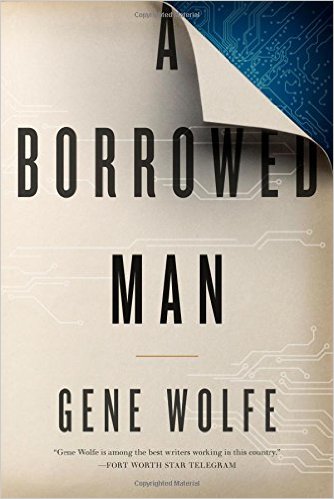

by

Gene Wolfe

(Tor, October 2015, 300 pp., hc)

Reviewed by Dave Truesdale

The versatile, agile mind of Gene Wolfe never fails to come up with something different with which to capture and hold reader interest. Each new novel, regardless of genre—science fiction or fantasy or anything else—is guaranteed to have the light of Wolfe’s imagination illuminating areas of genre we just knew held no secrets or surprises. Yet he continually finds shadowed or neglected corners others have overlooked—or perhaps superficially explored, at best—and with uncanny grace and aplomb reveals their existence in full light and only as he can. Such, I believe, is the case with A Borrowed Man.

I found the story to be a well-designed 50/50 marriage of 1930s pulpish SF and the now classic noir detective murder mystery formula first given us by Dashiell Hammett in the 1920s and early 1930s (with his Continental Op and then Sam Spade hard-boiled detectives) and then copied and made popular by many another noir detective novelist. To be more accurate, however, I wouldn’t consider The Borrowed Man a noir novel in the classic sense (dark, brooding, gritty, scenes drawn in shifting shades of light and dark throughout), though the rest of its formulaic trappings certainly fit the mold. And in place of the hard-boiled detective (Sam Spade, Mickey Spillane, Philip Marlowe, et al), we are given a lead character (about which more in a moment) filling the detective role more in the soft-boiled detective vein (The Saint, Nero Wolfe, Nick Charles, et al).

Background and setup for the science-fictional half of the novel finds us in the 22nd century. Technology has now given a smaller, more affluent and apparently less-stressed world population (one billion, which is in the ballpark of actual government 1920s population stats) many comforts, mostly of a benign nature (though this world has its dark elements as well, mostly in the background), one of which is the aircar—here with flitters and hovercabs—that SF has dreamed of since its earliest days. Unique to The Borrowed Man and from which the novel derives its title, are fully functioning clones (via the DNA from once-living authors) embedded with the last-uploaded personalities of a book’s author. These clones are shelved in large libraries and can be checked out—borrowed—as would any book in one of today’s libraries. Having an author’s work preserved is in itself valuable, of course, but to be able to consult, to pose questions of the actual author is something else again. But what a whacky idea! Why not have the last author personality upload on a small disc along with his or her book or books, rather than (when not in use) a life-sized human clone shelved in unending horizontal cubicles in what must be an immense library? And the same arrangement in branch libraries as well? How would this really work? Well, some of the details are alluded to with some seemingly reasonable explanations (but not in any depth and only to a certain point), but just as many of the bizarre, crazy ideas in SF pulp magazine fiction were wild and imaginative and “really cool” were explained with handwavium science, or were just plain impossible according to the laws of physics, it was the boldness and audacity of the idea that endeared them to the hearts and minds of readers. So too, I imagine, is the case here, with the offbeat and somehow emotional appeal of libraries not only shelving books, but the closest we can come to checking out the actual authors themselves by way of human clones. And, let us not overlook, making this high-tech advance affordable to many and profitable for the libraries (clones can give advice and information in-library for one fee, and be rented out—borrowed—for a much higher fee). Which also reveals a piece of the puzzle as to what kind of future society we’re being given here. Gene Wolfe focuses reader attention only on details he chooses to reveal, in order to implant in the reader’s mind’s eye the impression of the world (visual and emotional) he wants us to see. And right from the opening pages he has our attention.

Background and setup for the 1930s-style detective murder mystery half of the novel takes us immediately to the clone of deceased writer E. A. Smithe on his shelf in the Spice Grove Public Library who, in familiar detective novel fashion, is telling his story in the limited first-person point of view. (This is a familiar point of view character for Wolfe, for just as in his 1986 novel A Soldier of the Mist we have the brain-damaged Greek soldier Latro losing is memory each day and then finding ways to remember each previous day, here we have the clone Smithe whose history of the world goes back only so far as his last personality implant, and as he catches up on his world following being checked out of the library, so too is the reader introduced to the world through his eyes.) And it is from Smithe’s point of view that we learn that Colette Coldbrook, the daughter of a wealthy scientist who has gone missing and has been proclaimed dead, has come to check him out of the library for a possible clue to her father’s presumed demise. Following her father’s death, her brother, Conrad, Jr. had their father’s safe opened only to find a copy of Smithe’s SF thriller Murder on Mars. An odd item to be placed in the safe by itself (no family jewels or anything else of worth), it must hold important information of some sort relating to her father. But what secret could a simple, rather run-of-the-mill novel hold, if any at all? Thus, the secret Murder on Mars presumably holds becomes the McGuffin, the plot device fueling the events of the story. So Colette’s investigation begins at the only place it can and with slim hope, by questioning the clone of the late E. A. Smithe, author of the book. Being an almost-human AI (human in every way it should be noted, save for the AI aspect, though not legally recognized as such), Smithe and Colette soon form a close professional relationship as Smithe is borrowed from the library and follows Colette’s lead in trying to unravel the mystery, for the supposed clue the book holds may mean immense wealth for whomever discovers its secret.

The story now sees Smithe housed in the Coldbrook mansion while he investigates and explores the manse for possible clues, including the fourth floor locked laboratory of Colette’s scientist father, which he clandestinely and with much effort manages to breach. What Smithe discovers is important to the plot, so without giving away any spoilers I will say that it reinforces my view that the discoveries made therein lend themselves strongly to their origins in 1930s and ’40s pulp magazine SF.

The front story itself pays respectful homage to, and has fun with, the now classic detective murder mystery, employing several familiar elements. Already mentioned is the McGuffin which sets everything in motion. Add to this we have unsavory characters also in search of the secret Murder on Mars holds, a kidnapping, old man Coldbrook’s decision before his death to replace the human household servants with advanced robot servants, a love interest as Smithe meets with the reclone (a borrowed woman) of his deceased wife and poet, and oh, yes, another murder. There’s more, of course, with the usual misdirection and dead ends, but how it all plays out makes for an intriguing surface story worthy of the heritage it honors from both its pulp SF and classic detective roots.

There has been an off-and-on resurgence in recent years (see the 2007 Gardner Dozois edited anthology The New Space Opera, for but one example) where certain sub-genres of SF once out of favor—or which had run their course decades past, all veins of originality believed to be exhausted—attempt to reinvent themselves, and do so “but with modern sensibilities” for a new generation of readers. Gene Wolfe’s A Borrowed Man is a rejuvenating reminder of that glorious and (dare I say it) naive time when SF was new, the dreams were large, and the ideas wild; and when the classic detective novel was in its (some have said) Golden Age at the same time (Dashiell Hammett’s fifth and final novel, The Thin Man, was published in 1934; Chandler and others would follow). Wolfe has given both of these genres “modern sensibilities” and made the marriage work seamlessly. One clever and easily overlooked merger (cavalierly tossed off as a mundane bit of business) is when we remind ourselves that the traditional PI gumshoe was hired by the day or week for a fairly steep price; with A Borrowed Man the library client checks out our author clone—who serves as our de facto PI—by the day or week for a hefty price, and to the same end. A fortuitous coincidence or a conscious eureka moment for the author?).

When reading these types of homages it is fun to theorize whether the author is referencing genre tropes in general, or a specific story or novel, or even a character (in the case of the detective genre). Your guess is as good as mine and only adds to the charm of this—on the surface at least—deceptively straightforward SF/detective novel.

The reading protocols with which one comes to the book will in large measure determine its success or failure on an individual basis. If read one way—as an obvious homage to the classic murder/detective novel of the 1930s & ’40s, replete with, and capturing the era’s social conventions (i.e. the relationship between men and women of that time, for but a single issue)—chances are it will be received favorably; if read, for example, from a contemporary feminist or other social issue viewpoint it might fail miserably, if such an issue-specific protocol were to be inappropriately applied.

Be all that as it may, there are two mysteries left for the reader to solve: on the science fiction side, what is the coded secret hidden within the pages of E. A. Smithe’s Murder on Mars that people are willing to kill for; and on the murder mystery side who killed X—whodunit?

Gene Wolfe must have had one helluva fun time writing A Borrowed Man. I know I had a helluva fun time reading it.

Below are non-specific representations of images found in The Borrowed Man. Those who have read the book will understand.

♣ ♣ ♣

Dave Truesdale has edited Tangent and now Tangent Online since 1993. It has been nominated for the Hugo Award five times, and the World Fantasy Award once. A former editor of the Bulletin of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America, he also served as a World Fantasy Award judge in 1998, and for several years wrote an original online column for The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. Now retired, he keeps close company with his SF/F library, the coffeepot, and old movie channels on TV. He lives in Kansas City, MO.

Gene Wolfe Photo courtesy of Beth Gwinn and is copyright © by Beth Gwinn. All rights reserved.

A Borrowed Man

A Borrowed Man