Collecting Fantasy Art #6:

An Art Potpourri

By Robert Weinberg

Copyright © 2011 by Robert Weinberg

A note from the editor:

In this 6th installment of Robert Weinberg’s auto-biographical history of his almost 40 years of Fantasy and Science Fiction art collecting, he relates his roller-coaster ups-and-downs, wheeling and dealing–and ultimate success through luck, friendship, and above-board, ethical gamesmanship–that have led him to acquire priceless, original (rare) works of art from some of the most renowned and beloved artists the fantasy field has ever known.

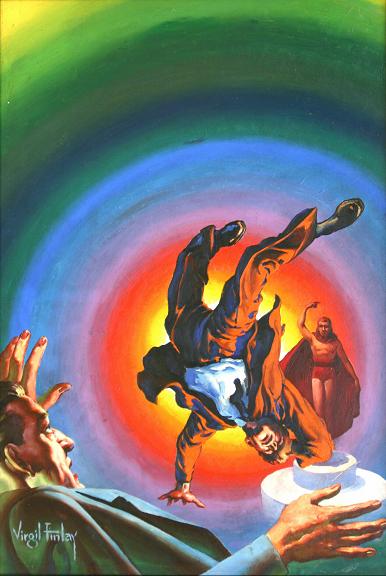

For those “in the know,” (who have become familiar with the artists’ names and a bit of their histories over the years), Robert has included personal insights into his acquiring art from the likes of Stephen Fabian, Earle Bergey, Richard Hescox, Michael Whelan, Peter Andrew Jones, Virgil Finlay, and many others.

As a special feature at the end of Robert’s article, and primarily because he has given us so much of his original art to reproduce which we couldn’t place in the body of the article for aesthetic purposes, we will showcase every single piece of art, in large format, by artist, at the end of the article. We hope you enjoy Robert’s extremely interesting insider look at what it takes to be the (semi-arguably) most successful SF and Fantasy original art collector in the world. Book and magazine art sells the product. Book publishers know it and magazine art departments know it. The artists Robert discusses below (as well as those showcased in previous articles) have been roundly acclaimed, through time (some award-winners, some sadly neglected for their efforts), as the best in the field of fantastic art, each after their own fashion. We hope you enjoy this slice of science fiction and fantasy art history.

~One~

Since I strive to keep this series of articles as accurate as possible, let me start off this column by correcting an obvious mistake I made in the last installment. The name of the wealthy Australian art collector who bought numerous Virgil Finlay originals from Gerry de la Ree was Ron Graham, not Ron Turner. I apologize for making this very obvious mistake.

~Two~

Usually, I start this column with the description of one of my many art adventures and describe how I turned up a spectacular original by someone like Kelly Freas or Hannes Bok. Obviously, I enjoy writing about my deals in the art field and of my triumphs dealing with fans, collectors, and artists. But, I must admit that I’ve experienced a number of setbacks in my near forty year career as an art dealer and art collector. Normally, I don’t like telling those stories, but I do think one in particular is worth recounting. It happened in the early 1980’s and concerns an Edd Cartier painting. Today, I still think of it as the painting that got away.

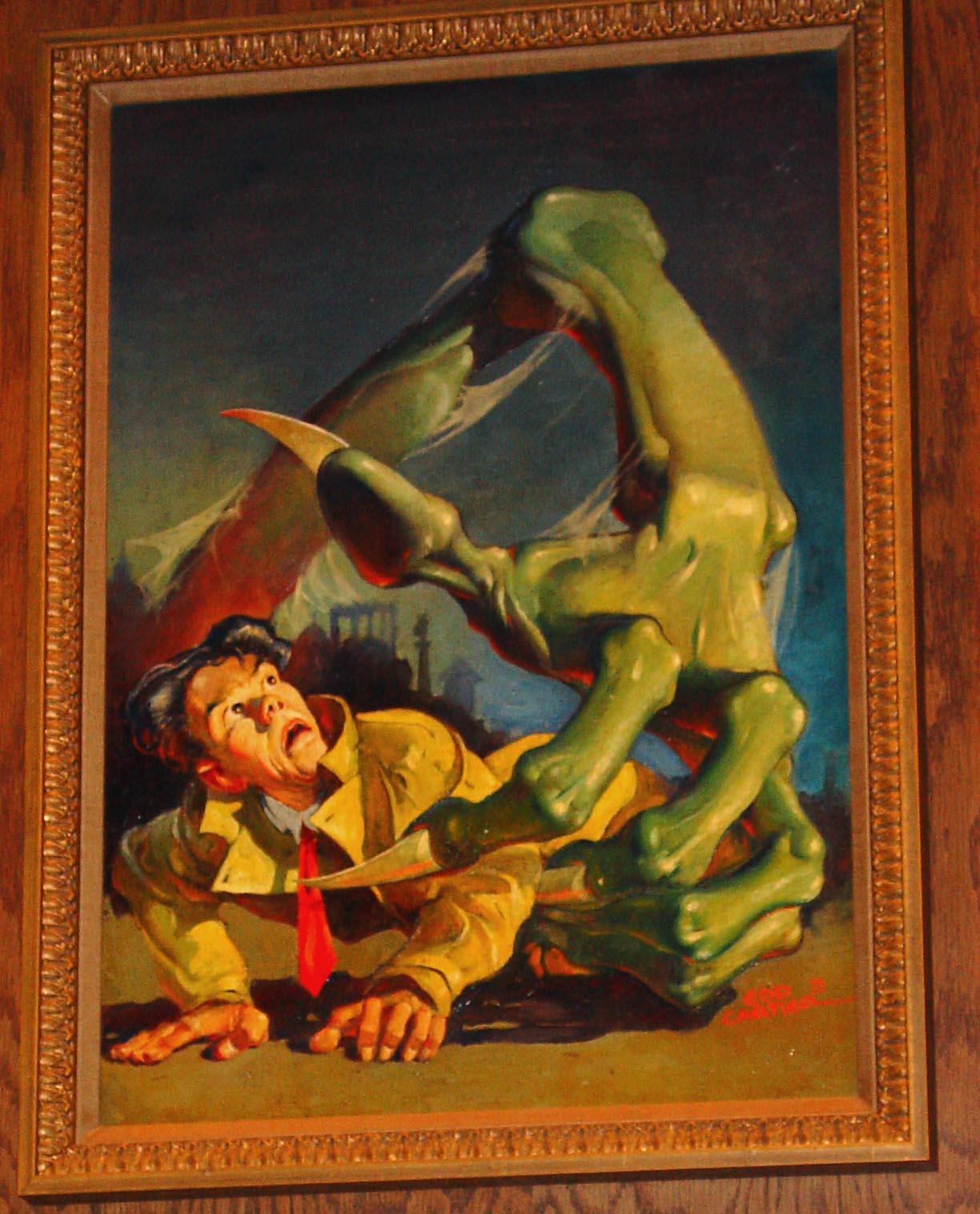

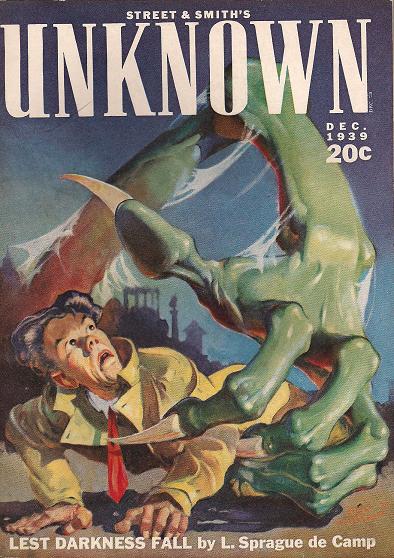

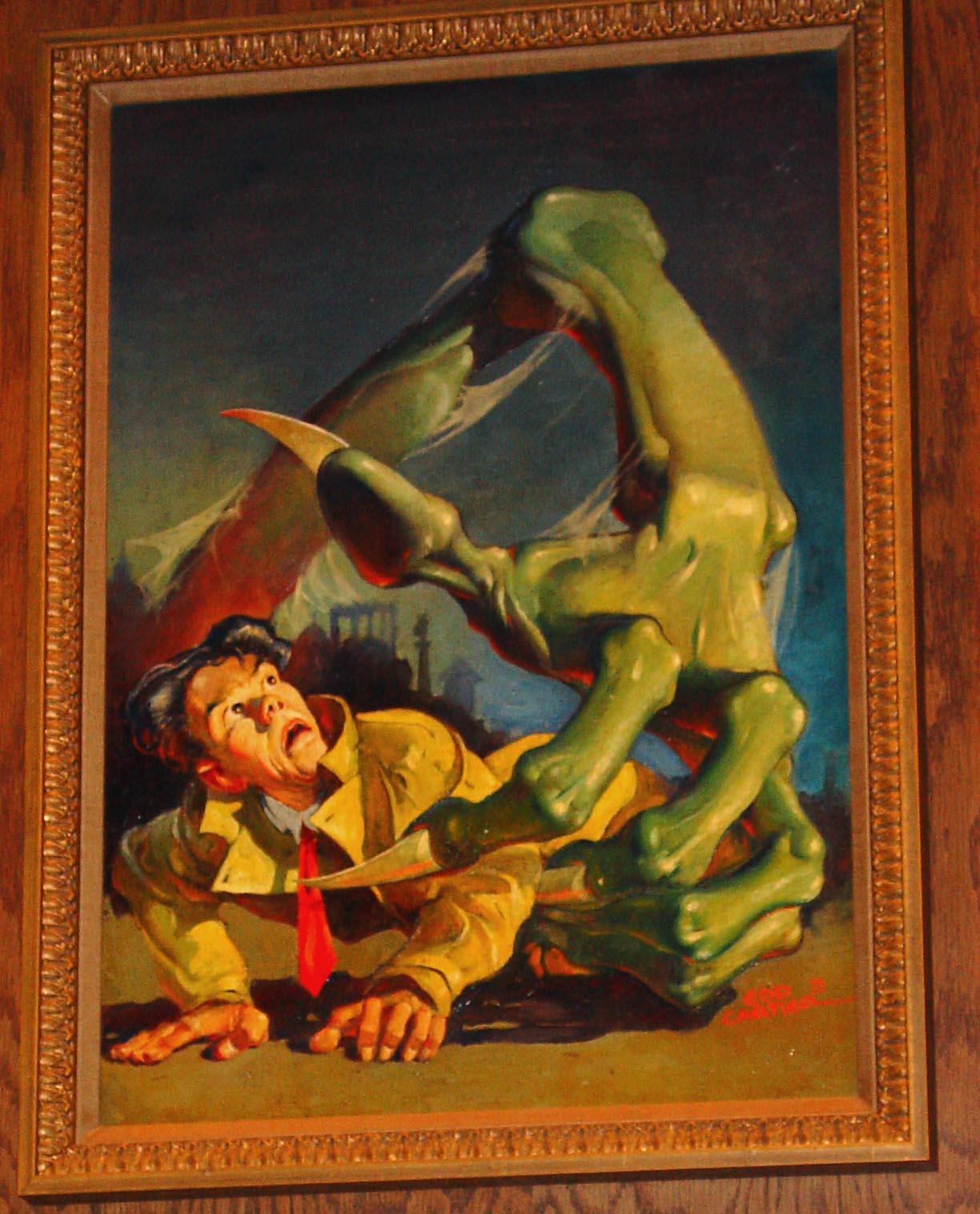

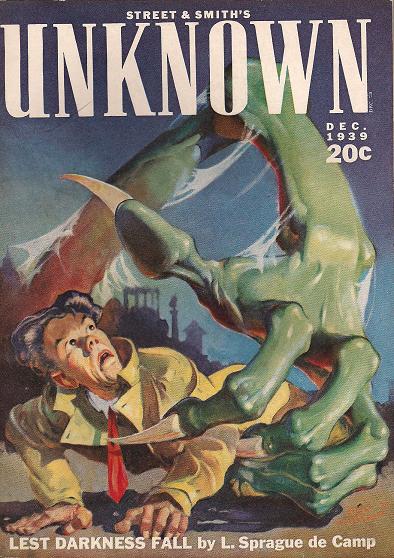

I first saw the piece when I walked into the dealers’ room at PULPcon 12 in Dayton, Ohio in 1983. The painting was standing on a wood easel behind an unrecognized man’s table display. It was large, pulp size, approximately 20 x 30 inches. The colors were bright and unfaded. The illustration was of a man being yanked by a gigantic hand backward in time. The story it illustrated was the original short novel, “Lest Darkness Fall” by L. Sprague de Camp. The painting had appeared on the front cover of Unknown for December 1939. The artist was Edd Cartier, and the painting was one of the few he had ever done for the science fiction magazines. Most likely, it was the only pulp cover painting done by Cartier that had escaped being destroyed when Street & Smith cleared out their warehouse in the late 1950’s.

The painting was terrific and I knew I had to have it. Trembling with excitement, I asked the owner, a bearded man who was not a PULPcon regular, how much he wanted for the painting. “Two thousand dollars,” he told me. “Not a penny less.”

I shook my head. Cartier was relatively forgotten other than to science fiction pulp fans. His black and white art ran a few hundred dollars, rarely more, though it didn’t often turn up. So, I felt certain that no one would pay that ridiculous price. “I’ll give you $1,500 for it,” I said. “That’s what it’s worth. No one will pay $2,000 for it.”

“I’ve had it since the Korean War,” the owner told me. “Now I’m moving from a house to a condo so I don’t have room to hang this up. Still, I know what it’s worth. I want $2,000.”

“You can want that much all day long,” I said, growing somewhat annoyed by the man’s know-it-all attitude. “But it’s only worth $1,500. If you decide to drop the price, my table is over there. Here’s my card.”

“Sure, I’ll drop the price if it doesn’t sell,” said the owner, sounding quite sarcastic. “I’ll take $1,999.99 for the piece. That’s my bargain price.”

“Good luck,” I replied, now feeling quite annoyed. I handed the man my business card. “When you want to sell and are willing to take $1,500 for it, call me. My number is on the card.”

“Don’t hold your breath,” said the owner. “If I don’t sell it here, I plan to attend a bunch of SF Cons. Someone will want it enough to pay my price.”

“At a science fiction convention?” I said, with a laugh. “Nobody will have the least idea who Cartier was. And they won’t pay $2,000 for a pulp painting. Don’t lose my card. You’ll need it.”

The rest of the weekend was spent with me glaring at the stranger’s table with the Cartier painting resting on the easel behind it, and the owner of the painting glaring at me. Neither of us was willing to bend an inch. He was determined to get his price. I was determined to buy the painting for less. It was a stalemate. The weekend passed without either of us saying a word to the other. I won an award, for my contributions to the pulp field. I was pleased. Deals were made and pulps were bought, sold, and traded. The painting remained unsold. I was not surprised.

At convention’s end, I once again approached the painting’s owner. I was willing to compromise and pay $1,750 for the painting. After all, it was one of only a handful of paintings ever done by Cartier, and as far as I knew, might be the only full color Cartier in existence. So I made him my higher offer. And he turned it down!

So much for compromise. I went home angry and annoyed, convinced that the owner of the painting was an idiot and worse. No one would ever pay $2,000 for that painting. He would be stuck with it forever.

Time passed. In casual conversation with L. Sprague de Camp, I learned the history of the painting. At the invitation of the editor of Unknown magazine, he had visited John W. Campbell’s office one day in 1940. Resting on the top of Campbell’s desk was the painting by Edd Cartier used for the cover for de Camp’s story, “Lest Darkness Fall.” The short novel had been the lead story in Unknown for December 1939. Campbell had gotten the painting back from the printer who normally destroyed the art after using it. He thought Sprague would appreciate owning the first cover painting done for one of his stories. Thus, de Camp had taken the painting home with him by the train to Philadelphia.

Time passed. In casual conversation with L. Sprague de Camp, I learned the history of the painting. At the invitation of the editor of Unknown magazine, he had visited John W. Campbell’s office one day in 1940. Resting on the top of Campbell’s desk was the painting by Edd Cartier used for the cover for de Camp’s story, “Lest Darkness Fall.” The short novel had been the lead story in Unknown for December 1939. Campbell had gotten the painting back from the printer who normally destroyed the art after using it. He thought Sprague would appreciate owning the first cover painting done for one of his stories. Thus, de Camp had taken the painting home with him by the train to Philadelphia.

The art had gone not on the wall but in the attic. De Camp appreciated Cartier’s fine work, but he wasn’t a pulp art fan. The painting wasn’t something he or his wife wanted hanging on the walls of his home. Fast forward around a dozen years. It was the early 1950’s and the USA was involved in a “police action” for the United Nations in Korea. A bunch of New York fans thought it would be a nice idea to raise some money to buy science fiction paperbacks for fans who had been drafted to serve overseas. The NY fans asked all the pros in the New York City area to donate stuff to the auction. De Camp brought the Cartier as his contribution. It sold to a fan from Ohio for $40. Needless to say, the fan who bought the painting was the same person who still owned it more than thirty years later.

I was annoyed but it didn’t matter. The painting was gone, the owner was gone, and chances were good that I would never see either of them again. Time passed and neither of them showed up at any of the other Midwest science fiction conventions I attended.

Then came PULPcon 13, held in Cherry Hill, New Jersey in August 1984. I attended the show with my wife, Phyllis, and son, Matthew. We had a good time. Phyllis and Matt spent some time seeing the sights of nearby Philadelphia, while I saw many old friends from my youth when I had lived in New Jersey. The one thing I did not expect to see at the show was the Edd Cartier painting for “Lest Darkness Fall.” But it was there, same as before, with the only thing different, the price. Now, the guy who owned it wanted $2500 for the painting.

I only spoke with him once. He didn’t want to argue with me and I didn’t want to argue with him. He had tried for the past year to sell his painting for $2,000 and had not succeeded. Therefore, he had brought the painting back to PULPcon with the price raised $500. I didn’t understand his reasoning and suspected I never would. I wouldn’t pay him $2,000 for his painting. I definitely would not pay him $2,500 for it.

It wasn’t that I couldn’t afford the painting. My business was quite successful and I had enough money that I could have bought the painting at either price that the owner wanted. I just felt that the piece wasn’t worth the money. At the time, science fiction paintings from the 1930’s and 1940’s were selling for around $1,000 each when they turned up. And the market for such paintings was quite small. Only a few hardcore art collectors were willing to pay that price for old art. Though I loved Cartier art, I just was not going to set a record and pay the obnoxious owner of the painting the price he wanted for the piece. Nor, did I believe, would anyone else.

The convention came and went and the painting wasn’t sold. I returned home to Chicago with my family, convinced that sooner or later the owner of the Cartier painting would get tired of trying to sell it with no luck and accept my offer. I was certain I would get the art at my price. I remained convinced until I heard that two weeks after PULPcon, the owner of the piece had sold it to wealthy California collector, John McLaughlin. He paid the asking price of $2,500.

If that was the end of it, I would have learned my lesson and I would have been properly punished. When something is so rare that it might be unique, like a Cartier painting or a Finlay original from The American Weekly, (patience, dear reader, patience), don’t quibble over the price. Just buy it!

If I had an ounce of sense, when I realized that the owner of the painting wouldn’t bend an inch, I should have swallowed my pride and paid his price. Sure, it would have bruised my ego for a short time. But, having the painting as part of my collection would have healed any wound pretty quick. I felt much, much worse knowing that the piece was owned by John McLaughlin. And that was before he listed it for sale from The Book Sail.

McLaughlin was an odd character who had lots of money that he enjoyed spending on rare collectibles. The heir to a steel fortune, he lived in a stunning home in California and collected original Weird Tales cover paintings by Margaret Brundage. He owned a small book store he called The Book Sail and offered some of his most unusual items for sale at the store. His prices were outrageous because John really didn’t care if he sold anything or not. He liked listing the material in a catalog, as doing so gave him a chance to show off what he owned. The Cartier painting was listed in the Book Sail catalog in 1984 for $6.500.

It didn’t sell for $6,500. After a few years, McLaughlin stopped listing the painting and instead cataloged it as “ask for the price.” Meaning that the price was a lot more than anyone would normally consider paying for such an original.

Years and years passed until one summer, a wealthy friend of mine went to visit John McLaughlin in California after the San Diego Comic convention. This friend was attracted by the Cartier and asked John how much he wanted for the piece. The price, which had doubled then redoubled and then added together the two numbers for a total, from what McLaughlin had originally asked for the original, was mentioned and then agreed upon. The deal was made and the friend returned home with the painting. It sold for approximately 17 ½ times what its owner had originally asked for it. I assume the owner felt bad. I know I did.

But, the saga of “Lest Darkness Fall,” doesn’t end there. A few years ago, my close friend, Doug E. was visiting our mutual friend who bought the Cartier painting and really liked it. Doug spoke to the friend and after some intense bargaining, made a deal for the original. The trade took place soon afterwards. So now, the painting hangs on the wall of Doug’s dining room and I see it every time my wife and I visit his house. It serves as a constant reminder of how stupid and stubborn I was once upon a time, and how, if I had only been a little more reasonable, the painting could have graced the walls of my home. It’s a lesson I won’t ever forget. Ever!

~Three~

I should mention here that I didn’t spend all of my time and money only collecting original artwork from the 1930’s and 1940’s. While I would have been thrilled if I constantly turned up originals by Frank R. Paul, Virgil Finlay, and Edd Cartier, that just didn’t happen. I did find more of my share of art by those artists, mainly because I devoted most of my time and effort searching for art by them. But, despite my best efforts, there were long stretches of time when I didn’t find anything new by them. Oftentimes, many months passed between me finding one Cartier and another. I was somewhat more lucky with Finlay, as I knew his daughter and at the time she had lots of artwork that appealed to me. But, other than one special instance which I discuss below, I couldn’t afford to buy Finlay originals in great quantity. I bought one piece every few months. My bank account couldn’t handle the strain otherwise.

But, just because I didn’t buy artwork from the early days of science fiction, that didn’t mean that I ignored modern science fiction. As a book dealer handling everything new published in the science fiction field, I got to see the covers used for just about everything published in science fiction every month. While the new artists didn’t appeal to me as much as Cartier or Finlay, there were certain artists, particularly painters, whose work I liked quite a bit. And, as an art collector, if I liked an artist’s work on books, I liked it even better on my walls.

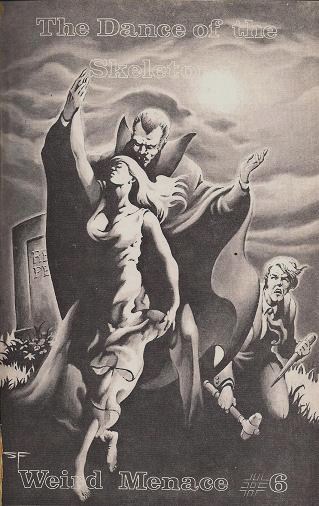

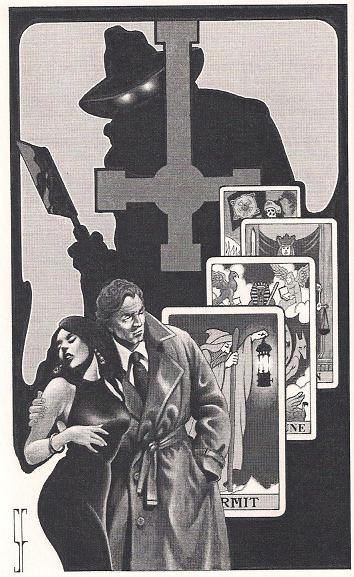

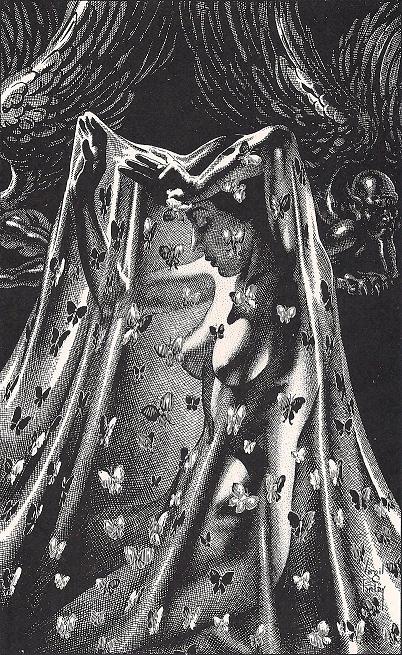

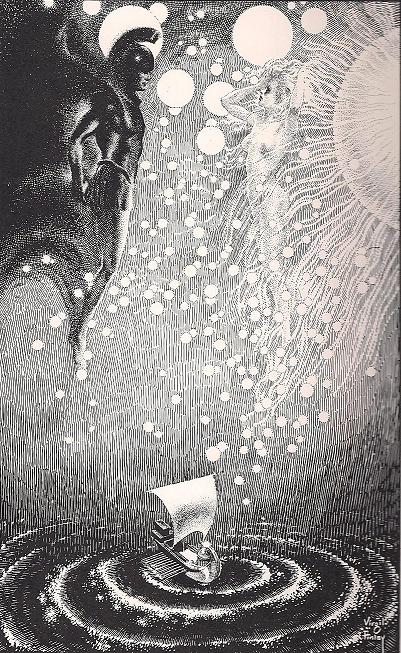

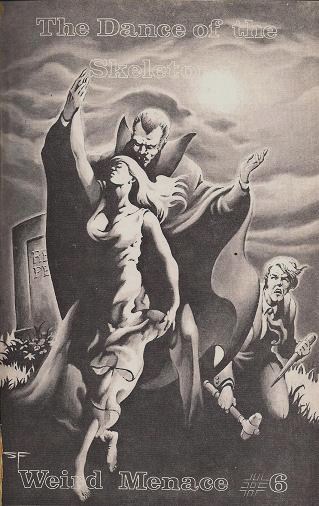

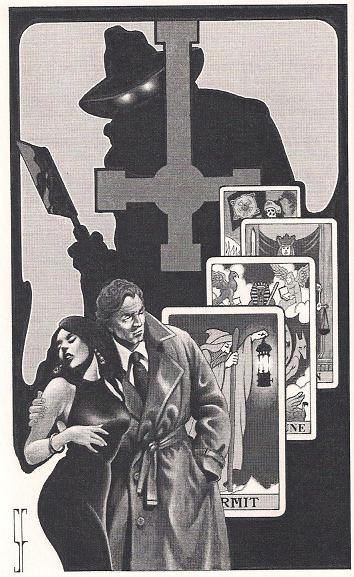

Steve Fabian started out as a fan artist and when he made the switch to full-time professional artist, his rates for originals was still extremely reasonable. The nicest thing about working with Steve is that his asking price was for use of the art, but he also gave a price if you wanted to keep the original. Which many small publishers did. I used black and white illustrations by Steve as covers for a number of small press books I published in the late 1970’s, and in all instances, kept the artwork. When I turned to writing in the late 1980’s and the early 1990’s, my hardcover publishers, usually small press, used Fabian art for the covers for my novels. Steve’s style was a good match for my occult thrillers.

Steve Fabian started out as a fan artist and when he made the switch to full-time professional artist, his rates for originals was still extremely reasonable. The nicest thing about working with Steve is that his asking price was for use of the art, but he also gave a price if you wanted to keep the original. Which many small publishers did. I used black and white illustrations by Steve as covers for a number of small press books I published in the late 1970’s, and in all instances, kept the artwork. When I turned to writing in the late 1980’s and the early 1990’s, my hardcover publishers, usually small press, used Fabian art for the covers for my novels. Steve’s style was a good match for my occult thrillers.

Michael Whelan was probably the most popular artist working in the SF and fantasy fields in the past five decades. His covers for the Elric novels, the Edgar Rice Burroughs Mars novels, and the Foundation trilogy are all considered classics. I liked all of those paintings quite a bit, but though I had the chance at one time or another to buy one painting or another from those series‘, the purchase would have left me unable to buy any other artwork for a year or more. I tried to spend my art money carefully and spread it among numerous pieces. One painting per year might have been a good investment strategy, but it would have taken all the fun out of collecting.

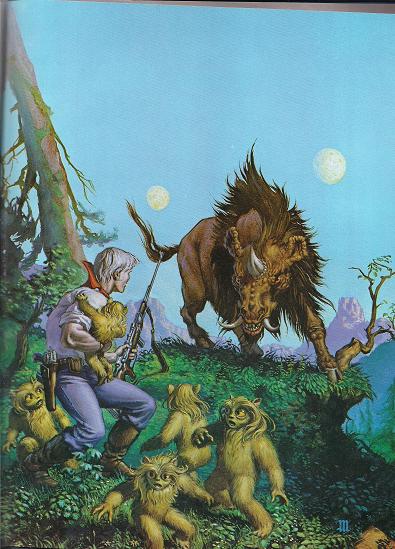

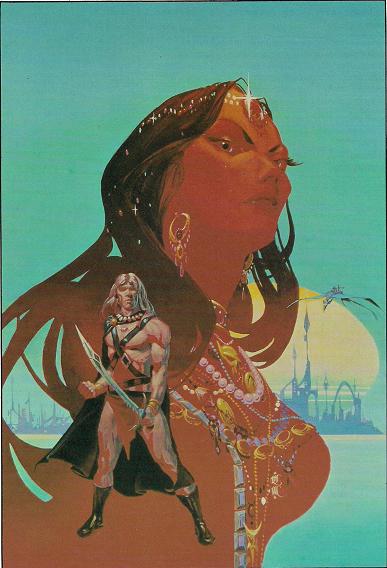

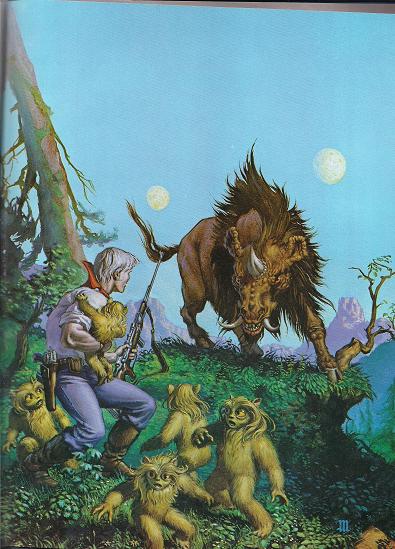

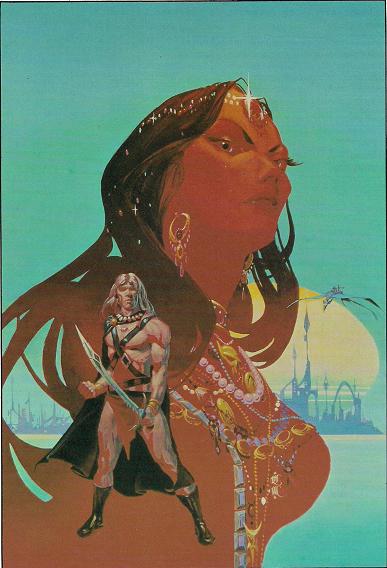

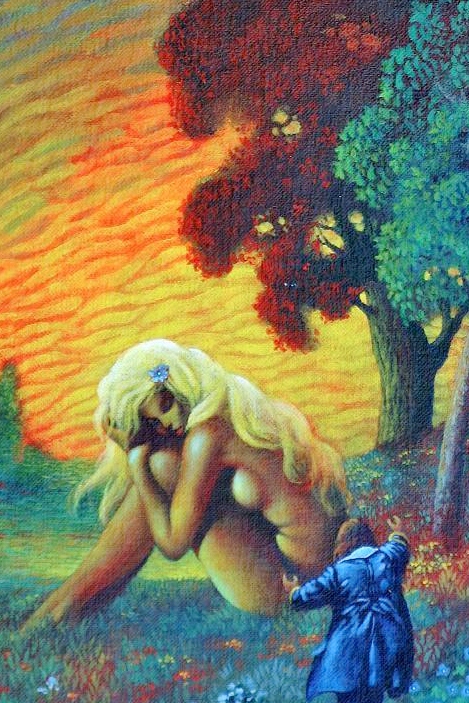

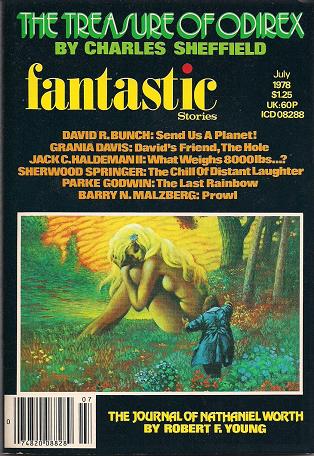

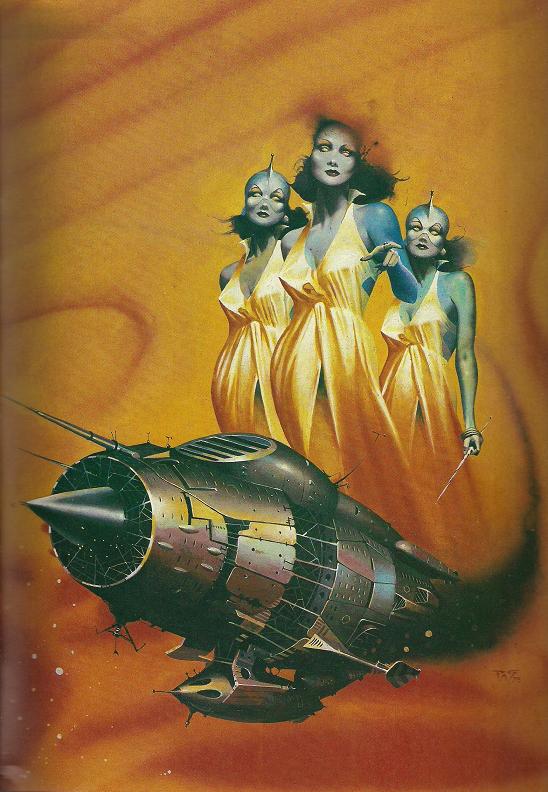

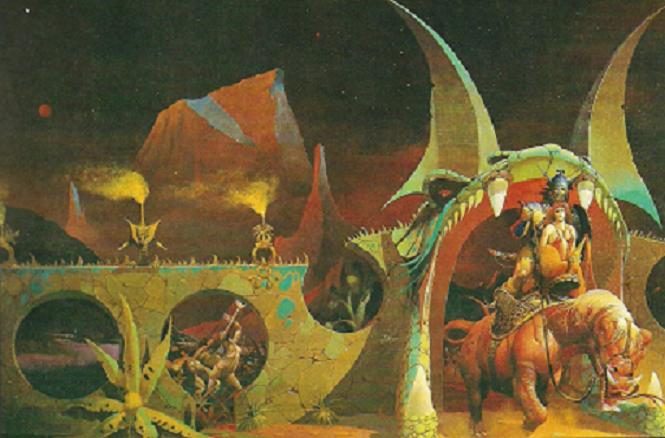

Instead, I managed to buy three Whelan covers in the 1980’s. One was for a Darkover novel by Marion Zimmer Bradley, Red Sun of Danger. The second was for a Little Fuzzy novel, Fuzzy Bones (left). And the third was for a Lin Carter novel published by DAW Books, The Enchantress of World’s End, his first paperback cover (right). I still own the Fuzzy cover, but I’ve let the other two go in trades. Someday I hope to own a Burroughs’ Mars painting or an Elric cover but the chances seem less and less likely.

Instead, I managed to buy three Whelan covers in the 1980’s. One was for a Darkover novel by Marion Zimmer Bradley, Red Sun of Danger. The second was for a Little Fuzzy novel, Fuzzy Bones (left). And the third was for a Lin Carter novel published by DAW Books, The Enchantress of World’s End, his first paperback cover (right). I still own the Fuzzy cover, but I’ve let the other two go in trades. Someday I hope to own a Burroughs’ Mars painting or an Elric cover but the chances seem less and less likely.

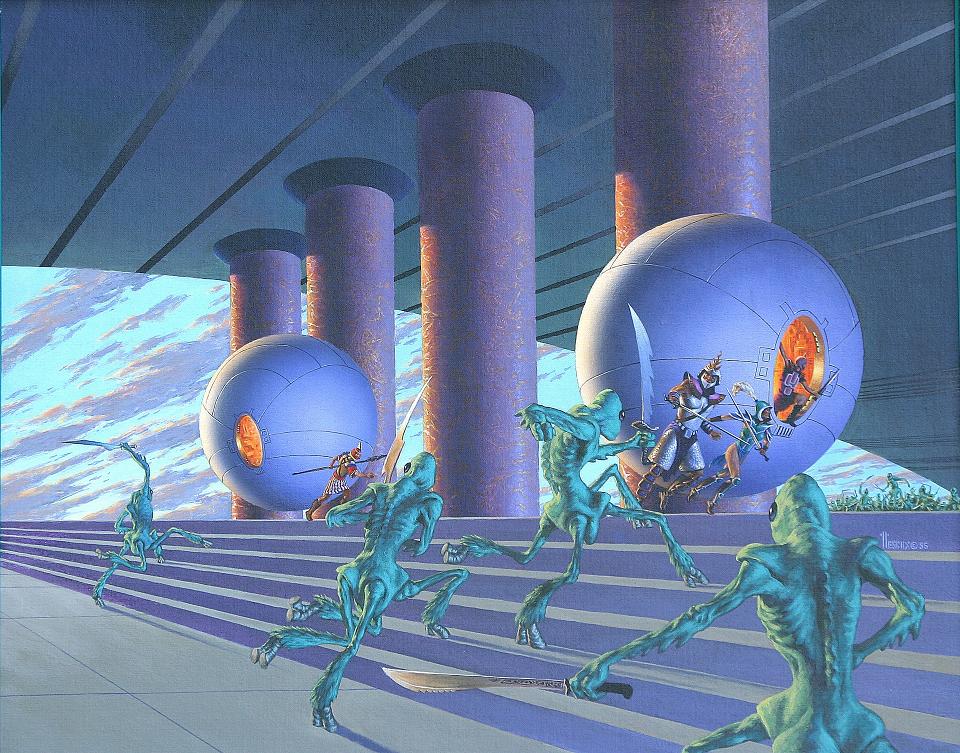

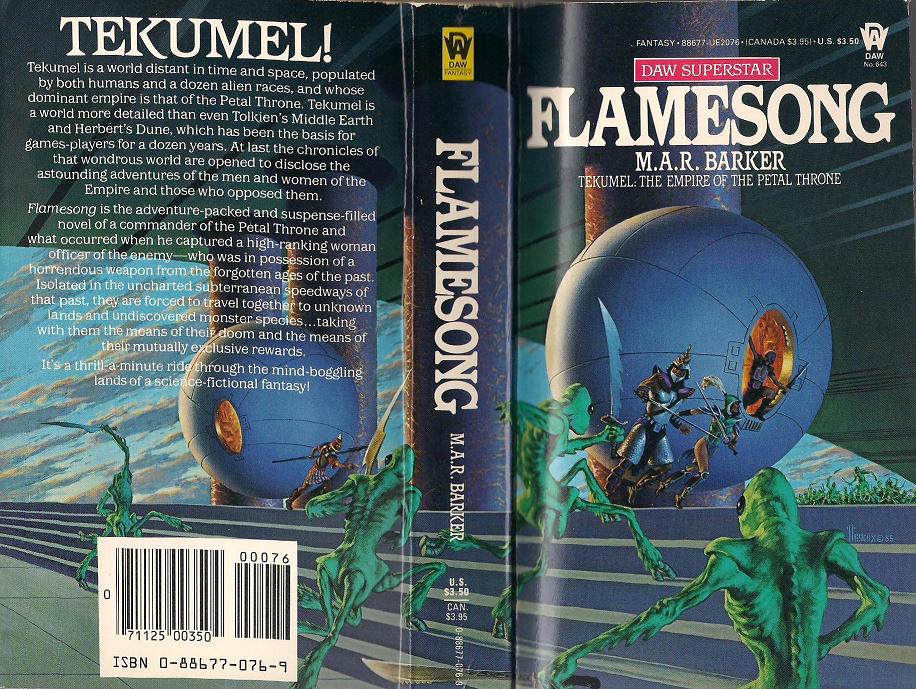

Another artist whose work I always liked was Richard Hescox. His early work for DAW Books was spectacular. I wrote to the Society of Illustrators and asked if they had a contact address for him. They did. He lived in California. At the time, Victor D. was my partner in the art business and he lived in Phoenix, Arizona, only a few hours away from Hescox’s home. I gave him Hescox’s address, but made it clear that if Victor discovered Hescox had art for sale, I claimed the cover painting for Flamesong, a DAW paperback from a year before {see intro art top right of this article, and full image plus book cover following article, ed.}. Hescox, it turned out, did have paintings for sale, and Victor bought several of them for his own collection. Flamesong was available and I got that. I still own it.

I found James Gurney, the artist who became famous for Dinotopia, pretty much the same way. In that situation, I contacted him directly, about six months before Dinotopia was published. He had a number of very nice science fiction paintings for sale at reasonable prices. I bought one. If I had known he was going to be famous with Dinotopia, I probably would have bought several others. But I can’t see the future nor do I want to.

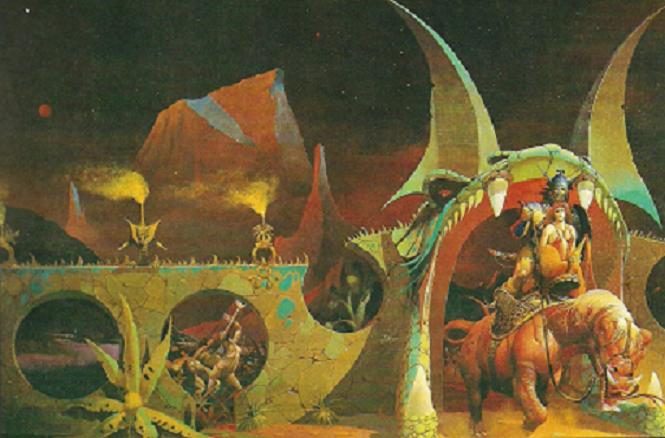

Along with handling every American science fiction and fantasy paperback published each month, my book business also handled every British SF and fantasy book published each month. I wasn’t a big fan of Jim Burns or Chris Foss, who were extremely popular during the 1980’s and considered to be the leading British SF artists. Instead, I liked the artwork of Peter Andrew Jones (from Solar Wind, at right). Paper Tiger Books in England had published a collection of his art titled Solar Wind, and I found an address in it to write to Peter. I sent him a letter and asked if he had any of his art for sale, particularly pieces in Solar Wind? He wrote back and told me that some of the paintings in the book were sold but that he still had most, and that he could give me a good price on them. He was right; his prices were about half those of what comparable American artists charged. So I bought a half-dozen paintings from him. Afterwards, I passed on his address to Victor D. and a number of other U.S. art collectors who I thought would appreciate buying some of Peter’s work. He sold dozens of paintings to collectors in the USA. Proving, in my eyes, that there’s always a market for good art.

Along with handling every American science fiction and fantasy paperback published each month, my book business also handled every British SF and fantasy book published each month. I wasn’t a big fan of Jim Burns or Chris Foss, who were extremely popular during the 1980’s and considered to be the leading British SF artists. Instead, I liked the artwork of Peter Andrew Jones (from Solar Wind, at right). Paper Tiger Books in England had published a collection of his art titled Solar Wind, and I found an address in it to write to Peter. I sent him a letter and asked if he had any of his art for sale, particularly pieces in Solar Wind? He wrote back and told me that some of the paintings in the book were sold but that he still had most, and that he could give me a good price on them. He was right; his prices were about half those of what comparable American artists charged. So I bought a half-dozen paintings from him. Afterwards, I passed on his address to Victor D. and a number of other U.S. art collectors who I thought would appreciate buying some of Peter’s work. He sold dozens of paintings to collectors in the USA. Proving, in my eyes, that there’s always a market for good art.

~Four~

I wasn’t sure what to expect from the 1990’s when it came to original art. After nearly twenty years of collecting art, I had a feeling that it was about time for my luck to run out. It seemed absolutely impossible for me to stumble onto one incredible deal after another.

In the 1970’s, I had been involved with selling art from the Galaxy chain of science fiction magazines as well as handling hundreds of paperback cover originals used by Ace Books. I also bought the art collection of Earl K, one of the premier art fans of the 1950’s. Add to all that, I contacted H.R. van Dongen and bought a bunch of his original cover paintings done for Astounding SF. All in all, my first decade of collecting art had been pretty spectacular.

The 1980’s hadn’t been that bad either. It was at the beginning of that decade that I began corresponding with Martin Greenberg, the original owner of Gnome Press. Over the course of several years, I bought a number of classic paintings used as dust jackets for famous Gnome hardcover volumes. Dealing with Marty G. had been an exciting experience.

Not, however, as exciting as dealing with Roger from Florida, who had over a thousand framed paintings hidden in a store front in a tiny strip mall in the Sunshine State. Roger had bought all the paintings from the Pyramid Books paperback warehouse and was selling them framed as office decorations. I bought sixty pieces from him, with most of the art for resale, but I got several spectacular pieces for my own collection.

Did I forget to mention that an ad I ran in Publisher’s Weekly nabbed a group of twenty oil paintings by famous pulp artist, Fred Blakeslee? The pieces were air war pulp covers from the 1930’s and 1940’s and I turned them over during the course of the decade for a very nice profit. That was surely one of the best financial deals I made in my years selling original art.

Then, there were the deals I made with Richard Hescox, James Gurney, Stephen Fabian, and Peter Andrew Jones for new artwork at reasonable prices. I still have art by all of them hanging on the walls of my house.

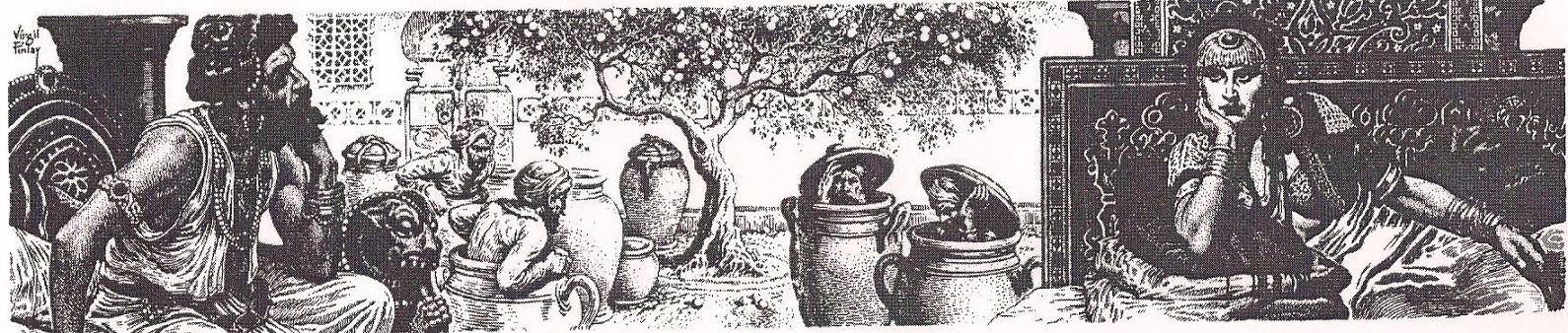

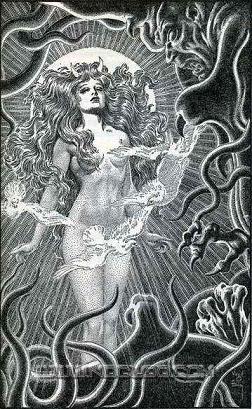

One of the best deals I made as a collector was buying a number of spectacular original black and white illustrations from Lail Finlay, the only daughter of famed SF and fantasy artist Virgil Finlay. Lail, it turned out, had inherited many of her father’s favorite illustrations that he had kept separate from those he had offered for sale. While she wasn’t anxious to let the pieces go, she was constantly expanding her business and selling the art helped her finance the transition. I was lucky enough to buy most of what Lail offered for sale. Luck in that situation meant that I was the first person to realize what Lail considered fair prices for her father’s work and that I paid her those prices without argument.

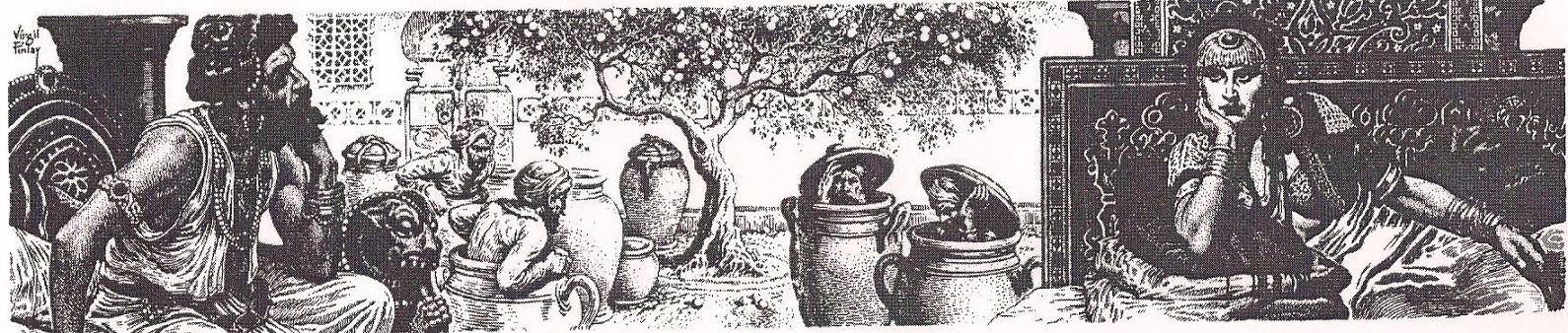

Take, for example, a stunning piece Finlay did illustrating The Arabian Nights for the Doubleday Book Club. His detailed illustration featured forty thieves hiding in oil jars, beautiful Scheherazade telling their story, and the wealthy king listening to her every word. The art was stunning. When Lail put it up for bid, she got two offers for it. One was from an old timer, who offered her $100 for the piece. The other was from me, offering her ten times as much. My offer she considered reasonable. The other made her laugh.

Still, Lail was in no rush to sell the originals that remained. Every few months, she offered me one or two more. After nearly twenty years of incredible luck, I was resigned to a slow down period of collecting. I had started with nothing in 1972 and had assembled one of the best collections of historical science fiction art in the world. I owned originals by Frank R. Paul, Hannes Bok, Edd Cartier, Harold McCauley, Malcolm Smith, Ed Emsh, Kelly Freas, Ed Valigursky, and Virgil Finlay. The walls of my home were covered by originals.

In the meantime…

The nineties was a time for making new friends.

In the early 1990’s, I met two collectors who became important figures in my life. They were both fairly new to science fiction, having both been major figures in the comic book collecting field. Each of them was interested in assembling a major science fiction and fantasy collection and had already started doing so when they met me. As I was one of the major dealers in rare books and science fiction pulp magazines, they were extremely interested in what I had to offer. Plus, they used me to make contacts in the science fiction field that they otherwise would never have been able to make. As the decade advanced, the three of us became close friends and our deals and trades grew more and more elaborate. A number of my very best art trades were made with one or the other of these two friends.

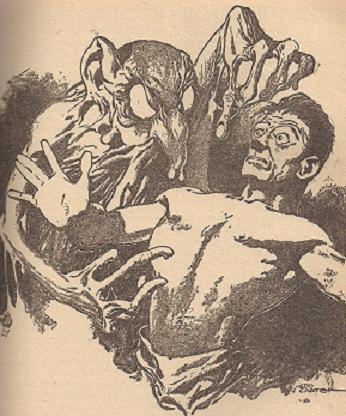

I first met Jerry W. through comic art dealer, Tom H. who I knew through a number of art deals we had made in the 1980’s. Oddly enough, the most interesting bargain I ever bought from Tom involved a piece of art by Edd Cartier.

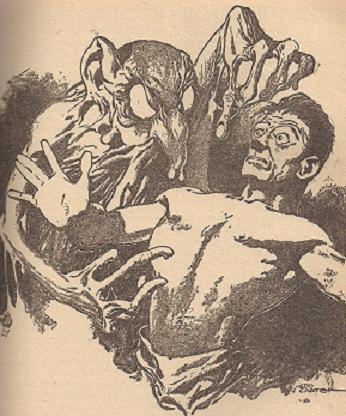

Once, in particular, at a Chicago Comic Con, Tom arrived at the show carrying an Edd Cartier original in his hands. I immediately recognized the piece. It was the lead illustration for the story, “Vault of the Beast” by A.E. van Vogt from Astounding SF in 1940 (illo at left). The adventure, with a plot that revolved around the ultimate prime number, was one of my all-time favorite SF stories dealing with mathematics and I really wanted that illustration. However, Tom wanted $2,000 for it, and the art was yellowed and cracked with age and had pin-holes in the corners. Those marks told me the art had come from 4e Ackerman. Ackerman loved SF Art but didn’t believe in getting it framed. Instead, he posted it on the walls of his home using thumb tacks in the corners of the illustrations. I really wanted that illo, but I refused to pay $2,000 for it. (I guess I didn’t learn anything after all from my adventure with the lost painting, another Cartier!) I kept close watch on the piece all weekend and no one expressed the least interest in the Cartier. Finally, the last day of the convention, Tom brought the piece over to me and asked, “A thousand?”

Once, in particular, at a Chicago Comic Con, Tom arrived at the show carrying an Edd Cartier original in his hands. I immediately recognized the piece. It was the lead illustration for the story, “Vault of the Beast” by A.E. van Vogt from Astounding SF in 1940 (illo at left). The adventure, with a plot that revolved around the ultimate prime number, was one of my all-time favorite SF stories dealing with mathematics and I really wanted that illustration. However, Tom wanted $2,000 for it, and the art was yellowed and cracked with age and had pin-holes in the corners. Those marks told me the art had come from 4e Ackerman. Ackerman loved SF Art but didn’t believe in getting it framed. Instead, he posted it on the walls of his home using thumb tacks in the corners of the illustrations. I really wanted that illo, but I refused to pay $2,000 for it. (I guess I didn’t learn anything after all from my adventure with the lost painting, another Cartier!) I kept close watch on the piece all weekend and no one expressed the least interest in the Cartier. Finally, the last day of the convention, Tom brought the piece over to me and asked, “A thousand?”

“Done,” I answered, paid him his money, and took possession of the Cartier. It sits, restored and framed under glass, right past the monitor of my computer. I felt very satisfied with myself, sticking to what was a fair price for the illo. Of course, if another art collector had been at the show and scooped up the Cartier at Tom’s original price, I would have felt like an idiot. Dealing in art, you either felt like a king or a fool. There was no middle.

Jerry was well known among comic book collectors, having published one of the finest EC fanzines of the 1960’s through 1980’s. He had become famous with the average fan when he opened the first comic book store in Harvard Square, called Million Year Picnic in 1974. Jerry had long since sold his interest in the comic book store. Now, he was working as a consultant for Sotheby’s Auction House in New York. Talking with him, I soon learned that he was a dedicated science fiction fan as much as a comic book collector, and that his favorite author was, not surprisingly, Ray Bradbury, the author of the story, “The Million Year Picnic.”

Jerry and I became good friends. At the time, he wasn’t really very interested in science fiction art. He felt that it was an expensive detour from his main interest, hard cover books. Jerry, in the early 1990’s, was dedicated to assembling a world class science fiction book collection. He pursued rare books with a passion, and left artwork for his friends to collect. Jerry planned that once he had his book collection in order, he would then, and only then, turn his attention to art. At least, that was his plan. Until I wrecked it.

Meanwhile, in the early 1990’s, Jerry introduced me to his good friend and fellow comic book and art collector, RGC from Texas. RGC was well known as a collector of EC Comics original art, as he had bought most of the cover art for the EC science fiction line when it had been auctioned off by Russ Cochran. RGC had money and was willing to spend it on things he wanted. His favorite books were The Lord of the Rings trilogy and he liked artwork by Frank Frazetta, Ed Emsh, Kelly Freas, and Virgil Finlay. When he moved into the science fiction art field, he quickly made his mark. Everyone knew immediately that a major new player had joined the fray.

At the time RGC entered the science fiction art field, a good Finlay black and white illustration sold for around $1,000. A spectacular piece might sell for double that, though there were bargains to be found. A nice Finlay painting, one that had served as a pulp magazine cover or cover art for a young adult science fiction novel hard cover book, usually sold in the neighborhood of $5,000. At the time, I remember selling several stunning Finlay pulp magazine covers for $5,000 each. I also sold several interior illustrations for $750 per original. Two Hannes Bok black and whites cost me $1,000 for the pair, and I bought several very attractive Kelly Freas originals for $100 each. Prices were all over the map and no one was certain how much anything was worth. Remember, my adventure with John McLaughlin and the Book Sail had taken place approximately 8 years earlier than these sales, and the price he paid for the Cartier painting made all of these pieces look like incredible bargains.

The art world was changing fast. Robert Lesser was buying old science fiction originals by Frank R. Paul and paying top dollar for pieces from the 1930’s. Lesser was slowly divesting Forry Ackerman of his collection of Paul original covers from Wonder Stories, paying $13,000 for each painting. Lesser was financed by the sale of his Disney memorabilia collection for hundreds of thousands of dollars. He obtained paintings from old-timers who swore they would never sell the original art in their collections by overwhelming them with money. Lesser paid $25,000 for St. John paintings and he had no trouble finding Burroughs fans who, at that price, were willing to make a deal.

RGC might not have used Lesser’s precise tactics as a model, but he did follow the same strategy. He flew up to New Jersey (in his own plane) and went to visit Gerry de la Ree in Saddle River. RGC offered Gerry the price of a Finlay painting for each of the five black and white illustrations done for the Borden Memorial hard cover edition of The Ship of Ishtar. The price of five paintings to pay for five black and white originals. Gerry couldn’t say no. The Finlay black and whites for The Ship of Ishtar might have been his finest set of Finlay illustrations, but he had plenty of others nearly as good. And he couldn’t say no to that much money.

~Five~

I had been buying art by Virgil Finlay from Lail Finlay slowly but steadily since the late 1980’s. When 1992 arrived, I had no doubt that I would continue to do so for the next few years or until I ran out of money. Lail seemed to have an inexhaustible supply of excellent Finlays, and fortunately, my book business was doing well enough that I had the necessary money to pay for them.

That situation changed unexpectedly one afternoon in the summer of 1992. Lail owned a business in a strip mall and business was booming. She needed to expand but she was crowded in by successful stores on either side of her location. Nor was there any other open space in the mall bigger than the store she already occupied. So, she was resigned to staying put. Until, totally unexpected, on a Wednesday, Lail came to work and discovered that the store on her left had suddenly gone out of business. The space was empty. A quick phone call to the strip mall owners and a deal was made. If Lail could come up with the money for the additional rent; for knocking out the wall between the two stores; for the necessary redecorating; and misc. other bills, the empty store was hers. All she needed, she figured after some quick calculations, was $25,000. Which was a good deal more than she had in savings.

“How much more?” I asked when talking with her late that night on the phone.

“All of it,” she admitted. “All $25,000.”

The reason for Lail’s call was simple. She needed $25,000 in a hurry. The only person she knew who might have that much money was me. She figured I might be willing to make a deal. She would supply me with a lot of art, paintings as well as black and white illustrations, if I would send her $25,000. By now, she knew my taste, and she felt certain she could pick pieces that would make me happy. Plus, I could specify certain pieces if I could remember them from lists she had sent. Coming up with $25,000 worth of art that I wanted by my favorite artist wouldn’t be difficult. It was just a lot of art to buy at one time. And I had to make my decision that night, because she needed the money as soon as possible.

I hesitated, but just for an instant. I couldn’t pass on the opportunity to buy a bunch of Finlay cover paintings and black and white interior illustrations at a bargain price. I went to the bank the next morning and got Lail a check for $25,000. I sent it to her express mail later in the afternoon.

Art started arriving the next day.

The color art included several science fiction pulp magazine covers, several paperback covers, and several dust jacket paintings for Andre Norton novels published by World Books. The black and whites included a number of Weird Tales originals from the 1930’s and the 1950’s. It was a treasure trove of original art. The value of my Finlay collection doubled overnight. However, the deal left me without a penny to buy original art. Since that usually meant Lail Finlay, I didn’t worry much. Lail wasn’t planning to sell any art for a few months.

But, Gerry de la Ree was.

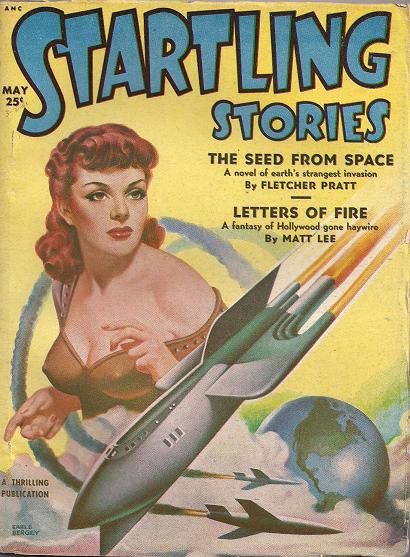

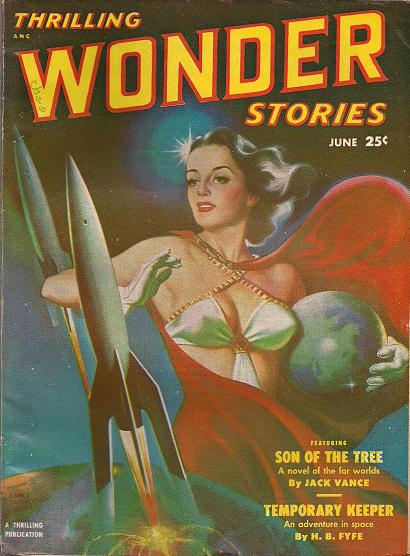

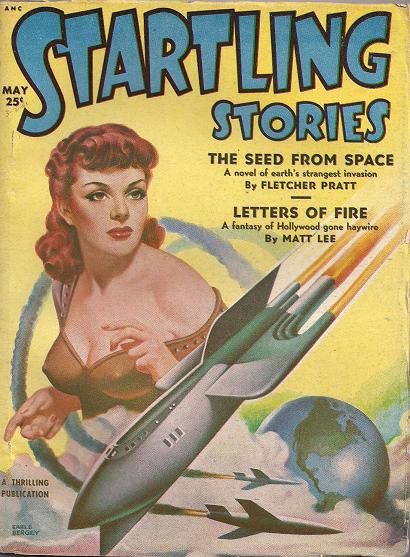

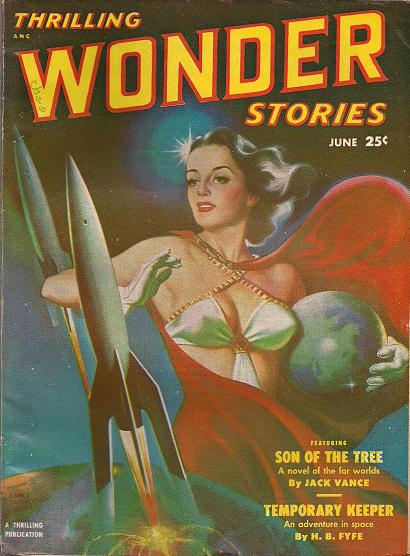

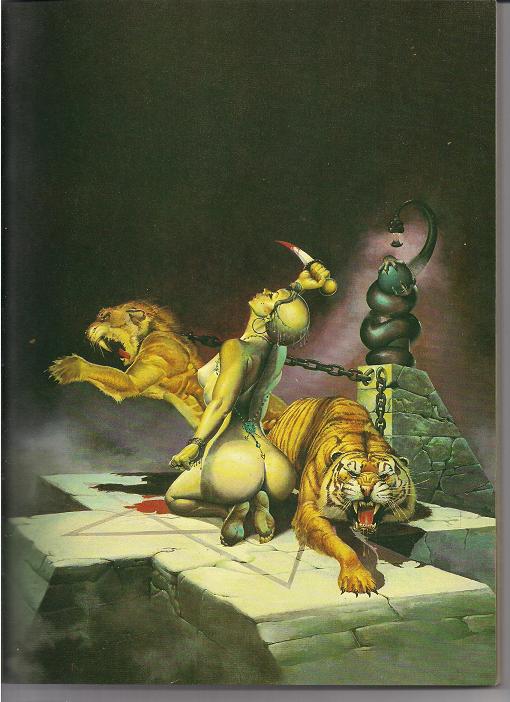

Gerry owned two paintings by famous pulp artist, Earle Bergey. It was one of his famous stories, how he had complained to Sam Mines, the editor of Startling Stories, that there were no Bergey paintings available for collectors to buy. How Mines had told him to get into his car and had driven him to a warehouse filled with art from the Better Publications magazines, and had told Gerry to pick two. And that was how Gerry obtained a pair of Earle Bergey originals for his collection. It was a great story and it might even have been true. No one knew.

Gerry owned two paintings by famous pulp artist, Earle Bergey. It was one of his famous stories, how he had complained to Sam Mines, the editor of Startling Stories, that there were no Bergey paintings available for collectors to buy. How Mines had told him to get into his car and had driven him to a warehouse filled with art from the Better Publications magazines, and had told Gerry to pick two. And that was how Gerry obtained a pair of Earle Bergey originals for his collection. It was a great story and it might even have been true. No one knew.

It didn’t matter how Gerry had obtained the two paintings. All I knew was that I wanted one of them. Either one of them. I told Gerry that every time I visited him, and that was fairly often when I lived on the East Coast. Enough times that whenever anyone else asked if the two paintings would ever be available for sale or trade, Gerry would tell them, “They’re reserved for Weinberg.” It was a well-known fact that when Gerry let the two pieces go, they were going to be mine. Or so I thought.

One weekend that summer, I got a call from the San Diego Comic Book Convention. It was one of my close friends in the comic book field who also bought science fiction art from me. “Didn’t you tell me that Gerry de la Ree promised he would sell you his two Bergey paintings?” the friend asked.

“That he did,” I answered, a sinking feeling in my stomach.

“Well, that’s one promise you can forget about,” said my friend. “The two paintings are here at Joe Mn.’s table. He has both of them for sale.”

Joe Mn. was a comic book dealer who served as a consultant for Christie’s Auction House in New York. Just like Jerry W., he assembled sales of collectible items for the auction house to sell. I had no idea that he had somehow persuaded Gerry to put stuff in his auctions.

The two paintings sold at the San Diego convention, bought by science fiction art collectors who were attending the con, hoping to find some good artwork to purchase. I felt bad losing the two originals, but not too bad since I was broke and never would have been able to afford them. Still, I was annoyed that Gerry had broken his promise. So a few days after the end of the convention, I called Gerry and asked what was up. How come he had given the paintings to Joe Mn.? Why hadn’t he called me and offered them to me first?

Gerry wasn’t the least bit apologetic. Joe Mn. lived in the same town as Gerry and had called him one day and came to visit. While he had been there, he had convinced Gerry that he could get him good prices for any of his artwork that he wanted to sell. So, Gerry decided to give him the two Earle Bergey paintings to see what he could do with them. Joe had sold the two for $5,000 each so Gerry was happy. I should have attended San Diego that year. End of story.

I wasn’t happy but there wasn’t much I could do about it. There was no deal in writing regarding the two paintings.

Late that year, Gerry de la Ree died. A diabetic, he had been in poor health for years. I suppose he had sold those two paintings because he realized he was dying and wanted the money for his wife, Helen. Maybe. Twenty years later, it doesn’t really matter.

~Six~

Early in 1993, RGC called me on the phone. He was going to be in Chicago on a trip and wondered if he could stop by? I was fine with that. I enjoyed having company and I especially enjoyed when other art collectors came by. Talk often turned to trades and I was always interested in hearing what other collectors were willing to let go.

“Maybe we could discuss a trade?” I suggested.

“Exactly what I had in mind,” he replied with a laugh. “I know you’re interested in Finlay. Who else appeals to you?”

“I like Roy Krenkel,” I said, hoping but without much hope. I knew from previous conversations that RGC had two Krenkel Ace Burroughs cover paintings. I couldn’t imagine he would consider trading either one of them.

“Maybe,” said RGC. “Let me think about it.”

Hanging up the phone, I couldn’t help but wonder what RGC might want for those two Krenkel originals. I knew he had paid a pretty high price for them and suspected he would want to make a profit on any deal for either piece. While I was willing to trade multiple pieces for one spectacular piece, I had no idea what RGC would consider a fair price for the Krenkels. At least I didn’t have a long time to brood over the possible deals. RGC was due that weekend.

Come Saturday and RGC pulled up to my house in a rented car right around noon. He had two large portfolios which he brought into my house. After devouring a quick lunch, we got down to the business of trading. From the first portfolio, RGC pulled out the five Finlay originals done for the Borden Memorial hard cover volume of The Ship of Ishtar. Without question, they were among the finest Finlay illustrations ever done. “I promised Gerry if I ever traded these, I would only do so as a set,” said RGC. “And I would want you to pledge to do the same. If we make a deal for them, you would never let them go unless they were as a set. They belong that way and should stay that way.”

“I agree 100%,” I said. “Though I’m not sure I have enough stuff to offer you for the set of five pieces.”

“I agree 100%,” I said. “Though I’m not sure I have enough stuff to offer you for the set of five pieces.”

“Actually, I have more than five,” said RGC. It turned out that he had bought a number of other spectacular pieces from Gerry when he had visited him. He had brought some of those along as well.

“Before my eyes burn out, show me what’s in the other portfolio,” I said. If there had been a half-dozen Finlay paintings in that portfolio, I would not have blinked.

No Finlay’s. Instead, there were two Roy Krenkel Edgar Rice Burroughs Ace paperback covers. One cover was for the short novel, Out of Time’s Abyss. The other painting was for the story collection, The Wizard of Venus. Both were stunning. And both were for trade.

The big question that I needed answered right away was what was RGC interested in getting for his treasures? I didn’t have any Krenkel paintings for trade. And I refused to trade any of my good Finlay originals, even if it was to get better Finlay pieces. I wanted my collection to expand, and trading pieces up but not out wasn’t the way to manage that.

I didn’t have to worry. RGC was anxious to expand his science fiction art collection. He appreciated Finlay and Bok and other artists from the 1940’s, but he was more interested in obtaining paintings from the 1950’s and 1960’s, when he first started reading SF. He wanted paintings from Freas and Emsh and Valigursky and Richard Powers. He knew how much money he had into all of the Ship of Ishtar originals and the two Krenkel paintings. He would give me generous amounts for Freas and Emsh and Valigursky originals, nearly as much as Finlay paintings had been selling for in recent years. As long as he could select a large number of good paintings by those particular artists.

I couldn’t refuse. Not with five of the very best Finlay originals ever done sitting on my living room floor. Not unless I was losing my mind. Nor could I pass on obtaining two Roy Krenkel paintings for Edgar Rice Burroughs paperbacks published by Ace Books. A dozen of my best Freas, Emsh and Valigursky paintings exited my house that afternoon. I felt terrible letting them go. Some of them numbered among the finest paintings ever done by those artists. I had fought hard to obtain a number of those pieces. But, I had to make that trade. I had to. I would have been a fool not to.

It was a crazy way to start 1993. It was only a preview of things to come.

Artist Showcase

Virgil Finlay

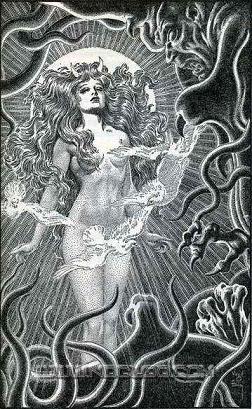

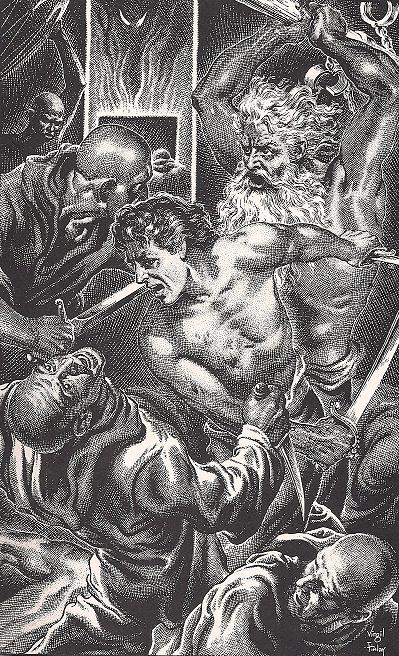

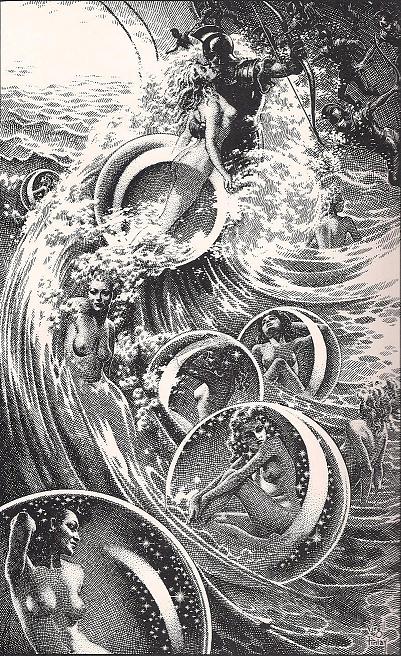

(Above from The Arabian Nights; below, 5 from A. Merritt’s The Ship of Ishtar, and others)

Edd Cartier

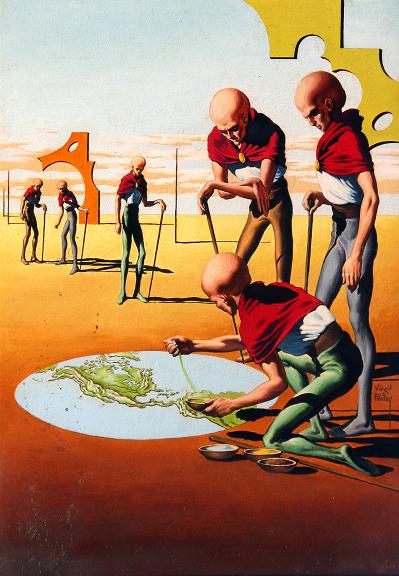

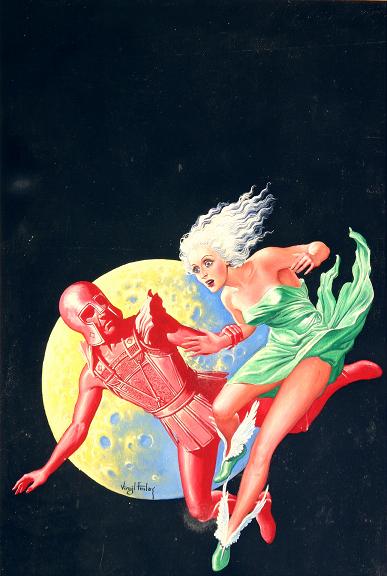

Earle Bergey

Richard Hescox

Michael Whelan

Stephen Fabian

Peter Andrew Jones

~Next Time~

Column #7

The Tale of Two Women: Susan and Betsy and a lot of spectacular art.

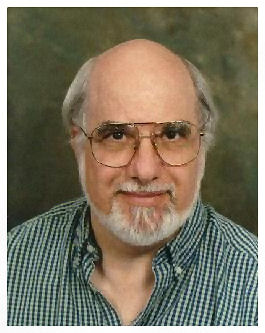

Robert Weinberg is the author of 17 novels, 16 non-fiction books and around a hundred short stories. He’s also edited over 150 anthologies. He owns one of the finest SF/Fantasy original art collections in the world. These days, Bob is busy promoting his new book, Hellfire: Plague of Dragons, done with artist Tom Wood, and serving as editor for Arkham House publishers.

Article text and art copyright © 2011 by Robert Weinberg and Tangent Online. Introductory text © 2011 Dave Truesdale and Tangent Online.

All Rights Reserved for all material herein (art, text, and photos).