This July marks the hundredth anniversary of Robert Anson Heinlein’s birth, an event commemorated by The Heinlein Centennial, Inc., an independent group of Heinlein admirers, at the Robert A. Heinlein Centennial in Kansas City, Missouri. If all goes according to plan, a separate group, The Heinlein Society, plans to publish The Heinlein Centennial Reader later this year. (The winners of The Heinlein Centennial’s story contest may be found at their website. The Heinlein Society has announced their short story contest, and they promise details will be available soon.)

This July marks the hundredth anniversary of Robert Anson Heinlein’s birth, an event commemorated by The Heinlein Centennial, Inc., an independent group of Heinlein admirers, at the Robert A. Heinlein Centennial in Kansas City, Missouri. If all goes according to plan, a separate group, The Heinlein Society, plans to publish The Heinlein Centennial Reader later this year. (The winners of The Heinlein Centennial’s story contest may be found at their website. The Heinlein Society has announced their short story contest, and they promise details will be available soon.)In the process he helped to both form the clichés about the genre (its conservative leanings, its engineering mentality, our Jetsonian future), and refute them. Rightly credited with doing much to bring the social, political, and sexual into American science fiction (which, in all fairness, lagged behind Brits like Huxley and Orwell and Stapledon in this regard), he also helped bring the genre its first exposure in mainstream publications like The Saturday Evening Post and mainstream bestseller lists. And as H. Bruce Franklin observes in his study, Robert A. Heinlein: America as Science Fiction, he was also the first to gain even token acceptance "in high-class literary neighborhoods."

Additionally, while the film versions of Heinlein’s own novels, like those of a great many other classic science fiction writers, have not been notably successful (though as I write this, the second sequel to 1997’s Starship Troopers is reportedly going into production), and a complete account of Heinlein’s Hollywood projects (which you can find J. Daniel and James Gifford‘s Robert A. Heinlein: A Reader’s Companion) can read like a study in frustration, Heinlein may even have had a greater impact on cinematic science fiction than is generally appreciated. 1950’s Destination Moon, in which he was personally involved, is in Dwayne A. Day‘s assessment, "to science fiction film what D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation was to filmmaking in general."

Additionally, while the film versions of Heinlein’s own novels, like those of a great many other classic science fiction writers, have not been notably successful (though as I write this, the second sequel to 1997’s Starship Troopers is reportedly going into production), and a complete account of Heinlein’s Hollywood projects (which you can find J. Daniel and James Gifford‘s Robert A. Heinlein: A Reader’s Companion) can read like a study in frustration, Heinlein may even have had a greater impact on cinematic science fiction than is generally appreciated. 1950’s Destination Moon, in which he was personally involved, is in Dwayne A. Day‘s assessment, "to science fiction film what D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation was to filmmaking in general."

As the more astute scholars of Heinlein have recognized, the sensibility he brought to all of it escapes easy labeling, but the subtitle of Franklin’s study, America as Science Fiction, has always struck me as a fitting description of his oeuvre. Like the country that his work so often commented on and reflected, his sensibilities defied easy categorization. He could be self-deprecating and magisterial, earnest and ironic, ebulliently optimistic and hopelessly bleak; ruggedly individualistic to the point of Social Darwinism and as Philip K. Dick put it in his wonderful essay, "Now Wait For this Year," "God bless him—one of the few true gentlemen in this world"; a hard-boiled pragmatist and an exceedingly demanding moralist, often in the same breath. A denouncer of anti-intellectualism, he would himself be open to criticism on that score, Brian Aldiss in Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction (himself an admirer of much of what Heinlein had written who goes so far as to say "in the early forties . . . he could do no wrong") arguing that Heinlein’s work tends to reject the subtlety and complexity of the world and say instead "Don’t listen to all these experts with their jargons and explanations . . . it’s as simple as this—and we are given a cartoon, an old folk-saying."

Quick to describe himself as an entertainer, often reveling in the more mercenary side of the writing business (as Jubal Harshaw did), Heinlein also wrote novels of ideas, and for at least a few, could be irksomely didactic when he opted to step into the role of educator on important issues of the day. While his record there was mixed, he swiftly recognized the awful implications of nuclear weapons after Hiroshima, about which he wrote at length. He may also have done more than any other American of those years right before the space age to popularize the idea of space travel, a role that Dwayne Day has recently devoted a series of articles to documenting at the Space Review.

Naturally, this propensity for contradiction carried over to his politics, about which he was highly outspoken. While Heinlein is generally and not improperly thought of as a conservative, in the impoverished terminology of our polarized times he was neither Red nor Blue (even geographically, having been born in Butler, Missouri, right in the South’s Bible Belt, then going on to spend most of his life in California). His views on race and sex were progressive, particularly for his day (though he would often be accused of an underlying racism and sexism, as with Farnham’s Freehold), and his views on religion put him in the same corner as Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris (though he would toy with magic and mysticism as in "Waldo," and with religious themes in works like Job: A Comedy of Justice). At the same time, however, he was a staunch believer in the free market, given to popularizing Milton Friedman‘s aphorisms (though a socialist during the Depression) and a foreign policy hawk (who supported the war in Vietnam while being against the draft—and expressing less than enchantment with the enterprise in Glory Road). Starship Troopers would get him accused of being a fascist, while the very next book he published, Stranger in a Strange Land, would be hailed as a counterculture classic—and both won the Hugo Award for their years.

A libertarian who defended Joseph McCarthy, and at different times in his life active in the political campaigns of both Upton Sinclair and Barry Goldwater, perhaps the one point on which he seemed truly unwavering was his great admiration for the military. A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy (where he famously spoke before the graduating class in 1973, and where there is now an endowed Robert A. Heinlein Chair in Aerospace Engineering), he served for seven years as a naval officer before his career was cut short by tuberculosis, an experience which was clearly one of the greatest influences on him. In Time Enough for Love, though, he not only joked about that too (in "The Tale of the Man Who Was Too Lazy To Fail"), but pictured a future without war as humanity spreads out across the universe in every direction.

In the end there was not just "one Heinlein," but many, sometimes one or more in each novel (there he is in Lazarus Long, and there in the Old Man, and here in old Jubal), though readers usually differentiate them by period. The "early" Heinlein of the 1940s and 1950s, during which time he wrote classics like Methuselah’s Children, The Puppet Masters, and The Door Into Summer, often seems to get the most praise. Still, while they elicit as much harsh criticism as glowing adulation, it is probably the works of Heinlein’s middle years, like Starship Troopers and Stranger, that he is best remembered for today. (I would go so far as to agree with Robert Gorsch that this was Heinlein’s true "golden age.")

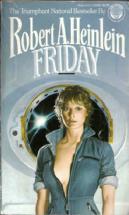

There is a tendency to view the books that followed in the 1970s and 1980s less favorably, with even devoted fans often denigrating novels like I Will Fear No Evil and The Number of the Beast. The harsher will say that they are bloated, self-indulgent, and lacking in the qualities that made the earlier stuff so compelling (which did not prevent them from enjoying vast commercial success). Still, I have long felt that some of that output too deserves a look, particularly his 1982 novel, Friday. Rarely discussed (apart from my own Summer 2006 Foundation article, there is only one other piece about it listed in the Modern Language Association database), it is not just a brisk read reminiscent of the good old days, but despite its imperfections, intriguing as a case of Heinlein-meets-postmodernity. Friday thrusts his titular heroine into a cyberpunk world, complete with casual transhumanism and a Pynchonian touch in its conception of the Shipstone Corporation. (In fact, the novel caught my interest as not just a science fiction reader or even a literary critic, but as a novelist; Friday was also one of the sources of inspiration for my—alas, still unpublished—Tales From the Singularity.)

There is a tendency to view the books that followed in the 1970s and 1980s less favorably, with even devoted fans often denigrating novels like I Will Fear No Evil and The Number of the Beast. The harsher will say that they are bloated, self-indulgent, and lacking in the qualities that made the earlier stuff so compelling (which did not prevent them from enjoying vast commercial success). Still, I have long felt that some of that output too deserves a look, particularly his 1982 novel, Friday. Rarely discussed (apart from my own Summer 2006 Foundation article, there is only one other piece about it listed in the Modern Language Association database), it is not just a brisk read reminiscent of the good old days, but despite its imperfections, intriguing as a case of Heinlein-meets-postmodernity. Friday thrusts his titular heroine into a cyberpunk world, complete with casual transhumanism and a Pynchonian touch in its conception of the Shipstone Corporation. (In fact, the novel caught my interest as not just a science fiction reader or even a literary critic, but as a novelist; Friday was also one of the sources of inspiration for my—alas, still unpublished—Tales From the Singularity.)

Nonetheless, the mixed response to his later writing did not seriously damage his reputation. Not only did he remain an important influence on later authors, from the cyberpunks of the 1980s (as Bruce Sterling acknowledged in the preface to Mirrorshades), to the military science fiction writers today centered on Baen Books, but the books Heinlein wrote himself have continued to enjoy a wide readership of their own. Those who imitated rather than took inspiration would often do it all over again bigger, louder, flashier, but never with the same freshness and depth, which is perhaps what keeps him from being just another "important" writer without a living, breathing fan base that reads him not for the sake of school or work, but because they genuinely want to. (Just two hours prior to my writing these words, I was on the train when I noticed that the commuter just across the aisle from me was reading a copy of Starman Jones, which naturally started a conversation. Sure enough, he was a fan.)

There is, of course, no way to really guess how long that will go on being the case, fashions being a fickle thing (and yes, even a genuine classic is subject to these), but I wouldn’t be terribly surprised if Heinlein’s fans reconvened in Kansas City to mark a Heinlein Bicentennial in 2107. And maybe, just maybe, there’ll be a flying car in every garage then.