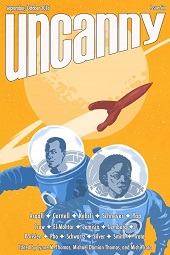

Uncanny Magazine #6, September/October 2015

Uncanny Magazine #6, September/October 2015

Reviewed by Nicky Magas

Nothing good ever happens to Gary. His mother doesn’t care about him, he doesn’t have any friends, and life just never seems to throw him a bone. So when an alien space ship crash lands nearly on top of him in “Find a Way Home,” by Paul Cornell, Gary sees his opportunity to become famous, maybe even land a spot on TV! But with the RAF chasing after him and a tiny alien to protect, it’s soon clear that Gary can’t realize his dream on his own. It’ll take a lot of luck and the help from some of his schoolmates before Gary can achieve all that he really wants.

Paul Cornell gives readers a humorous spin on the alien crash-landing story in “Find a Way Home.” Populated with bumbling military personnel, realistically obstinate children and an alien that just wants a quiet getaway, this story is much easier to believe than a child-instantly-befriends-alien narrative. While parts of it seemed rushed, overall it’s fun middle grade science fiction packed with danger, suspense, and clever children. As one would expect, by the end lessons are learned and friendships are forged and everyone goes home happy.

In Isabel Yap’s “Oiran’s Song,” Akira struggles to fulfill his elder brother’s final wish for him: simple survival. Travelling as an errand boy in a secret division of the Tokugawa army, Akira suffers every conceivable abuse at the hands of the soldiers, but it’s nothing more than he’s been used to since his village was burned and he and his brother were forced to take refuge in a brothel. The coming and going of high class prostitutes in the camp is likewise nothing new to Akira, but this new one is different. She doesn’t fear the same way the other ones have. Her skin is almost as pale as the snow, and something burns in her eyes, something angry and not quite human. When the bodies start piling up, Akira isn’t sure entirely what he feels, but he knows that escape has never been an option in his life.

“Oiran’s Song” comes with a trigger warning for sexual violence, but in the context of the story it is tastefully written. The Japanese setting is smoothly depicted with few cultural or linguistic linchpins in the narrative to trip up readers who don’t have a keen understanding of Japanese mythology or language going in. The second person perspective at times felt needless, as neither the second person point of view nor the structure that houses it adds much more to the story that couldn’t be accomplished in the third. While the second person does manage to put the reader uncomfortably close to the emotions and unsavory theme of the story, it also often makes the narrative’s tone sound accusatory. “Oiran’s Song” maintains Japanese story telling conventions through to the end, and while the final scene feels somewhat drawn out, it nonetheless ties up the whole narrative very neatly, with clear, succinct imagery and comfortable closure.

What do you do when your sister is far, far away, completely unreachable, and the only connection you have to her are the letters she sends and the pieces of a train that she encloses with them? If you’re the protagonist of Liz Argall and Kenneth Schneyer’s “The Sisters’ Line” you take those pieces and build a full sized train out of them. You don’t know how to build a train, or even if the completed train will be able to take you to where your sister is, but with the help of a small child with a big imagination, at the very least you won’t be alone.

This short piece of surrealist fiction is brimming with metaphor. While the reader never quite understands where, when, or in what state is the missing sister, the impression that she is entirely unreachable is evident. The pieces of the train that come with each letter function as the only line between the two sisters. One has been left in poverty and one has, if the story is taken at face value, been abducted or something else, stretching the metaphor, and has moved voluntarily beyond the situation that the two once shared. It is even possible that the wayward sister is dead, though these speculations aren’t crucial to the story. What does beg deeper scrutiny is the role that looking at a problem from a different angle plays in finding the solution. The protagonist spends so much of her time focused on the surface value of each fragment of the train that she fails to see that they are malleable and can be shifted, rearranged and merged to create a working conveyance to her sister. The reader isn’t given much closure in the story beyond the understanding that the protagonist, with the help of her child neighbor, is able to escape a situation that she is unhappy with, and find the sister—the missing piece of her life—that has been gone for far too long.

Glitter frogs are everywhere in Keffy R. M. Kehrli’s “And Never Mind the Watching Ones.” They cover the ground, the walls, and people’s clothes. Nothing can keep them out, but they don’t do much harm, aside from being in the way. They just sort of observe people. Stranger still is that no one really knows where they came from. Maybe they’re aliens, or maybe they’re government spies. They more or less look and behave like regular frogs, except for the circuitry—and their uncanny ability to know what people are thinking. There are conspiracy theories, of course, and some of them even have weight, but no one pays them much attention. And certainly no one makes any connection to the frogs when four troubled teens go missing without a trace, without a word of warning, to join the frog mother ship somewhere high above Earth.

“And Never Mind the Watching Ones” starts with a bang and keeps the reader hooked through to the end. Between beautiful imagery and concise prose is a story about leaving and being left behind, forgetting and being forgotten. The present tense narration lends the story immediacy, which it needs when the large cast of characters begins to buckle the narrative near the middle. It fortunately never quite reaches the snapping point, however, and leaves readers dangling on an ambiguous ending, not quite sure who they should be rooting for, or what outcome is most favorable for the characters. There’s a lingering taste of tears and tragedy in each scene that makes the story bittersweet and easily palatable. Furthermore, the tiny bits of exposition told via social media updates are a nice touch in reminding readers that these are all teenage protagonists. In all it’s a very well crafted story, from beginning to end.