Collecting Fantasy Art #9

Darrell and Sam–

Two Famous Collectors

By Robert Weinberg

Copyright © 2011 by Robert Weinberg

~One~

The world is filled with odd coincidences. They fill our lives but most of us refuse to admit that they exist, or more to the point, that they often happen to us. When we see such coincidences in movies, on TV, or read about them in books, we shake our head in annoyance and mutter something like “never happens” or “outrageous.” We are much too practical to believe in such silliness. But, like it or not, the world functions in ways that cannot be explained by simple logic. All of which serves as a proper introduction to the two art deals that tie together this chapter with the previous one. The first deal connects in a very odd manner the Church of Scientology, my employers for three days in the last chapter, with famous SF collector, the Rev. Darrell C. Richardson. The second deal connects in even an odder fashion Dr. Christine Haycock, the widow of famous SF historian, Sam Moskowitz, with the Church. Proving that truth sometimes can be stranger than fiction.

One of the legendary science fiction and fantasy book, magazine, and art collectors of the 20th century was the Rev. Darrell C. Richardson. A Southern Baptist Preacher, Darrell owned one of the finest Edgar Rice Burroughs book collections in the world. He also owned thousands upon thousands of science fiction hardcover books stretching back into the 19th century, as well as a complete run of all the science fiction magazines. Along with the SF publications, he owned thousands of other pulp magazines, including a huge run of Argosy issues, the prize of which was the 1912 magazine with the novel, Tarzan of the Apes, complete in one issue. That pulp was considered the most valuable science fiction magazine ever published.

One of the legendary science fiction and fantasy book, magazine, and art collectors of the 20th century was the Rev. Darrell C. Richardson. A Southern Baptist Preacher, Darrell owned one of the finest Edgar Rice Burroughs book collections in the world. He also owned thousands upon thousands of science fiction hardcover books stretching back into the 19th century, as well as a complete run of all the science fiction magazines. Along with the SF publications, he owned thousands of other pulp magazines, including a huge run of Argosy issues, the prize of which was the 1912 magazine with the novel, Tarzan of the Apes, complete in one issue. That pulp was considered the most valuable science fiction magazine ever published.

Darrell also owned a fabulous art collection. One of the highlights of his collection were several paintings by J. Allen St. John, the famous artist who had illustrated many of the Tarzan books. The Rev. Richardson owned the cover painting for Tarzan Lord of the Jungle, a famous illustration of the jungle lord fighting a gigantic snake. The Reverend also owned several other St. John paintings that had appeared as original illustrations inside ERB hardcover books. Plus, he was the owner of three St. John cover paintings done for the Ziff Davis magazines, Amazing Stories and Fantastic Adventures. Darrell had bought the art directly from St. John whom he had met at his Chicago studio in 1950.

As a Baptist minister, Darrell was no fan of the Church of Scientology and as best as I was able to determine, he refused to deal with them in any way. Still, the Rev. Richardson and the Scientologists were linked by a piece of original artwork. With me, strangely enough, serving as the connection between the preacher and the Order.

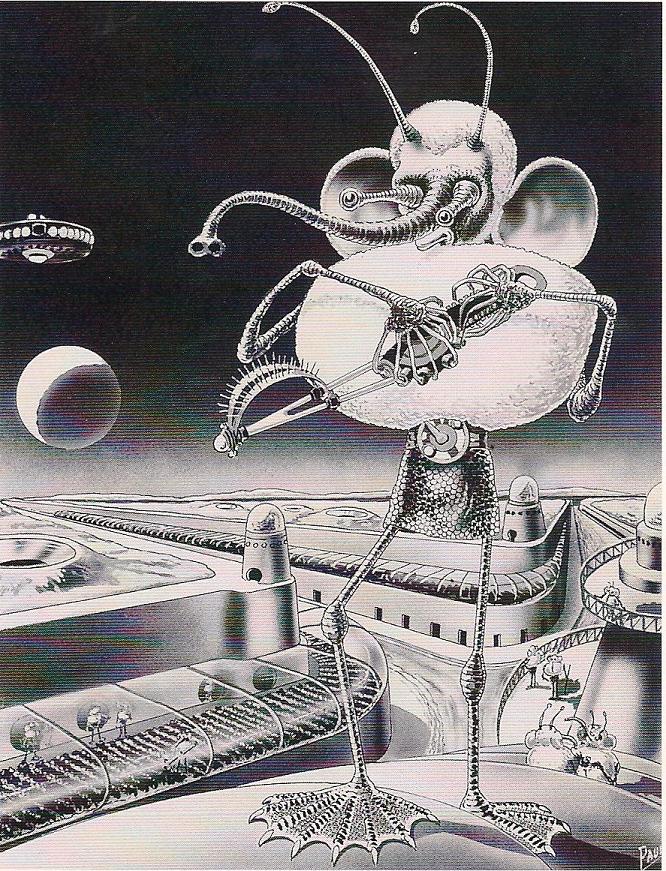

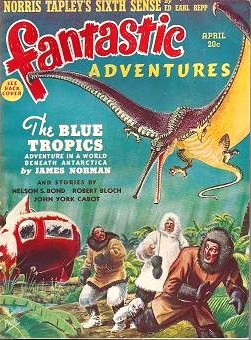

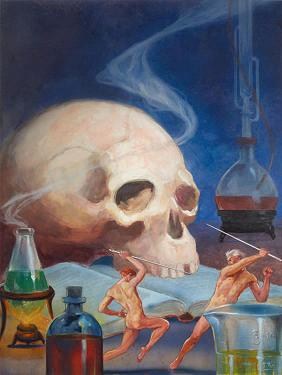

The history of that connection began at PULPcon #6 held in Akron, Ohio. It was a good show, centered around a dealer’s room filled with old pulp magazines for sale. Needless to say, there were a number of attractive science fiction and pulp magazine covers on display at various locations in the room. Most were for sale, but some were there just for show. Among the latter were several paintings at the table of the Rev. Darrell Richardson. The best piece was a Frank R. Paul painting from Fantastic Adventures from 1939 that illustrated a story titled “The Blue Tropics.” Darrell’s other treasure was a stunning St. John cover for Amazing Stories from 1943 featuring two naked men only a few inches tall, fighting on a desktop. Interesting but not nearly as nice was a Rod Ruth cover for Amazing from 1940. Much nicer, though not nearly as old, was a Norman Saunders painting from May 1951 for the short-lived digest magazine, Marvel Science Stories.

The history of that connection began at PULPcon #6 held in Akron, Ohio. It was a good show, centered around a dealer’s room filled with old pulp magazines for sale. Needless to say, there were a number of attractive science fiction and pulp magazine covers on display at various locations in the room. Most were for sale, but some were there just for show. Among the latter were several paintings at the table of the Rev. Darrell Richardson. The best piece was a Frank R. Paul painting from Fantastic Adventures from 1939 that illustrated a story titled “The Blue Tropics.” Darrell’s other treasure was a stunning St. John cover for Amazing Stories from 1943 featuring two naked men only a few inches tall, fighting on a desktop. Interesting but not nearly as nice was a Rod Ruth cover for Amazing from 1940. Much nicer, though not nearly as old, was a Norman Saunders painting from May 1951 for the short-lived digest magazine, Marvel Science Stories.

Darrell had a bunch of lost race novels for sale at his table. Most were from the 1920s and before and were at best in fair condition. No one was particularly interested in such books when there were thousands upon thousands of pulps for sale. Thus, most of the weekend the Reverend sat behind his book display and watched collectors walk past his table without stopping to look at his wares. When they did pause, it was only to examine his paintings. By the time Sunday rolled around, Darrell was ready to deal. He had hoped to earn enough money from sales to pay for his trip to Akron, but his lost race novels had sunk like a stone. It was time to unload his big guns. He decided to put up two of his paintings for sale. The ones he selected were the Rod Ruth Amazing cover and the Norman Saunders Marvel Science Stories illo.

Darrell had a bunch of lost race novels for sale at his table. Most were from the 1920s and before and were at best in fair condition. No one was particularly interested in such books when there were thousands upon thousands of pulps for sale. Thus, most of the weekend the Reverend sat behind his book display and watched collectors walk past his table without stopping to look at his wares. When they did pause, it was only to examine his paintings. By the time Sunday rolled around, Darrell was ready to deal. He had hoped to earn enough money from sales to pay for his trip to Akron, but his lost race novels had sunk like a stone. It was time to unload his big guns. He decided to put up two of his paintings for sale. The ones he selected were the Rod Ruth Amazing cover and the Norman Saunders Marvel Science Stories illo.

Now, back in the 1970s and early 1980s, there were only a handful of fans and collectors interested in buying original science fiction art from the 1930s and 1940s. In general, science fiction fans were only interested in art from the 1950s on – pieces by artists like Richard Powers and Kelly Freas and Ed Emsh and Ed Valigursky. Art like I had been selling for several years by that time from Ace paperbacks. The audience for art by Rod Ruth and Norman Saunders was very limited. At PULPcon 6, it consisted of perhaps four or five fans total. I was one of them, as was an old friend, Walker Martin. Walker had been collecting pulp art for years and he was always interested in originals from those magazines. He actually preferred the Rod Ruth cover because it had been used as a pulp cover, whereas the Saunders had appeared as the cover for a digest-sized magazine.

Needless to say, Walker was the high bidder on the Rod Ruth painting, which sold for less than $100. I had to pay more for the Norman Saunders Marvel cover piece, which I thought was a much nicer painting. It cost me nearly $200. Thus, Darrell earned enough money to pay his expenses for the weekend and Walker and I each ended up with an original SF painting. But the story doesn’t end there.

I bought the May 1951 Marvel Science Stories cover (at right) at PULPcon 6 in 1978. At the time, Phyllis and I were living in a small home in Chicago. In 1980, after my son Matt was born, we decided that we needed a bigger home, so we bought a house in the Chicago suburbs. While we had enough money for the down payment, we needed some extra cash to pay for a new refrigerator. So, much as I hated doing it, I decided to sell the Saunders painting I had bought from the Rev. Richardson a few years before. I put the piece up for sale in my monthly book catalog, priced at $600. It sold almost immediately. It was bought by John McLaughlin, a wealthy California collector who ran a rare bookstore, mostly for his own amusement, known as “The Book Sail.” McLaughlin was notorious for paying extraordinary sums for Margaret Brundage Weird Tales cover paintings and owning a huge home with a full-grown tree located in the center of the mansion on an open-air patio.

I bought the May 1951 Marvel Science Stories cover (at right) at PULPcon 6 in 1978. At the time, Phyllis and I were living in a small home in Chicago. In 1980, after my son Matt was born, we decided that we needed a bigger home, so we bought a house in the Chicago suburbs. While we had enough money for the down payment, we needed some extra cash to pay for a new refrigerator. So, much as I hated doing it, I decided to sell the Saunders painting I had bought from the Rev. Richardson a few years before. I put the piece up for sale in my monthly book catalog, priced at $600. It sold almost immediately. It was bought by John McLaughlin, a wealthy California collector who ran a rare bookstore, mostly for his own amusement, known as “The Book Sail.” McLaughlin was notorious for paying extraordinary sums for Margaret Brundage Weird Tales cover paintings and owning a huge home with a full-grown tree located in the center of the mansion on an open-air patio.

Now, as I’ve mentioned before, the science fiction art field is small and the players involved in buying and selling art rarely change. They merely get older. As was the case with the owner of the Norman Saunders painting. John hung onto the piece, though as was his custom, he listed it from time to time for sale from the Book Sail at ten times what he paid for it. He liked putting his art treasures up for sale at ridiculous prices, feeling that by doing so he was establishing a new, higher value for the art. He therefore would argue that the Saunders painting was worth $6,000 because it was listed for sale in a bookseller catalog for that price. That he owned the painting and published the catalog with that listing was conveniently never mentioned. McLaughlin was rich, having inherited a fortune from his parents, and one of the benefits of having lots of money was that no one bothered arguing with you. Nor did anyone (as far as I could determine at the time) ever buy anything from your bookstore. Not that McLaughlin cared. His store existed mainly as a place for him to display some of his many treasures.

Unfortunately, when I was hired by the Church of Scientology (as described in last month’s article), one of the cover paintings they really wanted for their L. Ron Hubbard exhibit was the cover for the May 1951 issue of Marvel Science Stories. It seemed that that particular issue of the magazine featured a debate between Lester del Rey and L. Ron Hubbard on Dianetics, the scientific study that Hubbard started that evolved into Scientology. The Church really wanted that cover piece so I reluctantly told them that it was owned by John McLaughlin. Fortunately for me, since McLaughlin lived in California, where the headquarters of the Church of Scientology was located, Tom Vm., the head of their research department decided to deal with McLaughlin direct. I thought this was a wonderful idea. I knew from previous experience that dealing with the owner of the Book Sail was the quickest way to get an intense headache.

Now, let’s tie everything neatly together. Darrell Richardson bought the cover for the May 1951 issue of Marvel Science Stories at an early World SF Convention. He kept it in his collection for years and years before bringing it to the 6th PULPcon in 1978. I bought the original painting at that show. Two years later I sold the painting to John McLaughlin. Nearly twenty years later, the Church of Scientology decided to buy the original painting from McLaughlin. Tying together in a very strange manner, over the course of several decades, the Rev. Darrell Richardson and the Church of Scientology. Except for the fact that John McLaughlin got a certain perverse pleasure from owning original pieces of art that other people wanted. In other words, despite the Church making several spectacular offers to buy the Norman Saunders painting, McLaughlin refused to sell it to them, no matter what they offered. The last I heard of it in mid-1999, the Church was still trying to buy the art. And McLaughlin was steadfastly refusing to sell.

But wait! The story isn’t over. John McLaughlin died several years ago. Much of his collection was put up for sale at auction, including the Norman Saunders original. It sold on August 19, 2010 for $50,790. I don’t know who bought it, though I have my suspicions. The price it brought was another lesson to me that I needed to ask higher prices on the originals I offered for sale.

Dial back to 1999. The Church of Scientology was engaged in a no-win battle with John McLaughlin trying to get the Norman Saunders from him. I was not involved in the fight. However, what their disagreement did do was remind me of PULPcon 6 and the artwork that Darrell had exhibited at his table. A few years back, in the early 1990s, a comic book art dealer named Russ Cochran had bought several of the St. John paintings owned by the Rev. Richardson. The ones sold included all of the originals for the ERB hardcover books as well as the original for “It’s a Small World.” Russ paid huge prices for the St. John pieces. However, he didn’t buy the Frank R. Paul painting, “The Blue Tropics,” from Darrell. Nor had he bought any of the other science fiction and fantasy paintings that Richardson owned. All of which started me thinking that maybe it was time to see if Darrell might be willing to sell something else.

The Rev. Richardson had stopped attending PULPcon in the late 1990s. His health had grown progressively worse over the years. A big, powerfully built man, he had suffered a major stroke and lost a lot of weight and was a mere shell of his former self. Plus, he had just about lost his hearing.

According to talk among collectors, Darrell had moved into a condo with one of his two sons and was living a quiet life as a retired collector. Still, as far as anyone could tell me, he still owned his entire collection of rare books and pulp magazines, as well as most of his art.

Proving beyond a shadow of a doubt that great minds think in similar ways, my close friend Steve K. called me a few days after I started thinking about Darrell. Never one to hesitate when he had a good idea, Steve wanted to talk to me about a great one. Why didn’t we contact the Rev. Darrell C. Richardson and see if we could make a deal with him to buy his collection much as we had done with Sam Peeples? We could buy all of Darrell’s art for ourselves and sell his books and magazines at a huge profit thus covering the cost of the artwork. Thus, with just a reasonable amount of money, and a fair amount of effort, we could add some terrific art to both our collections.

It was a good plan for the circumstances. I knew Darrell would want to be paid upfront for his artwork and Steve had plenty of cash. On the other hand, Steve was not capable of selling thousands of rare books and science fiction magazines, and I was. Together we made a good team. We had done quite well selling the Peeples collection, and we felt confident we could do equally as well with the Reverend’s collection. So Steve called Darrell’s son and we made an appointment to see him and his father the next week.

~Two~

Steve and I arrived in Memphis, Tennessee, in mid-May 1999. We had called ahead and spoken with Don, Darrell’s younger son, about coming. Don had asked his father if it was okay, and Darrell had given his consent. He also knew that we were coming to make an offer on his huge collection. According to Don, Darrell thought that this was a great idea, Don did warn us of one problem. Darrell’s hearing had gotten a lot worse. Even with hearing aids in both ears, he could hardly hear. When talking to the Rev. Richardson, we would have to shout – and shout from in front of Darrell. If we tried to communicate with him by speaking from behind him, he’d never hear a word. He had to see our mouths moving so he knew to concentrate on what we were saying.

I had never been in Memphis, so the first thing we did when the four of us got together was go on a sightseeing trip of the city. Which mostly meant that we stopped at several locations important to the Elvis Presley legend, including Graceland and Katz’ drugstore, where we had an ice cream soda. Afterwards, Don drove us to his condo, located in an attractive apartment building on a tree-lined boulevard a few minutes from the downtown section of the city. Darrell, we were told, had the condo directly across the hall from Don.

Don’s condo was a collector’s dream. The apartment was lined with bookcases, all of which were filled with rare and collectible books from his father’s collection. There was a huge display of late 19th century and early 20th century British boy’s adventure hardcover books, hundreds of them in raised and decorated bindings. According to Darrell, his set was the best in the world. There was a huge Edgar Rice Burroughs collection, consisting of many first editions along with most of the early reprint editions. There were shelves and shelves of early science fiction and fantasy novels, along with many novels reprinted from the adventure pulp magazines of rht 1920s and 1930s. It was in Don’s apartment that I finally saw a copy of Robert E. Howard’s first book, the legendary A Gent from Bear Creek, published in England in 1937. The book was so rare that only a half-dozen copies were rumored to exist, the rest having been destroyed during World War II. And there was more!

There were bookcases stretching from the floor to the high ceiling, filled with rare and obscure lost race novels, mostly from England and the turn of the century. There were cover paintings on the walls in that room, original covers from Famous Fantastic Mysteries painted by Lawrence Sterne Stevens, illustrating famous lost race stories by H. Rider Haggard. Plus, in the furthest bedroom from the living room was an entire wall covered with bookshelves from the wall to the ceiling. The cases were filled with old pulp magazines, thousands and thousands of them, from the early days of the 20th century to the 1950s when the pulps died. There was a huge run of Argosy, a collection of New Story, issues of The Mysterious Wu Fang, and Dr. Yen Sin. Copies of The Shadow stood alongside of issues of Doc Savage, held in place by runs of The Skipper and The Whisperer. It was an incredible display, one that took your breath away. Everywhere we looked in that condo were collectibles.

Darrell’s condo had more books, but they were not as rare or desirable as the ones in Don’s place. That was because Darrell originally lived in a house a dozen blocks away by himself. After being robbed several times, Darrell had decided to move, but no condo was available in Don’s building. Darrell instead had moved all his valuable material into Don’s place and then moved in himself. He lived with his son for many months, waiting for another condo to open up. Meaning that along with the books and pulps in Don’s condo and Darrell’s condo, there was also a houseful of books and magazines to explore as well. Not to mention all of the art that Darrell owned, most of which was no longer hanging up but was stacked in several large piles in one of the guest bedrooms.

We spent all of Friday traveling around Memphis, then examining the books and pulps in Don’s apartment for the rest of the day and evening. Saturday we decided would be used to examine the material that Darrell had at his house, then we would go over the art and see if we could make a deal for that. Which left Sunday for us to make a deal on the rest of the collection. The Rev. Richardson might be old, but he was no fool. His nickname among Edgar Rice Burroughs collectors was “The Old Tiger.” He seemed ready to fight like a tiger to insure he got the best price possible for his collection.

The next day Steve and I got up early at our hotel room and drove over to Don’s condo. Don and Darrell were already waiting for us. Together, the four of us drove over to the old house Darrell had once lived in for many years in Memphis.

Needless to say, this place was also filled with books and pulps from floor to ceiling. Even the garage unattached to the house was filled with pulp magazines. Unfortunately, the house was not air conditioned and it was extremely hot that day.

A near complete set of Weird Tales pulp magazine was the best find on the main floor of Darrell’s house. There were stacks and stacks of old books as well, but they were old mysteries by authors we had never heard of and of little value. Steve, shouting, asked Darrell how he had accumulated so many old books. Shouting back at us, Darrell explained how he had assembled much of his book collection.

After World War II, Darrell had traveled around the USA as a Baptist preacher, making appearances in churches all over the countryside. Knowing his speaking schedule in advance, he ran classified ads in the town newspapers where he was scheduled to make an appearance, stating that he was coming to town and was buying old mystery and science fiction books and magazines. In town after town, he was overwhelmed by people with old paper for sale at dirt cheap prices. All in all, he had doubled the size of his collection in a few months, and a scoop a little later, doubled the size again.

Darrell then insisted we walk up a shaky flight of stairs to the attic that covered the entire house. On the floor of the rear part of the attic were thousands and thousands of books in small stacks on the floor and on low bookcases. In the middle of the attic were tall bookcases packed with more books. In the front of the attic, where the temperature had to have been over a hundred degrees, were runs of most of the science fiction pulps, including Amazing, Astounding, and the Wonder pulps.

Sweating profusely, I tried looking at the hardcover books as quickly as possible. Most of the books were cheap hardcover reprints of old science fiction and fantasy novels. There were a few good books, including a bunch of E.E. Smith Lensman adventures inscribed to Darrell, by the author, but for every book like those, there were ten books that were not worth more than a dollar. There were some interesting British hardcover books, including a pre-World War II set of the famous Jack Mann “G’s” mystery/fantasy novels, but they were surrounded by a hundred less than exciting hardcover volumes. No matter what we paid for this selection of volumes, it would be too much.

Bedraggled and thirsty, we returned to Don’s condo where we gulped down several bottles each of soda pop. Now, after having seen all the books and magazines in Darrell’s collection, we were expected to bargain for his pieces of original art. Most of which we had not seen up to this moment.

Don pulled out the art from the spare bedroom and spread it across the living room. He leaned the pieces against bookshelves so we could see each painting clearly. Darrell explained how back in the 1940s, he had served as an advisor for the editor of Famous Fantastic Mysteries. Mary, the editor, had been looking for fantasy and science fiction novels to reprint in her magazine that had never appeared in magazine form in the USA before. Finding such stories was difficult, but Darrell and several other long-time SF readers provided Mary with books to reprint. In return, the grateful editor sent those fans original cover paintings done for the magazine. Which explained how the Rev. Richardson ended up with a half-dozen spectacular covers by some of the top artists in the sf field of the 1940s including Virgil Finlay and Lawrence Sterne Stevens. Darrell had also attended a number of early science fiction conventions where he had wisely bought art in the auctions usually held on the last day of the convention to help cover the hotel bill for the weekend.

Steve and I hoped to get some of Darrell’s paintings at bargain prices. However, the Reverend was not in a mood to sell stuff cheap. He insisted that we go over the price of each piece individually instead of making one deal for the entire lot of paintings. He wanted to get the highest price possible for the art. We wanted to pay the lowest possible price for the paintings. Darrell won.

Steve and I bargained as best we could, but Darrell had caught us in a clever trap. He knew that we wanted to buy or at least make some sort of deal to sell his book and pulp collection. But we had no idea what sort of price the Reverend wanted for his rarities. If we bought the books and pulps cheap enough, the profit we would make selling them would offset the price we paid for the art. No matter how much that cost might be. Still, trying to guess the amount of money Darrell wanted for his pulps and books was impossible. So we were buying paintings blind, with only vague hopes we would be able to recoup our payment.

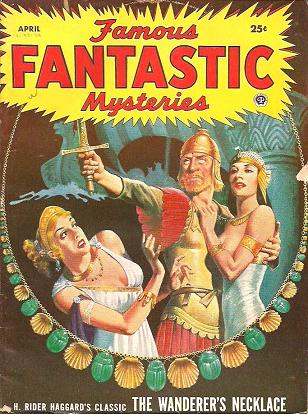

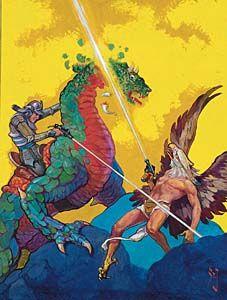

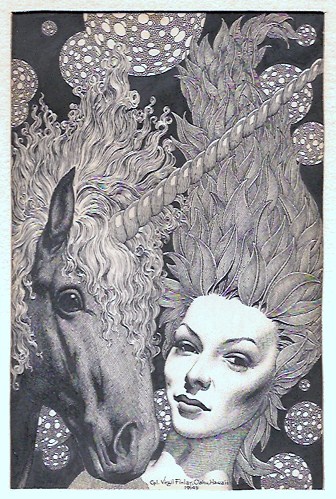

Making things worse was the fact that while Darrell had sold off all of his Tarzan paintings by St. John as well as the painting for “It’s a Small World” to Russ Cochran, he still owned another St. John Amazing Stories cover entitled “The Eagle Man.” Steve wanted that one. He also wanted “The Blue Tropics” painting done by Frank R. Paul. So did I, but I deferred to Steve on the selection. Instead, I had my eye on two pieces by Lawrence Sterne Stevens: “The Wanderer’s Necklace” (top of page, left) and “Dian of the Lost Land,” both of which had been used as covers for Famous Fantastic Mysteries.

Making things worse was the fact that while Darrell had sold off all of his Tarzan paintings by St. John as well as the painting for “It’s a Small World” to Russ Cochran, he still owned another St. John Amazing Stories cover entitled “The Eagle Man.” Steve wanted that one. He also wanted “The Blue Tropics” painting done by Frank R. Paul. So did I, but I deferred to Steve on the selection. Instead, I had my eye on two pieces by Lawrence Sterne Stevens: “The Wanderer’s Necklace” (top of page, left) and “Dian of the Lost Land,” both of which had been used as covers for Famous Fantastic Mysteries.

We bargained and bargained with Darrell, until we grew hoarse from shouting at him. In the end, we paid over $40,000 for the paintings we bought that afternoon. Steve and I got the paintings we wanted, but we paid near market price for them and couldn’t speak for a week afterward. We made a deal the next afternoon to sell Darrell’s book and pulp collection on consignment, but only the stuff from the Reverend’s old house. And not even all of that!

We didn’t get any of his spectacular pulp wall to sell, or any of the wonderful hardcover children’s books or Edgar Rice Burroughs first editions that lined Don’s shelves. Darrell’s nickname among Burroughs’ fans might have been the Old Tiger, but in our eyes, he was the Old Rattlesnake.

And we were his two latest victims!

For the record, Steve and I made very little money selling the books and pulps from Darrell’s house. Nowhere near enough to make a dent in the high prices we paid for the original art we obtained that weekend. Someday, if I ever get to writing my autobiography as a science fiction book dealer, I’ll devote an entire chapter to my dealings with the Reverend Richardson regarding this consignment sale. But that’s a long story that has nothing to do with art.

The Reverend Darrell Coleman Richardson died on September 19, 2006. He was a member of the generation of science fiction and fantasy art fans who saved and preserved art that otherwise most likely would have been destroyed or lost to the ravages of time. Despite all of my troubles and disagreements with Darrell, I enjoyed his company and conversation over the years that I knew him. He was a unique figure in the history of science fiction fandom.

~Three~

Fortunately, I had little time to nurse my wounds or cry about the way I had been treated by the Reverend. I had definitely spent more than I wanted and ended up with a lot more junk to sell than I had anticipated, but those were the breaks in making deals with old-time collectors. Most of the time, I made out like a bandit, buying paintings from elderly fans who hadn’t checked prices on artwork in twenty or thirty years. Still, every once in a long time, I encountered a sharp old character like the Reverend Richardson who demanded and got prices that were up to date. No one had put a gun to my head and forced me to pay him that money. I wanted the art and despite the high price, I had been willing to spend cash to get what I desired. Now that the Richardson deal was over, I had to immediately change gears and focus all of my attention on the next business at hand – the Sam Moskowitz auction in New York City. There was no time for tears, complaints, or regrets with such a major art event on the horizon.

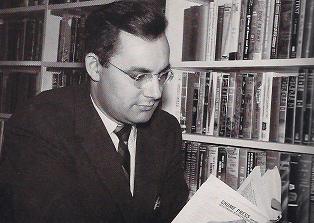

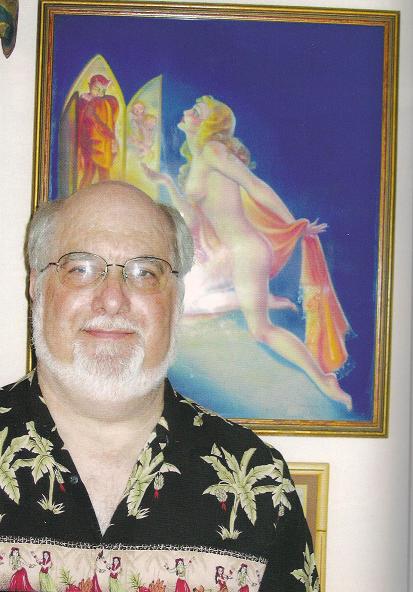

Sam Moskowitz (at left, circa late 1950s–early 1960s) was one of the premier science fiction fans and historians of the 20th century. It was Sam who had first treated science fiction as a genre worth exploring by academics, and if not for his early efforts, it was doubtful that any serious researchers would have ever devoted their attentions to the SF field. Sam owned one of the finest book and magazine collections in the science fiction field. He also owned a superb collection of original art by the legendary artist, Frank R. Paul from the late 1920s and early 1930s. How Sam had found the Paul paintings in the garbage in New York City was one of the most astonishing stories of original art collecting in the field. I covered that crazy adventure in depth in the second chapter of this memoir. I had been told that story by Sam Moskowitz himself, who I had known for many years as a friend and sometimes mentor in the SF field.

Sam Moskowitz (at left, circa late 1950s–early 1960s) was one of the premier science fiction fans and historians of the 20th century. It was Sam who had first treated science fiction as a genre worth exploring by academics, and if not for his early efforts, it was doubtful that any serious researchers would have ever devoted their attentions to the SF field. Sam owned one of the finest book and magazine collections in the science fiction field. He also owned a superb collection of original art by the legendary artist, Frank R. Paul from the late 1920s and early 1930s. How Sam had found the Paul paintings in the garbage in New York City was one of the most astonishing stories of original art collecting in the field. I covered that crazy adventure in depth in the second chapter of this memoir. I had been told that story by Sam Moskowitz himself, who I had known for many years as a friend and sometimes mentor in the SF field.

Sam (at right, MidAmeriCon, KC Worldcon, Sept. 1976) had died of a heart attack on April 15, 1997. He was 76. According to gossip prevalent at the time, Sam had not filed a will. Nor did he have any (or very little) life insurance. During the last decade of his life, Sam had struggled with cancer of the esophagus which I’m sure had made insurance impossible. Still, his wife, Dr. Christine Haycock, also a science fiction fan as well as a leading authority on women’s sports medicine, wasn’t hurting financially.

Sam (at right, MidAmeriCon, KC Worldcon, Sept. 1976) had died of a heart attack on April 15, 1997. He was 76. According to gossip prevalent at the time, Sam had not filed a will. Nor did he have any (or very little) life insurance. During the last decade of his life, Sam had struggled with cancer of the esophagus which I’m sure had made insurance impossible. Still, his wife, Dr. Christine Haycock, also a science fiction fan as well as a leading authority on women’s sports medicine, wasn’t hurting financially.

Sam and Chris lived in a huge doctor’s house in Newark, New Jersey, where Christine had her office, and Sam had his collection spread out everywhere else. The huge place was notable for having nine separate bathrooms! Plus, Sam had decorated all of the free walls with science fiction paintings. And, coffee table after table was filled with glass or china elephants, part of Chris’ collection of such figures.

It took Christine nearly a year to decide to sell a vast majority of the science fiction collection Sam had amassed. Mostly, she wanted to move into a smaller house, a place easier to manage, and one not filled with paintings, books, and pulp magazines wherever you looked. After considering offers from various science fiction book dealers and several major auction houses, she decided to sell Sam’s collection at an auction held by Sotheby’s in New York City.

Sotheby’s specialist in science fiction and comic books was my friend and frequent art customer, Jerry W. He spent the next year preparing for what was to be one of the biggest and most exciting science fiction book, pulp, and art auctions ever held in New York. The auction took place on Tuesday, June 29, 1999. There were approximately 300 lots of items in the entire auction. On Monday of that same week, Sotheby’s ran a comic book and comic art auction, with close to 500 lots in that auction. Needless to say, many of the comic book investors and dealers who came in for the first auction stayed for the Sam Moskowitz auction. Along with them, many of the most famous collectors and book dealers of science fiction came to New York for the second auction. I was there, though I had little hope of buying anything major at the Moskowitz sale. The adventure in Memphis with the Reverend Richardson had nearly wiped me out of money to be spent on art. And I surely did not expect there to be any bargains when the top collectors and dealers in science fiction were in the room.

Among the many well known buyers there were Stuart S, Robert W, David A, Howard and Jane, LWC, and John K. There were even collectors and dealers from England in the room. It was a virtual who’s who of science fiction collecting. And, for those collectors who could not make the auction in person, there were several phone lines enabling buyers to bid by telephone.

However, as is often the case in the competitive world of art collecting, not all of the best art available was offered in the auction. Robert L, who had never had any luck dealing with Sam Moskowitz when Sam was alive, contacted Christine soon after Sam’s death. He told her that he was really, really hoping that he could buy an early Frank R. Paul painting from Sam’s collection to go with his huge holding of pulp covers. Robert, who had been buying Paul paintings for years from Forrest J Ackerman, appealed to Chris on an emotional level, dwelling on the fact that they both had been Phi Beta Kappa scholars. Further, he mentioned how his collection was destined for a museum someday and that it only seemed proper that one of the paintings Sam rescued should end up in a museum, and not merely in a private collection. So, Chris had sold Mr. L one of the best Paul paintings long before Jerry W. ever contacted her.

What made Mr. L’s purchase even more annoying was the fact that when Christine decided to let Sotheby’s mount an auction of Sam’s collection, she specified that she would only sell three Frank R. Paul early Wonder Stories cover paintings in the auction. She wanted to see how they sold before committing other cover paintings to Sotheby’s.

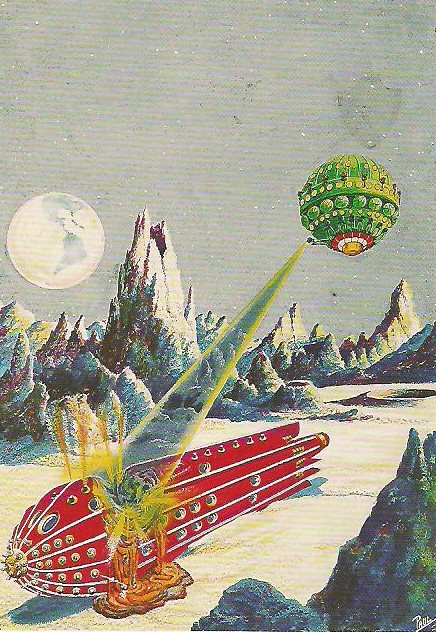

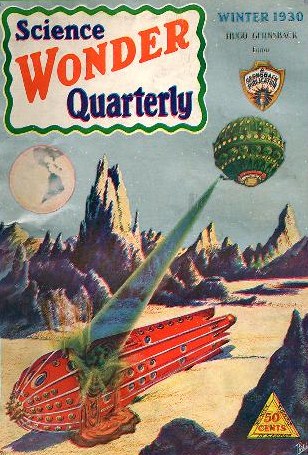

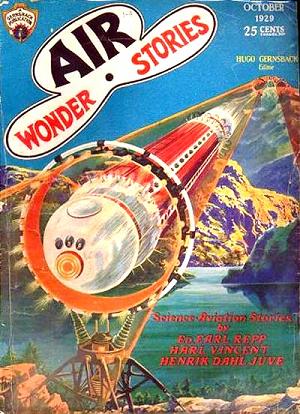

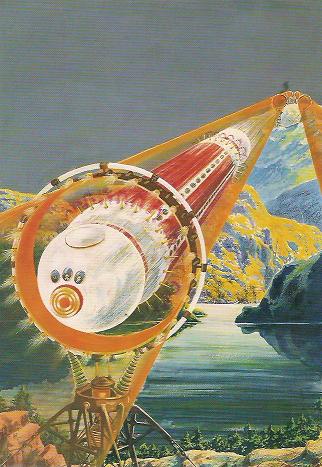

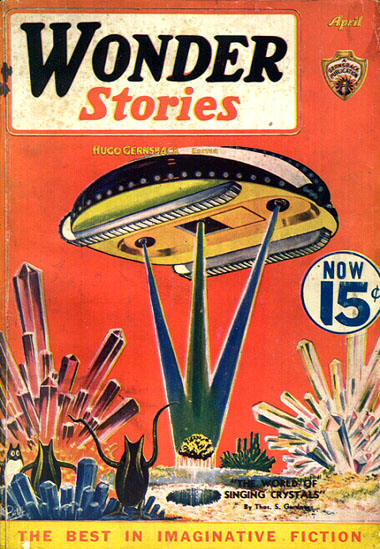

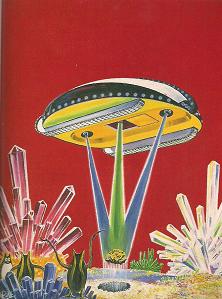

Christine also specified that she was the ultimate decision maker when it came to selecting the paintings for the sale. Needless to say, while the three paintings she selected were good pieces, they were not the top originals of the Moskowitz collection. Only one of the pieces, the cover for Science Wonder Quarterly from Winter 1930 sold for better than the estimated price. The piece, valued between $20,000 – $40,000 sold for $67,500. The second Paul cover offered for sale in the auction was the painting for Air Wonder Stories, October 1929. Estimated at a value between $20,000 to $40,000, it sold for only $20,000. The third color Paul painting in the auction was the cover for Wonder Stories, April 1936. It was estimated to sell for between $15,000 and $20,000. It only brought in $15,000. Altogether, the three Paul paintings from the Wonder group sold for approximately $100,000, but if hadn’t been for the Quarterly cover selling for an extraordinarily high price (the result of a bidding war between two collectors), the sale would have been judged a disaster. As it was, Christine Haycock decided not to sell any more of her Frank R. Paul Wonder Stories covers at any future auctions.

Christine also specified that she was the ultimate decision maker when it came to selecting the paintings for the sale. Needless to say, while the three paintings she selected were good pieces, they were not the top originals of the Moskowitz collection. Only one of the pieces, the cover for Science Wonder Quarterly from Winter 1930 sold for better than the estimated price. The piece, valued between $20,000 – $40,000 sold for $67,500. The second Paul cover offered for sale in the auction was the painting for Air Wonder Stories, October 1929. Estimated at a value between $20,000 to $40,000, it sold for only $20,000. The third color Paul painting in the auction was the cover for Wonder Stories, April 1936. It was estimated to sell for between $15,000 and $20,000. It only brought in $15,000. Altogether, the three Paul paintings from the Wonder group sold for approximately $100,000, but if hadn’t been for the Quarterly cover selling for an extraordinarily high price (the result of a bidding war between two collectors), the sale would have been judged a disaster. As it was, Christine Haycock decided not to sell any more of her Frank R. Paul Wonder Stories covers at any future auctions.

That’s not to say she didn’t sell any other of her Paul artwork. As was often the case when an owner didn’t receive the price they considered proper for their items at auction, Christine resorted to private sales to move several of her other originals. A small number of her very best Paul paintings were sold in the months following the auction to interested collectors with the funds necessary to meet Chris’s price. Even Jerry W, who had arranged for the Moskowitz auction, couldn’t resist the lure of a painting that Dr. Haycock had refused to put in the sale but offered on her own afterwards. He bought it a few months after the auction was over. The piece in question was Virgil Finlay’s spectacular cover for the January 1941 issue of Fantastic Novels illustrating “The Radio Beasts” by Ralph Milne Farley. Many collectors considered that painting, with a man flying a gigantic bee, to be one of best SF covers ever to appear on a pulp magazine.

That’s not to say she didn’t sell any other of her Paul artwork. As was often the case when an owner didn’t receive the price they considered proper for their items at auction, Christine resorted to private sales to move several of her other originals. A small number of her very best Paul paintings were sold in the months following the auction to interested collectors with the funds necessary to meet Chris’s price. Even Jerry W, who had arranged for the Moskowitz auction, couldn’t resist the lure of a painting that Dr. Haycock had refused to put in the sale but offered on her own afterwards. He bought it a few months after the auction was over. The piece in question was Virgil Finlay’s spectacular cover for the January 1941 issue of Fantastic Novels illustrating “The Radio Beasts” by Ralph Milne Farley. Many collectors considered that painting, with a man flying a gigantic bee, to be one of best SF covers ever to appear on a pulp magazine.

Speaking of the best art by Virgil Finlay, in the second chapter of this memoir, second section, I mentioned how in the late 1960s, Sam Moskowitz visited Virgil Finlay at his home in Long Island. Sam looked at the several thousand original illustrations Finlay had in files at his house, but he bought only one piece, feeling it was the best thing Finlay had ever done. The black-and-white illustration was of a woman with a unicorn, and the artist had drawn it while on Okinawa in the Pacific during World War II. I had seen the Finlay at Sam’s house a number of times when I visited him during the years I had lived on the East Coast. I agreed that it was one of the best pieces Finlay had ever created. I dreamed of owning that original for thirty-five years. I finally got my chance in 1999. Which brings me at long last to the second deal made possible by my work for the Church of Scientology.

Speaking of the best art by Virgil Finlay, in the second chapter of this memoir, second section, I mentioned how in the late 1960s, Sam Moskowitz visited Virgil Finlay at his home in Long Island. Sam looked at the several thousand original illustrations Finlay had in files at his house, but he bought only one piece, feeling it was the best thing Finlay had ever done. The black-and-white illustration was of a woman with a unicorn, and the artist had drawn it while on Okinawa in the Pacific during World War II. I had seen the Finlay at Sam’s house a number of times when I visited him during the years I had lived on the East Coast. I agreed that it was one of the best pieces Finlay had ever created. I dreamed of owning that original for thirty-five years. I finally got my chance in 1999. Which brings me at long last to the second deal made possible by my work for the Church of Scientology.

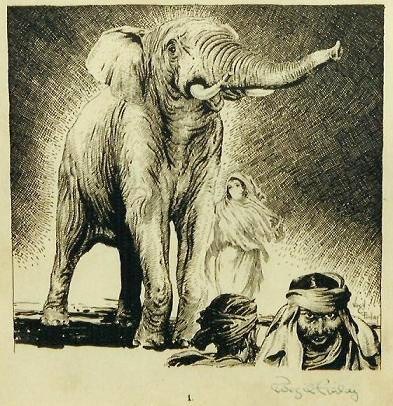

Working for the Scientologists, I specified that I wanted as part of my compensation one of the Finlay originals they owned. The piece was part of the treasure trove of artwork they gave to me to use to bargain for L. Ron Hubbard paintings (see last month’s memoir for details of that adventure). The Finlay illustration was for the story, “Death is an Elephant,” that appeared in the Feb. 1939 issue of Weird Tales. The terrific art centered on a massive elephant drawn by Finlay. I knew it was an illustration that Christine Haycock, a die-hard elephant collector would have to have once she saw it. So, I passed the art along to my friend, Jerry W, with instructions that he was only to trade it to Christine for the unicorn original by Finlay. The deal progressed smoothly and I received the Okinawa illustration late in 1999. It made a wonderful Christmas present to myself.

Dr. Christine Haycock, Sam Moskowitz’s widow, died after a short but deadly illness on January 23, 2008. Her estate, including the remaining Frank R. Paul paintings, is being handled by a nephew.

Dr. Christine Haycock, Sam Moskowitz’s widow, died after a short but deadly illness on January 23, 2008. Her estate, including the remaining Frank R. Paul paintings, is being handled by a nephew.

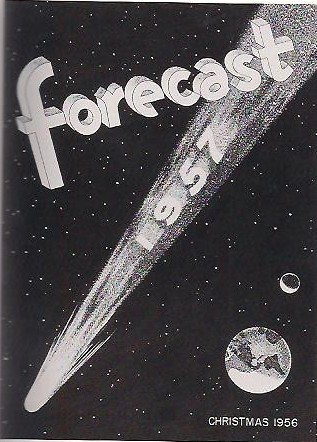

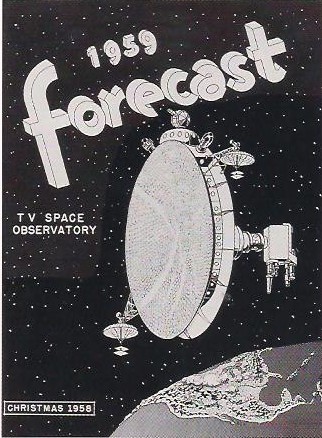

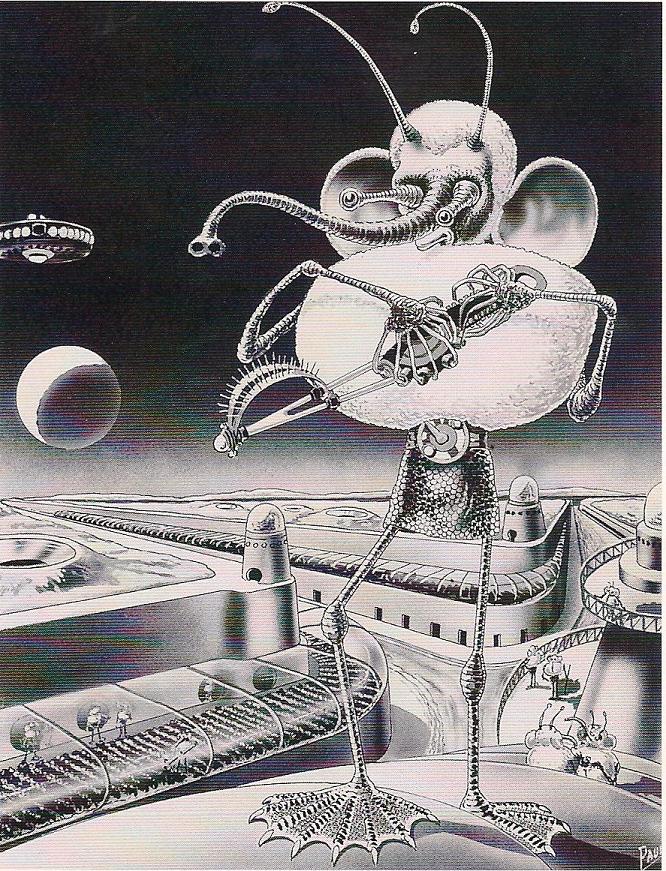

Getting back to the Moskowitz auction: while the three color Paul paintings from the 1930s didn’t do as well as expected, most everything else in the auction sold. Some of the items sold for the minimum suggested price while a number of items sold for the high estimate. Sam owned all of the Frank R. Paul artwork used in Forecast, a small magazine published each year in the 1950s and 1960s at Christmas time by Hugo Gernsback (see Showcase below). The black-and-white covers for various issues of the magazine sold for approximately $1,000 each. Other Paul art and originals for Finlay and Alex Schomburg sold for reasonably high prices. I didn’t bid on any of the art. I had come to New York looking for a bargain in artwork. There were no art bargains at the Moskowitz auction. I didn’t care. I had scored already and the Moskowitz auction was just a vacation.

My art buy of the week had come at the comic book auction held at Sotheby’s the day before the Moskowitz auction. I had spotted an interesting listing in the catalog for the auction. Included in the sale were numerous pieces of artwork once owned by Kevin Eastman (co-creator of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles). Along with comic book originals, Eastman also was a fan of science fiction and fantasy art. Auctions featuring art from his collection often had misc. sf and fantasy originals for sale among the listings. Moreover, since the only people who frequented comic book auctions were comic book fans, the sf art rarely sold or if it did, went for low low prices.

Playing a hunch, I went to that Monday auction. I was one of only a very few science fiction collectors present at the sale. The piece I was interested in went up for sale fairly early in the auction. In the catalog, the art was listed as “two originals by Roy Krenkel.” Both illustrations were described as preliminary works. One piece, a color rough, was called “Inside the Harbor,” while the other, a pen-and-ink sketch, was titled “Pellucidar.”

Fortunately, I knew Krenkel’s art pretty well. The color rough listed as “Inside the Harbor” was no rough. Instead, it was the finished painting done for the 7 Wonders of the Ancient World, a Roy Krenkel portfolio. The art illustrated the wonder known as the Colossus of Rhodes. The “Pellucidar” pen and ink illustration was a bonus, one of Roy’s fine sketches of cave men and women and dinosaurs. Separately, I valued it at $500. The Krenkel painting I felt was easily worth $5,000 at the time. Twelve years later, I think it has increased five times in value.

Fortunately, I knew Krenkel’s art pretty well. The color rough listed as “Inside the Harbor” was no rough. Instead, it was the finished painting done for the 7 Wonders of the Ancient World, a Roy Krenkel portfolio. The art illustrated the wonder known as the Colossus of Rhodes. The “Pellucidar” pen and ink illustration was a bonus, one of Roy’s fine sketches of cave men and women and dinosaurs. Separately, I valued it at $500. The Krenkel painting I felt was easily worth $5,000 at the time. Twelve years later, I think it has increased five times in value.

I bought both pieces for $1,000. If there hadn’t been one annoying fan in the audience, I would have gotten the art for half that price. Still, I was quite satisfied with my purchase. Later, in that same auction, I bought three paintings by Tom Kidd used as covers for 1980s Questar science fiction paperbacks. I was the only person interested in these and I got them for minimum bid, approximately half of the lower estimate of the value of each piece. I recently sold the three for about double what I paid for them. Which doesn’t take into account the dozen years of pleasure I got out of looking at the pieces hanging on the walls of my home. The Krenkel Colossus painting is framed and hanging in my television-room/library. Not a day goes by without me looking at the piece and thinking back to the Moskowitz auction.

In retrospect, many art collectors consider that auction one of the turning points of modern science fiction art collecting. While not the first auction in which science fiction art was offered and sold for healthy prices, it was perhaps the most notable and most publicized of such auctions. The Moskowitz sales established the fact that good SF art could bring high prices. It also made it clear that the art of Frank R. Paul, though primitive in a fashion, was still extremely collectible.

Most of all, the Moskowitz auction was the start of science fiction art’s spectacular leap in prices. Collectors finally realized that original illustrations and paintings by science fiction’s best artists were worth buying, not only for content but for investment possibilities. It was the beginning of a trend that has continued, gathering momentum month by month, to this day.

~Frank R. Paul Showcase~

(Forecast covers and illo from Sam Moskowitz auction)

~Next Time~

Column #10

Party Time!

Robert Weinberg is the author of 17 novels, 16 non-fiction books and around a hundred short stories. He’s also edited over 150 anthologies. He owns one of the finest SF/Fantasy original art collections in the world. These days, Bob is busy promoting his new book, Hellfire: Plague of Dragons, done with artist Tom Wood, and serving as editor for Arkham House publishers.

Article and art copyright © 2011 by Robert Weinberg and Tangent Online.

1976 Sam Moskowitz photo copyright © David A. Truesdale. All rights reserved.