trait villain. Goliath, even more than most Biblical characters, is simply an allegory in flesh, a principle waiting to be overcome by a more compelling principle.

Jensen’s piece succeeds at creating of Goliath a genuine literary character, without actually humanizing him. Goliath is one of the last of the Anakim, giants from “the early days of the world” living among the Philistines. Goliath begins as the runt of his family, alienated from his own people by his lack of their defining trait. He tries to find himself at the furnace where his brother Himal works iron, the secret of the Anakim. Unfortunately, Goliath’s response to loneliness makes him look like a sulky brat, which gets in the way of him becoming a likeable or interesting character. Some of the minor figures in this story, such as Himal and the Philistine youth Map, are well-drawn and compelling, and even the bully of Goliath’s youth (it’s a neat twist to give Goliath a bully!) later emerges as a two-dimensional figure.

Likewise, the depiction of the life and culture of the Anakim is never very satisfying. We don’t learn much more than that they are peace-loving, particularly contrasted with Saul’s warlike rabble and the Hebrews who hunted the Anakim to near-extinction, a characterization that hints of anti-Semitism. In truth, the Hebrews as depicted in Deuteronomy are a vicious lot, but a story which goes so far beyond Biblical characterizations didn’t need to take Deuteronomy at its word on the Israelites, either.

In the end, “Goliath of Gath” is an intriguing project that falls short because it doesn’t quite go far enough into its own premise: it gives Goliath a story, a people and a character, just not rich enough ones. Ironically, Goliath seizes the complexity latent in his depiction only at the end of the story, with his death. That ending makes for interesting speculation about the nature of fictional characters, particularly of villains, of their inevitable ends, and of the Bible. But a more satisfying Goliath and a better drawn people would have been an even greater pleasure, and could have happened in a work of almost any length.

Eric Carl Wolf’s “The Demands of Ghosts” posits an unnamed narrator in an even lonelier position than Goliath’s. Our narrator, a “retired” hitman, lives on Toom, an outback planet that could hardly be more bleak. Even the description of Toom becomes monotonous; the story begins with the narrator exploring his new home, learning about its people, and we travel with him, sharing his sense of repetition, of futility and boredom. The people are curt and phlegmatic, the landscape dreary, the environment unhelpful. About the only bright spot the narrator can find is a woman named Una. Una is of indeterminate age and her particular brand of disinterest intrigues the narrator.

As the narrator and Una slowly, almost grudgingly, become acquainted, the story begins to suffer from what I found to be its main problem. It seems largely unsure exactly who the main character is: Una or the narrator. Large sections of the story consist of Una telling the narrator about her past; unfortunately, it just isn’t that interesting. The narrator’s past, on the other hand, is more interesting, but doesn’t make him any more sympathetic, and the emotional resonance of the story’s conclusion was undercut, for me, by how neatly it fit in with the redemption/hitman-with-a-sentimental-side trope(s).

This story, I think, would have been better in a shorter form: the descriptions, although rendered in clean and polished prose, became intrusive and the lack of a firm sense of who the main character really was proved a distraction. Both these problems would have had a lesser effect in a shorter form, which tells me something about novellas: their length should not be determined by how much background or description needs to be relayed, but by what it takes to unfold the story properly.

In “One Day at the Zoo”, by Rand B. Lee, a young girl is dumped by her mother into a bear exhibit at the zoo. As 12-year-old Eulie recovers in hospital, her carers – Doctor Ann and Nurse Arturo – struggle to learn why Eulie’s insane mother first abducted her from her father, then kept her a tortured prisoner for years before attempting to kill her. The story is written engagingly from Eulie’s perspective. The narrative recounts the abuse visited on Eulie by her mother effectively, without melodrama or pretension.

Eulie is abused by her mother in part because she has psychic abilities – what Eulie has learned, touchingly, to call her “monster power.” Her father is a scientist, and it is from his lab and experiments that Eulie’s mother thinks she has “rescued” the child. There is a tension between wanting to see Eulie freed from the clutches of her mother and worrying that a return to her father’s care might not be much better. Even sympathetic Doctor Ann is aware of the danger, but most of the conflict comes from within Eulie’s mind, from her fears of her mother and her fear of herself, and her uncertainty about the future. Only Eulie’s hospital carers seem completely sympathetic and agenda-free, and even their philanthropy is challenged when Eulie’s powers finally manifest.

There are places in the story that suffer from over-explaining and there are characters whose voices are either unformed or inconsistent, but on the whole it is well-written and engaging. The weakest part was the ending, which is too drawn out and takes us in too many directions – including back to the beginning of the narrative and far beyond it. The novella could have ended very satisfactorily several paragraphs before this wind-up begins.

The emotional impact of “One Day at the Zoo” is made possible in part by its length – any longer and it could have become maudlin, much shorter and Eulie might not have been as well-sketched a character, her predicament less believable. Another clue to understanding the novella emerges here. Characters may take time to develop, but no story can be any longer than its character depth allows.

In this collection’s final entry, “Final Kill,” Chris DeVito has created a monument of repulsiveness. Reading it literally made me queasy. It’s a complicated, far-future story of drug companies, venture capitalism, assassins, and immortality – not to mention epic immorality. The writing makes me think of Richard Calder (although with shorter sentences, thank God) trying to out-noir Richard Morgan, or even James Ellroy, but without Morgan’s obvious humanity. From the beginning we are presented with a torrent of murder, dismemberment, torture and fetishized sex, all described in excessive, clinical detail.

The narrative cuts back and forth between a handful of (equally repugnant) characters including an assassin who thinks nothing of mowing down streets of bystanders during a fire-fight, yet is apparently intended to be the story’s most laudable character; the barely pubescent young girl he tries to kill and tortures and who, inevitably, becomes attached to him; and a couple of businessmen distinguished primarily by their locations on the pecking order and their respective sexual fetishes.

The overall effect is near overwhelming. It’s a morally bankrupt far-future obsessed with money and gratification, and the immortality plague unwittingly unleashed by the financiers only makes things worse. There is technical skill in the writing – for instance, using the present tense to increase the visceral impact of the story’s many atrocities – but the application of too many of the writing equivalents of CGI comes off as more pretentious than dazzling, particularly when harnessed to the cause of shock more than awe. DeVito does succeed in making immortality look quite undesirable, but he doesn’t make anything else look any better.

This story might have been better served stretched into a novel, in which form the myriad points DeVito seems interested in making about morality and mortality; capitalism, greed and religion; the growth of culture and the growth of the individual; and old age and youth could have played out without the overabundance of technique and the bludgeoning brutality. Presented in the length of a short story this narrative would have been nothing but flash, but in an even longer form its effect could arise out of the ideas presented within, not just from a cacophony of bullet wounds, flayed skins, and genitals.

In the end, we may not emerge from this brief interrogation with a definition of “novella” that doesn’t depend on its length, and that length is inevitably understood with reference to short stories and novels, but what of it? We understand all terms with reference to the ones most like them. What we must take from this collection is an idea about the merits of these novellas. And to some extent all these novellas may be suffering from an inevitable comparison – I just reread Katherine Kressman Taylor’s “Address Unknown,” to my mind the greatest novella ever written. But the lesson Kressman Taylor taught in 1938 remains true. The novella, properly executed, is not a novella because it works best at that length, but because it could only work at that length.