“Palingenesis” by Megan Arkenberg

Reviewed by Brandon Nolta

When a story begins with some verse from Inferno, one might expect something phantasmagorical, allegorical, or just downright nasty, but Megan Arkenberg’s “Palingenesis” has something completely different in mind. The narrator, Joan, is a haunted woman: haunted by her ambiguous feelings regarding her son Blair—to the extent of referring to him as “they”—who vanished one day; haunted by the work of the mysterious artist Yelena Hersh, whose paintings of Blair offer the most vivid evidence of his existence; and haunted by the phantoms of the forest, which may be magical creatures or maybe aren’t there at all. Whether Joan’s fears or perceptions are real is beside the point, even to Joan; the reality of Blair’s absence, and Joan’s guilt, is all that matters. Thick with classical allusions and vibrating with loneliness and grief, “Palingenesis” feels almost more like a tone poem than a traditional story, but works beautifully in that space.

In “The Fifth Gable,” Kay Chronister tells the story of four women who share a house and create children from scratch using different materials and methods: growing them in the earth, building them from bits of wire and mechanical parts, as you do. Set during an unspecified war (although WWII is implied), the story follows a lonely woman named Marigold as she approaches each of the women in turn, who each occupy a gable in their joint abode, to ask for a child. For their own reasons, each woman agrees, and how Marigold deals with each of these children, and what she eventually does in the fifth gable, I leave for the reader to discover. This may be the oddest of the stories in this issue, but Chronister evokes each character with warmth and precision, and the shared emotional life of these women ultimately puts the strange situation—picture Grey Gardens if Shirley Jackson and Charlotte Perkins Gilman were sisters—into a sympathetic context.

For those who enjoy stories that taste a bit like Kafka, Kostas Ikonomopoulos’ “The Block” may satisfy that urge. In an unnamed city, a perpetually mist-cloaked tenement stands, its residents mostly retired from life and grimly holding onto what life and secrets remain to them. Among them is Majarek, a one-armed war hero whose celebrated past holds a secret that he cannot bear to contemplate, much less have revealed to his estranged son or his neighbors in the block. At least one other person knows this secret, however, and he has no qualms about letting it out. Written without dialogue and in a formal style that recalls late 19th century English literature, “The Block” occasionally gets lost in its own stylistic labyrinth, but the language is unfailingly lovely, and the ending manages to trade in the story’s surrealism for a deadpan poignancy.

To wrap up, Michael McGlade brings in “Another Beginning,” the only story of this issue with a modern feel. Ógán, a university student in Belfast, discovers his fiancée in flagrante delicto with his best friend, and commits suicide shortly thereafter. Reincarnated as a magpie, Ógán works as a psychopomp, shepherding souls to their destinations after death, and bringing those set for reincarnation back to the mortal plane. All’s well and good, until one day, Ógán finds himself face to face with someone he hadn’t expected to see for a while yet, and makes an unexpected choice. Interspersed with facts and asides that switch points of view on the reader, McGlade’s story is not as innovative in its structure or perspective as the author may hope judging from the interview with the author included after the story, but McGlade writes with an appealing lightness to his tale of reincarnation and grace, and while it isn’t the most accomplished of the group, it is easily the most fun.

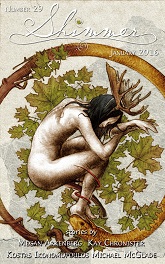

Shimmer #29, January 2016

Shimmer #29, January 2016