Doctor, Will the Patient Survive?

By Sheila Finch

How healthy is science fiction? As a longtime reader of the genre, I seem increasingly to have the experience of finishing a story in an SF magazine and wondering what on Earth it was doing there. The fantasy stories seem to thrive (although a lot of them begin to sound alike, a side effect of the genre’s popularity, I suppose), but I think something more disturbing has been occurring in science fiction.

Gary Wolfe once referred to this trend as “creeping mainstreamism”: a trend that produces stories that embrace all the aspects of literary fiction, style, character development, and so on, but lose the element of speculativeness that marks science fiction. What we’re all too likely to find in the magazines these days (with Analog a notable exception) is the story that might just as well have appeared in The New Yorker or any of the literary journals. What’s happened here?

If we imagine genre fiction—westerns, romance, SF, and so on—as an archipelago in the literary sea, then on our island of science fiction we find the mountains are healthy but the coastline is eroding rapidly. . . . What worries me is that especially in short fiction it’s getting harder and harder to find the middle-ground story of the kind James Blish and Clifford D. Simak used to write, or A. E. van Vogt and James Tiptree, Jr., and Judith Merril, the story that doesn’t require the reader’s familiarity with advanced scientific concepts or terminology, but which turns on a genuine scientific point. Such stories satisfy the reader’s hunger for experience of life and times different from her own, events that compel page turning, and ideas that linger in the mind long after the story is done. “Ask the next question,” Theodore Sturgeon advised. Unfortunately, I think too many stories today don’t begin to answer the first.

The rule I learned said, “If you can take the scientific gadgetry out and still have a story, then take it out and write mainstream.” But the stories I’m concerned about don’t even pay much lip service to science or technology; they simply have no speculative core. (I’m not talking about alternate history stories here, an interesting use of the traditional SF story-generating question, what if….) Often, the only element of the tale that makes a nod toward a territory not mapped out by the mainstream is a vague reference to something along the lines of the telepathic abilities of a character—they hear voices or are given sudden flashes of inisght into people or events. Yet it often seems the mere introduction to such ideas has satisfied the author’s sense of obligation to the readers, the implications and consequences of these abilities mostly go unexplored, and I’m left daydreaming about what Alfred Bester or Sturgeon would have done with such stories. What we have instead, to change our metaphors, is prose by authors who’ve lost their nerve for the high-wire act of science fiction. I suspect there are several reasons for the rise of this type of story.

The first cause is rather obviously the rising number of nonscientist writers. We’re witnessing the growing community of writers who are humanities and liberal arts majors, bringing with them a greater familiarity with the classics of the literary canon and the pronouncements of literary critics rather than the papers in Science. This is a trend that began decades ago with the New Wave. I’m not denying the good things such writers have done for the field: deeper attention to characterization, a finer sensitivity to language and style, an opening up of the traditional SF plot and theme to ambiguity and complexity. When such refinements are brought to bear on an extrapolation of scientific ideas, the result is the best kind of literature in or out of the genre.

But literary stories often promote these stylistic values over the exploration of idea or concept, with the result that too often the stories read as if the author were writing with her graduate thesis professor frowning over her shoulder (a rather grim individual for whom scientific advance began and ended with Newton). The science in these stories is either unexceptional, or nonexistent.

A related cause of the problem is that in a fair world many of these writers would find their true homes in mainstream magazines, which would pay them in something other than copies and distribute their work to the appropriate audience. Alas, such paying markets for short story writers have shrunk disastrously in the last few years, leaving the genre magazines as the only real alternative for writers who also like to eat once in a while. Since, as we’ve noted, the quality in these stories tends to be high, I’m not surprised editors are attracted to them. But they leave many SF readers feeling hungry.

I believe another culprit is the current admiration for South American magic realism. Fiction from south of the border has become fashionable, and as a result we’re seeing too much emulation of Gabriel García Márquez and too much adulation of Isabel Allende. In magic realism, we’re drawn into settings (the Revolution, colonial days) where complex characters with believable goals and problems are explored realistically, and whimsical or supernatural events (floating above the ground, green hair) are described casually. Yet the fantastic elements aren’t the whole cloth of these stories; they’re an enrichment of the plot, a subtle embroidery of theme.

But a lot of short science fiction these days is built around a thin thread of a fantastic detail that is the whole story. Nothing other than this slender magical or genteelly bizarre element is offered to the reader. When George Scithers was editor of Amazing, he cautioned would-be authors against committing the “tomato surprise” story that revolved around one vital point, usually withheld until the end. I’m seeing a lot of surprising tomatoes these days, stories where once such a fantastic or magical point is removed, the story not only isn’t science fiction, it isn’t even much of a story.

Luckily for us, there are still short story writers in the genre like Jack McDevitt, Martha Soukup, Maureen F. McHugh, Mike Resnick, Joe Haldeman, Bradley Denton, Ray Aldridge, and many others, who can tell a gripping SF tale, peopled with complex, well-drawn characters, and pull it off with elegance and subtlety. Their stories are the ones we stay up late to finish reading, then wake in the night to think about again. They are the vitamin pills worth looking for in a gaudy jar full of word candy.

If the genre is going to survive and attract new readers, these are the writers who’ll make it happen. Some of them, I’m happy to say, are represented in this volume.

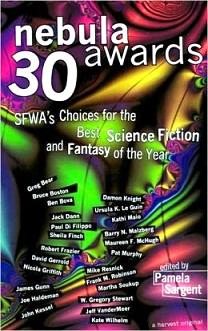

—”Doctor, Will the Patient Survive?” reprinted with permission from Nebula Awards 30, ed. Pamela Sargent (Harcourt, Brace, 1996)

[Editor’s note: This essay was published eighteen years ago, in 1996. I asked the author if she felt her observations and insights remained valid or if times had perhaps changed, the situation perhaps improving, or correcting itself. Her answer came by way of granting permission to reprint her essay verbatim, for which I once again extend my appreciation and thanks.]