Reviewed by Douglas W. Texter

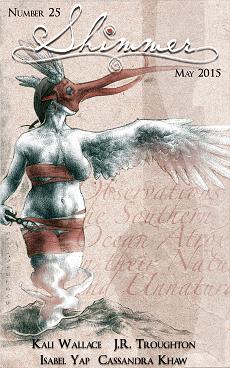

In “The Proper Motion of Extraordinary Stars,” Kali Wallace presents a nineteenth-century framed narrative. Aurelia, a female explorer and scientist in an age in which career paths for women pointed to the position of governess, not that of naturalist or astronomer, arrives on the near-Antarctic Asunder Island in the company of her aunt, Theo. A woman on a mission, Aurelia has come to the island to use its observatory to study the Summer Star, which “moves unlike stars around it. It moves with them too, rising and setting every day and through all the seasons, but it’s also moving between them.” While her aunt remains on the ship that delivered the pair to Asunder, Aurelia spends time visiting with Constance, who is a cross between a human and an Atrox. The Atrox are birds that live under the island’s surface. During her time with Constance, who has one arm that is actually a wing, Aurelia learns that Constance has a fiancé who serves on a whaling ship. Aurelia doesn’t believe for a second that the young whaler will ever return to his betrothed. In addition, Aurelia learns that her mother, Letitia, shortly after she married Aurelia’s father, once visited the island and met Constance. Much of the tale concerns the story about Letitia that Constance tells Aurelia. Although this tale is beautifully written, it disappointed me. Aurelia gains knowledge about her mother, who along with her father, died in India when Aurelia was a child, but this knowledge seems somewhat superficial: the mother was unhappy with own mother and with her husband. Who is not unhappy occasionally with one’s parents or partner? This unhappiness, concerning as it did a very privileged person, didn’t impress me. Thus, the payoff of the framed story seemed to be pretty low stakes. In addition, other than Aurelia’s desire to prove “the men of the Royal Society” wrong and to humiliate Lord Petterdown, whose father had constructed the telescope on the island, there didn’t seem to be wider societal consequences to this astounding discovery.

“The Mothgate,” by J.R. Troughton, presents a kind of literary Escher staircase. When the tale opens, the teenaged Elsa, a foundling, and the seemingly ancient Mama Rattakin, who has both a ruined hand and a crippled leg, stand in front of the Mothgate on the evening of a September 19th, which is Elsa’s birthday. Through the Mothgate, another realm’s monsters—such as witika, tallemajas, pollogrubs—enter our world. Mother Rattakin, who has taught Elsa to use a rifle, exists as a gatekeeper, working to bar the devilish beasties. We learn that these kinds of teams—a mother and a foundling—have been working for a long time at the task of patrolling the gate and seeking a way to close it. Eventually, Mother Rattakin crosses over to the other side to see if she can permanently slam shut the gate to our world. She warns Elsa not to follow her. Years later, though, on another September 19th, Elsa sees Mother Rattakin through the gate and goes after her. When both women wander on the other side, a kind of battle takes place with another nasty, the worst of all: a brasskarl. During her time on the other side of the Mothgate, Elsa suffers terrible wounds to one hand and one leg. One might now see that this story takes on a cyclical nature. The circularity and the fine writing here give “The Mothgate” a lyrical beauty. I felt at times as though I were reading a kind of poem or fairy tale. This circularity is double edged, though. It both haunts and frustrates. We don’t end very far from where we started.

In “Good Girls,” Isabel Yap presents a tale of some very bad girls, inmates of the Bakersfield Good Girl Reformation Retreat, which functions as a combination of a juvenile-detention facility and a self-help/recovery center for quite wayward female youngsters. Sara, a teen from suburban Pleasanton, dropped her sister’s infant and developed an obsession with thinking about ways to hurt babies. She becomes concerned about her own obsession and believes that the key to saving all the world’s infants is to jump out a window and fly. Her Filipina roommate, Kaye, is something else entirely: a manananggal, a kind of vampire that feeds on unborn children. A manananggal can detach its torso from its legs and fly off into the night on a feeding expedition. The story weaves between two points of view: Sara’s third-person limited and Kaye’s second-person POV. Kaye’s POV is especially powerful because it details her flights through the nights of Manila, with its poverty and decadence. These scenes are hauntingly beautiful. This story, the strongest in this issue, concerns obsession, hunger, and friendship. I recommend it.

In “In the Rustle of Pages,” Cassandra Khaw presents a story about an old woman, Li Jing, whose husband, Zhang Yong, is dying. Their grandchildren want to put the grandfather in a nursing facility and have the grandmother rotate residence in their homes. There’s nothing particularly out of the ordinary here. Or is there? In this world, because of a disease, people turn into buildings when they die or perhaps even before they expire. As he dies, Zhang Yong has “tiling on the walls of his heart,” and “stairwells” bud “in his arteries.” This story slightly confused me. I’m not sure I completely understand why people turn into buildings here, but I found the conceit very interesting. And the love story between two probable octogenarians was heart warming.

Shimmer

Shimmer