Collecting Fantasy Art # 4:

Art Mania!

by

Copyright © 2011 by Robert Weinberg

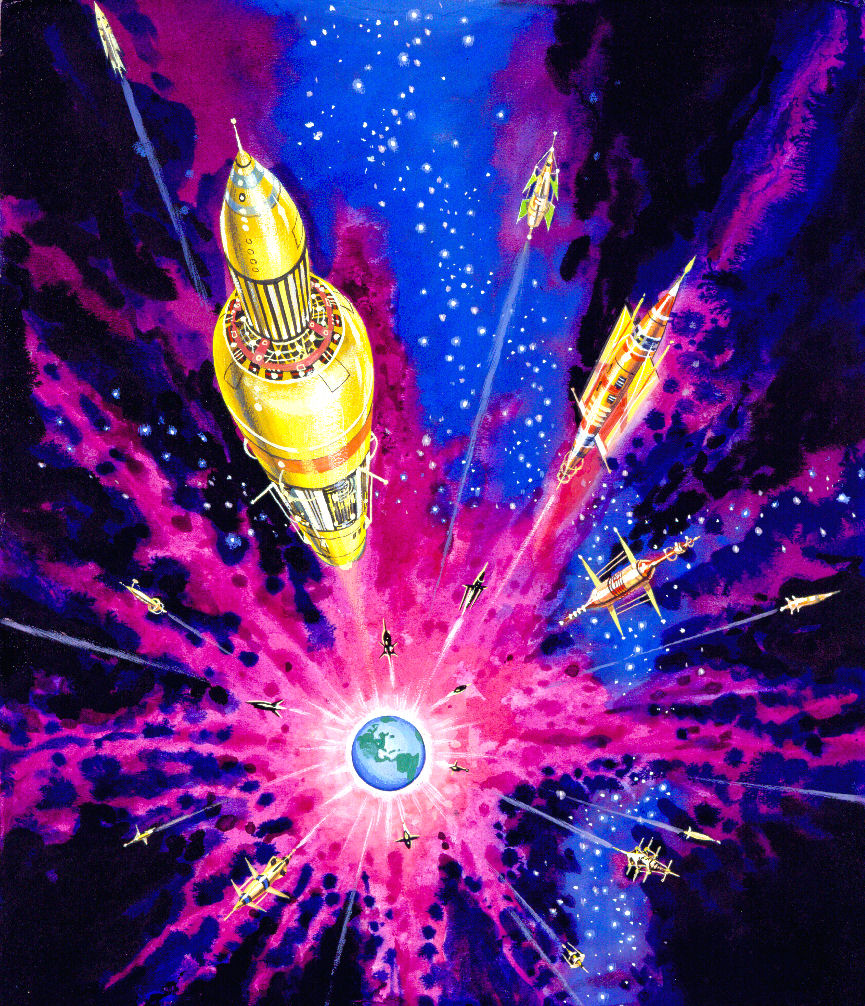

Image: “The Great Explosion” by Emsh

Robert Weinberg continues his personal look back at the earliest years of his almost four decades of collecting science-fiction and fantasy art with this fourth installment, called “Art Mania!” Once the collecting bug had bitten him, Bob ended up buying more art than even he had thought possible, and from some unlikely sources. Surprises abounded for the serious fantasy art collector, and Bob tells about some deals he wouldn’t have thought possible. Again we thank Bob for providing this continuing historical perspective (which has all the earmarks of a book in the making somewhere down the road), and also for providing select pieces from his personal collection to enhance his fascinating narrative.

One

Last column I described the thrill of buying two original paintings from Margaret Brundage, the famous cover artist for Weird Tales magazine. I also discussed my dealings with Martin Greenberg, the founder of Gnome Press, and how I bought a number of Gnome Press originals from him. Plus, there were other deals, like buying a bunch of 1950s Astounding covers from Henry Richard van Dongen. The 1970s and early 1980s were an amazing time to be collecting original art. I had a hard time keeping up with the deals. That’s why I have even more fabulous buys to discuss, before we move onward into the late 1980s. It was collecting at its most frantic pace. It was Art Mania!

In the first article in this series, I mentioned how one of the first paintings I bought was the cover to the first installment of “The Door into Summer” written by Heinlein, and painted by Kelly Freas. Art Dobin sold it to me for $90. Well, at the World SF Convention in Kansas City in 1976, a collector named Al from Texas brought along the cover painting to the third and final installment of the serial. It was by Freas but nothing terribly exciting. Still, it was the cover for a serial and I owned one of the other covers. Might I not someday be able to locate the cover for the second installment of the serial and maybe buy it? It seemed possible, and the thought of owning all three covers used to illustrate a Robert Heinlein novel appealed to me. Unfortunately, in talking with Al, he mentioned that he knew who owned the cover for the second installment of the serial. The painting was actually in Chicago. It belonged to Alex E. one of Chicago’s best known art collectors and a hardcore Freas fan. I knew that getting the cover for that second installment from Alex would be impossible, so I abandoned any thought of buying the cover for the third part of the serial. That was a bad mistake. I learned an important collecting lesson years later that reflected my decision. “Never, never, give up hope. Even the most outlandish and unbelievable deals in the world sometimes take place.” I bought a bunch of 1950s Freas black and whites from Al, but I passed on the painting. Needless to say, years later, when I wanted to buy it, the piece was long sold.

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, I was involved in numerous deals involving dozens, and sometimes even hundreds of paintings. Because I don’t have a photographic memory nor do I want this series to continue for a thousand installments, I won’t be covering all of the deals I made for one piece of art here, and another piece of art, there. Let it just be stated that during those years, I spent a reasonable amount of money advertising to buy original art by such artists as Virgil Finlay, Edd Cartier, Hannes Bok, Kelly Freas, and Ed Emsh. I found a few pieces by these master artists, but not a huge number. Cartier’s work, I soon learned, was quite rare and most of Bok’s work was owned by collectors who weren’t anxious to let any of it go. I don’t want to imply that Virgil Finlay’s work was much more common than pieces by the other two men, but I did have somewhat better luck finding it. That was due partly to the fact that Finlay had done such a huge amount of illustration for the pulps and science fiction magazines. His total output consisted of more than three thousand originals, and art by him had been sold at every Worldcon dating back to the first such event in 1939. Finlay’s art was out there, in the hands of collectors, big and small. Tracking it down became my passion.

Howard Funk was a science fiction fan and collector who I had corresponded with when I lived in Chicago. I finally met him when I moved to his hometown, Chicago, in 1972. Howard was an elderly man who had been a fan way back in the 1930s. He had started the first science fiction club in Chicago and had attended the Chicago World SF Convention in 1940. When Howard learned of my sudden interest in collecting art, he told me that he owned two Frank R. Paul paintings that had been done for Fantastic Adventures magazine back in the early 1940s. These paintings had been given to Howard by Ray Palmer, the editor of the magazine, and Howard had promised them to his nephew when he died. However, Howard did have a small but very detailed illustration by Virgil Finlay that he had gotten somewhere but couldn’t remember what it was from. One day while we were talking about old science fiction magazines, Howard gave me the Finlay as an addition to my growing collection. It was my first Finlay and was a great piece. The only problem with it was that I didn’t recognize it and had no idea where it might have been published.

Pardon me if I break continuity, but I will resume my stories about the 1970s shortly. Jump forward twenty five years, to the late 1990s. By now, I’ve assembled a terrific collection of Virgil Finlay art. It is one of the best collections of Finlay art in the world. Every piece is identified and framed… except for that one small piece from Howard Funk. I still hadn’t identified it, and until I did, I refused to put it in a frame or hang it on a wall. But I was getting pretty tired of not knowing where it was from.

Pardon me if I break continuity, but I will resume my stories about the 1970s shortly. Jump forward twenty five years, to the late 1990s. By now, I’ve assembled a terrific collection of Virgil Finlay art. It is one of the best collections of Finlay art in the world. Every piece is identified and framed… except for that one small piece from Howard Funk. I still hadn’t identified it, and until I did, I refused to put it in a frame or hang it on a wall. But I was getting pretty tired of not knowing where it was from.

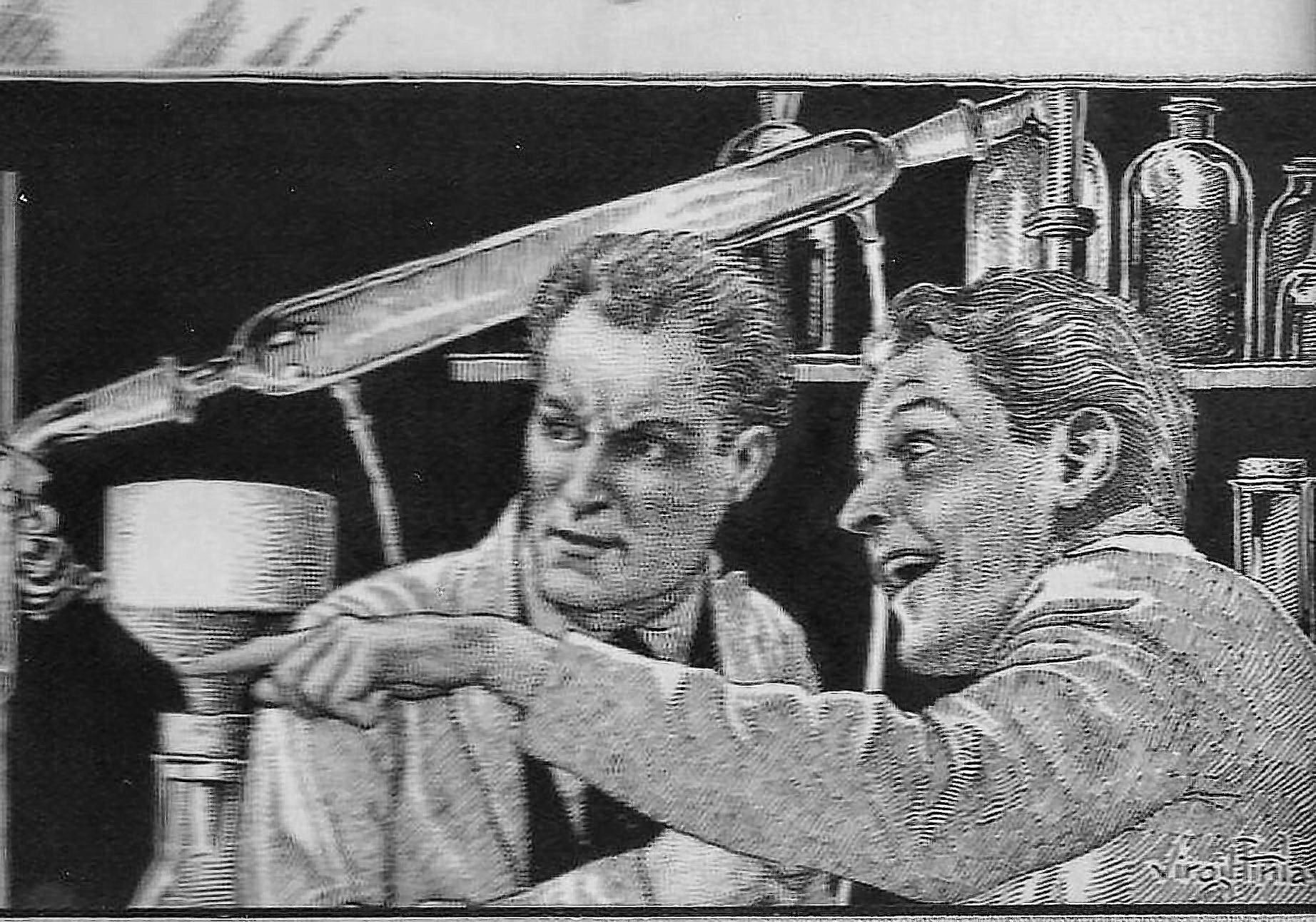

Image: Test Tube Girl (Part #1) by Finlay

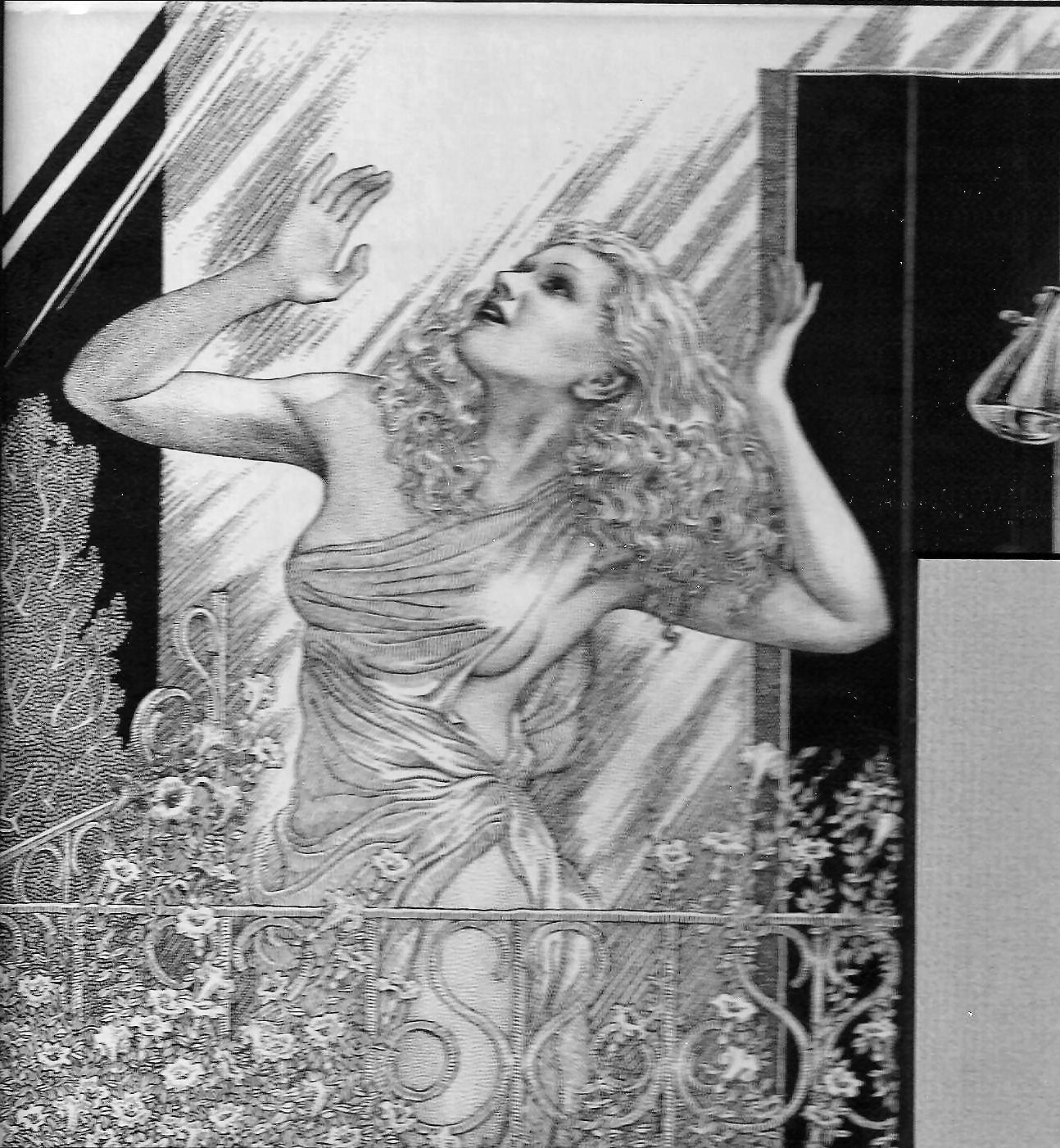

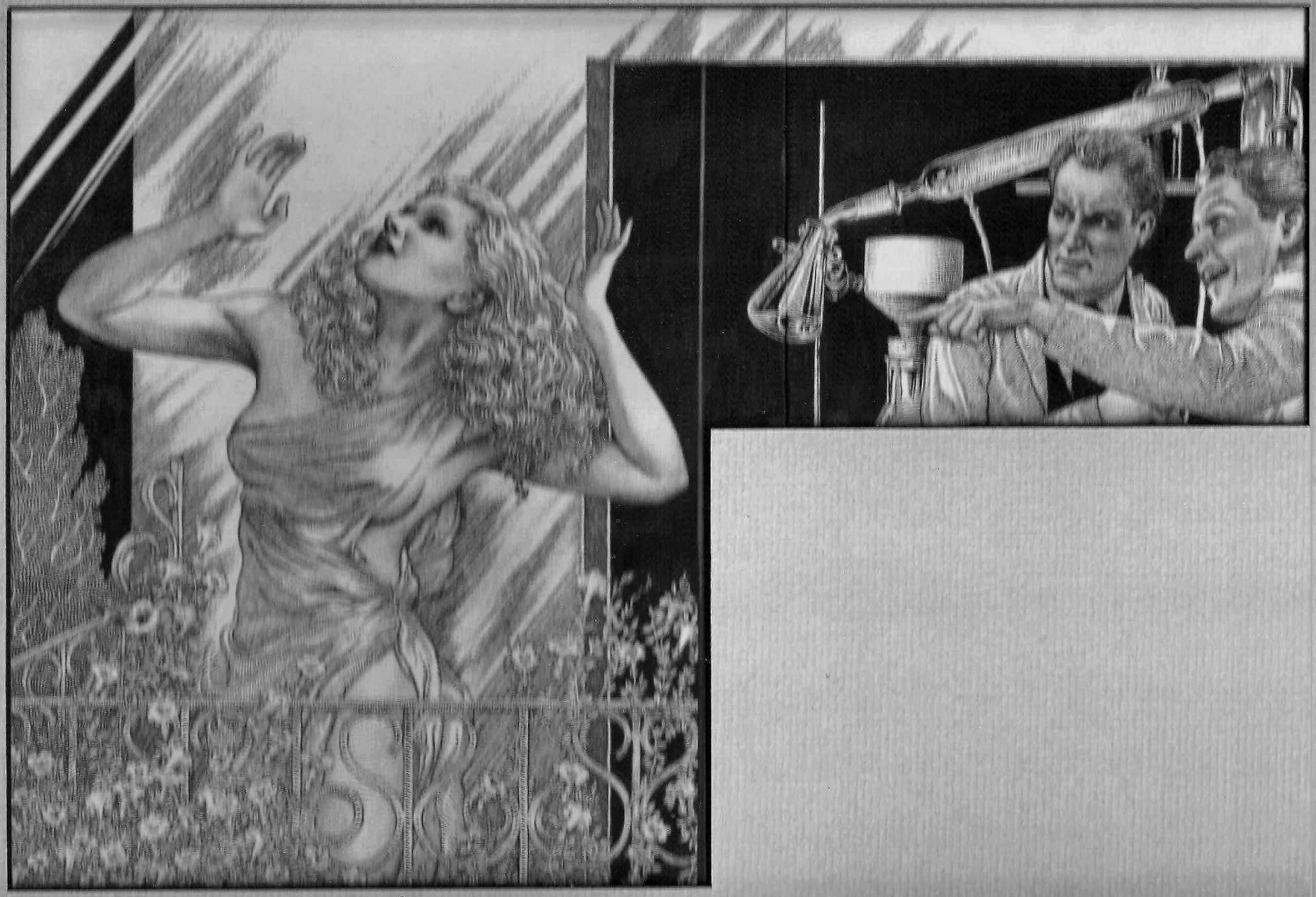

So, I began searching through my science fiction pulp magazine collection, looking for the illustration. Knowing that Howard often visited the publishing offices of Ziff-Davis magazine in the 1940s, and that Ziff-Davis published Fantastic Adventures and Amazing Stories, I thought it a good bet that the art might have come from one of those magazines. And, I was proved right, as I stumbled across the illustration fairly quickly. It was the trailing piece of a double page spread. On the other page was a full page illustration of a beautiful girl. This small piece was two scientists staring at the girl who is in a laboratory test chamber. The title of the story was “The Test Tube Girl.” Pretty damned good, I thought, feeling a great calm settle over me.

But wait, there’s more. A month later, I attended PULPcon, at that time the one convention aimed at pulp magazine collectors. I was sitting in the hospitality suite Friday night when I saw an old friend, Ray B. from Indiana. I had known Ray for years and he had even sponsored my entrance into First Fandom. He was another collector who had started buying pulps in the 1930s, and he had a small but excellent art collection.

After we talked a short while about who was at the convention and what we hoped to find, conversation turned to art. Ray was looking to do some trading and he knew I was always open to making a deal. So, he mentioned what he wanted to let go. It was a Finlay, a very nice one, a piece he had gotten from Ray Palmer back in the 1940s. It was part of a double-page spread and Ray felt certain he would never find the other half, so he wanted to let his half go for something else. The name of the piece was “The Test-Tube Girl.” If Donald Trump had walked into the hospitality suite and asked me if I wanted to go out for coffee, I would not been any more shocked. I traded Ray a very nice Finlay for his and, a few days later, with trembling hands, assembled the two parts of the illustration. The two pieces had been separated with a sharp cutting blade and they fit together perfectly. Which is exactly how I got them framed. So don’t try to tell me that miracles don’t happen in science fiction collecting!

After we talked a short while about who was at the convention and what we hoped to find, conversation turned to art. Ray was looking to do some trading and he knew I was always open to making a deal. So, he mentioned what he wanted to let go. It was a Finlay, a very nice one, a piece he had gotten from Ray Palmer back in the 1940s. It was part of a double-page spread and Ray felt certain he would never find the other half, so he wanted to let his half go for something else. The name of the piece was “The Test-Tube Girl.” If Donald Trump had walked into the hospitality suite and asked me if I wanted to go out for coffee, I would not been any more shocked. I traded Ray a very nice Finlay for his and, a few days later, with trembling hands, assembled the two parts of the illustration. The two pieces had been separated with a sharp cutting blade and they fit together perfectly. Which is exactly how I got them framed. So don’t try to tell me that miracles don’t happen in science fiction collecting!

Image: Test Tube Girl (Part #2) by Virgil Finlay

Image : Test Tube Girl by Virgil Finlay

Image : Test Tube Girl by Virgil Finlay

Back to the 1970s. Gerry de la Ree served as godfather to many a collector interested in getting into science fiction art in the 1970s and 1980s. Gerry had helped Virgil Finlay sell some of his originals when the artist was diagnosed with cancer back in 1970. Gerry had bought many of Finlay’s best illustrations for his own collection. He also had tracked down and bought art from numerous other artists from the 1940s up to the present. Gerry even published a line of hardcover art books featuring some of Finlay’s finest work, as well as books devoted to Bok, Stephen Fabian, and Edd Cartier.

I learned a lot about collecting from Gerry, as did my partner at the time in publishing, Victor D. I think Gerry was amused by our scrambling around looking for Finlay originals. Thus, it was no big deal to him when he suggested in a casual conversation one day that we should ask the publishers of Astrology magazines if they had any Finlay art in their files. Finlay had done many pieces of art for those magazines, and he also had sold them secondary rights to many other pieces he had done years before. Since Finlay had been dead for years, and the Astrology publications insisted they bought all rights to the art, it seemed quite possible they still might have some of his originals, including art that had been done for earlier magazines but used as reprints in their publications.

The suggestion turned out to be worth its weight in gold. Or at least in dollar bills. The biggest Astrology publisher had thirty Finlays and was willing to sell them to us for a reasonable price. Considering that at the time, Finlay black and whites were selling for hundreds of dollars per illustration, it was a tremendous deal. Victor D. and I each ended up with fifteen Finlay originals for the approximate cost of one or two.

In 1980, Doug M. who had sold me several Amazing Stories covers for $30 each approached me with another deal. This time, the price was quite different. Doug had bought a Roy Krenkel painting for the DAW paperback, When the Green Star Wanes by Lin Carter. Doug liked the art but he had paid $400 for it and he needed for something else. I had always been a huge Krenkel fan and I realized the chances to buy a painting by him were few and far between. So I bought the painting from Doug and it has hung in my living room ever since.

Art was turning up so fast I was running out of money.  Fortunately, the book business I ran with my wife was doing well and the art deals I was making often turned a profit, as I kept one or two pieces and sold three or four to a list of eager collectors. In the early 1980s, I bought a cover from Clues Detective Magazine from 1941 and a Rudolph Belarski cover for Thrilling Adventures pulp from 1938. Pulp magazine cover paintings were scarce and there were plenty of collectors who wanted them. The paintings were usually done with oils on canvas and were two feet by three feet in size. Because they were so huge and so rare, most pulp covers sold for $1,000 or more. At the time, most science fiction art sold for much less than that.

Fortunately, the book business I ran with my wife was doing well and the art deals I was making often turned a profit, as I kept one or two pieces and sold three or four to a list of eager collectors. In the early 1980s, I bought a cover from Clues Detective Magazine from 1941 and a Rudolph Belarski cover for Thrilling Adventures pulp from 1938. Pulp magazine cover paintings were scarce and there were plenty of collectors who wanted them. The paintings were usually done with oils on canvas and were two feet by three feet in size. Because they were so huge and so rare, most pulp covers sold for $1,000 or more. At the time, most science fiction art sold for much less than that.

Image: Thrilling Adventures cover by Rudolph Belarski (1938)

In mid-1981, Publishers Weekly, the magazine of the book field, began running a classified ad section in the rear of the magazine. For some unknown reason, they decided that one section of the classified would not be devoted to business ads or help wanted postings. Instead, the section could only be used for personal ads from people in the book field. Having scored with two pulp covers in the past year, I decided to run an ad looking for art. I spent fifty dollars and ran a classified ad saying that I was looking for pulp or paperback art, and that I was paying good prices for anything available. The ad appeared in mid-summer and ran for weeks and weeks. I waited and waited and got no reply. At least, I received no letters about my ad till six months later.

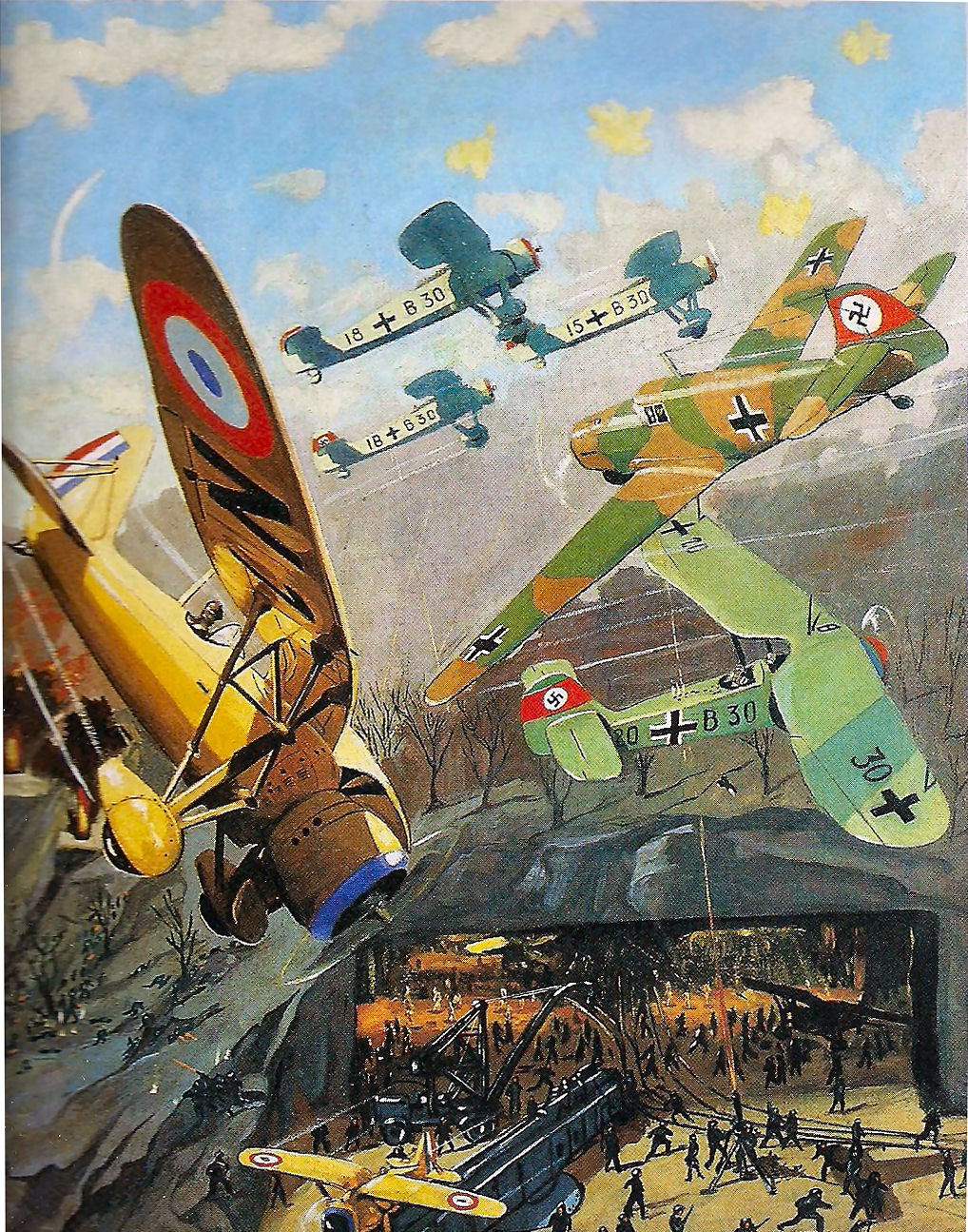

In spring 1982, I received a letter about my classified ad. The writer lived in southern New Jersey and mentioned how he had seen the classified ad in PW but couldn’t decide if he wanted to sell his pulp paintings or not. He went on to write that he had bought twenty-one oil paintings on canvas by Frederick Blakeslee in a New York Used Bookstore years before and would be willing to sell some of them if I was interested. If I was, I should give him a call.

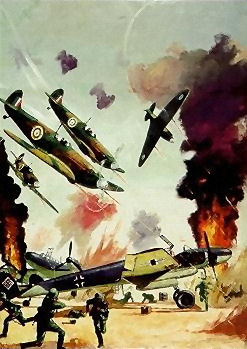

Blakeslee I knew was the premier air war painter for the pulps. His covers were famous for their action scenes of airplane warcraft. He was responsible for hundreds of covers used on Popular Publications air war pulps such as Daredevil Aces, Battle Birds, and G-8 and His Battle Aces. Needless to say, I called this New Jersey collector the same day. And I learned more about his incredible score.

He had been working in the publishing field in the late 1950s in New York City. On his lunch hour, he liked to browse through the used book stores in lower Manhattan. The same stores I went searching through in the early 1960s. One day, he was in the store and the owner showed him a shopping bag filled with rolled up pieces of canvas. He had just bought twenty-one cover paintings from the air war pulps, all by Frederick Blakeslee. After much talk, the owner of the store agreed to show them to the New Jersey collector. The guy wasn’t really interested in the pulps, or in air war magazines. But, he thought the pulp covers were fascinating and very colorful.

So he made an offer. The bookstore owner had gotten the art cheap. The guy from New Jersey doubled the price and bought all twenty-one pieces. He had brought them home that night in the shopping bag they had been kept in by the bookstore owner, and put the bag in a closet. Which is where they had remained for more than twenty years, until he had noticed my ad in Publishers Weekly. And decided that maybe it was time to sell the paintings.

A week later, I flew in to Newark airport to visit my parents and to drive to south Jersey. I looked at the paintings and made an offer for all of them. The owner wanted to keep two, as souvenirs of his incredible buy, but sold me the rest. I paid him a good price compared to what he had paid for the art and he was quite happy with the return on his investment. I was equally happy with what I paid for the pieces. Plus, it was a good excuse for me to see my parents for a weekend. I should mention here that ten years later, I bought the final two paintings from the New Jersey letter writer when he finally grew tired of them.

A week later, I flew in to Newark airport to visit my parents and to drive to south Jersey. I looked at the paintings and made an offer for all of them. The owner wanted to keep two, as souvenirs of his incredible buy, but sold me the rest. I paid him a good price compared to what he had paid for the art and he was quite happy with the return on his investment. I was equally happy with what I paid for the pieces. Plus, it was a good excuse for me to see my parents for a weekend. I should mention here that ten years later, I bought the final two paintings from the New Jersey letter writer when he finally grew tired of them.

Image: Air war pulp cover by Frederick Blakeslee

In retrospect, the deal for the Blakeslee paintings had to be one of the most incredible finds I’ve ever encountered. The man who had bought the paintings was not a pulp fan or collector. He had bought the paintings on a whim, because he liked the bright colors on the canvas. Once bought, he had never done a thing with them, for nearly a quarter of a century. Neither he nor the bookstore owner had any idea as to the identity of the person who sold the paintings to the bookstore for next to nothing. The paintings were from several different Popular Publications magazines and spread out over a period of fifteen years. The personal section of classified ads that ran in Publishers Weekly was judged a failure and was soon dropped by the magazine. That it had been seen, cut out, and saved by the New Jersey owner of the paintings was quite astonishing. All in all, it was an incredible deal.

Over the next several years, I sold most of the air war covers.  While I liked them quite a bit, they really didn’t fit in my collection and I felt no guilt in selling them. I did sell some of the pieces at fairly low prices to help pay for the cost of the collection, but once that money was made, I settled on a price of a thousand dollars a painting. The air war find provided a cushion of extra money for my art collecting over the rest of the decade. It was a fortunate coincidence.

While I liked them quite a bit, they really didn’t fit in my collection and I felt no guilt in selling them. I did sell some of the pieces at fairly low prices to help pay for the cost of the collection, but once that money was made, I settled on a price of a thousand dollars a painting. The air war find provided a cushion of extra money for my art collecting over the rest of the decade. It was a fortunate coincidence.

Image: Battle Birds cover by Frederick Blakeslee

I should mention here that while I would happily claim that my success as an art dealer and collector was the result of my brilliance and wisdom, I realize that my intelligence had little to do with my success. Not that it had none, but very little. I was smart enough to run the advertisement in Publishers Weekly, but it had been sheer luck that the man from New Jersey had seen the ad. Just as it had been incredibly lucky that he had bought the pulp paintings even though he was not an art collector or pulp magazine fan. Incredible, amazing luck was the force guiding that deal and many of the other deals I made in my years and years in the science fiction art field. I was well aware of that fact. After every deal, I found myself saying to my wife, “there will never be a deal like that again. Never!” And I believed those words — until the next incredible deal came along.

Which brings us to Roger and another incredible deal.

Two

Not counting my deal for the air war originals, the early 1980s started off slow for my art collecting. I won several illustrations from an art auction on the west coast. Unfortunately, the two Finlays I bought were on illustration board that had yellowed with age. Despite their excellent illustrations, I just wasn’t happy with either of them. I sold the two to a collector in Japan. The only piece I kept from the auction was a William Terry cover painting for Imagination from 1954, “Peril of the Star Men.”

In 1983, I served as chairman for the World Fantasy Convention, Chicago. As the name implied, the convention was a yearly affair, held in a different city on Halloween weekend. I headed a group of fans who wanted to bring the prestigious con to Chicago. I also served as co-cordinator of the programming.

As a collector, one event that I missed being held at conventions was an auction for rare items. Most big conventions had an auction for paintings offered in the art show. However, no modern convention had auctions where members of the show could put one or two precious items up for sale to the highest bidder. I decided to run such an auction. Not sure what items would be put into it, or if any items would be put in the auction, I went out and bought several rare items just to make sure the auction had some stuff worth buying.

On a trip to the East Coast that summer, I stopped in to see Gerry de la Ree. I told him about the auction I was running, and asked him if he had any art art I could buy to put in the auction. He did. Gerry had two Bok black and whites from Super Science magazine from 1950. The art illustrated a story by A.E. van Vogt, “The Earth Killers.” Gerry had grown tired of the two pieces and sold them to me that day. It was difficult for me to put the Bok art in the auction, since, at that time, I still had no Bok originals in my own collection, and I especially liked art that illustrated van Vogt stories. Still, I had bought the pair to hype up the auction, so I reluctantly placed the two originals up for sale.

I shouldn’t have worried. Notice of the auction appeared in one of the progress reports for the Convention and a number of collectors brought rare items with them that they wanted to sell. Lots of fans and collectors find themselves in possession of one or two items they no longer want or need. But the cost of paying for a dealer’s table at a convention is too much. Nor does sitting behind a table for hours, hoping to sell one or two items, appeal to most collectors. Selling those one or two items at an auction is the way to go, and our auction was filled with rarities.

There was a letter signed by J.R.R. Tolkien, a first edition set of The Lord of the Rings, a half-dozen manuscripts from Weird Tales, and much much more. The two Bok illustrations, which went up for bid near the end of the auction and didn’t meet the reserve, which was the price I paid for the pair. I wasn’t the least bit upset. The auction was a huge success, and I ended up paying for the Boks, which are still in my collection.

Running the World Fantasy Convention, even with the help of many hard-working friends and relatives, kept me busy for most of 1983. My art deal with the guy in New Jersey took plenty of time in 1982. All of which made me think that the rest of the eighties would be a lot less busy. I should have known better.

All of which leads to Roger.

Three

My second “Deal of a Lifetime” (the first “Deal of a Lifetime” was the Ace paperback cover deal) started innocently enough with a phone call from Chicago art collector, Alex E. He had just returned from Kublai Kon, a southern science fiction convention in the late summer of 1985. While inspecting paintings in the art show, he had run into a guy named Tom E,, another hardcore art collector. In the course of conversation, Tom mentioned to Alex that he had bought several Ed Emsh paintings from a fellow in Florida who had a lot of art from Pyramid Books, a well known paperback publisher. Alex had been wise enough to ask Tom if he might have the guy’s name and phone number available, and sure enough, he did and he gave them to Alex. The seller lived in Tampa, Florida. While Alex wasn’t too anxious to contact an art dealer in the Deep South and negotiate the long-distance sale of some artwork, he thought I might be willing to do so. I was. I promised Alex if I got anything good from this art dealer, I would certainly make sure Alex got a finder’s fee. And then, I called the guy, whose name was Roger.

My conversation with Roger went well though I hung up somewhat confused by what he had told me. As best I could determine, Roger had bought the contents of the Pyramid Books warehouse several years before and owned over 1,000 paintings used by that company and its various imprints. He had all the paintings stored at a warehouse in Tampa and was willing to let me take a look at them. He sold the art, and he set his prices by quantity, not quality. The last point didn’t make much sense to me, but I figured I would understand what Roger meant when I saw the paintings.

By an odd coincidence, as seemed to dominate all of my art deals in those days, I was scheduled to visit my sister in Washington, D.C. the following weekend. I was scheduled to fly in Thursday night and see my sister, Sue, and her family that evening. The next morning I was going to the Library of Congress to do research. Sue’s husband, Doug, who worked in Washington, was going to take me into the city and pick me up after work. It was a great arrangement that saved me a lot of money and time. I was then scheduled to fly home to Chicago on Saturday. After my conversation with Roger, all I did was change my flight so that Saturday I flew down to Tampa, and returned to Chicago the next morning. On Roger’s advice, I brought with me my largest leather art portfolio. He said I would need it, and his advice proved correct.

My trip to the Library of Congress proved useful and I flew down to Florida at 7:00 AM on Saturday. I never before ate breakfast in an airplane and it was not particularly exciting. All the excitement was to come a few hours later.

We landed in Tampa about an hour later. I got off the plane carrying my portfolio at my side. The stewardess had been quite pleasant handling the big leather briefcase and had stored it sideways in the coat closet in the front of the plane. The weather in D.C. was quite warm and no one had worn a coat. In Tampa, it was well over 90, with the temperature heading towards 100. I had no idea what Roger looked like, but I was the only passenger who had gotten off the plane carrying a huge black leather portfolio. I figured I was an easy target.

I was. Roger came up to me only a few minutes after I got off the plane and introduced himself. He was about six feet tall, slender, and clean shaven. He wore a white polo shirt and white shorts. His skin was a deep golden brown, the color it gets after years and years of being in the sun. He looked around 40, approximately my age, and to my surprise, when listening to him closely, I realized he had a Chicago accent.

As we walked to Roger’s van, he confirmed my suspicion. He was originally from Chicago. He had moved to Tampa years ago for reasons he left unexplained. While growing up in Chicago, he had run an art business with his father. Their most famous deal was selling a fabulous Norman Rockwell painting featuring the Cubs to a private collector for hundreds of thousands of dollars. That had been big money at the time. Now, he only wished he had the painting again, as he could have gotten millions for it.

Leaving the airport in Roger’s van, we drove along the highway leading into the city. As we passed long stretches of beautiful beaches, inhabited it seemed by numerous good looking women in skimpy bathing suits, Roger asked me how old I thought he was. It was an odd question, out of the blue, and having nothing to do with art. But, I saw no reason not to answer. I told him I thought he was in his early forties.

Roger laughed. He sounded pleased. “I’m fifty-five,” he said. “That’s one of the two reasons why I live in Tampa. It’s always beautiful weather here so you don’t age as fast.”

Then, he asked me another question. “Can you guess the other reason I live in Tampa?” I had to admit I couldn’t. He laughed again.

“Because you can play golf here 365 days a year,” he told me. “I work on my business when necessary in the morning and the best of the day I play golf. At night, I go out dancing.”

That was Roger, one of the most unusual persons I ever met in the art field. By now, sitting next to him in his van, I had reached the conclusion that anything he told me would not surprise me. But I was wrong. Roger still had some surprises up his sleeve.

Getting off the highway, Roger drove the van to an attractive bungalow on a city street. He pulled up in the driveway and told me he would be back in a minute. He used a key from a ring on his belt to let himself into the house. He emerged a minute later with another keyring with a dozen or so keys dangling from it. As he got back into the van, an attractive woman dressed in a white robe appeared in the doorway. She waved as we drove off.

“My ex-wife,” said Roger in explanation. “She works for me as my secretary and billing agent. Normally, she opens and closes the art warehouse. So she keeps the keys at her house.”

Sure. Why not? Didn’t everyone employ their ex-wife as their secretary?

The warehouse proved to be a storefront in the middle of a strip mall about six blocks away. Located in the midst of a Tampa residential neighborhood, two doors down from a 7-11, it definitely didn’t look like an art warehouse. Honestly, it didn’t look like much. At least, not until I stepped inside.

The store front consisted of one large room, approximately 12 feet wide and 22 feet long. The ceiling I guessed was about 8 feet high. The front door was located in the center of the front wall, which was made up of several huge panes of glass. There was a small bathroom in back of the main room.

In the front of the room were two desks, each with a chair, one desk on each side of the front door. This is where all the business was done. A typewriter and file sat on top of one desk. On the top of the other desk were stacks of photos, with rubber bands holding big batches of pictures together. The desks and the space behind them for the chairs was approximately five feet. After that, stretching back the rest of the length of the room, was the “warehouse.” There was a foot wide table on the right and left side walls of the room. Next, fronting those tables, was a two foot aisle. Subtracting the six feet taken up by outer table and aisle on each side of the room left a total of six feet. That space was taken up by twin wood storage units, each of which was three feet wide, three feet deep, and four feet high. These storage units were stacked two high, from floor to ceiling, and went back fifteen feet, leaving a narrow two feet cross-aisle in the rear of the store. With five storage units per row, two rows of units per side, and two sides to the warehouse, there were thus twenty rows of wooden storage units.

The storage units had back walls made of thin plywood but otherwise were constructed of sturdier stuff. They had to be as each of the twenty units held dozens of framed paintings. The storefront was exactly what Roger had called it, a warehouse. Each unit had a number and each painting had an identification number locating it in the proper unit. The paintings were all on photos, and the photos were marked with the code for the unit and where it was in relationship to other paintings in the wooden storage location. Thus the photo of a painting marked 410 could be found in storage unit four, and about ten paintings in from the left side of the box. Sitting in one of the desk chairs, I listened as Roger described the contents of his warehouse. Two years earlier, he had been offered approximately 1200 paintings published by Pyramid paperbacks and their various specialized lines. After negotiating the best possible deal on price, Roger had bought all of the pieces. He had considered making up a catalog of the paintings but rejected the idea as too time-consuming and too slow a method to sell so many paintings. He wanted to sell the art in volume so he had enough time to play golf every day. So he came up with a plan to wholesale art.

His first step was to hire two college students for the summer. With their help, he photographed every painting. Next, he had them frame under glass all twelve hundred paintings. They bought the framing material in huge quantities and got a great price on glass and spent the rest of the summer working hard. When they finished framing the art, the two students placed all of the art in storage units. Then they marked each painting with the identification number that located it in a storage unit and marked its photo with the same number. Thus, after looking at a photo, you could immediately go to the correct storage unit in the warehouse and pull out the correct painting.

Now, twelve hundred paintings framed were too much for the storage units, but Roger managed to sell a lot of the art extremely fast. He contacted a number of large corporations and offered them paintings at wholesale prices. The amount started at $100 for one to ten paintings. If the company bought eleven to twenty paintings, they were $80 each. If the company bought twenty-one to thirty paintings, they cost $70 each. And so on and so on, up to eighty-one paintings, that cost $30. From there on, paintings were no cheaper.

What Roger offered was cheap decorations. These big companies had big offices to decorate and Roger was able to supply interesting and unusual artwork, already framed, to hang on the walls. It was an offer too good to pass up and he had managed to sell hundreds of paintings before I ever made it to his warehouse. Fortunately, from what he told me, the major corporations he dealt with were rarely interested in paintings with much action, and they had selected what I considered the most boring of the paintings. When I visited Roger in the fall of 1985, he still had many hundreds of paintings and as best as I could tell by looking through photos, none of the science fiction pieces had been bought by the big corporations. A few SF pieces had been sold to southern science fiction fans at Kublai Kon where the two college students had set up a small display of Roger’s paintings with hopes of making a bigger profit, but not many.

Roger suggested I sit at one of the desks and go through the stacks and stacks of photos of the original art. Those pieces already sold had been removed from the decks and everything that remained was on the shelves. It would take me hours to go through the more than six hundred pictures. However, it would have taken me days to go through all of the paintings. Roger would pull out all the pieces I wanted to see up close, but otherwise, the easiest way to buy paintings was just to use the photos.

I agreed and with a short break in the afternoon for a box lunch that his ex-wife and secretary brought over, we spent the entire day till five in the afternoon reviewing photos. At five, Roger informed me that we needed to grab a quick supper as he had to get ready for the evening. I assumed he was going to drop me off at a nearby motel for the night, but he insisted that I stay at his condo. He shared an apartment with a friend who was in the Coast Guard and the roommate was off on maneuvers that weekend. I agreed since Roger told me I could bring the photo decks with me and continue going through them all night. I did exactly that. In the meantime, Roger ate a full head of steamed broccoli for dinner — it turned out he was a strict vegetarian — and went out dancing till three A.M.. By then, I had long gone to sleep after going through the stacks and stacks of art photos several more times. In total, I had come up with fifty-nine paintings I wanted to buy. By Roger’s chart, that meant the art would cost me $60 a painting. I was hoping I could bargain Roger down to the next price break, which occurred at 60 originals, and get the better price of $50 a painting even though I was missing the goal by one painting.

The next morning, I made my appeal to Roger. No dice. The price list was set in stone. If I wanted the price of $50, I had to take 60 paintings. If I only took 59 paintings, I had to pay the higher $60 price. Roger refused to budge and I could not change his mind. More to the point, I had a flight back to Chicago at 9 AM that morning that I had to make. We had to complete the deal and figure out the logistics involved before then.

The next morning, I made my appeal to Roger. No dice. The price list was set in stone. If I wanted the price of $50, I had to take 60 paintings. If I only took 59 paintings, I had to pay the higher $60 price. Roger refused to budge and I could not change his mind. More to the point, I had a flight back to Chicago at 9 AM that morning that I had to make. We had to complete the deal and figure out the logistics involved before then.

I finally gave in and picked another painting. In the end, I bought sixty paintings for $50 each, a total of $3,000. I paid Roger half the money, with the rest to be paid on delivery of the art. He was planning a trip to visit his father in Chicago in two weeks and would deliver the paintings to my house then. In the meantime, just to show my wife what I had been looking at, I crammed four of the best pieces of framed art into my huge portfolio to take home by plane. And Roger drove me back to the airport.

My trip home proved to be somewhat more eventful and exciting than planned. I should have known better than to pack four framed paintings, under glass, in a large black leather portfolio. Even though this was many years before tightened airport security, the ticket takers at the airline checkpoints looked at me with suspicious eyes. “That won’t fit in the overhead bin,” was the mantra I heard a number of times that day.

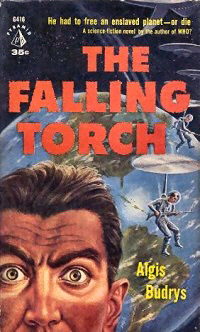

Image: Cover for Algis Budrys’ The Falling Torch

Fortunately, I had the business card with a scribbled note on the back given to me by a friendly fellow art collector who worked for a famous institute that dealt with art in Chicago. The note affirmed that I was a painting scout for that institute. Thus, I claimed with righteous anger that I was on a buying trip for that establishment and had paintings with me that I was delivering to them in the Windy City. With morning temperatures in Tampa hovering around 100, I knew that the front coat closets would be empty. So did the captain of the stewardess team for my flight, whom the clerks summoned from the plane to deal with my request. She merely smiled at my problem and welcomed me on board the flight. The paintings got the front closet and I was seated before anyone else entered the plane. Problem solved

I returned home exhausted but happy. Pyramid had been a minor player in the science fiction field, and I had not been a big fan of the books they had published. Thus, I had not bought many science fiction covers. However, I had found a number of paintings done by the very collectible artists, Robert McGinnis and Robert Maguire, as well as a bunch of stunning pieces by a forgotten artist named Paul (no relation to the SF artist of the same name). Plus, there were several Emsh covers and several quite good John Schoenherr paintings. All in all, it was a tremendous buy. I was able to sell a number of the pieces for excellent prices and I made back my money many times over.

I never made up a list of the art I bought from Roger. Most of it I sold to collectors who visited my home that fall. Most of the mystery and glamorous art cover paintings (known in those days as “good-girl art”) I sold at the Chicago Comic Book Convention the next summer. Word of a good buy traveled fast from one art collector to another in those days. It still does.

I never made up a list of the art I bought from Roger. Most of it I sold to collectors who visited my home that fall. Most of the mystery and glamorous art cover paintings (known in those days as “good-girl art”) I sold at the Chicago Comic Book Convention the next summer. Word of a good buy traveled fast from one art collector to another in those days. It still does.

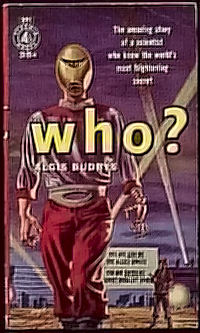

Image: Cover (first edition) for Algis Budrys’ Who?

The science fiction and fantasy art trickled out of my possession over the next ten years. Perhaps my favorite of the entire batch was the original paperback cover art for Who?, the novel by Algis Budrys. I had seen the book on the newsstand when I was a pre-teen and had always been fascinated by the half-human, half-machine being that dominated the cover. Owning the original was a thrill. It proved to be the lynch-pin in a major art trade I made years later, but I miss that painting still.

Here are the names of some of the pieces I obtained in that deal. All of the paintings for books listed, if they had variant covers, are for the first printings.

Farm Girl

The Sea Tyrant

African Mistress

The King’s Mistress

Just Married (Cartoons)

Pirate Wench

Yankee Trader

Hellflower

Who?

The Falling Torch

The Divine Passion

Tomorrow and Tomorrow

The Golden Rooms

The Darkness and the Deep

The Divine Passion

My Holy Satan

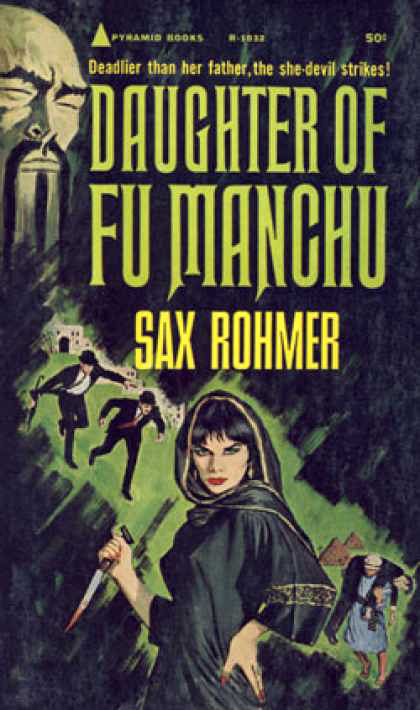

Daughter of Fu Manchu

Trail of Fu Manchu

Re-enter Fu Manchu

Bogey MenThe Green Rain

Masters of the Maze

Joyleg

Lest Darkness Fall

The Great Explosion

Man of Two Worlds

I gave my friend Alex E. the John Schoenherr painting for The Green Rain for giving me Roger’s phone number.

Twenty five years later, I find that the only pieces I still have from that incredible deal, of being able to pick out the top sixty paintings (in my opinion) from over six hundred originals, are several covers used to illustrate Sax Rohmer’s famous Dr. Fu Manchu series, that was published complete in paperback by Pyramid Books. All the other paintings I obtained from Roger have gone to other collectors, either sold or traded. I can’t complain, as without the money I raised by selling some of those paintings, and without the deals I made by trading others of those paintings, my collection would be much less interesting and exciting. Collectors can’t cry over the pieces that have passed through their hands. Every painting that you own, even for a day or two, is a step in the right direction, in assembling the collection you own today.

Several years after my dealings with Roger, a book dealer who also specialized in paperback art, asked me for Roger’s contact information. I saw no reason not to give it to him. The next year, the dealer had a number of paintings from Roger’s warehouse for sale at PULPcon. I never did find out what Roger did with the rest of his pieces. Though it’s been twenty-five years since I last saw him, and he would be just past eighty years old, it’s hard not to imagine Roger still playing golf in Tampa and going out dancing every night. He was definitely one of the most memorable characters I ever met in dealing in original art.

Several years after my dealings with Roger, a book dealer who also specialized in paperback art, asked me for Roger’s contact information. I saw no reason not to give it to him. The next year, the dealer had a number of paintings from Roger’s warehouse for sale at PULPcon. I never did find out what Roger did with the rest of his pieces. Though it’s been twenty-five years since I last saw him, and he would be just past eighty years old, it’s hard not to imagine Roger still playing golf in Tampa and going out dancing every night. He was definitely one of the most memorable characters I ever met in dealing in original art.

Image: Cover for L. Sprague de Camp’s Lest Darkness Fall

I remember quite well, saying to my wife the day after Roger delivered the paintings to our house in the Chicago suburbs, that this was the deal of a lifetime, being able to select sixty paintings from the Pyramid library of paperback covers. I was convinced that I would never encounter a deal of such significance in the art field again. I recall saying that, along with my deal selling covers from Ace books, that I had reached the pinnacle of art collecting and there were no more worlds to conquer.

My wife, Phyllis, who was much wiser than me, didn’t say a word.

Next time: Lail; it rhymes with Gail

(My apologies to the readers of this series for the lack of illustrations this installment. To be perfectly honest, I foolishly did not photograph most of the originals I bought during this period. Since all but a couple of pieces are long gone, I have no photographic record to illustrate Art Mania. Next installment, I promise, will be quite the opposite!)