Collecting Fantasy Art #8:

Collecting Fantasy Art #8:

Sam and the Scientologists

By Robert Weinberg

Copyright © 2011 by Robert Weinberg

~One~

When I first started writing these articles detailing my adventures in collecting science fiction art, I assumed I would have no problems remembering when every deal of importance took place in my nearly forty years as an art enthusiast. I am notorious among my family and friends for having an exceptional memory. In particular, I know the history of nearly every painting and black-and-white illustration hanging on the walls in my house. Usually, I can recall in great detail how I bought or traded for a piece and where it originally appeared in print. I love talking about my art collection, so I felt confident it would be easy to recount my triumphs and disasters buying and selling original art. Needless to say, it has proven to be much more of a challenge than I expected.

Why much more? Because, though my memory is quite good and most details about deals and trades are still fresh in my mind, I never paid much attention to the dates or times when those paintings were acquired. Nor did it ever occur to me that someday I might compose my autobiography. So I never took any notes regarding those deals and trades, nor did I itemize expenses spent on paying for the artwork involved. Thus, I still remember the person from whom I got the artwork, along with the details of the transaction. But, I don’t remember exactly when those deals happened.

I mention this because I do have a tendency in these columns to drift from one year to another in the course of a paragraph or two. It’s not because I don’t want to maintain a strict sequential order in the stories I relate about the great art deals I’ve been involved with over the course of five decades. It’s just that sometimes I honestly don’t remember when the events took place. Besides, sometimes, an art purchase or trade only makes sense if it refers back to another deal made fifteen or twenty years previously. Or, if some how, some way, the deal hinges on a seemingly innocent remark made in a letter or conversation a half-century before. Collecting is an adventure as complicated and mysterious as any thriller novel. And the stakes are of equal value, just on a smaller scale.

So please excuse my drifting through time in previous columns and in the column that follows this brief little introduction. Many of the deals that yield the best results are due to remembering something said or seen years and years earlier. For those who wonder how I managed to assemble such a large collection of original golden age science fiction art, much of my luck is due to my remarkable memory. I think by the time you finish reading the next few columns, you’ll agree with me.

~Two~

One of the unspoken secrets of assembling a great art collection is to live longer than your friends in the field. That’s a good trick, especially if all of your friends who collect art are younger than you. But, crazy as it sounds, there’s a grain of truth in the statement. Most of the major science fiction art collections in the United States are owned by collectors older than sixty. Live long enough and the choice of great art for sale is going to be incredible.

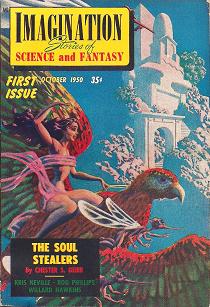

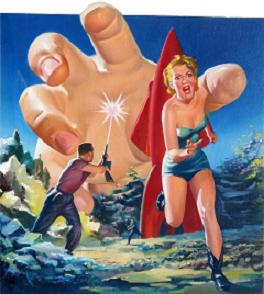

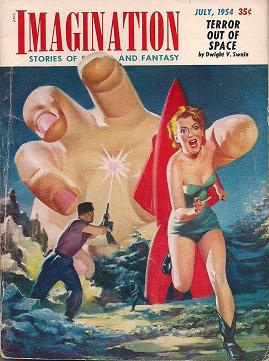

In the first column of this series, I described attending PULP-con #2, held in Dayton, Ohio in 1973. I volunteered to run the small pulp art show at the convention, and I brought most of the paintings from my own small collection. I also displayed a number of originals I borrowed from several friends. However, the big hit of the display was a bunch of SF paintings brought by science fiction book dealer Ben Jason. The treasure trove included three Frank R. Paul color originals, two from Wonder Stories in the 1930’s, as well as the cover painting for the Cleveland World SF Convention in 1955 (tall city building, lower left). Ben also brought with him an H.W. McCauley painting, a cover for Imagination magazine from 1954 illustrating “Terror Out of Space” by Dwight V. Swain, and a Malcolm Smith cover for Imagination for “Slaves to the Metal Horde” also from 1954. All five of the paintings sold that weekend, two at auction and the other three in private sales. I bought one of the Paul pieces, a Wonder Stories cover from 1930 for “The Time Annihilator” that my wife particularly liked. I also made a mental note who got the other originals. Just in case, I said to myself. Just in case they ever got tired of their paintings. Improbable but not impossible.

In the first column of this series, I described attending PULP-con #2, held in Dayton, Ohio in 1973. I volunteered to run the small pulp art show at the convention, and I brought most of the paintings from my own small collection. I also displayed a number of originals I borrowed from several friends. However, the big hit of the display was a bunch of SF paintings brought by science fiction book dealer Ben Jason. The treasure trove included three Frank R. Paul color originals, two from Wonder Stories in the 1930’s, as well as the cover painting for the Cleveland World SF Convention in 1955 (tall city building, lower left). Ben also brought with him an H.W. McCauley painting, a cover for Imagination magazine from 1954 illustrating “Terror Out of Space” by Dwight V. Swain, and a Malcolm Smith cover for Imagination for “Slaves to the Metal Horde” also from 1954. All five of the paintings sold that weekend, two at auction and the other three in private sales. I bought one of the Paul pieces, a Wonder Stories cover from 1930 for “The Time Annihilator” that my wife particularly liked. I also made a mental note who got the other originals. Just in case, I said to myself. Just in case they ever got tired of their paintings. Improbable but not impossible.

The first of those four paintings that were sold to other collectors came back to me in the mid-1980’s. It happened soon after I bought a large number of air war paintings by Frederick Blakeslee, as described in column 4. Lynn Hickman, a well-known pulp fan who lived in Ohio, was a big fan of the air war pulps, as well as a well-known science fiction art collector. I had known Lynn for years, having met him back at the 1967 World Science Fiction Convention in New York City. He was a truly nice guy with a sly sense of humor. Lynn had been collecting artwork from the pulp fiction magazines since the 1940’s. Along with a number of spectacular SF paintings, Lynn owned an original cover painting for Black Mask magazine. I knew that Lynn really wanted a Frederick Blakeslee air-war painting.

The first of those four paintings that were sold to other collectors came back to me in the mid-1980’s. It happened soon after I bought a large number of air war paintings by Frederick Blakeslee, as described in column 4. Lynn Hickman, a well-known pulp fan who lived in Ohio, was a big fan of the air war pulps, as well as a well-known science fiction art collector. I had known Lynn for years, having met him back at the 1967 World Science Fiction Convention in New York City. He was a truly nice guy with a sly sense of humor. Lynn had been collecting artwork from the pulp fiction magazines since the 1940’s. Along with a number of spectacular SF paintings, Lynn owned an original cover painting for Black Mask magazine. I knew that Lynn really wanted a Frederick Blakeslee air-war painting.

I was getting $1,000 each for the air war pulp covers and I knew that Lynn wouldn’t pay that sum of money for a pulp cover, no matter who it was by. Still, I knew he wanted to own one of the paintings. So, I traded him his choice of the Blakeslee’s for the McCauley Imagination cover. I knew that Lynn had bought the H.W. McCauley painting that Ben Jason brought to PULP-con #2 for $59. I had paid more than that for each of the 21 air war paintings I obtained from the man in New Jersey. But, not a lot more. My costs per painting were approximately double what Lynn paid for the McCauley. What I realized in proposing a trade with Lynn Hickman was the original cost of a painting didn’t matter in a swap. All that counted was how much the art was worth at the time of the new deal. Lynn’s McCauley was worth $1,000 as was my Frederick Blakeslee painting. All previous prices were unimportant.

That McCauley was the first of the Ben Jason paintings I had witnessed sold at PULP-con #2 that I was able to obtain years later for my collection. It was not the last.

The second piece from that same convention was offered to me in the mid-1990s. My friend, Stuart S., had bought the cover for the Cleveland World SF Convention of 1955, painted by Frank R. Paul at the pulp convention in Dayton. The paperbound convention book was the first ever to feature a color cover, and the Paul painting done especially for the con program book was spectacular. Stuart collected all sorts of interesting memorabilia, not just science fiction, and oftentimes he sold pieces from his collection to help pay for something else that he wanted more. I suspect that was the case regarding the Paul.

At the auction at PULP-con #2, Stuart bought the painting for little more than $100. Approximately twenty years later, I paid him more than twenty-five times as much for the original. We both were happy with the deal. It was the second piece I got from the Ben Jason sale at PULP-con #2. There were still two other pieces out there – a wonderful Malcolm Smith robot cover and a green Frank R. Paul painting from Wonder Stories. One collector owned them both. Someday, perhaps he would want to sell them. If he did, I was interested.

In both cases, I didn’t outlive the other collector involved in the trade. What I did do was remain interested in the original long after their interest in the painting they owned died. While they were still alive, their love of the art had perished. So, in a manner of speaking, I had outlived their interest in the specific painting.

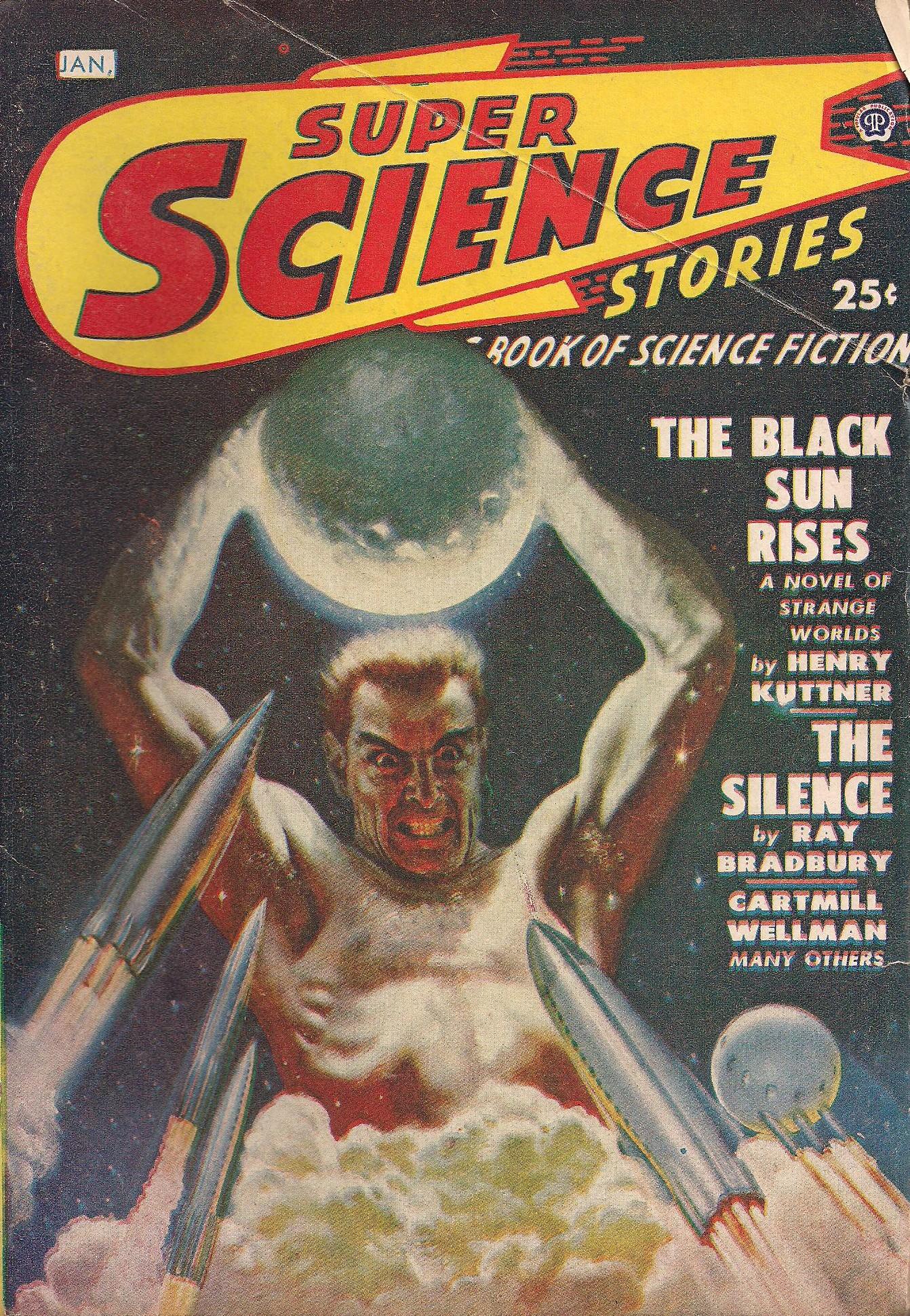

Mentioning Lynn Hickman brings back many fine memories. Lynn began collecting art back in the 1940’s. One of the earliest paintings he acquired was the cover for the January 1949 issue of Super Science, an original by Lawrence Sterne Stevens inspired by the title of the lead story in that issue, “The Black Sun Rises.” The art was spectacular and Lynn displayed the piece several times at PULP-con. From the first time I saw it, I knew that someday I had to own it. Not being shy, I asked Lynn if he would sell it to me. He wouldn’t think of it. But, smiling, he promised me that when he died, he would instruct his wife to let me buy it.

Mentioning Lynn Hickman brings back many fine memories. Lynn began collecting art back in the 1940’s. One of the earliest paintings he acquired was the cover for the January 1949 issue of Super Science, an original by Lawrence Sterne Stevens inspired by the title of the lead story in that issue, “The Black Sun Rises.” The art was spectacular and Lynn displayed the piece several times at PULP-con. From the first time I saw it, I knew that someday I had to own it. Not being shy, I asked Lynn if he would sell it to me. He wouldn’t think of it. But, smiling, he promised me that when he died, he would instruct his wife to let me buy it.

Lynn died in the late 1990s. The next summer, his wife and son invited a bunch of art collectors over to their house one night of PULP-con. They offered nearly all of the paintings in Lynn’s collection to the highest bidders. Everything was for sale except for one piece, the January 1949 Super Science cover. That original, they told everyone, was reserved for me. Lynn had remembered his promise, made half-jokingly several decades earlier. I paid his family a fair price for the piece and it has remained in my collection ever since. It is one of my favorites, not only because it is great art, but because it reminds me of a good friend.

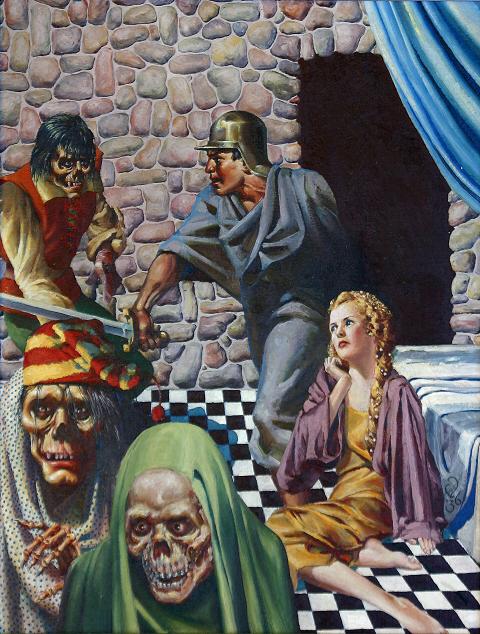

I should mention that Lynn’s greatest art treasure was the cover for the October 1950 issue of Imagination for Chet Geier’s story, “The Soul Stealers” painted by Hannes Bok. The Bok painting was magnificent and many collectors consider that piece his finest original. Lynn got the art from the assistant editor of Imagination, who kept it in her collection for many years. As he told me, he waited twenty years to get it and it was well worth the wait.

I should mention that Lynn’s greatest art treasure was the cover for the October 1950 issue of Imagination for Chet Geier’s story, “The Soul Stealers” painted by Hannes Bok. The Bok painting was magnificent and many collectors consider that piece his finest original. Lynn got the art from the assistant editor of Imagination, who kept it in her collection for many years. As he told me, he waited twenty years to get it and it was well worth the wait.

After Lynn’s death, I negotiated the purchase of the Bok painting for one of my regular clients who wanted to keep his identity secret. This collector paid an extremely fine price for the Bok original. After owning the piece for several years, the new owner decided he didn’t like the painting as much as he thought he would. So, he decided to sell or trade it. I learned of his intent and made a trade offer that he accepted. I obtained the painting and it has been one of the highlights of my collection for the past ten years.

~Three~

Another unspoken secret of collecting rare science fiction art (or any other art for that matter, though the secret works best for science fiction) is to get all the publicity you can about your collection and how much money you are willing to spend on rare or unusual art. The better known you are, the more art comes your way. Especially from people you never would have encountered otherwise.

Now, most collectors are worried about advertising their collections, particularly among people who know the value of the art or its scarcity. Fortunately, science fiction fans who collect original art are rarely professional thieves. Nor do art fans associate with notorious cat burglars. So the chance of any of these other collectors stealing the advertiser’s collection of masterpieces is pretty much zero.

Still, many collectors feel that any publicity about their collection is a bad idea. Advertising their rare items they feel is the same as erecting a huge billboard with a glowing neon arrow on it pointing straight at your house, with the words “here’s the treasure!” painted in big red letters beneath it. As collectors, we are a paranoid breed. Even though, deep down in our hearts we know that if someone broke into our house they would ignore the paintings on the walls and instead haul off the plasma TV and the microwave oven.

No real thief is foolish enough to steal artwork which is easy to identify as stolen and nearly impossible to sell on the black market. Thieves stick to the things they know are nearly impossible to identify and sell instantly on the black market. We are talking electronics, not science fiction paintings. In my forty years of collecting art, I have only heard of one or two originals ever being stolen, and those cases involved messy divorces and angry ex-spouses. So discussing your collection in public is really not dangerous nor is it the same as inviting thieves in to your house, Breathe easy my friends.

Big publicity generates big deals. The secret rule is simple to remember. The better known you are as an art collector, the greater the chance that you’ll hear from people who want to sell their collections. It happens all the time. But it only happens to people whose name is well-known among art collectors. This is a hobby where being shy doesn’t pay. In collecting, the loudest voice is very often the person with the best collection.

Now, I am, believe it or not, fairly soft-spoken and quiet. I like to talk, no question about that, but I am usually pretty quiet around strangers. I only open up and talk at length with people I know. Yet, I do realize the importance of publicity and of publicizing your collection. So, I write articles and essays about collecting art. Articles just like this one that you are reading. Plus, I write all sorts of essays about authors and art and the close relationship between the two; about the importance of art to science fiction; about the lives and times of famous artists and their work; and anything else I can think of that will get noticed and get read by art fans and collectors. Along with essays and articles, I’ve even written books discussing in depth the history of science-fantasy publishing, and a reference book of biographies and checklists of science fiction and fantasy artists. This work all serves as ways of publicizing my interest in original art and my intense desire to collect it. I make it quite clear in all of my writing that I am still collecting art and that I pay high prices for good pieces. I’m not subtle, but subtle people rarely buy collections. Judging by the size and depth of my holdings, my efforts have paid off.

Other collectors have tried similar methods with varying degrees of success.

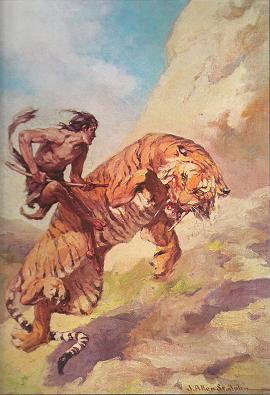

Perhaps the most successful of these attempts was conducted by my friend, Steve K.. Steve grew up with a J. Allen St. John original cover painting from Amazing in his bedroom. It was a gift from his father who had divorced Steve’s mother years before. Not surprisingly, Steve grew up to become a huge science fiction art fan, with a special taste for St. John, a classically trained artist who painted many of the color and gouche oil paintings used to illustrate the hardcover books of Edgar Rice Burroughs. St. John was considered by most old-time Burroughs collectors to be the finest artist ever to illustrate the Tarzan novels. His paintings sold for many thousands of dollars in a time when pulp magazine cover paintings were bringing fifteen or twenty dollars on the open market.

In 1996, Steve decided to travel around the USA visiting art collectors throughout the country, with hopes of getting them to sell him one or more of their prized originals. To me it sounded like a crazy idea, but Steve was convinced it might work. He felt certain that most collectors had never been offered thousands of dollars for the paintings in their collections. Steve was convinced that high prices would shake artwork loose from a number of collectors who swore they would never sell anything. It was much the same philosophy that Bob Lesser had expressed when he started collecting rare paintings, and it had served Lesser well. In the period of approximately ten years, he bought nearly a hundred pulp paintings, many of them science fiction and fantasy masterpieces, from collectors who swore they would never ever let anything go from their collection. Big money spoke with a big, loud voice in the science fiction field. Steve K. was determined to match Bob Lesser’s achievements and do him one better.

Steve owned his own law firm so was able to dictate his own work schedule. Off and on through 1996, he traveled to various parts of the country, where he visited well-known original art collectors and saw their collections. He traveled with his father, EK, who knew many of the old-time collectors from the period when he was a dealer and publisher in the science fiction field. That they were scouting art, hoping that someone might mention they wanted to sell one of their finest paintings, was never mentioned. But the thought was there.

Steve called me from time to time from the road to tell me about his latest adventure and describe the paintings he had seen. He liked talking about good art and I was one of the few people who he knew he could trust not to reveal any of his collecting secrets. We were good friends and I always listened to his stories with a sympathetic ear and a quiet enthusiasm about the art he saw. Steve visited numerous collectors in the south, the Midwest, and the southwest. Though he did get to see a lot of great paintings, very few of them were for sale. Steve bought a few nice items, but not many. It was just as I expected. What I did not expect was Steve’s phone call in the middle of the summer of 1996.

Steve and EK had traveled to California to visit the famous book and magazine collector, Sam Peeples. Sam was well known among science fiction fans for owning one of the finest collections of rare pulp magazines and science fiction hardcover books. A noted western author, he owned one of the finest Zane Grey book collections in the world. He also owned one of the best collections of Edgar Rice Burroughs first edition hardcover books in the country. Sam owned one St. John Burroughs painting, done for the novel, The Eternal Lover. The piece, which showed a caveman fighting a saber-tooth tiger, was a spectacular illustration.

Steve and EK had traveled to California to visit the famous book and magazine collector, Sam Peeples. Sam was well known among science fiction fans for owning one of the finest collections of rare pulp magazines and science fiction hardcover books. A noted western author, he owned one of the finest Zane Grey book collections in the world. He also owned one of the best collections of Edgar Rice Burroughs first edition hardcover books in the country. Sam owned one St. John Burroughs painting, done for the novel, The Eternal Lover. The piece, which showed a caveman fighting a saber-tooth tiger, was a spectacular illustration.

Outside the science fiction field, Sam Peeples was famous for being a television and movie producer. During the 1950s, Sam had served as the producer of a half-dozen different western shows. One year, four of his shows made the top ten watched shows on TV week after week. In movies, Sam was well-known as the producer of the film Walking Tall. Before he got into producing, Sam served as sheriff of Los Angeles. Before that, he had written dozens of western novels. And before that, he had been a performer in the circus. Sam Peeples was as amazing a character as any person in one of his novels.

Steve visited Sam Peeples in the summer of 1996 with hopes that Sam might consider selling his St. John painting. Sam, to Steve’s surprise, was willing to sell him the piece. But, Sam liked Steve, so he made him a counter-offer, a deal much better than just the sale of one painting. Sam was willing to sell Steve the St. John painting for a fair price in the thousands of dollars. However, if Steve was interested, Sam was willing to sell Steve his entire science fiction and fantasy book and magazine collection along with the St. John painting for double the price of the art. Thus, Steve could buy the painting for X amount of money. Or Steve could buy the painting and Sam’s huge SF collection for 2X the amount.

It seemed like a great deal, but Steve was a lawyer and as such was extremely careful spending thousands of dollars. So he called me, told me the terms of the deal, and asked me what I thought of the offer. Steve knew I bought and sold rare science fiction and fantasy material all the time as part of my regular business. And I was conservative in my pricing, so I valued rare items at what they were actually worth, not what I hoped they were worth.

After hearing the details of the offer, I told Steve it sounded like a tremendous opportunity, though it was hard for me to judge the actual value of everything without seeing the collection in person. Steve thanked me and told me I would hear from him shortly.

A few days later I got another call from Steve. He was back in his law offices in Florida, working on a few cases that required his attention. He planned to visit Sam Peeples for a second time, along with his father EK, in the next few weeks. He wanted me to come along with them, and he would pay my way. He wanted me to examine the collection before he bought it and make sure everything was as good as I expected. It was all part of his master plan.

Steve wanted to buy Sam Peeples’ collection for resale. The catch was that he wanted me to sell it for him. Steve would put up the money for the purchase but he was no book dealer. Instead, I would handle all of the work selling the collection. We would be partners in the profits, once Steve earned back the cost of the books. He would keep the St. John painting since he would be paying for it.

It sounded like a fair deal to me and I agreed to help Steve with the Peeples collection. When we arrived at Sam’s house in California, it turned out that Sam already knew who I was. He had read my book on the history of Weird Tales magazine and was familiar with my many articles on collecting art. While he was hoping that Steve would hang onto some of the rare books in his collection, he was pretty much aware of the fact that Steve was buying the magazines and hardcovers to resell them. And that I was acting as Steve’s partner in the task.

Sam knew that Steve was buying his science fiction collection as a way to get his St. John painting for next to nothing. Steve hoped to sell Sam Peeples’ books and magazines for double what he paid for them, thus raising enough money to cover the costs of the art and the books. I thought Sam was being overly generous with Steve. I should have realized that there was a reason Sam was doing what he was doing.

In any case, Steve, his father, and I arrived at Sam Peeples home late Thursday evening. After brief introductions were made, I got to look for a short while at the book collection. Then, the three of us left for our hotel, with the next day planned as our first big work day. I won’t go into the details of packing and shipping Sam Peeples’ huge collection back to my house via truck, other than to say that getting everything boxed up securely almost resulted in my having a nervous breakdown. Steve and his father EK were both lawyers and knew very little about packing huge collections. Thus, I was responsible for getting all of Peeples’ vast holdings ready for shipment on the following Monday. It wasn’t nearly enough time, especially when working with two inept assistants. But that’s not a story for my adventures collecting art. What mattered was the phone call I received at Sam’s home that Friday.

We had broken for lunch and I was devouring a sandwich when the phone rang in the kitchen. Sam’s wife picked up the receiver, and after listening for a moment, handed the phone to me. “It’s for you,” she said.

I was surprised. The only person who knew where I was, was my wife. And I didn’t expect to hear from her until the evening, when I was back at our hotel rooms. I took the phone and spoke into the receiver.

“This is Bob Weinberg.”

“Mr. Weinberg,” said the voice on the other end of the line. “Your wife gave me this number. I wanted to say hello. My name is Seabury Quinn.”

“That’s impossible,” I replied. “Seabury Quinn died years ago.”

“Of course he did,” said the man on the phone. “Actually, I’m his son. Your wife thought you would get a kick out of my using my father’s name.”

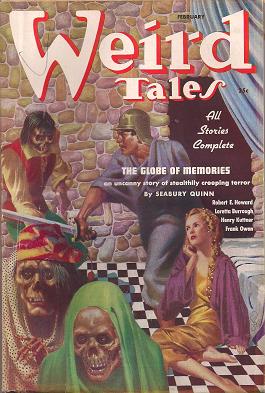

I was astonished. Years before, I had edited a series of six paperbacks featuring Seabury Quinn’s famous occult detective, Jules de Grandin. I had done the editing for Quinn’s second wife. She had never mentioned in our correspondence that Quinn’s son from his first marriage was still alive. Hearing from him was a real thrill. His step-mother had sold me a stack of Weird Tales pulp magazines with Quinn stories in them. I wondered aloud if Quinn’s son had a second stash of pulps? He didn’t, which didn’t bother me much since I was buying a set of the magazine that weekend from Sam Peeples. What Quinn’s son said next set my heart pounding. “I don’t have any of my father’s pulps,” he explained. “But I did hear you’re interested in original art. I own several Weird Tales cover paintings done for my father’s stories.”

Like I said above, it pays to advertise. The younger Quinn had gotten my name from some friends we had in common. He needed some money for a trip he wanted to take to Japan. One of the tidbits of information he had learned about me was my interest in old science fiction and fantasy art and the high prices I was willing to pay for originals. When I got back to Chicago from California, I spoke at length with Quinn’s son. He had two paintings which his father had obtained from the artists who had painted them in the 1930s. But, he was only willing to sell one at the moment. When I learned what that one was, I didn’t complain.

The piece I bought from the younger Quinn was Virgil Finlay’s color cover for the February 1937 issue of Weird Tales, illustrating Seabury Quinn’s story, “The Globe of Memories.” It was Finlay’s first published painting, and was a masterpiece. Mr. Quinn had kept it in perfect shape. I paid a fair price for it. I always credited my ownership of that piece to the joys of self-promotion and advertising one’s collection.

The piece I bought from the younger Quinn was Virgil Finlay’s color cover for the February 1937 issue of Weird Tales, illustrating Seabury Quinn’s story, “The Globe of Memories.” It was Finlay’s first published painting, and was a masterpiece. Mr. Quinn had kept it in perfect shape. I paid a fair price for it. I always credited my ownership of that piece to the joys of self-promotion and advertising one’s collection.

By the way, for the record, the reason Sam Peeples sold off his science fiction collection and his St. John painting to Steve K was that Sam discovered shortly before Steve and EK came to visit that he had cancer and would not live much longer. Sam wanted to sell his collection for a good price so his wife would get the full value for the books and magazines. He survived until the next summer. When he did die, his wife contacted Steve and I again and we bought the remnants of his collection that we had not taken in our initial buy.

I did sell enough of Sam’s collection so that Steve earned back every penny he spent on the books, magazines, and St. John painting. The only other art we found in Sam’s collection was an Edd Cartier calendar pen and ink fantasy drawing which I bought for myself.

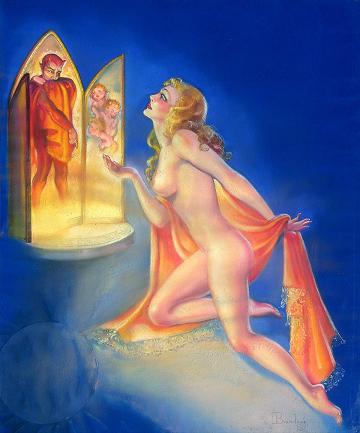

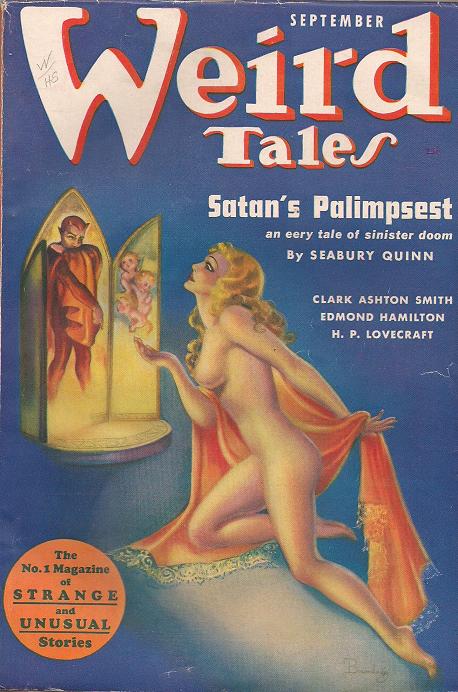

About a year after I bought the Virgil Finlay painting from Seabury Quinn’s son, he called me and asked if I would be interested in buying a Margaret Brundage Weird Tales cover. Of course I was. The original was a stunning piece done entirely in pastel chalks and appeared as the cover for the September 1937 issue of the magazine. It illustrated the Jules de Grandin adventure, “Satan’s Palimpsest.” I paid handsomely for the original but it was worth every penny.

Some time later, my friends Jerry W. and RGC were visiting Forry Ackerman. Afterwards, they stopped in Chicago on their way home and gave me a present they had found at 4e’s home. It was an artist’s proof of that September 1937 Weird Tales cover, autographed by Margaret Brundage. It makes an interesting extra to the original painting. Such are the surprises of collecting in such a small field.

Some time later, my friends Jerry W. and RGC were visiting Forry Ackerman. Afterwards, they stopped in Chicago on their way home and gave me a present they had found at 4e’s home. It was an artist’s proof of that September 1937 Weird Tales cover, autographed by Margaret Brundage. It makes an interesting extra to the original painting. Such are the surprises of collecting in such a small field.

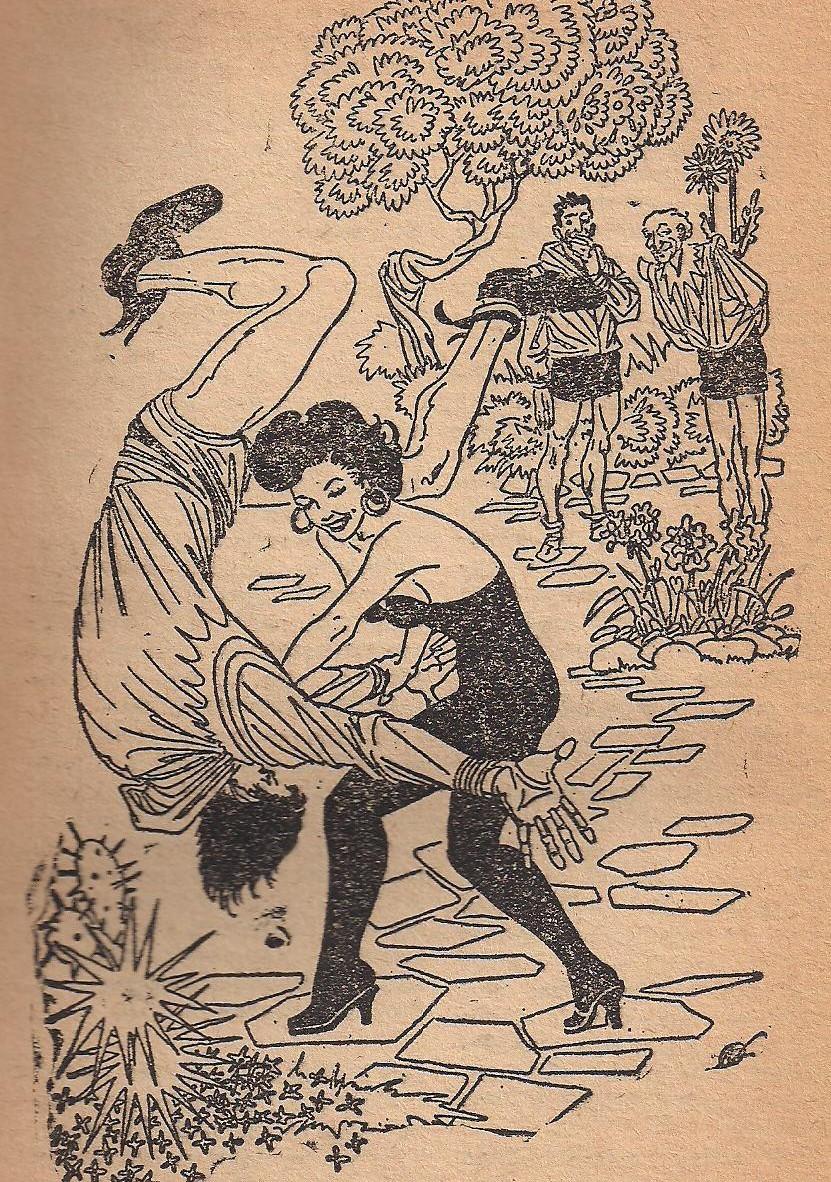

One other small deal made in 1998 stretched coincidence to the breaking point. Fifteen years earlier, I had bought a group of Freas black-and-white interior illustrations from the science fiction magazines. They were all from the 1950s and most were quite nice. Best of the bunch was an illustration for a story titled “The Return from Troy,” written by Russ Winterbotham and published in the Sept. 1947 issue of the digest magazine Science Fiction. The cute Freas illo showed a beautiful girl flipping a young man over her shoulder as two older men watched. The story was lightweight and funny, about equality of the sexes in the future. I had read it years before and the only thing I remembered about it was that I liked the illustration more than the story.

Still, in those days, I actually sold Freas art from time to time. Such original art turned up fairly frequently, so I let originals go if the price was right. As was the case with “Return from Troy,” which I sold to someone in England. It wasn’t until years later when I stopped finding Freas art so often that I realized I had been an idiot to sell a piece I liked so much, especially to someone in England. I wrote to the buyer but when he wrote back it was only to tell me that he had traded the art to someone else. And that he had no memory who that was. So I wrote off that piece forever, a sad lesson learned that if I found something I liked, even if it was only a mild attraction, then I should hang onto it. Because good art, no matter how much I owned, was always hard to find.

Still, in those days, I actually sold Freas art from time to time. Such original art turned up fairly frequently, so I let originals go if the price was right. As was the case with “Return from Troy,” which I sold to someone in England. It wasn’t until years later when I stopped finding Freas art so often that I realized I had been an idiot to sell a piece I liked so much, especially to someone in England. I wrote to the buyer but when he wrote back it was only to tell me that he had traded the art to someone else. And that he had no memory who that was. So I wrote off that piece forever, a sad lesson learned that if I found something I liked, even if it was only a mild attraction, then I should hang onto it. Because good art, no matter how much I owned, was always hard to find.

Flash forward, back to 1998. My friend, Doug E. called me on the phone. He had just completed a deal with a guy in England. The collector had five Freas originals he wanted to sell, and Doug had bought them all. Was I interested in buying any Freas art?

Of course I was, and Doug and his wife, Deb, were coming over to go out to dinner the next day. So he promised to bring the art with him.

An impossible coincidence? I thought so, but the world is a funny place. One of the five illustrations was the black-and-white for “The Return from Troy.” I traded Doug another Freas for the 1957 original. I’ve framed it and the piece hangs on a wall in my bedroom. It serves as a pleasant reminder that even in a field as crazy as collecting original science fiction art, miracles are possible.

~Four~

I turned fifty on August 29, 1996. My birthday fell on the first day of the Los Angeles World Science Fiction convention. I attended that convention, not as a book or art dealer, but as a writer. As mentioned previously, collaborating with my friend, Lois G., a computer programmer, I had begun work on a thriller novel set in the high-tech world of multi-million dollar finance. I attended Worldcon that year to confer with my editors from Random House. Meanwhile, I was also writing a trilogy of novels based on the game Mage, the Ascension, for White Wolf Publishing. This was my second trilogy for White Wolf, who had published my first series, featuring vampires, in 1995. Along with my writing responsibilities, I was also selling Sam Peeples’ collection for my friend, Steve K. I was incredibly busy and had very little free time to look for art. Fortunately, enough people knew about my obsession and came to me without any prompting, offering great pieces for sale.

The best of the best obtained during the next several years was a Lawrence Sterne Stevens cover painting for Famous Fantastic Mysteries for the novel, Phra the Phoenician. The oil painting came from my friend, Norman B., a writer who had written a book about visions of the future found in old science fiction magazines. I had sold Norman a Robert Gibson Jones cover to Amazing which he had used as the cover illustration for his book, so I felt that him selling me the Stevens painting was only fair.

The best of the best obtained during the next several years was a Lawrence Sterne Stevens cover painting for Famous Fantastic Mysteries for the novel, Phra the Phoenician. The oil painting came from my friend, Norman B., a writer who had written a book about visions of the future found in old science fiction magazines. I had sold Norman a Robert Gibson Jones cover to Amazing which he had used as the cover illustration for his book, so I felt that him selling me the Stevens painting was only fair.

In the middle of 1998, the book was judged finished. Lois and I breathed a collective sigh of relief. The novel was scheduled for February 1999 publication. It was the lead Del Rey hardcover release for the winter. The CEO of Random House promised us all sorts of promotion. The print run was set at 100,000 copies. We were scheduled for a 22-city tour across the United States. There was even talk of booking us on morning TV and radio shows.

All of the strain of publicizing the book took a toll on my health. I had undergone major surgery as a teenager, and suddenly that summer I suddenly started bleeding internally. Off I went to the hospital where they discovered several major problems with my health. I was in and out of the hospital for the next six months.

During that time, Random House was bought by the German publisher, Bertelsmann A.G.. In an attempt to show a quick profit, the new owners killed all publicity for their Winter 1999 lineup. All the hard work Lois and I had done on The Termination Node during the past three years was for nothing. Without any publicity, the book was doomed.

I was released from the hospital on a Thursday in early November 1998. I was under strict orders to take it easy and to avoid stress. Easier said than done, when a project I had been working on for three years was dying. I felt emotionally drained. I remembered thinking that nothing could cheer me up. How wrong I was.

The phone rang. Phyllis got it, talked for a minute, then passed the receiver to me. “It’s someone named Jane. She’s from the Church of Scientology. She wants to talk to you about original art.”

How strange. The day I was released from the hospital, feeling depressed, I get a call from the Scientologists regarding art. Actually, not that strange but definitely a major coincidence. During the past year they had been calling fairly frequently. The Church, located in Los Angeles, was building an L. Ron Hubbard museum. They were trying to decorate it with cover paintings of magazines and books in which Hubbard stories had appeared. I owned several such covers and had sold the art to them. Lately, they had been using my name as a reference with other collectors to get them to open their doors. Hearing that I trusted the Scientologists to pay top dollar for their wants worked wonders for the organization. As I picked up the phone from Phyllis, I wondered what they might want.

The person on the other end of the line identified herself as Jane Mc. She was a researcher who reported directly to Tom V., one of the more important people in the Church hierarchy. Jane explained that the Scientologists had just obtained a large collection of original science fiction art. Unfortunately, the artwork was not marked as to who the artist was or where it appeared. They were hoping that I might be able to identify the pieces and maybe even trade some of them with pulp collectors throughout the country.

I must have hesitated answering her. After all, I had just returned from the hospital and was under orders to take it easy.

“No problem,” Jane assured me. “We wouldn’t want to damage one of the most talented persons we know. How much do you usually charge per hour for consulting?”

That was the last question I expected to hear, since I never charged a consulting fee to anyone. But since Jane asked I felt I needed to say something. “$75 an hour,” I told her.

“Very reasonable,” said Jane. “We can pay you that. I’ll see you later tonight.”

“Tonight? Where are you calling from?”

“Los Angeles,” she replied, “I’m in a car heading for the airport right now. I think I arrive at O’Hare around 10 p.m.. I assume there’s a motel or hotel in your town?”

“There’s a Holiday Inn fifteen minutes away,” I said. “We’ll make a reservation for you there for tonight.”

“Sounds good. I’ll see you later.”

So, that was how I was hired by the Church of Scientology to sort through their science fiction art collection, appraise it, and trade as much of it as I could for art illustrating Hubbard stories. It was an improbable and quite remarkable event happening on the day I was released from the hospital. It completely took my mind off the disaster regarding the publication of The Termination Node. Instead of worrying about the book, something I had no control over, I concentrated on making good deals for the Scientologists.

Jane arrived at our house at 11 p.m. that evening. With her were a sheaf of around 45 Xeroxes, some in color, full-size copies of all of the art that was in the collection they had obtained. Originally, she had planned on bringing the actual art with her, but it was just too heavy a package to make it through the airport undamaged. Thus the Xeroxes.

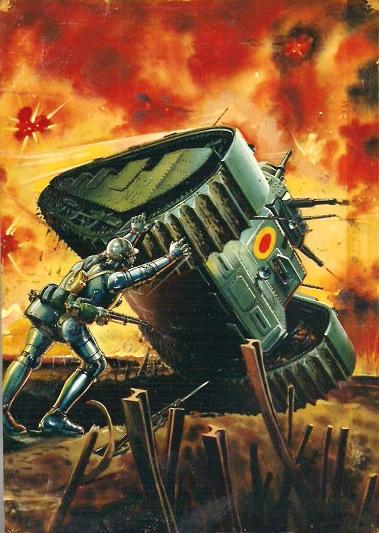

I was thrilled to see what was included in this fabulous collection. I never did learn if they had bought the art or if it had been given to the Church as a gift. Nor did I find out who had assembled the collection, though it seemed that it must have belonged to a west coast fan. Not only had the art turned up in Hollywood where the Church of Scientology was located, but many of the minor pieces were covers for fan magazines that had been published in the 1940s on the west coast.

I spent most of that night identifying artwork that I recognized as being published in the science fiction magazines. Not only do I own every SF publication through 1980, but they are all on display on shelves in my house. Thus, I would identify a piece, search in my magazine indexes for the original publication of the story, then look up that story in the pulp to make sure the artwork was published in that same issue. My work delighted Jane who had expressed despair of ever finding most of the places of publication for the originals.

Around 2 a.m. that night she told me what a spectacular job I was doing. “We got a bargain with you,” she confided to me. “The Church would have paid triple the fee you asked for. Never undervalue yourself.”

It was a lesson that took a long time to sink in. Though it finally did, once I realized how much most professionals charge for their services. I have spent most of my adult life studying and learning the value of original art. My knowledge of prices has made people thousands of dollars. That weekend working with Jane Mc., I obtained numerous L. Ron Hubbard paintings for the Church of Scientology. Without question, my good name made many of those deals possible. I’m sure the Church felt I was worth every penny they paid me. Because I was.

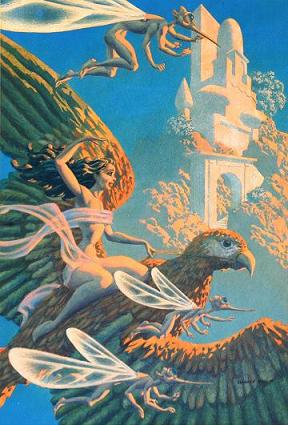

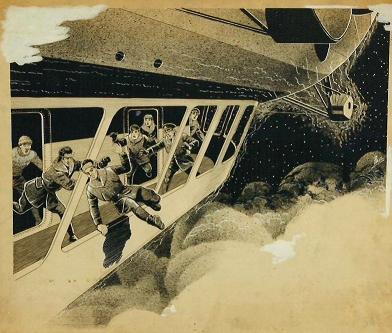

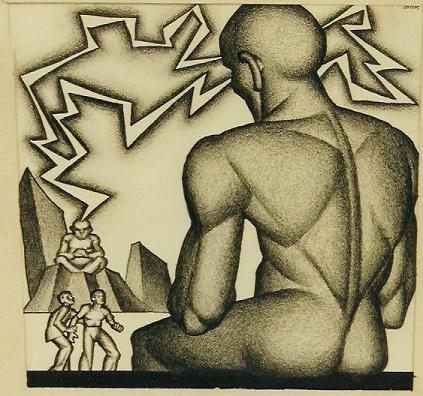

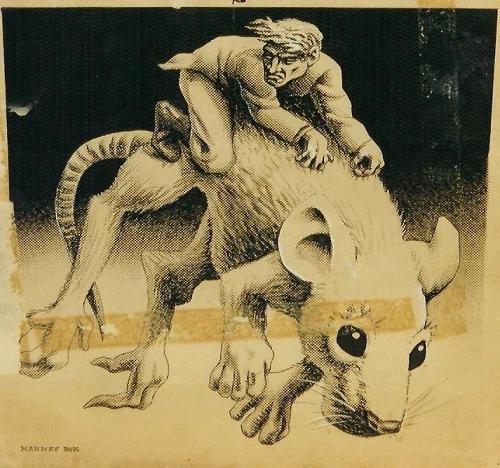

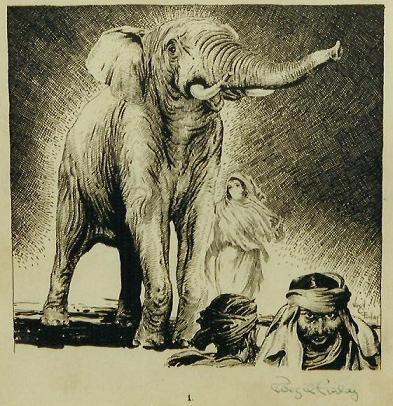

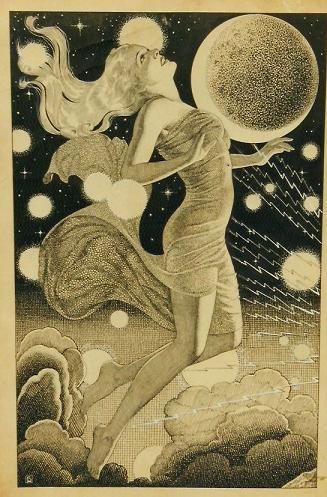

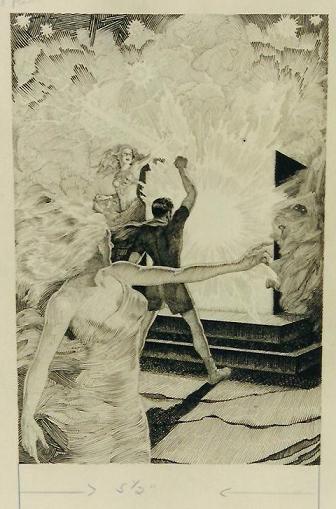

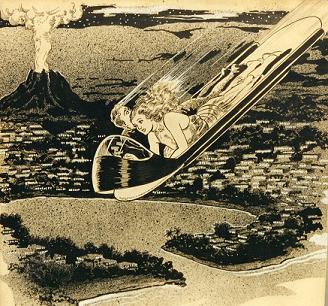

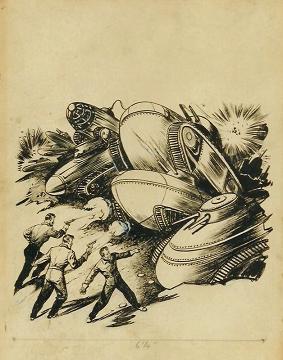

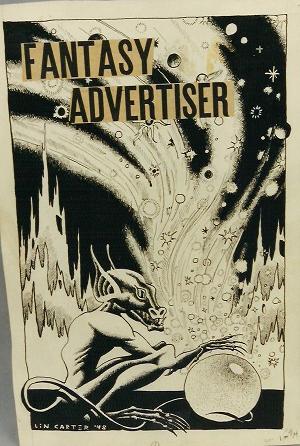

I’ve included pictures of a number of illustrations of art that were in the collection found by the Church of Scientology and traded by me to SF Art collectors throughout the United States. Jane stayed in Oak Forest Thursday night till Sunday afternoon. We made lots of trades for the Church and everyone there was quite pleased with our efforts. Phyllis and I received a standing invitation if we ever were in Hollywood to visit the Church headquarters for a tour of the building and properties owned by the Church. It sounded intriguing.

Saying goodbye to Jane that Sunday afternoon, I felt certain that nothing as unusual could happen in the art field in 1999 to match dealing with the Scientologists late in 1998. Of course, I was soon proven wrong.

The news regarding The Termination Node was all bad. Without explanation, our book tour was cancelled. The big print run was no longer discussed. Our book got no advertisements. The editors who had been pushing it were fired, as was the president of the company. Years later, Lois and I learned that our book was killed because Bertelsmann AG didn’t want to spend any money promoting books bought under the old regime. Thus, all of the books purchased by Random House editors and scheduled for early 1999 release were abandoned.

The Termination Node was published in February 1999, with no publicity and no push. It sold okay, but it was never a best-seller. Lois and I continued to collaborate, but abandoned fiction and instead wrote pop-science non-fiction books like The Computers of Star Trek. I divided my time between writing pop-science books and selling original art. Lois concentrated entirely on her writing career. She rose through the ranks of authors to become a New York Times bestselling writer. Proving that talent will triumph in the end.

(Showcase — Church of Scientology SF art collection)

(Below: Robert Fuqua – Adam Link Fights a War; Frank R. Paul – Beyond the Pole)

(Hannes Bok – Venusian Strategy & Super Science illo)

(Virgil Finlay – Death is an Elephant; Lawrence Stevens – Doorway into Time)

(Lawrence Stevens – The Dark World: Frank R. Paul – Fantastic Adventures illo)

(Leo Morey – Cosmic Stories cover: Russ Manning – fanzine cover)

(Lin Carter – Fantasy Advertiser cover, 1948)

~Next Time~

Column #9

Sam and Darrell, Two Famous Collectors

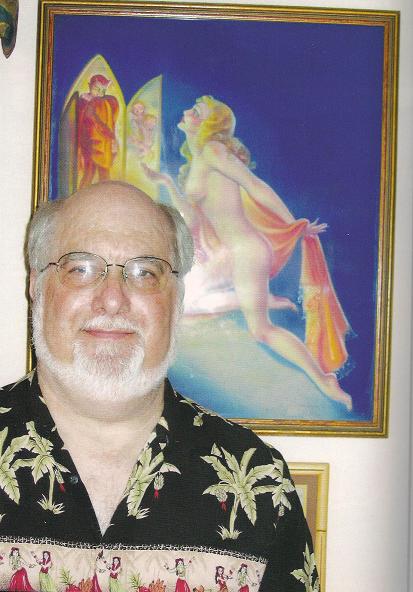

Robert Weinberg is the author of 17 novels, 16 non-fiction books and around a hundred short stories. He’s also edited over 150 anthologies. He owns one of the finest SF/Fantasy original art collections in the world. These days, Bob is busy promoting his new book, Hellfire: Plague of Dragons, done with artist Tom Wood, and serving as editor for Arkham House publishers.

Article and art copyright © 2011 by Robert Weinberg and Tangent Online. All rights reserved