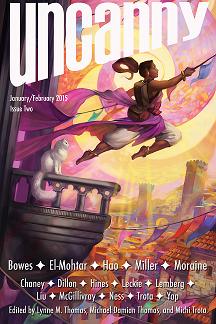

Uncanny Magazine #2, January/February 2015

Uncanny Magazine #2, January/February 2015

Reviewed by Charles Payseur

Lao Dao, a waste processing technician, makes a perilous journey through a mechanical city in Hao Jingfang‘s “Folding Beijing.” From Third Space, the poorest of three cities that live overlapped, folded on top of each other, Lao Dao agrees to carry a message to First Space, where the most wealthy of the city live, in exchange for money to send his adopted daughter to a decent kindergarten. Not exactly a young man anymore, Lao Dao still finds the strength to steal his way to First Space and deliver his message, though things don’t go nearly as smoothly as he intended. Caught, he fears the worst until he is saved by a man who grew up in Third Space but was promoted out. He’s brought to a sort of party, and there Lao Dao learns that his life, that the entire basis of the city, is an illusion, but that there are no easy answers when dealing with economies, with poverty, with employment and technology. A moving story, it manages to keep things interesting, makes Lao Dao into a man not broken by his situation, by the system that oppresses him, and concentrating instead on the things he can do. Ultimately triumphant, the story offers a complex view of a complex city and does it with style.

Sam J. Miller puts a supernatural twist on the Stonewall Riots, an important event in the gay rights movement, in “The Heat of Us: Notes Toward an Oral History.” Told as a journalist compiling interviews from various witnesses present at the scene, the story plays out differently than history, and the resistance the police find in the Stonewall comes in the form of a fiery blast instead of fist fights and projectiles. Weaving together the narratives of the few people most prominently there, most responsible for the somewhat magical fire that burst forth, the story does an excellent job of capturing a moment in time, the injustice of the police, the desperation of the men and women trying to find a place to be. And through it all there is also the story of the journalist writing the piece, and guilt and regret and a call for change that can easily be brought forward from the past and unpacked in the present.

Pants pockets, coat pockets, cardigan pockets: all act as conduits for objects, and for something a bit more, in “Pockets” by Amal El-Mohtar. At first, Nadia isn’t sure what to think when she starts pulling strange objects out of her clothes, objects she knows don’t belong to her, objects that she has no idea what to do with. After confiding in a friend with a scientific eye, though, she finds out that her pockets are some sort of gateway to elsewhere, that items arrive in her pockets from somewhere else. It does not, however, clear up why it is happening. It’s something that Nadia wonders until she meets Warda, whose pockets take items instead of giving them. Between the two of them they make some sense of what is happening, and Nadia gains a deeper understanding of herself, of the world, and of her pockets. Short and sweet, the story borders on some big ideas while keeping things nicely grounded in Nadia’s perspective. Perhaps a bit sappy at the end, the writing was solid and the message warming.

A man and his doll must flee a politically roiling New York after some ill-thought-out comments on his blog make him a target of violence in “Anyone with a Care for Their Image” by Richard Bowes. Told by a man completely outside humanity, or at least outside the uglier aspects of it, the main character thinks the troubles bubbling up to open conflict in the city are inconsequential as he goes about with business as usual on his blog. But he chooses the wrong time to be flippant, the wrong place to be crass, and soon finds himself having to flee the city to more comfortable seas, sure that time will allow him back in to flourish once more. An interesting look at how entertainment and the internet moves in cycles, and how the privileged can afford to wait out unrest, the story is short and vaguely unsettling and worth a close reading.

In “Love Letters to Things Lost and Gained,” Sunny Moraine tells the story of a woman who survived a car crash to find her arm replaced with a top-of-the-line, artificial limb. Integrated into her nervous system, she can feel through it, can use it as she could a normal limb, and yet its foreignness bothers her, as does the fact that she wasn’t given a choice to receive the prosthetic. And as she wrestles with her new situation she examines what repels her about her new limb, and just as she becomes a little more comfortable with it she’s offered a treatment that would actually regrow her arm. Challenging the idea that real flesh is any better than a prosthetic, the woman finds a certain peace with her new limb, with her new situation. Told with a striking look at what makes us human, the story works thanks to beautiful prose and a complex main character, and I strongly recommend giving it a look.

Charles Payseur lives with his partner and their growing herd of pets in the icy reaches of Wisconsin, where companionship, books, and craft beer get him through the long winters. His fiction has appeared or is forthcoming at Perihelion Science Fiction, Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, and Fantasy Scroll Magazine, among others. You can follow him on Twitter @ClowderofTwo