Robert Weinberg continues his personal look back at the earliest years of his almost four decades of collecting science-fiction and fantasy art with this second installment, which he titles “Aces and Earls.” Bob recounts more of the valuable connections he made early on, including those of Sam Moskowitz and Gerry de la Ree, and how he came into possession of one of the largest finds in his collecting career. Once again, we thank Bob for providing this on-going historical perspective (which has all the earmarks of a book in the making somewhere down the road), and also for providing select pieces from his personal collection (an even dozen) to enhance his fascinating narrative.

Robert Weinberg continues his personal look back at the earliest years of his almost four decades of collecting science-fiction and fantasy art with this second installment, which he titles “Aces and Earls.” Bob recounts more of the valuable connections he made early on, including those of Sam Moskowitz and Gerry de la Ree, and how he came into possession of one of the largest finds in his collecting career. Once again, we thank Bob for providing this on-going historical perspective (which has all the earmarks of a book in the making somewhere down the road), and also for providing select pieces from his personal collection (an even dozen) to enhance his fascinating narrative.

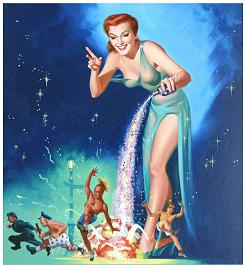

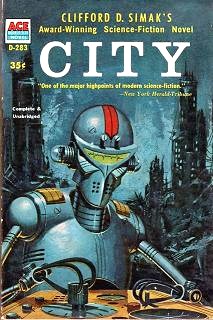

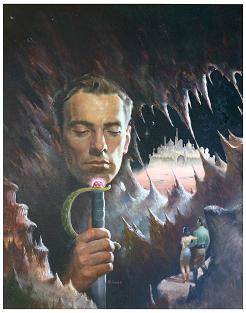

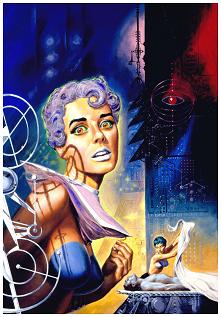

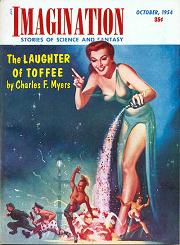

(Cover painting at left by W. H. McCauley for Imagination, October 1954. Cover at right by Ed Valigursky for the first paperback edition of City.)

Collecting Fantasy Art #2

Aces and Earls

By Robert Weinberg

Copyright © 2010 by Robert Weinberg

— One —

After living in apartments for several years, Phyllis and I bought our first home in 1975. While it’s possible to collect art in an apartment, it’s a lot easier collecting when you own a house and you have all the walls you need (or think you need!) to decorate with your acquisitions. I know when we moved into our first house, located right on the border of Chicago’s southwest side, I thought we would never run out of wall space. How little I knew! How fast my collection grew!

During the past several years, Phyllis and I had run a business selling new science fiction and fantasy books and fan magazines. I won’t go into all the decisions that led us to start the enterprise other than mention that with two math degrees I found myself at the time too qualified for most jobs other than working a cash register at a department store. The book business came about mostly from my own complaints on how difficult it was to keep up with fanzines that published material I wanted to read but that rarely let anyone know when they published a new issue. Over time, our business became the one-stop shop for hardcore sf, fantasy, and horror fans looking to expand their collections without having to deal with several dozen fan editors. Within a few years we were doing quite well.

I mention this as a brief introduction and explanation on how I was able to afford to continue art collecting in the mid and late 1970s. In these grim collecting days when hardly any art is offered for sale or trade, it’s difficult to remember a time when art seemed to be everywhere. A week hardly went by without me stumbling upon another deal or some other major collection just waiting to be purchased. Business was very good in those days. We made enough to buy a home. And we earned enough extra money to buy some nice paintings to decorate our living room.

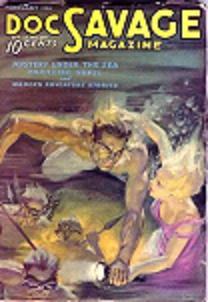

Remember my discussion of the art auction at PULPcon #1? I mentioned that Walter Baumhofer wrote that he owned several slightly damaged pulp paintings that he wasn’t sending to the convention auction but that he would sell if anyone was interested. Well, one of the more ambitious dealers at the show, a fellow we will call Big C, wrote to Mr. Baumhofer and bought those paintings. A few years after PULPcon #1, he offered the originals for sale at $400 each. That was a lot higher than the prices at the auction, but by then, everyone in the field agreed that those paintings had been incredible bargains. One of the pieces Big C owned was the Doc Savage magazine cover from the February 1936 issue, Mystery Under the Sea. As it was that art show that had started me collecting art, and Baumhofer art in particular that had pushed me into art collecting, I thought it only right that I buy that pulp original. It was a wise decision.

Remember my discussion of the art auction at PULPcon #1? I mentioned that Walter Baumhofer wrote that he owned several slightly damaged pulp paintings that he wasn’t sending to the convention auction but that he would sell if anyone was interested. Well, one of the more ambitious dealers at the show, a fellow we will call Big C, wrote to Mr. Baumhofer and bought those paintings. A few years after PULPcon #1, he offered the originals for sale at $400 each. That was a lot higher than the prices at the auction, but by then, everyone in the field agreed that those paintings had been incredible bargains. One of the pieces Big C owned was the Doc Savage magazine cover from the February 1936 issue, Mystery Under the Sea. As it was that art show that had started me collecting art, and Baumhofer art in particular that had pushed me into art collecting, I thought it only right that I buy that pulp original. It was a wise decision.

Around the same time, I got a letter from an antique dealer located on Long Island. He owned a pulp painting by a guy named Parkhurst. A tourist passing through town had given the man my name as someone interested in old art. Thus he was writing me. The antique dealer had an original Spicy Detective magazine cover painting from 1940 and wanted $400 for it. I was quite happy to pay his price and get the painting. I never did find out who had talked to the dealer and given him my name. Too bad, as I would have liked to shake his hand. Thus I added another pulp magazine cover to my ever-growing collection.

It was 1976 and Phyllis and I had some extra money. I was still anxious to find more original art, especially paintings and black and white illos done by top artists in the 1930s through the 1960s. Already, I was beginning to realize that older pieces were quite rare and that they rarely came on the open market. Most sales of old art was between one collector and another.

As a science fiction and fantasy fan originally from New Jersey, I had been fortunate enough to meet some of the best known fans of the time who lived in the Garden State. Among them were Sam Moskowitz and Gerry de la Ree. During the 1970s, I was lucky enough to visit each of them several times. Each visit was an education, as these two men owned great collections of science fiction art and were happy to talk about the hobby and the field.

— Two —

Sam Moskowitz lived in a huge house in Newark with his wife, Christine Haycox, who was a noted sports doctor. Many of the rooms of their home were decorated with early science fiction pulp cover paintings by Frank R. Paul. How Sam had obtained them was one of the great collector’s stories of science fiction.

In 1953, Hugo Gernsback, the father of modern Science Fiction, recruited Sam as editor for his new magazine, SF PLUS. Sam had agreed on the one condition that he received all artwork used for the new magazine. Gernsback agreed and thus Sam obtained a bunch of very nice art for no money. He also commissioned Frank R. Paul, who had left the SF field, to paint some new covers. But, all of this was secondary to Sam’s big score.

One night, as Sam was leaving Hugo Gernsback’s offices in New York City, he noticed several huge garbage drums outside on the curb, waiting for the next day garbage pickup. Wondering why they needed such big drums for waste, Sam opened one and looked inside. In the drums were a number of large, original science fiction paintings done by Frank R. Paul. Sam immediately recognized them as 1929 and 1930s pulp covers for Science Wonder Stories, Air Wonder Stories, and Wonder Stories. All three were magazines published by Gernsback decades before. Evidently, the paintings had been kept in storage for years and years until Gernsback had decided to throw them out to make more room in his warehouse area. Sam rushed back upstairs to his office and asked Gernsback if he could take away the paintings and keep them. Gernsback had no problem with the idea. He was interested only in getting rid of the paintings. So Sam Moskowitz loaded up the taxi cab he had hailed and told the driver to drive him home to New Jersey. It was worth the huge cab fare to transport the more than a dozen rare pulp paintings to his house. The art, cleaned and restored, made an impressive display in Sam’s house and made an even more impressive story for him to tell.

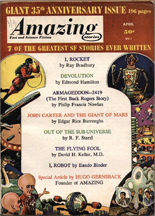

Sam owned another Paul, the last major painting the artist had ever painted, and that too had a story behind it. Christine collected elephants. She had miniature glass elephants, tablecloths with elephants on them, all sorts of decorations and clothing with elephants on them, and much much more. Sam was determined to get her a Frank R. Paul painting for an anniversary present. He contacted the editor of Amazing Stories in 1960 and mentioned that April 1961 would be the 35th anniversary of the magazine. Were they planning to publish a special tribute issue of the magazine?

Amazing had not published a 25th anniversary issue, nor had they published a 30th anniversary issue. But with the urging of Sam Moskowitz, they decided to publish a 35th anniversary issue. Moreover, Sam volunteered to edit the magazine and obtain the reprint rights for the stories in the issue. He even persuaded Frank R. Paul to design the front cover and paint a colorful back cover for the issue, like the back cover paintings the magazine had published in the 1940s. All Sam asked in return for all of his work was that he could keep the back cover painting done by Paul and paid for by the publisher.

Amazing had not published a 25th anniversary issue, nor had they published a 30th anniversary issue. But with the urging of Sam Moskowitz, they decided to publish a 35th anniversary issue. Moreover, Sam volunteered to edit the magazine and obtain the reprint rights for the stories in the issue. He even persuaded Frank R. Paul to design the front cover and paint a colorful back cover for the issue, like the back cover paintings the magazine had published in the 1940s. All Sam asked in return for all of his work was that he could keep the back cover painting done by Paul and paid for by the publisher.

Needless to say, that back cover painting featured elephants. Sam got it as payment for his services for Amazing Stories, and Christine got it from Sam as a present. Such are the ways that science fiction fandom works.

While most collectors who visited Sam’s house marveled over his Frank R. Paul artwork, I was most impressed by a black and white original he owned by Virgil Finlay. A picture of a beautiful woman and a unicorn, it had been completed by Finlay while he had been on Okinawa in World War II. Sam had visited Finlay in the late 1960s and though he had looked at many, many illustrations, had only bought the unicorn piece. In Sam’s opinion, it was Finlay’s finest illustration. I remembered that opinion for years and years that followed.

— Three —

The other major art collector in New Jersey was Gerry de la Ree. I was lucky enough to have visited Gerry with my father when I was only fifteen. Gerry worked as a sports reporter for a Jersey newspaper but his greatest love was science fiction art. He had a wonderful collection of originals by Virgil Finlay, probably the best in the world other than what the artist himself owned. Gerry knew Finlay personally and had been buying originals from him for years.

Gerry sold rare books and pulp magazines as a sideline to help pay for his collecting. He had been doing it since the 1950s and was well known throughout the SF field. From time to time, Gerry even sold original artwork, usually as a favor for the artist. In the late 1960s, Gerry had sold a number of originals for Finlay when the artist contracted throat cancer and needed funds. Finlay had died a few years later and from time to time, Gerry sold originals for the artist’s widow, Beverly. He was a good man, with a somewhat gruff exterior but a heart of gold.

Gerry de la Ree was the premier art collector of classic science fiction during the 1950s through the 1980s. He was an enthusiastic collector who searched high and low for originals. He contacted many of the great artists of the past and bought originals from them that might otherwise have been destroyed. I was by no means the only young (at the time) art collector to visit Gerry at his home where he lived with his wife, Helen. Art collectors from all over the country made the trip to Gerry’s home, which many of us considered the premier location for fantasy art originals in the world. Gerry had many of Virgil Finlay’s finest black and white illustrations hanging everywhere in his house. He had the art framed and thought nothing of putting it up in batches five across and three or four deep on a wall. There was art wherever you looked. Along with Finlay, Gerry had originals by Lawrence Sterne Stevens, Hannes Bok, and Steve Fabian which he displayed everywhere, from the entrance foyer to the kitchen of his huge home. Visiting Gerry was like going on a pilgrimage for science fiction art collectors. Walking through his house was comparable to a religious experience. Most art collectors considered it close to being in heaven. Gerry’s home affected you that way. Some of the major art collectors who were influenced by Gerry de la Ree were Steve L, Stuart S, Victor D, and of course, me, Bob W.

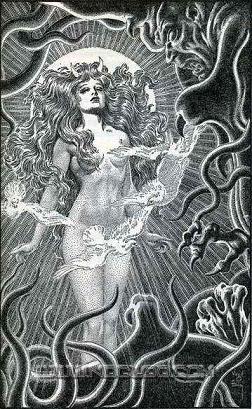

I never asked Gerry which Finlay originals he liked the best. It wasn’t hard to tell. In The Book of Virgil Finlay, the first of six books collecting some of the artist’s work, Gerry had singled out the set of five illustrations Finlay had done for a hardcover version of A. Merritt’s novel, The Ship of Ishtar, as being among the artist’s best work, if not his best. Gerry owned those five and they were proudly displayed on the wall of his library. Along with Sam Moskowitz’s unicorn piece, I thought that those five were Finlay’s best illustrations.

I never asked Gerry which Finlay originals he liked the best. It wasn’t hard to tell. In The Book of Virgil Finlay, the first of six books collecting some of the artist’s work, Gerry had singled out the set of five illustrations Finlay had done for a hardcover version of A. Merritt’s novel, The Ship of Ishtar, as being among the artist’s best work, if not his best. Gerry owned those five and they were proudly displayed on the wall of his library. Along with Sam Moskowitz’s unicorn piece, I thought that those five were Finlay’s best illustrations.

As a collector, Gerry knew all the tricks. He had invented a lot of them. Once, in the late 1970s, I was reading an issue of the science fiction pulp magazine, Planet Stories. The magazine was famous for its letter column where big name fans engaged in wild attacks on each other in print. More important to me was the fact that every issue the readers voted on the three best letters in the previous issue and the editor awarded them with a piece of original art from that issue. I couldn’t help but wonder how many of those originals might still be around? So I went through every issue of Planet Stories, marking off all the winning letters and then wrote them a letter suggesting that if they still had the original art they received from Planet Stories that I paid good prices for such art. I never heard from one person. Not even an acknowledgment they received my letter. I did get back a bunch of moved slips but that was it. When I mentioned my effort to Gerry de la Ree the next time I saw him, he laughed. When I asked him what was so funny, he told me the idea was a good one. So good, he had tried it himself, ten years earlier. He also had gotten no response. Too many years had passed for the information to yield any rewards.

I mention this story for two reasons. One, to demonstrate the extent art collectors were willing to go to find new material. And, two, to show how the craziest notions sometimes pay off.

What do I mean by that? Neither Gerry nor I ever got a letter in response to our queries mailed to the collectors who won art originals given by the editors of Planet Stories. However, as you may have noticed, I have an astonishing memory. Long after I sent out those letters, I remembered the names of the people I had queried. One afternoon, reading a current science fiction magazine, I noticed a letter from one of those Planet Stories fans. He was still alive, still writing letters to SF magazines, but he was at a different address than the one I had mailed my letter to. I wrote to him about his art collection. He answered promptly. He still owned dozens of originals from the 1930s and 1940s and was willing to sell them. It was a totally unexpected but very satisfying end to my letter writing campaign to Planet Stories readers. Plus it proved to me that even the wildest chance was worth taking in the pursuit of original art.

— Four —

In 1975, I entered a limited partnership agreement with another SF collector, Victor D, to pursue original art as a team. We reasoned that if we both could find originals on our own, that both of us working together would be able to find even more. Plus, while I was located in Chicago, he was living in Brooklyn, only a subway trip away from New York, where we felt certain there was still lots of art hidden away in odd locations. A few years later, when Victor graduated college and moved to Texas, we relied on his father who still lived in Brooklyn to be our foot soldier. It was an odd arrangement but it worked. Victor and I named our new company Science Fiction Graphics. Our main purpose and guiding light always was the buying and selling of original art.

Our first score was a good one. I remembered reading in an issue of Galaxy magazine that Robert Guinn, the publisher of the digest mag, was selling original art from the magazines. At the time I read the announcement I was attending graduate school and felt that there was no place for original art in my room. When I later changed my mind, I remembered the Guinn note, but had never followed up on it. Alex E., who had been a major fan of Galaxy and the artists who worked for the magazine, had bought numerous originals from Guinn and I had seen them. They were tremendous pieces of science fiction art. My only concern was that I wondered if Alex had bought all the good pieces. I didn’t have my issues of Galaxy with me in Chicago, so it was hard to remember what the covers were for individual issues, or the interior art that illustrated the stories. But, with Victor as my partner, I felt that I suddenly had a chance to find out what treasures remained with Guinn.

Our first score was a good one. I remembered reading in an issue of Galaxy magazine that Robert Guinn, the publisher of the digest mag, was selling original art from the magazines. At the time I read the announcement I was attending graduate school and felt that there was no place for original art in my room. When I later changed my mind, I remembered the Guinn note, but had never followed up on it. Alex E., who had been a major fan of Galaxy and the artists who worked for the magazine, had bought numerous originals from Guinn and I had seen them. They were tremendous pieces of science fiction art. My only concern was that I wondered if Alex had bought all the good pieces. I didn’t have my issues of Galaxy with me in Chicago, so it was hard to remember what the covers were for individual issues, or the interior art that illustrated the stories. But, with Victor as my partner, I felt that I suddenly had a chance to find out what treasures remained with Guinn.

I flew to New York City on July 4th weekend in 1975 to attend the New York Comic Book Convention. At the time, this show was the biggest comic book convention in the United States and attracted the most fans from all over the country. I had a table reserved for selling stuff at the show and was counting on Victor to supply me with the goods. Galaxy had published a large number of black and white illustrations by comic book artist Wally Wood. I had told Victor to go to Guinn’s office and take all the Wood art he could find and buy it from Guinn at the lowest price possible. Then, we would sell it at the comic book convention for a large markup. I attended the show with nothing in my portfolio other than hope.

Victor came through in spades. He showed up at the show with approximately two dozen Wally Wood originals. All were large size, drawn on illustration board. They were all signed and looked terrific. We sold all but three of the originals at the show for nice high prices and I took home the trio that had not sold and found collectors in Chicago who wanted them. Our first venture as partners paid off big time. So we decided to try again.

This time, we decided to attend the World Science Fiction Convention for 1976, which was held over Labor Day weekend in Kansas City, Missouri. Phyllis and I planned to drive there from Chicago. Victor was going to come from Manhattan, after stopping at Guinn’s offices. This time, he was going to take all the art the publisher would allow him to resell on consignment. That way, we would have none of our money tied up in the artwork. If there was anything we wanted for our own collection, we could still buy it for the asking price minus our commission. All in all, it was a very good plan. Too bad it didn’t seem to work.

This time, we decided to attend the World Science Fiction Convention for 1976, which was held over Labor Day weekend in Kansas City, Missouri. Phyllis and I planned to drive there from Chicago. Victor was going to come from Manhattan, after stopping at Guinn’s offices. This time, he was going to take all the art the publisher would allow him to resell on consignment. That way, we would have none of our money tied up in the artwork. If there was anything we wanted for our own collection, we could still buy it for the asking price minus our commission. All in all, it was a very good plan. Too bad it didn’t seem to work.

Guinn agreed to our proposal and Victor showed up at the show with several hundred originals! There were numerous cover paintings from Galaxy, IF and Galaxy Novels magazines. Along with them were hundreds of black and white illustrations, all on art boards that were usually several feet long. We had two tabletops and two boards behind our tables for display. Needless to say, they proved inadequate for the task of exhibiting all the art we had. Since I wasn’t sure how much art Victor was going to get from Guinn, I had brought a selection of new books and fanzines to put on the tables as well. When the stacks and stacks of art proved too chaotic to sell, I sold new books to pay for our room and board at the convention. The Guinn deal proved to be a disaster for the convention, but attending the show did pay off in some long-term results.

Victor D. who had the paintings for a good amount of time after the convention found several very nice pieces in the mix, including a painting by Virgil Finlay, which he bought for next-to-nothing. We did sell a number of paintings done for Galaxy Novels covers to one of my friends, Sid A, who collected art and was attending the convention. A number of years later, I ended up buying those paintings back from Sid when he was going through a divorce. They remain as a valued part of my collection.

More important, many fans attending the show saw Victor and me selling original art. As the only dealers at the show with two tables devoted to science fiction art, we made a strong impression on the many collectors at the show. By the time we left Missouri, we were both known as the premier art dealers in the science fiction field. That important identification paid dividends for years afterwards.

I should mention that at the show I bought the Lawrence cover painting for Seven Footprints to Satan, from the Fantastic Novels offered to me by Big C. The painting was slightly damaged so I got it for a reasonable price. Repaired and framed, it has hung in my bedroom ever since. It’s my favorite painting and buying it in Kansas City made that convention extra special to me.

— Five —

Life slowed down for Phyllis and I after the World Science Fiction convention. While attending such shows was exciting and filled with all sorts of events and happenings, after a few days on the road we began missing home and peace and quiet. Besides, we had a business to run and that required our attention. So, art collecting got pushed to the side for the rest of the year as we settled back into familiar routines.

In early October 1976, I sent in a credit application to Suits News in Michigan. I felt our business needed to expand and Suits handled all of the mass market paperbacks. My friend, Ray Walsh, who owned the Curious Book Shop in East Lansing, Michigan, spoke highly of Suits, who supplied his store with paperbacks. So, I figured I would give them a try. Days passed and then suddenly I got a call from the company. It was one of their sales people on the line, a fellow named Doug Ruble. He wanted to talk to me. I wasn’t sure why he needed to speak with me, as our application was pretty much standard stuff, but I figured if there was a problem best to find out early instead of late.

It was a phone call that changed my life.

Doug Ruble was the sales person who handled Ray Walsh’s account with Suits News. He was a science fiction fan and knew Ray as a friend as well as a businessman. Doug had attended the 1976 World Con and Ray had introduced me to him, but I didn’t remember him. No matter. He remembered me and my exhibit of art for sale. Doug had a business proposition if I was interested. It dealt with original art. Lots and lots of original art.

Doug Ruble was the sales person who handled Ray Walsh’s account with Suits News. He was a science fiction fan and knew Ray as a friend as well as a businessman. Doug had attended the 1976 World Con and Ray had introduced me to him, but I didn’t remember him. No matter. He remembered me and my exhibit of art for sale. Doug had a business proposition if I was interested. It dealt with original art. Lots and lots of original art.

Doug explained. Ace Books, one of the last small paperback publishers in New York, was in negotiations with the Berkeley Publishing company. It would be years before they finally made a deal, but Ace had a warehouse full of paintings that had been used for the covers of their paperbacks. That warehousing cost money and Ace was determined to drop all unnecessary expenses long before any final merger was announced. So they were anxious to sell all of the original artwork they had in stock. While not every painting done for every Ace book was available, most were. There were hundreds of science fiction covers, some of the best known illustrations in the science fiction field. Doug had just returned from a trip to New York where he had bought all that art on consignment from Ace Books. He needed to sell a lot of those paintings to pay for the rest.

Since Doug had a full time job working for Suits News, he needed help selling the art. Ray had agreed to work with him. Would I be interested as well?

It was the opportunity of a lifetime and I took it. When I hung up the phone, I remember telling Phyllis that “Deals like this only come along once. I’ll never get a deal like this again.” They were words to remember.

Doug had just finished making the deal with Ace, so he didn’t expect to have any lists of paintings for sale for several weeks. In the meantime, I decided to make up a list of five Ace covers that I wanted to buy for my own collection. Ray and I would have first choice of the art, but that wouldn’t last long. Doug needed sales and payments as soon as possible and we were on a tight schedule. If we wanted paintings for ourselves, we had to buy them quickly.

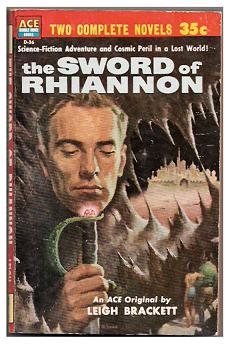

Ray and I turned in our lists to Doug about ten days later. Each of us listed five paintings. My choices were the covers for The Sword of Rhiannon by Leigh Brackett, Conan the Conqueror by Robert E. Howard, The World of Null-A by A.E. van Vogt, Conquest of the Space Sea by Robert Moore Williams, and Big Planet by Jack Vance.

I never did see Ray’s list but I was told by Doug that the only painting we had in common was Big Planet. Since Doug had asked Ray first to work with him and Ray was also his best customer at Suits News, Doug felt that he had to give Ray the Jack Vance cover. I couldn’t argue since everything he said was true. Still, I wanted Big Planet and was determined someday to own it. The book was a favorite of my father, who was also a science fiction fan, and I had fond memories of him giving it to me to read years ago. Sooner or later, if I was patient, I was certain the painting would be mine.

I never did see Ray’s list but I was told by Doug that the only painting we had in common was Big Planet. Since Doug had asked Ray first to work with him and Ray was also his best customer at Suits News, Doug felt that he had to give Ray the Jack Vance cover. I couldn’t argue since everything he said was true. Still, I wanted Big Planet and was determined someday to own it. The book was a favorite of my father, who was also a science fiction fan, and I had fond memories of him giving it to me to read years ago. Sooner or later, if I was patient, I was certain the painting would be mine.

The only other painting available on my list of art treasures that Doug was able to find in the Ace warehouse was the original for The Sword of Rhiannon. What happened to the others was a mystery. Most likely they had been given away by sales people working for Ace Books to the line’s best customers. Strangely enough, I learned the answer to that question many years later.

The Sword of Rhiannon painting was so badly scratched and beat up that Doug gave it to me for free. It was a nice gesture and one that I really appreciated. Doug Ruble was a class act. I brought the painting to my picture framer, Jack Simmerling, and he did a minor touchup, cleaned it, and coated it with varnish. In a nice frame, the painting looked new. It was my first Ace cover, but definitely not my last.

A few weeks later, on October 27, 1976, Doug sent us each lists of art for sale. He had hand-written a list of 137 paintings by Ed Emshwiller and Ed Valigursky, two fine artists who had done a vast majority of the early Ace books during the 1950s and 1960s. Next to each piece, Doug had penciled in the price he wanted to get for the original. Prices ranged from $75 to $200, with a vast majority of the pieces priced at $125 each.

I took Doug’s list, used white out to cover the prices he needed to get for the originals, and put in my prices, usually ten to twenty-five dollars higher per piece. My strategy was to keep the prices as low as possible but make a small profit on each painting I sold. In that manner, I hoped to earn enough money to pay for a number of paintings I wanted on Doug’s list without spending any of my own cash. If no one was interested in buying paintings, I would have bought them with our savings. I sent out copies of the revised list to five of my very best art collectors and sat back and waited for their response. In those days, the post office was still dependable and reliable. A letter mailed in Chicago to Chicago was delivered the next day or two. I mailed out the letters on Thursday, the 28th of the month. I started getting phone calls the next day, Friday the 29th. By Saturday, the 30th, I had heard from all five people to whom I had sent the list. In total, they wanted 19 paintings for a total of $2,925. Using the money I made from my modest markup (about 12% of the paintings’ cost) and another $200 of my own, I bought five pieces.

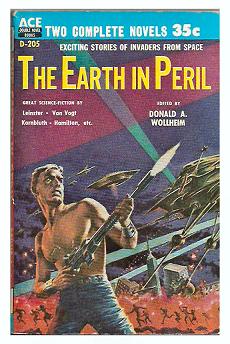

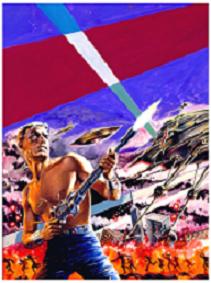

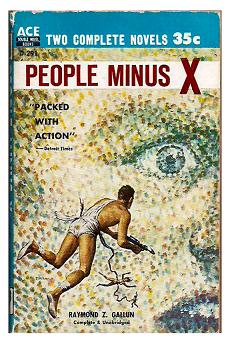

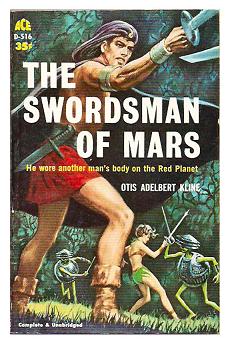

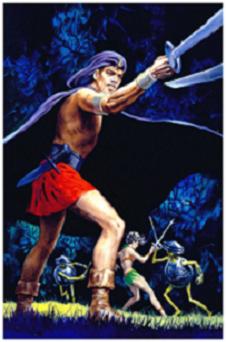

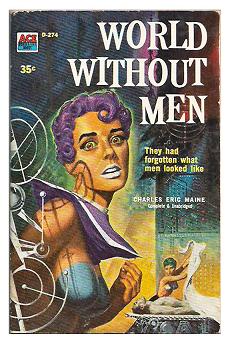

The ones that I bought were for The Earth in Peril, Brigands of the Moon, People Minus X, The Swordsman of Mars, and World Without Men. The first four were favorites of mine. The fifth was picked by my wife. I thought it was pretty garish, even for a paperback cover. Needless to say, we’ve had more offers for that painting than any other piece in our collection. It’s a fact my wife never lets me forget. I don’t blame her. She was right to select that cover. It’s garish but striking. My dislike of the art faded with my memory of the novel it illustrated, one of the worst books Ace ever published.

The ones that I bought were for The Earth in Peril, Brigands of the Moon, People Minus X, The Swordsman of Mars, and World Without Men. The first four were favorites of mine. The fifth was picked by my wife. I thought it was pretty garish, even for a paperback cover. Needless to say, we’ve had more offers for that painting than any other piece in our collection. It’s a fact my wife never lets me forget. I don’t blame her. She was right to select that cover. It’s garish but striking. My dislike of the art faded with my memory of the novel it illustrated, one of the worst books Ace ever published.

Some of the other paintings bought by my customers included The Man With Nine Lives, Recruit for Andromeda, Masters of Evolution, The Hidden Planet, and City. Yes, I sold to one of my customers the cover painting for the first paperback printing of Clifford Simak’s wonderful multi-generational novel, City. The painting was a wonderful picture of a complex humanoid robot writing in a diary in a ruined city. When I collected the money for the paintings to send to Doug Ruble, I remember thinking to myself “I might be making a terrible mistake not buying this painting for myself.” But, I hadn’t taken the piece for myself and I felt it was only fair to let my customer buy it.

The art arrived at my house in a huge shipping box early in 1977. It was a cold, blustery day outside. Inside, in my living room, it was volcanic. It was a memorable moment, opening a box with 24 great paintings by Ed Emsh and Ed Valigursky. For one of the few times in my life, I was stunned to complete silence. Removing the painting for City, I remember thinking, “I definitely have made a terrible mistake.”

Of the five paintings I bought that first time from Doug Ruble, I still own four of them. Brigands of the Moon was part of an incredible trade that I will discuss in a future article.

I sold a lot more paintings for Doug Ruble and bought a number of other Ace covers for my collection during the next several years. Not only did the Ace deal double the size of my collection, it also aided me in obtaining other pieces from collectors, giving me a near unlimited number of paintings to use as trade bait. Plus, having hundreds of paintings for sale, with no money committed to the mix, helped me earn enough cash to put my regular business on a much more solid foundation. The sales of Ace paperback covers helped finance Weinberg Books. Still, though I received plenty of other boxes of originals from Doug Ruble, opening them never again matched the thrill of opening that first box of paintings shipped by Doug.

— Six —

Fortunately, while I thought the Ace paperback covers I obtained during my time working with Doug Ruble were fantastic, they definitely weren’t the best art published in the science fiction field. Those wild and garish paintings by Emsh and Valigursky were great when compared to the work done by most other paperback artists working in the 1950s and 1960s. However, they were nothing special when compared to the great magazine cover paintings by artists like Virgil Finlay, Hannes Bok, Lawrence Sterne Stevens, Harold McCauley, Malcolm Smith, and numerous others. Magazine art helped define modern science fiction and nowhere was that more apparent than in the years from 1950 through 1960. While I was pleased with the Ace paperback covers I obtained for my collection, I was astonished and amazed by the magazine covers I bought a few months later.

In total, Doug obtained and cataloged 493 science fiction cover paintings. Ace Books published plenty of books that weren’t science fiction but Doug ignored the paintings done for those books. That was definitely a mistake since many of those paintings were quite nice and there was a fairly large market for any paperback cover art, not just science fiction art. Fortunately, a good selection of those paintings became available several years later. But that’s getting ahead of my adventures. Let’s return to early 1977, when I was busy selling Ace science fiction paperback covers to collectors all over the United States. It’s early April and I’ve just heard from a friend of mine who lives on the West Coast. It’s a call that intrigues and excites me. It’s a lead on a fabulous collection, one of the best in the field.

I was friends with a fairly well-known SF writer, Frank R. Frank originally came from Chicago but he had moved to San Francisco years before. He wasn’t an art collector but was a fanatic collector of science fiction and fantasy pulps in mint condition. Frank and I had traded pulps over the years and he was well aware of my interest in science fiction art. That was why he contacted me early in 1977 with word about his friend, Earl, and his art collection.

Earl was another Chicago fan who had been an active SF fan before moving to the West Coasts years ago. Earl had assembled one of the best collections of science fiction art in the country. Now, he had fallen on hard times and was thinking of selling his collection. Frank suggested that I contact Earl about his art before word got around that he was selling his paintings.

I followed up Frank’s tip and contacted Earl. After several letters back and forth, we came to an agreement on most of the art in his collection. Several pieces he valued more than I did, so I didn’t buy those. But I was quite happy with what I did purchase. It was an impressive lot.

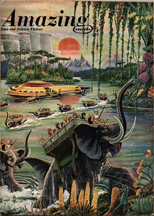

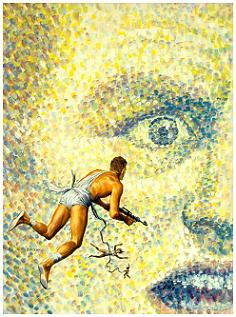

4 – cover paintings by H.W. McCauley (upper left: Imagination, October 1954)

1 – Alex Schomburg cover painting

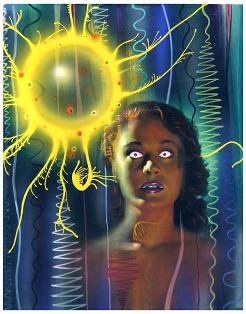

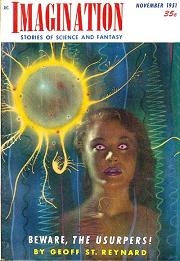

2 – Malcolm Smith cover paintings (upper right: Imagination, November 1951)

2 – Ed Emsh magazine cover paintings

3 – Virgil Finlay black and white illustrations

1 – Kelly Freas black and white illo

1 – Kelly Freas magazine cover painting

1 – Edd Cartier gouache calendar illustration

1 – Kelly Freas hardcover book jacket illustration

It’s impossible to describe the art I bought from Earl other than to say he was a collector with fine taste and he always bought the best of what he was offered. His four McCauley paintings were not just any four paintings by the artist, but four of the very best McCauley paintings. His two Malcolm Smith paintings included one of Smith’s rare photo paintings, where Smith took a large photo and painted on it, to give the picture a degree of realism that could not be achieved otherwise in the early 1950s. His Freas hardcover jacket illustration was perhaps Freas’ best painting ever. Many people thought so. It was truly a fabulous collection and I was extremely fortunate to get a chance to buy it before anyone else. I paid Earl fair prices for the art, prices that reflected the time and the price of original art at the time. Looking back on the price I paid, I have to shake my head in dismay. In those days, how little we valued the great art that helped make science fiction so wonderful. How little value we placed on the magnificent art published in the field. Most of all I think how lucky I was to have collected art in those days!

The secret to assembling a great science fiction collection (of any sort) is to make as many friends as you can in the science fiction field. It doesn’t cost anything to be pleasant and friendly and honest with other people. In the long run, the favors you do for others come back to you many times over. Without a doubt, the one thing I have learned in the course of fifty years of collecting is that good friends are the key to a great collection.

Next Installment: “Meet Marty G.”

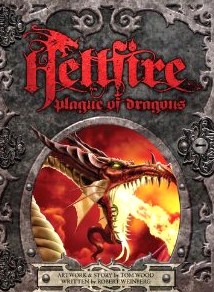

Bob Weinberg is the author of 17 novels, 16 non-fiction books and around a hundred short stories. He’s also edited over 150 anthologies. He owns one of the finest SF/Fantasy original art collections in the world. These days, Bob is busy promoting his new book, Hellfire: Plague of Dragons, done with artist Tom Wood, and serving as editor for Arkham House publishers.

Bob Weinberg is the author of 17 novels, 16 non-fiction books and around a hundred short stories. He’s also edited over 150 anthologies. He owns one of the finest SF/Fantasy original art collections in the world. These days, Bob is busy promoting his new book, Hellfire: Plague of Dragons, done with artist Tom Wood, and serving as editor for Arkham House publishers.