Collecting Fantasy Art #12

Secrets of New Jersey – Part 2

Three Unusual Trips

By Robert Weinberg

Copyright © 2012 by Robert Weinberg

~ One ~

Sam Moskowitz told me this story about visiting Virgil Finlay in 1970. It demonstrated just how honest Sam was, and how miserable the original art field once was in regards to actual prices paid by collectors for illustrations. Once upon a time, you didn’t need much money to build an original art collection. As demonstrated by this adventure. Imagine how different the collecting market would have been if Sam had acted on his impulses.

In early spring, 1970, Sam arranged with Robert Lowndes, the publisher of The Magazine of Horror to feature a Finlay black and white original as the cover illustration for each issue of the magazine. The amount of money Finlay received wasn’t mentioned but Lowndes didn’t have much of a budget for his small magazine. Still, any money was better than no money and Finlay was in poor health at the time and needed the cash.

In early spring, 1970, Sam arranged with Robert Lowndes, the publisher of The Magazine of Horror to feature a Finlay black and white original as the cover illustration for each issue of the magazine. The amount of money Finlay received wasn’t mentioned but Lowndes didn’t have much of a budget for his small magazine. Still, any money was better than no money and Finlay was in poor health at the time and needed the cash.

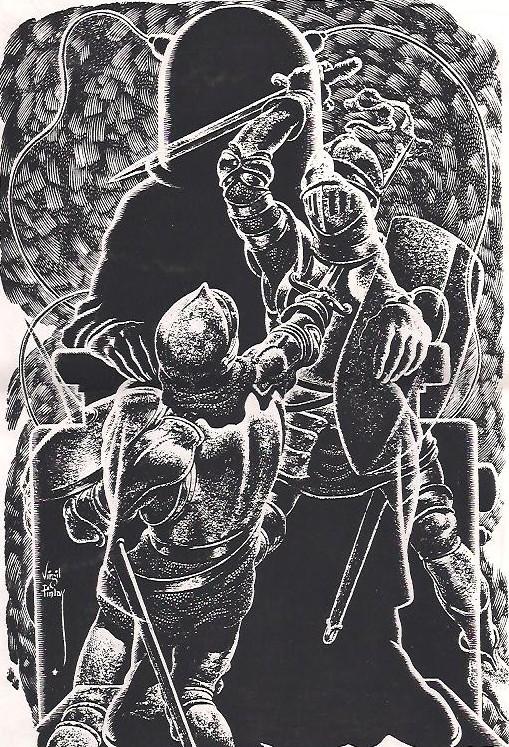

Once the deal was made with Lowndes, Sam drove to Long Island to meet with Finlay and select those illustrations that would be used for the covers. Unlike most artists who worked for the pulps and the digest magazines, Finlay had always asked that the publishers return his artwork. According to Sam, Finlay had several thousand originals in his possession. It wasn’t very hard to pick out a dozen or so stunning pieces to serve as cover illustrations. It was afterwards that things got interesting.

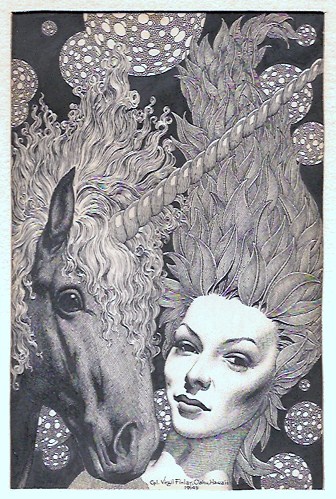

Surrounded by thousands of Finlay originals, Sam couldn’t help but ask if he could buy a few of his favorite pieces. Finlay was more than happy to assist Sam finding pieces he wanted. Chief among these was the illustration of a girl and unicorn that Finlay had composed during World War II and that had served as the inspiration for the C.L. Moore/Henry Kuttner story, “Daemon.” Sam had always considered that illustration to be Finlay’s finest, and he was thrilled to obtain it from the artist for the incredible price of $25. All in all, Sam bought a half-dozen originals from Finlay that afternoon, spending a little more than a hundred dollars. It wasn’t much but Finlay was happy to get it.

Still, Sam felt certain that if he had asked Finlay if he would sell ALL of his originals for a set price – something like $2 each – the artist would have agreed immediately – with enthusiasm! That offer of a few thousand dollars, which Sam could have afforded without much trouble, would have purchased all of the original illustrations that Finlay owned. And the artist would have been so happy to make the deal he would have helped Sam carry the art out to the car.

Now, the deal never happened and Sam had no real proof other than a feeling that Finlay would have said yes. However, several months later, the artist was diagnosed with cancer and needed lots of cash immediately. He made a deal with collector and fan, Gerry de la Ree, to sell a great many of his originals. Prices were set extremely low, with most pieces selling for under $20 each, suggesting that Gerry hardly paid anything for the illustrations. Exactly what Sam claimed, pretty much confirming his story. Leaving me to wonder what would have happened if Sam Moskowitz had bought Virgil Finlay’s original art archive? Would hundreds of illustrations been offered for sale to collectors, cheap? Or would Sam have kept everything and not sold the originals for years? Thinking about it raises some fascinating questions. It’s a mystery that has to be classified as a Secret of New Jersey.

~ Two ~

The magic name, “Roy Krenkel,” drew me back to the wilds of New Jersey in the scorching hot summer of 1988. I returned to the state based on an old rumor and a modern promise of some worthwhile business. While the deal didn’t work out exactly as I hoped or planned, it didn’t crash and burn in disaster either. If anything, I found myself juggling triumph and disappointment at the same time with one hand tied behind my back and a bandana covering my eyes. Such is life, one realizes, dealing in rare art.

The situation was fairly simple. Well known fantasy author, anthologist and collector, Lin C. (photo at right, 1978) had been living in Montclair, New Jersey ever since he had split from his wife back around 1980. Lin and I were long-term acquaintances. I had known him for nearly twenty years. He was a famous fantasy fan and Lovecraft scholar and he collected original art. We had never traded originals but had discussed the possibility more than once. He and I both liked the pen-and-ink work done by Roy Krenkel, especially the work he had done illustrating our favorite author, Robert E. Howard. A fan growing up in the 1940s and 1950s, Lin knew Hannes Bok and owned a number of early Bok originals. Like most older fan- collectors, Lin liked to talk about swapping art, but he rarely ever completed a deal. Old fans just couldn’t let go of their treasures, no matter how good the trade was.

The situation was fairly simple. Well known fantasy author, anthologist and collector, Lin C. (photo at right, 1978) had been living in Montclair, New Jersey ever since he had split from his wife back around 1980. Lin and I were long-term acquaintances. I had known him for nearly twenty years. He was a famous fantasy fan and Lovecraft scholar and he collected original art. We had never traded originals but had discussed the possibility more than once. He and I both liked the pen-and-ink work done by Roy Krenkel, especially the work he had done illustrating our favorite author, Robert E. Howard. A fan growing up in the 1940s and 1950s, Lin knew Hannes Bok and owned a number of early Bok originals. Like most older fan- collectors, Lin liked to talk about swapping art, but he rarely ever completed a deal. Old fans just couldn’t let go of their treasures, no matter how good the trade was.

Thus, I was well aware of the size and scope of Lin C’s art collection but I never actually expected to get anything from it. What I wanted most was the cover painting for the Robert E. Howard paperback of King Kull. Lin had never offered this piece to me, but he had edited the book and he was rumored to own the cover painting. A Krenkel masterpiece, it was my number one art want. The other problem dealing with Lin C. was that he was extremely unreliable. That was because Lin was involved in twice as many projects as he could handle, all at the same time. In the 1970s, Lin wrote novels, edited anthologies, and nurtured new authors in the fantasy field. It was all very exciting, but confusing as well. Money was spent but not always accounted for properly. Bills were not paid. Lots of people blamed Lin C. for their problems. Not very reliable, his finances were a mess.

Worse, life underwent changes unexpectedly and oftentimes not exactly the way you expected. Lin C. smoked. It was a bad habit and every one of his friends warned him that smoking was a one-way ticket to the graveyard, but he never listened. He should have. He really should have. Lin developed cancer of the lip in 1985. Not good at facing disaster, he waited nearly too long to get help. Curing him of cancer required removal of most of his jaw, which was done in a VA hospital, leaving Lin horribly disfigured. The next few years of his life, Lin wore a mask over what remained of his face and slowly but surely drank himself to death. He died on February 7, 1988.

Worse, life underwent changes unexpectedly and oftentimes not exactly the way you expected. Lin C. smoked. It was a bad habit and every one of his friends warned him that smoking was a one-way ticket to the graveyard, but he never listened. He should have. He really should have. Lin developed cancer of the lip in 1985. Not good at facing disaster, he waited nearly too long to get help. Curing him of cancer required removal of most of his jaw, which was done in a VA hospital, leaving Lin horribly disfigured. The next few years of his life, Lin wore a mask over what remained of his face and slowly but surely drank himself to death. He died on February 7, 1988.

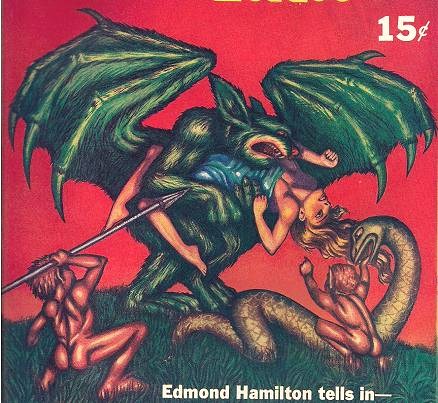

(Cover at left by Hannes Bok for Weird Tales, 1940)

Needless to say, Lin didn’t leave a will. However, he was smart enough to appoint his close friend and long-time fan of his fiction, Bob P. as Executor of his Estate. It was probably the best decision Lin made in the last few years of his life. Bob P. was a well-known fan publisher who was notoriously honest. If anyone could straighten out the mass of debts Lin C. left when he died, it was Bob P.

Which was exactly what Bob P. proceeded to do for the next six months after Lin C’s death. He deposited wayward checks, collected unpaid debts, paid forgotten bills, settled old accounts. Little by little, using the remnants of money left by Lin C, Bob P. put the dead author’s life in order.

Late summer 1988. It was a hot, humid season and I was quite happy that I had no places to go. My mail-order business was doing terrific business and I was quite satisfied to stay at home and manage the paperwork that needed to be done. My wife was busy working for the business and taking care of our son, Matt. We had one full time employee, Steve, who drove a dozen miles or so to get to work each morning. Living, as the song said, was easy. Or so it was, until Bob P. called.

Late summer 1988. It was a hot, humid season and I was quite happy that I had no places to go. My mail-order business was doing terrific business and I was quite satisfied to stay at home and manage the paperwork that needed to be done. My wife was busy working for the business and taking care of our son, Matt. We had one full time employee, Steve, who drove a dozen miles or so to get to work each morning. Living, as the song said, was easy. Or so it was, until Bob P. called.

Truthfully, I never expected to hear from him. When Lin C. died, I assumed his art collection died with him, shipped off to those people to whom he owed the most money. Since Lin had never sent me a list of what he owned, I just assumed that it hadn’t been as much as I had once believed and that it had disappeared like most collectibles do when a well-known fan passes on. Moreover, with Lin’s notorious drinking problem, I assumed that most if not all of his valuables had been bartered off years earlier for spending money to pay for beer and shots. More than a few fabulous collections had vanished paying for drinks for alcoholic art accumulators.

Bob’s call came on a Thursday afternoon. It was fairly short and to the point. He wanted to know if I was still interested in original art from Lin’s collection. I asked if the Roy Krenkel cover painting for King Kull was still there. Bob said he was pretty sure it was. Then I was still interested in the art, I answered. If I was, Bob told me, then I better get to Montclair, New Jersey by the weekend. The landlord of Lin’s apartment was preparing to throw out all of Lin’s possessions, including his original art, that coming Monday. Bob was willing to sell to me any originals I wanted at a bargain price assuming I could rescue the art and misc. pulps from the dumpster.

Evidently, Bob had ignored Lin’s possessions in his apartment while settling his outstanding bills. He had paid all of the writer’s debts but had never settled a bill with the building’s landlord. Now, the building’s owner wanted to rent out the apartment to someone new. That meant all of Lin’s old possessions needed to be disposed of by that following Monday.

Evidently, Bob had ignored Lin’s possessions in his apartment while settling his outstanding bills. He had paid all of the writer’s debts but had never settled a bill with the building’s landlord. Now, the building’s owner wanted to rent out the apartment to someone new. That meant all of Lin’s old possessions needed to be disposed of by that following Monday.

I wanted that Krenkel painting. It was one of his finest creations, painted for the Lancer Book paperback collection of Robert E. Howard’s “King Kull” stories. The notion of it being tossed away in the garbage made me ill. The opportunity to obtain the painting for a small amount of cash was too great to pass up. I had to get to Lin C.’s apartment in New Jersey before the landlord trashed the premises and threw away all of the original art. I had to!

Flying to Newark, renting a car, and bringing the painting back on an airplane would have been near impossible. Besides, knowing that one painting was there had me wondering if there might not be some more artwork? The pieces might be too big to carry on board an airplane. Plus, Bob P. had mentioned a bunch of pulps and rare hardcover books as well on the property. This situation called for a full-fledged rescue. Traveling by plane was not feasible.

Friday morning, bright and early, Steve and I set off for New Jersey in my station wagon. Hoping that I was heading for a major score, I called my mother, who still lived in our old home in Jersey and told her I would be visiting for a night. I carried hundreds of dollars in small bills in my pockets. I was ready for one painting or a dozen.

(Covers above right by Josh Kirby for Prince of Scorpio and Suns of Scorpio, respectively.)

The trip from Chicago to Montclair, New Jersey, in blazing 100 degree heat took thirteen hours of highway driving. Knowing we had to be in the Garden State by Sunday at the latest, we drove all day Friday till we reached the middle of Pennsylvania, where we stopped for the night at a roadside motel. The constant bright sun while driving made the trip difficult but not impossible. What kept me going was the thought that waiting for me on the end of the drive was the Krenkel painting for King Kull. The painting was a prize well worth fighting for. I had no idea what Bob P. wanted for the original, but I was willing to pay any fair price to buy it.

We checked out of the motel the next morning and drove straight east for Montclair, New Jersey. We arrived in mid-afternoon, with the sun high in the sky and the temperature hovering around triple digits. It was hot and very humid and I was anxious to see some art. We were at Lin C.’s apartment building but Bob P. wasn’t there. He was quite intelligently waiting in his air conditioned home blocks away. We called him and waited. And waited some more as it took time for him to get there.

When he did arrive, he opened a pair of outside doors leading down into the cellar. I had to descend the cellar stairs slowly, making sure that I didn’t fall into the basement storage section of the apartment building. Fortunately, Bob P. brought a flashlight because the lights in the cellar weren’t working. As I descended, I kept a careful eye on my surroundings. At the same time, I listened to what Bob P. told me. The news wasn’t good. He had scoured the apartment from top to bottom but he had not been able to find the Krenkel painting. Unless it was hidden somewhere, and he had no idea where, the painting was no longer there. He remembered it hanging in Lin’s apartment as did other of his friends, but evidently the author must have sold it when he grew ill. Knowing how much I wanted that painting, Bob felt terrible. He hoped I wouldn’t consider the whole trip a failure.

Hearing the news half-way down into the basement, with the flashlight shining on a painting perched on an easel three feet further down into the cellar, I had to admit that while I was disappointed, I could manage to deal with my sorrow. Especially since I recognized the painting below as a Virgil Finlay original from Super Science magazine from 1942 (cover at right). And, I could see in the fringe of the flashlight beam, a Hannes Bok original painting from Weird Tales in 1940.

Hearing the news half-way down into the basement, with the flashlight shining on a painting perched on an easel three feet further down into the cellar, I had to admit that while I was disappointed, I could manage to deal with my sorrow. Especially since I recognized the painting below as a Virgil Finlay original from Super Science magazine from 1942 (cover at right). And, I could see in the fringe of the flashlight beam, a Hannes Bok original painting from Weird Tales in 1940.

It took me around fifteen minutes to get situated on the cellar floor. Recognizing the Lin C. material wasn’t difficult. The paintings were all in cheap black metal frames. Moreover, the landlord of the building had marked them all with prices for a garage sale. The Finlay painting was a quarter, the Bok painting which was three feet wide and three feet high was fifty cents. Several small paintings by Josh Kirby were priced at a dime.

There were dozens of originals in the Lin C. collection that I bought from Bob P. that afternoon. All of them had been tagged and priced for the garage sale, so I saved them from a terrible fate. Along with the stacks of framed artwork, there were piles of books and Weird Tales pulp magazines. They too had been scheduled for the spectacular garage sale so we rescued them for reasonable prices paid to the estate. The wheeling and dealing lasted till night time. When it was all done, Steve and I and a near full station wagon of framed art and old pulp magazines drove off heading for my mother’s house.

I remember arriving there shortly after 9 p.m. that night. My mother had all the lights on, expecting me. Steve and I unloaded the magazines and the paintings as quickly as possible. We had no desire to annoy the neighbors with the noise. Then we ordered a pizza and began to work.

The frames on the art were old and twisted and there was dark mold growing beneath the metal. We carefully removed the frames one after another and wiped down the art with some old rags. It was slow going but we had the whole night to get the job done. Actually, we finished around midnight. The originals looked fine and the metal frames filled two garbage cans. The pulps wiped clean of dust and dirt looked fine.

I bought the Lin C. collection in 1988, nearly a quarter of a century ago. Included in the group was a Finlay cover from Super Science Stories from 1942; there was a Bok painting from the May 1940 Weird Tales for Edmond Hamilton’s story, “The City in the Sea”; there were four Josh Kirby DAW paperback covers including a Year’s Best Fantasy Stories edited by Lin C.; a cover painting (at left) for the novel, Tara of the Twilight, written by Lin C.; and much, much more. I foolishly did not make up a list of everything I bought in that collection, which is why many years later, I cannot recall exactly what remains on my walls courtesy of Lin C.

I bought the Lin C. collection in 1988, nearly a quarter of a century ago. Included in the group was a Finlay cover from Super Science Stories from 1942; there was a Bok painting from the May 1940 Weird Tales for Edmond Hamilton’s story, “The City in the Sea”; there were four Josh Kirby DAW paperback covers including a Year’s Best Fantasy Stories edited by Lin C.; a cover painting (at left) for the novel, Tara of the Twilight, written by Lin C.; and much, much more. I foolishly did not make up a list of everything I bought in that collection, which is why many years later, I cannot recall exactly what remains on my walls courtesy of Lin C.

I do remember it was a spectacular addition to my collection. And I classified the selection as another Secret of New Jersey.

~ Three ~

The following adventure has no direct tie-in with New Jersey, yet somehow, I nonetheless think of it as one of the Secrets of New Jersey. Perhaps because the personality of the main character involved in this routine reminds me so much of New Jersey though he is a native of New York City. Or perhaps because the events involved are so New Jersey in nature they belong nowhere else. Whatever, let the story unfold.

I’ve mentioned Bob Lesser more than once in these memoirs. Originally, he was a Disney collector who lived in New York City who accumulated the most spectacular Disney memorabilia collection ever assembled. He also put together the finest toy robot collection in the world. While doing this, he stumbled across several pulp magazine cover paintings and had fallen in love with pulp cover artwork. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, he put the word out in the collecting market that he was interested in buying pulp cover originals and would pay top dollar for pieces he liked.

I sold Bob Lesser a science fiction pulp cover from Amazing Stories in 1973. It was a difficult decision but I needed the money. He visited the apartment Phyllis and I rented the second year of our marriage in 1974 to look at our small pulp cover painting collection. It was there that he told us he was getting out of Disney and toy robot collecting and going to concentrate entirely on pulp magazine covers for the rest of his life. We didn’t know whether to believe him or not, though he did offer us a nice price for our original Doc Savage pulp cover, which we refused. It didn’t matter much if he changed hobbies, we decided. We wouldn’t sell Lesser many paintings and doubted that most science fiction or pulp collectors would sell him any either. He would soon learn that collecting original pulp art required years of making contacts and learning all about pulp artists. You had to be a fan of pulp art before you were accepted by pulp art collectors as one of their own. We felt that collecting pulp cover art required enthusiasm and skill that Bob Lesser didn’t possess.

Fortunately for us, we didn’t place a bet on our conclusion. Nor did we tell many of our friends what we believed. Not only did Bob Lesser prove us wrong, he proved us incredibly wrong. After viewing our small collection of pulp magazine cover paintings, Lesser went out into the art market and assembled the finest pulp magazine original art collection ever accumulated by a single buyer. Using techniques he developed putting together his Disney and robot collections, he assembled an unmatched pulp art library with ease. He made every long-time collector in the field look like a fool. Including me.

What Lesser did was put together a list of names of collectors who owned original art, ranging from people who had only one or two paintings, to long-time fans who owned dozens of pieces. Then, he traveled around the country, stopping in to see those collectors in person, and offering them fabulous amounts of cash money for their artwork. Lesser became famous in the Science Fiction field as the man who walked on $100 bills. That nickname arose from the fact that Lesser carried thousands of dollars in hundreds on his person in cash, with which he would offer to buy paintings. Careful of being hijacked or robbed, Lesser kept the hundreds safely packed in his shoes, removing the bills whenever he needed the money.

Lesser didn’t offer a hundred dollars or two hundred dollars more than what a painting was worth. He offered prices that were higher than pulp fans ever imagined for their treasures. Mr. Lesser valued the paintings at ten or fifteen times what the average collector thought the art was worth. And he was willing to pay that amount to get the original.

Lesser didn’t merely pay double or triple what it was worth. If he desired a piece, the sky was the limit. He changed the value of pulp artwork almost instantly by himself. As mentioned earlier, Lesser raided Forrest J Ackerman’s collection of original Frank R. Paul art for Wonder Stories. Ackerman had owned the early Paul artwork for decades and swore he would never let any of them go. That was before Bob Lesser offered to pay him more than $10,000 per painting. Suddenly, 4sJ was no longer that attached to the art. Not when the selling price was in five figures.

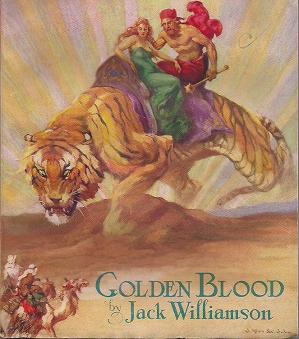

Then there was the time that Bob Lesser saw the art for the 1933 Weird Tales serial, “Golden Blood.” It was reproduced on the cover of the Jack Williamson book, but the painting was listed as belonging to old time fan, Russ Swanson. Lesser tracked Swanson down only to discover Swanson had given the painting to his ex-wife. Lesser convinced Swanson to get the painting back, paying him a five-figure sum for the artwork. As with Forry Ackerman, money talked. It shouted.

Lesser wasn’t subtle, but he got results. He used his money like a magic wand, and with each wave it produced incredible results. Within a year since he began collecting, Bob Lesser was famous. No one sold a piece of original science fiction or pulp art without consulting him first, making sure he did not want the piece and was willing to pay some enormous price for it.

Soon, very soon, prices for art jumped enormously. Numerous art dealers argued that if Lesser was willing to pay high prices for old pulp art, then the originals were worth the amount he was buying them for. So, they raised the prices of the collectibles they had to Bob Lesser levels. And that was that.

The sharp rise in pulp art prices didn’t go unnoticed by the paperback art collectors. If a Shadow or Doc Savage cover painting sold for $12,000 to $15,000 each, then why shouldn’t an Ed Emsh Ace paperback cover painting, with much more detail, sell for nearly that same amount? If not $12,000 then $8,000 to $10,000, with some exceptional pieces pricing higher. There wasn’t much arguing, and suddenly paperback art prices were up in the multiple thousands. What I sold for $150 in 1977 was now $15,000 in 1993. Prices had risen 100 times the original cost in approximately fifteen years!

In 1998, Lois Gresh and I collaborated on a computer thriller, The Termination Node. Twice during the writing of the book, we were flown by our publisher, Random House, to New York City to discuss the plot of the story and advance publicity for the book. The second time was early in the winter of 1998 and Lois brought her family with her. During the time we were not talking with our editors, we traveled around the city seeing the sights.

The second day there, we visited the Empire State Building. Afterwards, Lois’s family was scheduled to see Rockefeller Center. I had a different idea. I knew Bob Lesser lived in an apartment only a few blocks away from the Empire State Building. I decided to call him and see if I could visit. After all, I had never seen all of his paintings and this might be my only chance.

I got Lesser on the phone and he was quite agreeable to my visit. When Lois heard my plans, she insisted on coming along. She had met Bob Lesser at numerous science fiction conventions over the years and knew all about his fabulous collection. Like me, she was thrilled with the thought of seeing it.

Splitting up with Lois’ family, we headed north looking for Bob Lesser’s apartment. It took us around ten minutes to find the building. To our surprise, Lesser lived in a narrow four-flat next to a grocery store. It was not the modern luxury castle we both had imagined. We entered the narrow wood hallway and rang the bell.

Bob popped out of a nearby doorway and welcomed us to his place. He owned his apartment and several years before had bought the other apartment on the first floor. He knocked out the wall separating the two units, and thus the entire first floor was one gigantic apartment that was his. And it was filled to the brim with paintings.

Pulp paintings were painted large size. Most of the artists during the pulp era preferred working oil on canvas. Their canvas was usually two feet by three feet. Oftentimes, when Lesser got the painting framed, he also included the original pulp magazine in the frame to compare with the original art. Such displays were usually three feet squre, the extra space being there for the pulp.

Lesser’s apartment was not large. The front doorway opened into a narrow hallway leading back. There was a full bathroom across from the front door. The hall led back several feet to a small kitchenette that was attached to a small dining room. Lesser used the dining room as his bedroom, with a narrow cot near the wall for sleeping. On the right of the dining room was a second room, filled with paintings and robots and toys. Most likely this had been a bedroom or the living room. Beyond this room were a number of other small rooms that I believe had once been the other apartment on the floor. All of those rooms had been gutted of decoration and purpose and instead were filled with pulps and paintings. They served as Lesser’s warehouse.

Lesser had decorated his entire apartment with framed paintings. There were paintings on all the walls. There were paintings hanging on the outer doors of all the rooms, including the bathroom. It took me several minutes of hunting to find the door knob for the bathroom located between two paintings. There were stacks of paintings leaning up against the cot, and there were paintings, in frames, screwed on tight to the ceiling. The entire dining room ceiling was covered with pulp hero artwork. Bob Lesser could study the Shadow pulp hero while drifting off to sleep. There was art everywhere you looked.

I had never seen so much pulp artwork in one place and I had to admit that there was almost too much to see and absorb. The middle room, which was filled with stacks of paintings ten or fifteen deep leaning against the walls fascinated me. Not only were there paintings everywhere, most of them on the floor, leaning against a wall, but there were toys and robots mixed in. Bob Lesser had sold his robot collection but evidently had kept more than a few reminders. There were robots everywhere in the spare room.

I had never seen so much pulp artwork in one place and I had to admit that there was almost too much to see and absorb. The middle room, which was filled with stacks of paintings ten or fifteen deep leaning against the walls fascinated me. Not only were there paintings everywhere, most of them on the floor, leaning against a wall, but there were toys and robots mixed in. Bob Lesser had sold his robot collection but evidently had kept more than a few reminders. There were robots everywhere in the spare room.

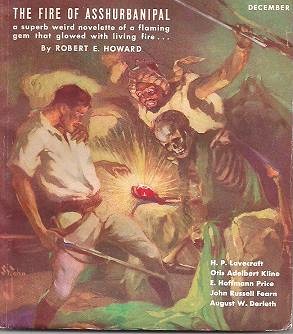

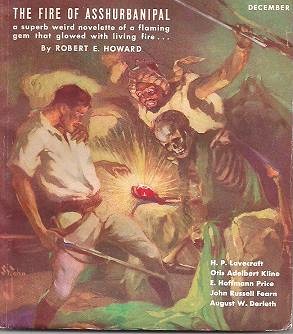

I was casually browsing through the art in that room when I spotted a classic painting published as a cover for Weird Tales magazine. The art was by J. Allen St. John, and it illustrated the Robert E. Howard short story, “The Fire of Asshurbanipal.” It had been published in the December 1936 issue of the magazine and had always been one of my favorite covers. The piece showed two adventurers discovering a skeleton sitting on a stone throne and holding in one outstretched hand a gigantic flaming ruby, the “Fire” of the title.

Now, unfortunately, the painting was wedged up against a tall cabinet in the middle room and there was a huge 5-foot tall giant robot pushed against it, holding it in place and blocking my vision of the bottom half of the painting. That was the bottom half of this fabulous painting including the image of the skeleton holding the jewel. As a fanatical collector of Weird Tales, I was determined to see the entire painting, perhaps the 2nd finest St. John painting ever done.

So, I reached out with both hands and tried to move the giant robot. I tugged with both hands. It didn’t move. I pulled harder. It still refused to move. Peering over the robot’s shoulder, I could just see the flash of the fire jewel in the painting. I would not give up! I wrenched with all my strength at the robot’s arms. It shifted an inch or two. Encouraged, I wrenched harder. And lost my balance.

I fell backward, releasing my grip on the toy robot, my arms and legs swinging wildly for an instant. That’s when I suddenly remembered that I was surrounded by hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of original art. I literally snapped my heels together and slapped my hands to my hips. Just in time, I realized as I looked around. I had stumbled a foot back from the giant robot. A few inches from my right foot was a stack of paintings leaning against a wall. All of them were oil on canvas and none of them were protected by glass. Top of the stack was J. Allen St. John’s cover painting for Golden Blood, created for the March 1933 issue of Weird Tales and my choice as his finest work. My shoe hadn’t gone through the canvas, but it hadn’t missed by much. I had almost put a six-inch hole through one of the greatest pulp paintings ever published. It was a chilling thought.

I fell backward, releasing my grip on the toy robot, my arms and legs swinging wildly for an instant. That’s when I suddenly remembered that I was surrounded by hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of original art. I literally snapped my heels together and slapped my hands to my hips. Just in time, I realized as I looked around. I had stumbled a foot back from the giant robot. A few inches from my right foot was a stack of paintings leaning against a wall. All of them were oil on canvas and none of them were protected by glass. Top of the stack was J. Allen St. John’s cover painting for Golden Blood, created for the March 1933 issue of Weird Tales and my choice as his finest work. My shoe hadn’t gone through the canvas, but it hadn’t missed by much. I had almost put a six-inch hole through one of the greatest pulp paintings ever published. It was a chilling thought.

The rest of the visit I only examined paintings that were not blocked by any obstructions. In the course of assembling the finest pulp magazine cover painting collection of all time, Bob Lesser had succeeded in putting together an exceptional early SF art collection. There weren’t any black and whites by Finlay, Bok, or Cartier, but he did have numerous paintings by Frank R. Paul. Most of them came from Forry Ackerman, but he had bought others from several well-known fans including one of Sam Moskowitz’s best. Lesser also owned several St. John paintings, including the two Weird Tales covers mentioned. Plus, he had color pieces by Leo Morey, Virgil Finlay, and Lawrence Sterne Stevens.

It was an impressive grouping of paintings. I’m glad I had a chance to see it first-hand. I’m extra thankful that I didn’t badly damage any original. I learned my lesson. Leave giant toy robots alone.

I only wish Bob Lesser had offered everything in his vast collection for sale to art collectors throughout the world instead of recently donating his entire holdings to a museum. Museums and libraries tend to hide art collections away, never to be seen again by the public other than at special shows once every few years.

Fans rescued most paintings from the pulps and science fiction magazines from being destroyed. They tracked down artists, annoyed publishers, spent many dollars of their hard earned money to buy art. Fans deserve to own and enjoy the originals.

~ Next Time ~

My Visit with Edd Cartier

All rights reserved.