A critic, editor, and writer of astonishing range, Michael Moorcock is prolific, idiosyncratic, and outspoken—often too outspoken for many tastes, which has for nearly a half century had him fighting the censors. As he relates in his guest editorial in the July 2007 Interzone, he was arrested by Special Branch in the 1950s for bringing copies of William Burroughs‘ novels into Britain. A decade later, his magazine New Worlds raised a furor in the House of Commons by publishing Norman Spinrad‘s Bug Jack Barron. (You can find Moorcock’s own thoughts about the affair at The Edge.)

A critic, editor, and writer of astonishing range, Michael Moorcock is prolific, idiosyncratic, and outspoken—often too outspoken for many tastes, which has for nearly a half century had him fighting the censors. As he relates in his guest editorial in the July 2007 Interzone, he was arrested by Special Branch in the 1950s for bringing copies of William Burroughs‘ novels into Britain. A decade later, his magazine New Worlds raised a furor in the House of Commons by publishing Norman Spinrad‘s Bug Jack Barron. (You can find Moorcock’s own thoughts about the affair at The Edge.)

Indeed, it was not some government agency but Moorcock’s own publishers who saw to it that The Final Programme (the first of his Jerry Cornelius novels) and Byzantium Endures (the first of his Between the Wars cycle, also known as The Pyat Quartet, about which I wrote for the December 2006 issue of the New York Review of Science Fiction) both appeared in the United States in expurgated editions. Because Moorcock refused to allow Random House to do the same to the last two volumes of the Between the Wars saga (Jerusalem Commands and last year’s The Vengeance of Rome), it simply refused to release them in the U.S. at all, so readers can only get them online from other sources including, ironically, Random House’s British imprint, Jonathan Cape. (The buzz was that Random House refused to take on the last two books because of the protagonist’s copious anti-Semitic and anti-Islamic rhetoric, thus far preventing their release in the United States. Never mind that Random House has no qualms about publishing Ann Coulter’s anti-Arab and anti-Islamic diatribes, which routinely out-Pyat Pyat, and in doing so, have a far more inflammatory effect on public opinion than anything coming out of Pyat’s mouth.)

Moorcock has not pulled any punches in discussing the attempts by governments and the publishing houses to censor him, and the introduction to his collection, Legends From The End of Time, is a magnificent, thundering denunciation of the self-censorship that he saw as having "reached epidemic proportions in the U.S.," where "American publishers, who speak constantly and self-importantly of free speech, but are always glad to suppress it to protect a status quo favoring the privileged . . . encourage a level of self-censorship unheard of in most modern democracies."

Of course, the dialogue about self-censorship in America is itself self-censored, and what there is of one is dominated by self-styled right-wing "populists" with a narrow, partisan critique of political correctness which suffers through their linking it to that chimera, the "liberal elite." Lest the reader imagine Moorcock is one of these, he is perfectly clear in his introduction about what he means when he refers to the privileged and their status quo—an "imperial culture" in which "soldiers and tradesmen . . . run things . . . which always produces some version of Pinochet’s Chile. Or Serbia." (Incidentally, Moorcock wrote that introduction in 1998, three years before the September 11 attacks. They may have taken things to a whole new level, but it is a reminder that the problem goes deeper.)

Moorcock’s struggles have been particularly lengthy and well-documented, but make no mistake: he is not by any means the sole contemporary author to face such obstacles. The bestselling novelist Trevanian, whose Shibumi is perhaps the ultimate spy novel parody, and whose credits include the collection of comedic Arthurian tales, Rude Tales and Glorious that he published as Nicholas Seare, also spoke about this in a 1998 interview with Publisher’s Weekly, a very large part of which you can find quoted in an essay writer David J. Schow has posted on his website. Following his 1983 novel The Summer of Katya, he did not publish a book for fifteen years, not because he stopped writing, but because the publishers refused to take on what he was producing. In one case, a story of three young Parisian artists during the Revolution of 1848, the reason was that apart from being too "’hard’ . . . too many ‘big words,’ this last is a quote, God save American letters" the novel was "too political . . . All of Trevanian’s heroes have been anti-capitalist and anti-materialist, but America has evidently become more touchy about this cultural flaw."

Additionally, even if the problem is more advanced in the United States, it is by no means a purely American problem. Last year Moorcock’s longtime colleague, fellow New Wave legend Brian W. Aldiss, had a similar experience while seeking a publisher for his new novel, HARM, about a young Briton snatched up, interrogated, and tortured for months in the name of the War on Terror—all because of a few words in a novel his protagonist had written. While Aldiss’s depiction of Paul’s persecution is mild compared with what actually occurred in places like Abu Ghraib, he had great difficulty finding a British taker, and the book finally ended up at Duckworth, an old and established house to be sure, but one which almost never takes on speculative fiction.

Additionally, even if the problem is more advanced in the United States, it is by no means a purely American problem. Last year Moorcock’s longtime colleague, fellow New Wave legend Brian W. Aldiss, had a similar experience while seeking a publisher for his new novel, HARM, about a young Briton snatched up, interrogated, and tortured for months in the name of the War on Terror—all because of a few words in a novel his protagonist had written. While Aldiss’s depiction of Paul’s persecution is mild compared with what actually occurred in places like Abu Ghraib, he had great difficulty finding a British taker, and the book finally ended up at Duckworth, an old and established house to be sure, but one which almost never takes on speculative fiction.

As all this demonstrates the barriers are not airtight, but for anyone who cares about freedom of speech and expression, and the vitality of cultural life and political debate, very worrisome. Even if less complete this form of censorship is all the more insidious because the books are so quietly killed that no one knows censorship happened in the first place, making it easy for the thick and the willfully blind to deny that there is a problem. But there clearly is a problem, and what we know about is likely the tip of the iceberg. If a Moorcock, a Trevanian, an Aldiss can be shut out, what about those who do not have comparable prestige and sales on their side? What about those who are fighting their way through the slush piles, with nothing but form rejection letters to show for it—letters which, behind all the blandness, might be hiding the sad and sorry truth that the work in question was turned down for its politics? And what effect is this having on all those writers out there, those established and those just trying to break into the business who have caught on to this fact (and they do catch on), knowing what a tough business this is, how narrow the gateway and slender the chances for all but the very lucky? What are they not daring to say for fear of killing their careers before they even properly start?

Besides, where there is self-censorship, the other kind might not be too far behind. Those who paid attention when reading Ray Bradbury‘s classic, Fahrenheit 451, would remember that the "firemen" didn’t create the bookless world we see in that story; they just finished the job begun by the marketplace and the pressure groups. And as the ease with which the country tumbled into hysteria over Janet Jackson’s nipple; the efforts to rehabilitate Joseph McCarthy in some circles; the contempt for civil liberties among today’s high school students, as reported in recent polls; and other causes for worry too numerous to list here; there is no reason to think this country has become immune to such dangers.

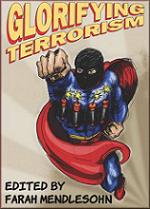

Indeed, where Aldiss is concerned, this may already be a factor. Britain’s Terrorism Act of 2006 explicitly forbids the publication of statements that "encourage" terrorism. Given the very broad definition of terrorism in the 2000 Terrorism Act, and of what might constitute its encouragement in this more recent bill, this basically grants the British government a free hand to criminalize political statements it does not like. Prejudices aside, that fact may have given Aldiss’s publishers pause, though it has also inspired a protest worth mentioning here. To demonstrate just how preposterous this law is, the Hugo-award winning editor, Farah Mendlesohn, assembled a collection of short stories which in no uncertain terms violate that law, titled Glorifying Terrorism, in case "the Demon Headmaster" and company miss the point. This collection, which contains stories by major British authors including Ken MacLeod, Gwyneth Jones, and Ian Watson, is published by Rackstraw Press, created expressly for the purpose of getting this book out there.

Indeed, where Aldiss is concerned, this may already be a factor. Britain’s Terrorism Act of 2006 explicitly forbids the publication of statements that "encourage" terrorism. Given the very broad definition of terrorism in the 2000 Terrorism Act, and of what might constitute its encouragement in this more recent bill, this basically grants the British government a free hand to criminalize political statements it does not like. Prejudices aside, that fact may have given Aldiss’s publishers pause, though it has also inspired a protest worth mentioning here. To demonstrate just how preposterous this law is, the Hugo-award winning editor, Farah Mendlesohn, assembled a collection of short stories which in no uncertain terms violate that law, titled Glorifying Terrorism, in case "the Demon Headmaster" and company miss the point. This collection, which contains stories by major British authors including Ken MacLeod, Gwyneth Jones, and Ian Watson, is published by Rackstraw Press, created expressly for the purpose of getting this book out there.

The ultimate consequences of Britain’s legislation remain to be seen, but the protest mentioned here is a reminder of an important part of science fiction’s history. Writers in this medium may not enjoy the ghetto to which they have been relegated by literary snobs—and Moorcock certainly has a lot to say about that issue as well—but it has had its uses, not the least of them that its authors can say things the "Litfic" crowd will not. If the genre loses that, we will all be the poorer for it.