Collecting Fantasy Art #13

Two Great Artists

By Robert Weinberg

Copyright © 2012 by Robert Weinberg

~One~

I had no intention of attending PULP-con in 1990. The convention was always a fun weekend in the middle of the summer but I felt I was much too busy that year to spend time socializing with pulp magazine collectors when I should be working. Earlier that year, I had switched gears in life and started writing professional fiction and non-fiction. I had always dreamed of being a writer and through an unusual set of circumstances, found myself working with a high-powered agent. Together, we had sold a modern horror novel titled The Black Lodge for a good price. I was working under a deadline and was totally dedicated to getting the book written. So PULP-con was out of my plans.

But, talk about the best laid plans of mice and men. The American Bookseller’s Association Convention took place several weekends before the pulp show. The ABA as it was known was a place where major and minor publishers exhibited their books for the next year and promoted their big sale items for the fall. It was also a place where agents met editors and discussed possible books and new contracts. My agent, Lori, was in attendance. With a novel already in the works and certain clauses in the contract making it clear I could not write a novel for another publisher until I turned in the first one, I did not expect to hear from her.

I did. The Saturday of the convention, around mid-afternoon, I got a call from Lori. She sounded breathless and excited. “Didn’t you tell me you have one of the largest Louis L’Amour collections in the world?” she asked.

Correct. L’Amour was a western writer, perhaps the best western writer publishing at the time. He had started as a pulp writer back in the 1930s and I had a huge collection of his pulp magazine stories, along with all of his novels that had been published in paperback. He was one of my very favorite writers and I knew his life story backwards and forwards. I had even ghost-edited two volumes of his short stories that had fallen into public domain for a small New York paperback house.

Feeling somewhat nervous, I admitted to Lori that I had one of the best L’Amour magazine and book collections in the world. And that I knew just about everything there was to know about his life, ranging from triumphs to disasters.

“I was just at the Andrews & MacMeel booth,” Lori told me. “They’re pushing the latest printing of their Stephen King Companion in trade paperback. The book has made them lots and lots of money. So I asked them if they would be interested in a Louis L’Amour Companion. It doesn’t violate your contract if you write a non-fiction book while composing your novel. You’re allowed to do both. The editor I spoke with sounded very interested, so I gave her a week to make an offer. If they don’t come up with the money, some other publisher will. So write me a proposal for the book!”

Which is what I did the rest of the weekend. I put together an outline for a book all about Louis L’Amour and his work. I even contacted some well known fans of L’Amour to contribute articles to my book. Perhaps the most famous was Harlan Ellison who had told me years before that he was a big fan of the western writer. Come Monday and I had a very nice proposal for a book that my agent had invented in a conversation two days earlier.

Which is what I did the rest of the weekend. I put together an outline for a book all about Louis L’Amour and his work. I even contacted some well known fans of L’Amour to contribute articles to my book. Perhaps the most famous was Harlan Ellison who had told me years before that he was a big fan of the western writer. Come Monday and I had a very nice proposal for a book that my agent had invented in a conversation two days earlier.

The editor that Lori spoke with acted fast. She bought the book based on the outline the next day. I was paid a $25,000 advance, which was considered very good money at the time.

Suddenly, attending PULP-con seemed a much better idea. I could write the cost of the entire trip off as a business expense. I could spend most of my time looking for Louis L’Amour pulps. And one of the guests of honor at the show was pulp writer Ryerson Johnson, who had written western adventures for the old magazines from 1930 to the present. I knew “Johnny” and felt certain he would be willing to be interviewed about what it was like working for the pulp magazines. Another good reason to attend the show.

So, since everything was so last minute, I called Rusty Hevelin who was running the event and asked if I could still buy a membership and were there sleeping quarters still available for the weekend. The convention was taking place at a seminary college in Wayne, New Jersey, and there were still rooms available. I made my reservation, bought my plane ticket, and made arrangements to rent a car to drive to Wayne, which was a somewhat out-of-the-way destination in northern New Jersey.

I must admit I had my strong doubts about holding the pulp convention on a college campus. We had done it a number of times in the past, usually using rooms made available to us by the University of Dayton. However, I knew that the attractive graduate student apartments in Dayton were the exception, not the rule, for schools that rented their living quarters during the summer. So, while I was willing to stay at the campus residences provided by the seminary, I mentally reserved the right to move off campus if housing wasn’t what I expected.

Needless to say, the quarters were not lavish. Two people were assigned to each room on the campus. The bed in the room was the size of a cot and a blower in the wall dispensed a stream of cold air on the sleeper. Seeing the arrangement, all I could think of was that this was the way Legionnaires’ disease was spread. None of the rooms had a private bathroom. Instead, there was a community bathroom down the hall. At 25 I might have been willing to stay in such quarters, but not at 45. I checked myself out of the convention rooms and called my mother. Fortunately for me, my mom still lived in a house in Jersey. She was quite happy to welcome her son for an unexpected visit. I stayed at her house all weekend and commuted by car to the pulp show ever day.

I had a good time at the pulp show, especially since I wasn’t staying overnight in the seminary. Even the dealer’s room, which was always the main focus of a pulp convention was warm, as the college had shut off the air conditioning in the main event hall for the summer. Everyone had their own horror story about staying on campus. I suspect it was the worst rated pulp convention ever held.

I got to spend over an hour interviewing Ryerson “Johnny” Johnson. He enjoyed telling me stories about “Hudson River Cowboys,” the nickname given to western pulp writers who had never been beyond the Hudson River. Unfortunately, though I had a wonderful transcript of the interview, it never made its way into the L’Amour book. My editor felt it dwelt too much on the pulps and not enough on Louis. Too much of the pulp material I prepared for the book never made it into the final manuscript.

I did buy a lot of western pulps with L’Amour stories in them. Louis at that time was one of the best selling writers in America. Yet, most pulp fans knew nothing about him or his tremendous sales in paperbacks and hardcover books. Which meant that Louis L’Amour collectibles were being offered to collectors for a few bucks per issue. A few years later, after my book appeared and several collectors wrote articles about Louis and his pulp fiction, those same issues were selling for $10 to $15 per issue.

On Friday night, I made arrangements to meet with my fellow editor and Weird Tales fan, Stefan Dziemianowicz. Stefan and I had worked on a number of anthologies with Marty Greenberg as the book packager. Oddly enough, since Stefan lived in New Jersey and I lived in Chicago, we had never met in person. Instead, when he had an idea for an anthology, he wrote to Marty and me describing his proposal. If the two of us agreed that the idea was a good one, Marty then took the concept out into the field and looked to see if we could sell it somewhere. In the late 1980s, most book store chains had their own line of bargain books – that is, a group of nicely published hardcover volumes inexpensively priced aimed at luring the customer into the shop and spending their money. Two of the many books we put together as “bargain” books included To Sleep, Perchance to Dream…Nightmares and Nursery Crimes. All of our bargain books earned money and I was anxious to meet Stefan in person and talk horror fiction with him.

We went out for pizza and spent a great night talking about favorite authors and favorite stories. It was a fabulous conversation highlighted by a line that caught me off guard and surprised me. “Edd Cartier lives around 20 minutes away from here,” said Stefan. “You should give Dean a call and maybe you could stop in there for a visit?”

It was an idea I would have never thought of but should have. I considered Edd Cartier one of the finest science fiction and fantasy artists ever to work in the science fiction field. I knew that he had left the genre due to a major fight with one of the small publishers in the field in the 1950s and had never returned. Still, for the past several years, both Stefan and I had been in communication with his younger son, Dean, who was anxious to get his father once again recognized as one of the giants of the early 20th century. We had reprinted several of his old illustrations in our anthologies and hoped to use more.

It was an idea I would have never thought of but should have. I considered Edd Cartier one of the finest science fiction and fantasy artists ever to work in the science fiction field. I knew that he had left the genre due to a major fight with one of the small publishers in the field in the 1950s and had never returned. Still, for the past several years, both Stefan and I had been in communication with his younger son, Dean, who was anxious to get his father once again recognized as one of the giants of the early 20th century. We had reprinted several of his old illustrations in our anthologies and hoped to use more.

So, summoning up my courage, I dialed the Cartier family phone number. Dean, who lived with his elderly parents, answered. He sounded genuinely excited to have me come over and visit. Plans were made, directions were given, and my visit was set for the next afternoon.

The Cartier family lived in a small bungalow-style home in the north New Jersey suburbs. I arrived there around 2 pm and was met at the door by Dean and his father, Edd. Though I had never seen any photos of the artist, I had no trouble recognizing him. He was short, with expressive features, a clean shaven chin, and a full head of hair. He had a warm smile. Dean, who was in his early 30s, was slender built but had that same warmth of character. The two men welcomed me to their house, had me come in, and introduced me to Mrs. Cartier.

The next hour I spent in heaven, examining the Cartier artwork on the walls. The living room contained the originals for The Cometeers and Masters of Time. Dean’s bedroom held one of the true Cartier masterpieces, the cover illustration done for the 1948 Unknown Worlds revival. Needless to say, the original looked much better in person. Along with the actual painting, Dean had four sketches his father had submitted for the editors to make their choice.

Downstairs, in the basement, Dean had positioned a very cute western illustration with an old cowboy with a gigantic handlebar moustache confronting a huge rattle snake. The art had appeared in The Saturday Evening Post. This piece had been done when Cartier shared an artist studio with Nick Eggenhoffer. With Cartier only a few inches over five feet tall, and Eggenhoffer, one of the tallest artists around standing well over six feet tall, the pair was known for years as the “Mutt and Jeff” of the art field.

Best of all, I was able to speak with Edd Cartier one-on-one. There was nobody there to interrupt me when I asked questions, no one to censor the responses I got. We talked about John W. Campbell, Jr. and we talked about L. Ron Hubbard. He told me which artists he admired most and which publishers had treated him badly. It was an honest conversation, and one that I never forgot.

Best of all, I was able to speak with Edd Cartier one-on-one. There was nobody there to interrupt me when I asked questions, no one to censor the responses I got. We talked about John W. Campbell, Jr. and we talked about L. Ron Hubbard. He told me which artists he admired most and which publishers had treated him badly. It was an honest conversation, and one that I never forgot.

After viewing a few more interesting pieces of memorabilia, we retired to the living room where Dean promised to “turn my hair white.” I had no idea exactly what he meant, but, when his father pulled up a chair next to mine and Dean came down from the second floor of the house carrying what had to be more than fifty art boards, I started to get excited.

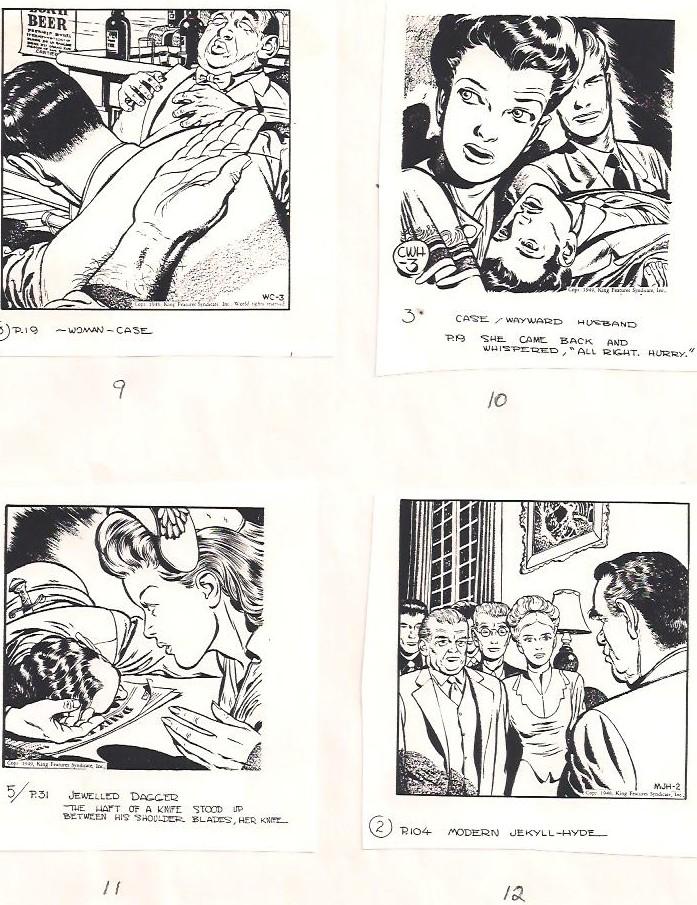

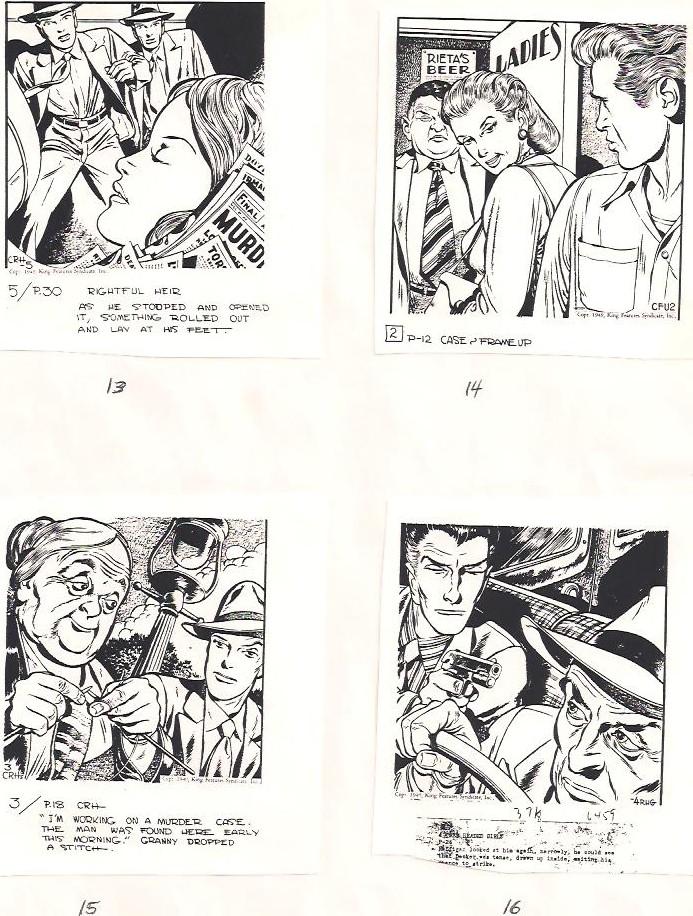

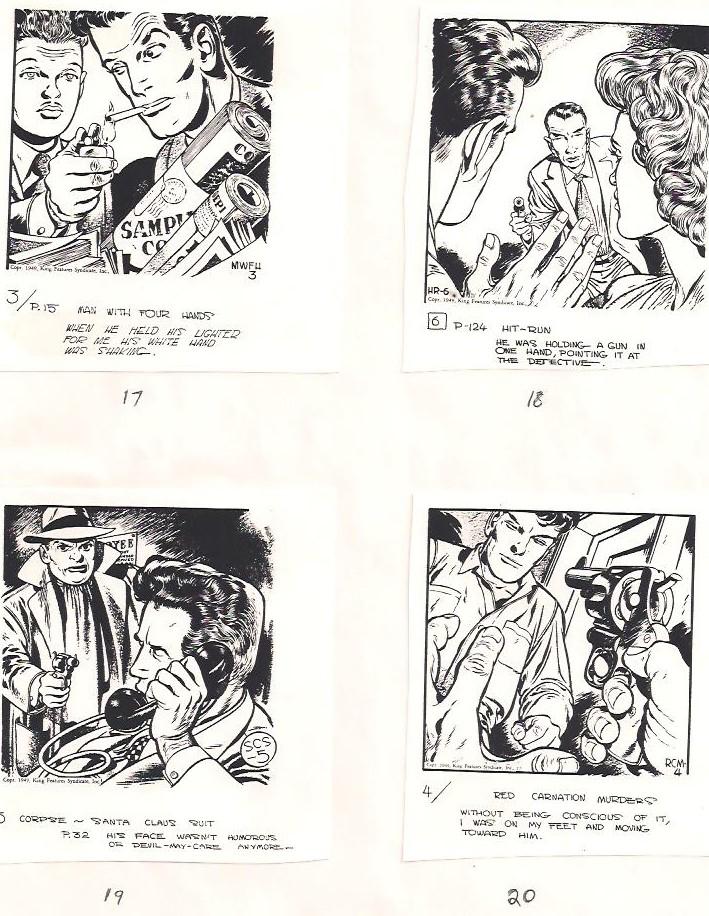

Each board contained one original Edd Cartier illustration. There were two sizes of board – 16×24 and 11×14. The larger size boards contained Cartier’s originals from before World War II, most of them done for Unknown and Unknown Worlds magazine. The smaller boards featured art done after the 2nd World War, mostly for Astounding SF, as well as a few off-trail magazines like Other Worlds and Planet Stories. The art ranged from spectacular to incredible. While I did get a chance to look at it all, none of the pieces were for sale. Dean and his brother wanted to start an Edd Cartier museum and felt their father’s stash of originals would serve as a perfect bedrock for any exhibit. Much as I wanted a piece – several in fact – I couldn’t argue with their logic.

Late in the afternoon, I said goodbye to the Cartier family. I am not a person easily star-struck, but in meeting Edd Cartier, one of the greatest of all fantasy artists, I was impressed. Sometimes life is incredible!

~Two~

Now, after my visit to the Cartier family, I reached the realization that I most likely would never see as astonishing an art collection from one artist at one time. Most pulp artists had never asked for their art to be returned and most publishers, as a matter of principle, didn’t send it back. Cartier, like Virgil Finlay, had been one of the very smart few, who had specifically asked for his art to be returned. A vast majority of it had not been. The publishers considered the originals to be their property. I considered myself extremely lucky to have seen the Cartier cache. I doubted I would ever see another.

Ten years slipped by. Lots of fine artwork bought and sold. Not many surprises, though plenty of good deals. It was a quiet Sunday, June 17, and Phyllis and I were reading the Sunday newspapers. We did not expect anything unusual to happen. So much for ESP!

We got three papers every day – The Chicago Sun Times, The Chicago Tribune, and the Chicago Southtown Economist. Of the three, the Economist had the least important news, but it did cover the south suburbs where we lived. Phyllis liked to read it first.

“Hey, did you see this?” my wife asked, her voice excited.

“No,” I replied, wondering what had brought about this sudden outburst. “See what?”

Bursting out of the dining room, Phyllis marched triumphantly over to the sofa where I was lounging and thrust a section of newspaper in my face. “This!”

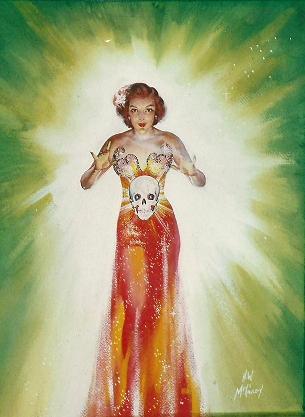

I looked at the double-page spread article, illustrated with many photographs and had to admit that the story was a knockout. Simply titled “Harold,” the piece was a brief biographical sketch of Chicago artist, Harold McCauley, who had been born in Chicago in 1904. Harold W. McCauley attended both the Art Institute of Chicago and the American Academy of Art. He studied under the famed artist, Haddon Sundblom, and he remained a close friend of Sundblom (the artist who created the Coca-Cola Santa Claus) for many years afterward. A large Sundblom painting, a gift from the artist, hung in the McCauley parlor. It was through Sundblom that McCauley got his first work, doing illustration art, which caught the attention of the art director at magazine publisher, Ziff-Davis, who hired McCauley soon afterward.

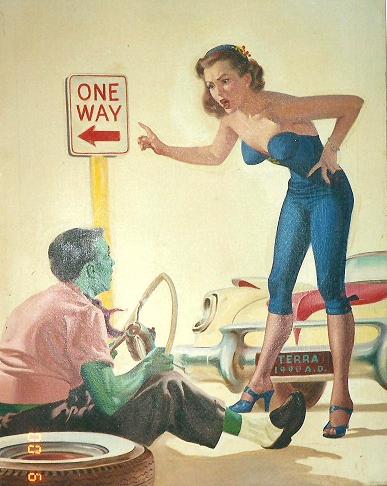

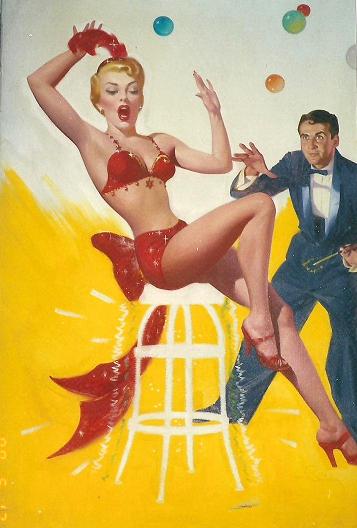

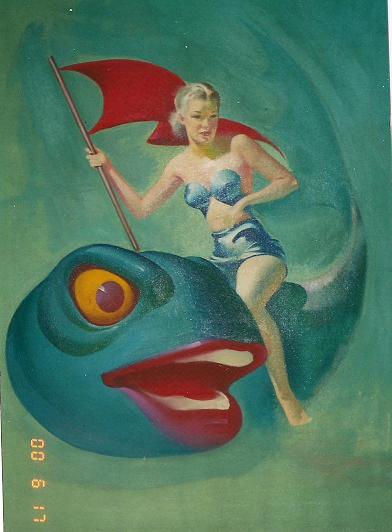

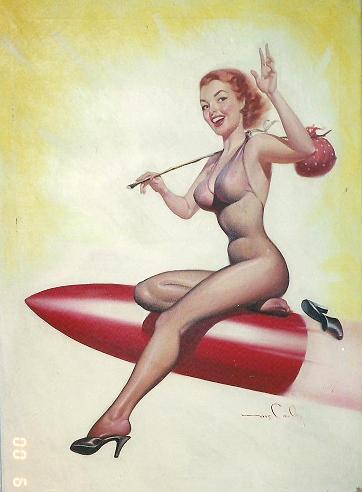

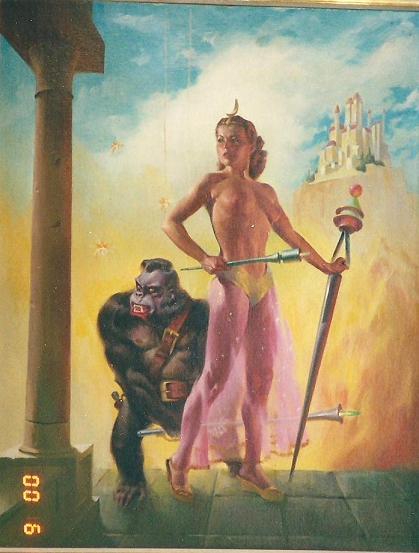

After working as a staff artist for Ziff-Davis for many years, McCauley followed William Hamling to Imagination, where, free of the restraints of illustrating specific stories, he painted some of the finest science fiction pinup artwork ever to appear in the field. McCauley later married one of his model’s, Grace. When Hamling left for California, McCauley moved his family to Florida, where he did business illustrations and portraits until his death from a heart attack in 1977.

After working as a staff artist for Ziff-Davis for many years, McCauley followed William Hamling to Imagination, where, free of the restraints of illustrating specific stories, he painted some of the finest science fiction pinup artwork ever to appear in the field. McCauley later married one of his model’s, Grace. When Hamling left for California, McCauley moved his family to Florida, where he did business illustrations and portraits until his death from a heart attack in 1977.

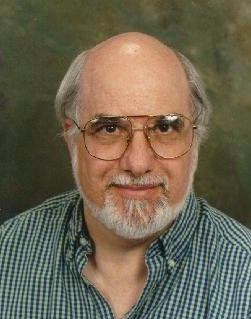

McCauley, a confirmed bachelor most of his life, met Grace when she came to his house on a modeling assignment. She is the stunning subject of many of his best cover paintings. Oddly enough, McCauley is even more recognizable than his wife. McCauley had a wide face, with sparkling eyes and an engaging smile, and Haddon Sundblom often used him as a model for his advertising art. McCauley stares back at people eating cereal every day, as his is the face beneath a powdered wig that Sundblom used for the smiling Quaker on the Quaker Oats box. During the course of writing my Biographical Dictionary, I had never been able to track down much info about McCauley. Nor had I found any of his relatives. Now, I discovered reading the article, they lived about twenty blocks from my house!

After a round of phone calls, my wife and I went to the McCauley exhibit where we met Kim McCauley, one of McCauley’s daughters. The McCauleys had moved back to Chicago just a few years before, and were planning to return to Florida soon after the exhibit. So, I was in luck to catch them during their brief sojourn in Illinois. I interviewed Kim about her father several times. I also spoke to a second sister. A third sibling, a son, no longer lived with the family. McCauley’s wife, Grace, his most famous model, appearing on numerous pin-up covers done for Imagination I never got to meet. She refused to come out and talk whenever I came by for an interview because she no longer looked liked the model in the paintings.

~Next Time~

Remembering Jerry

Text and art copyright © 2012 by Robert Weinberg and Tangent Online.

All Rights Reserved.