Collecting Fantasy Art #11

Collecting Fantasy Art #11

Secrets of New Jersey – Part 1

Two Visits

By Robert Weinberg

Copyright © 2012 by Robert Weinberg

Chapter One

I was born and raised in New Jersey. I attended high school, college and graduate school there. I moved to Chicago in the fall of 1970 to study for my Ph.D. in mathematics. If I hadn’t met the young lady who was to become my wife, most likely I would have returned some day to New Jersey. As it was, I settled down in Chicago and have lived in the city or the suburbs for the past forty years. Still, I have fond memories of the state where I spent my youth. And where I started collecting.

New Jersey, located next to New York City, was a science-fiction fan’s paradise. In the late 1940s and 1950s, during the first boom in science fiction publishing, most major publishers had been located in Manhattan. Equally important, most major authors had lived in the city as well. Ditto editors and illustrators. Many still lived there. Others had moved away, but had left signs of their presence. Collectibles for fans like me.

Early science fiction fandom began in big cities like New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. The first World SF Convention was held in New York City in 1939. There were several active science fiction clubs in the metropolitan area. There was even an excellent SF association located in Newark, New Jersey. Used bookstores were filled with fantasy books and magazines. Important collectors lived in Manhattan or in the suburbs of New Jersey. Surprising artifacts from the 1930s still turned up in the metropolitan area. Incredible stuff.

I didn’t start collecting original art until I was living in Chicago in 1973. However, events in New Jersey foreshadowed my interest in original art. Though I thought myself free of New Jersey in 1970, evidently New Jersey had plans for me that extended out into the future. Some of which are just now unfolding. The world has secrets and some of them are very strange.

Two great collectors lived in New Jersey in the 1950s,1960s and 1970s, and I was lucky enough to meet and know them both. One of them was Gerry de la Ree, and the other one was Sam Moskowitz. I’ve written elsewhere in this memoir about both men and their incredible homes. Gerry lived in a stunning modern home in the north Jersey suburbs. It was built to his specifications and the house was dominated by a huge, two-story library that held Gerry’s many thousands of hardcover books, paperbacks and sf magazines. The walls of his home were covered by original artwork, most of it done by Virgil Finlay. Gerry had acted as agent for Finlay when the artist had developed throat cancer and had helped the artist sell hundreds of originals. Gerry had bought the best pieces Finlay had offered for sale and thus had one of the finest Finlay art collections ever assembled.

Gerry’s collection was displayed in spectacular fashion. He had shelves of collectible hardcover books rising fifteen feet in the air. A twisting metal stairway led to a narrow metal ledge high above the library floor that circled the huge room. There were Finlay originals everywhere, taking up every inch of bare space on the walls. In the center of the room was a huge pool table surrounded by several leather sofas. It was a room meant to impress and it did exactly that.

Not that the rest of the house was any different. There were twenty Finlay’s hanging in the kitchen, and the long hallway outside the library was covered with rows of Finlay and Bok art. There was even art hanging in the hallway leading to the basement! Gerry’s house was the ultimate art collector’s home. Visiting in the mid-1960s, I could easily imagine myself living in a place like his someday. Gerry’s home affected numerous collectors in the same manner.

I got married in May 1973. That summer, I took my wife, Phyllis, to PULPcon and to the World SF Convention held in Washington, DC. So, by fall, she had an idea of what the strange people I dealt with in the SF Community were like. I was already collecting art, as well as SF books, and pulp magazines, so she also was well aware of all my weird obsessions.

That fall, Phyllis and I flew back to New Jersey to visit my parents and some of my relatives. As part of the trip, I made arrangements to visit Gerry de la Ree and Sam Moskowitz. I thought showing Phyllis that some collectors actually had nice homes would be a good idea.

We visited Gerry’s home first. Nestled in Saddle River, a very wealthy north Jersey suburb, it made a good impression. Several years later, Richard Nixon would retire to that same town. Like many fans, I couldn’t help but wonder if Nixon ever visited Gerry de la Ree. Somehow I doubted it.

Phyllis was extremely impressed by Gerry’s home, though she was caught by surprise by the large color paintings by Stephen Fabian of nude mermaids swimming on each side of the doors to the library, with both of the creatures sporting Helen de la Ree’s head. Gerry liked to commission nude artwork by SF artists with his wife’s head atop of a fantasy body. The paintings were definitely conversation pieces.

The two-story library filled with books and pulp magazines made up for the surprise. There was more art than usual. Gerry had just bought a small art collection, one of which pieces was the Weird Tales cover from 1939 of Edgar Allan Poe with a raven. The unframed art, leaning against the black metal stairway, was impressive. It was a spectacular addition to Gerry’s collection.

Sitting on the leather sofas, sipping soft drinks, it was hard not to think that Gerry de la Ree owned the finest SF Collection in the world. However, despite Gerry’s vast holdings, there were some troubles in paradise. Take, for example, the huge Hannes Bok original that hung over the doorway into the library.

Gerry had bought the painting, an unpublished piece some two feet by three feet, from his friend Bok, many years ago, and the piece had hung in Gerry’s home for decades. It was a stunning original with a god-like being, a ball of light, and a stylized human. The colors were dazzling. Or they had been dazzling years ago. During the late 1960s and 1970s, the art had been fading. Bok must have used cheap paint, Gerry advised anyone who asked. The glitter was gone from the illustration.

Bob L, who I have mentioned before in these memoirs, wanted a Bok painting. After visiting Gerry, he decided that he wanted that particular Bok painting. And, whatever Bob L. wanted, he got.

It took him time and a lot of offers, but he finally got Gerry to agree to a price for the painting. I remember it well when the piece was sold, as like many art fans, I never expected Gerry to let a Bok painting leave his home. Still, Bob L. was willing to pay more money than anyone thought the piece was worth. Most collectors thought him a fool. But, no one could argue with the fact that he got what he wanted.

More important was what happened next. Bob L. decided to get the painting reframed. So he brought it to a framer and restorer in New York. The man took one look at the painting and asked Bob L. the magic question. “Did the previous owner of this painting smoke cigars?”

Bob was surprised by the question but answered affirmatively. He also asked the framer how he knew?

“Simple,” replied the man. “There’s a thick layer of cigar smoke covering the painting and the frame.”

Needless to say, Bob L. paid to have the painting restored. A dense mat of cigar residue was removed from the canvas. The paint beneath it was incredibly bright. The piece was restored to its full glory. It was dazzling. Donald Grant reprinted the art as the cover for his Hodgson volume, Out of the Storm. Thus proving beyond the shadow of a doubt that even the top art collectors have their soft spots.

Condition was a problem with Gerry’s collection. His books, his pulps, and his art all smelled of cigar smoke. Plus, the oil paintings on his walls were discolored by the ashes in the air. Amazing how one bad habit could taint an entire collection. Which was not the case with Sam Moskowitz, who Phyllis and I visited the next afternoon. Sam and his wife Dr. Christine Haycock didn’t have any major bad habits. Other than they were both obsessive collectors, which to me was not at all a bad habit.

As I have mentioned elsewhere in this memoir, Sam lived with his wife in a huge doctor’s house in a very old section of Newark, New Jersey. The house was huge, with numerous waiting rooms, examination rooms, and doctors’ offices. The immense building had nine bathrooms. Needless to say, everywhere he had some free space, Sam had put up bookcases filled with hardcovers. The house was two stories high, with a full basement. The entire second floor and the whole basement were filled with books and pulp magazines. Plus, there was art everywhere. Not Virgil Finlay art, as Sam had not bought any art from Gerry. He had a few Finlay originals from years earlier, when he had visited the artist and bought a few pieces that he especially liked. Instead of Finlay’s fine line art, Sam had dozens and dozens of originals by Frank R. Paul decorating the walls.

As we walked through room after room, awed into silence by Paul painting after Paul painting, San explained how he had gotten all the art. In 1953 Hugo Gernsback, who Sam had interviewed a number of times about science fiction and pulp publishing, decided to publish another SF magazine. He asked Sam if he would serve as editor. The salary he offered was not particularly tempting, especially since Sam knew the amount of work involved in running a magazine. But, Gernsback wanted to run an old fashioned magazine, with science articles, art by Frank R. Paul, and fiction by the best writers in the modern SF field. So Sam was tempted. After much thought, he made Gernsback a counter-offer.

Sam agreed to edit the new magazine, SF Plus, but only if Gernsback promised to give him, along with his salary, the mechanicals of each issue of the magazine after it was published. The mechanicals consisted of everything used to produce the publication. The columns of typeset print, the headings for the articles and stories, and the art used to illustrated the stories. Sam didn’t want just the photographic plates for the magazine, but the actual originals used in making the issue. He wanted the guts of the pulp.

Having no choice in the matter, Gernsback agreed. Not that he was giving up much. Usually, the printing plant kept the mechanicals or they were thrown out. No one considered them of much use. At the time, the art used as illustrations for the pulps was considered property of the publisher. Most companies felt that art had no value once used so they didn’t hang onto it. Years later, a court case brought by artists finally gave the art some value and publishers began returning the pieces to the artists, but not until thousands of originals had been destroyed.

Thus, Sam obtained as part of his salary working as editor for SF Plus magazine all of the Frank R. Paul originals and art by other pro artists used in the magazine issues. Not only were there numerous pieces by Paul, there were also color and black and white paintings by Alex Schomburg. And fine originals for a number of other top artists who worked for the science fiction magazines in the 1950s.

Some of this art was offered for auction at the Sotheby’s Auction of the Sam Moskowitz Estate which I discussed in Chapter 9 of this memoir. Several spectacular Frank R. Paul original illustrations from the 1950s were sold at attractive prices. But, by no means were all of the Paul pieces from SF Plus offered for sale. Many of the best originals by Frank R. Paul and other major artists, including Virgil Finlay, were kept out of the auction. But good art surfaces, even though it sometimes takes years for it to reappear.

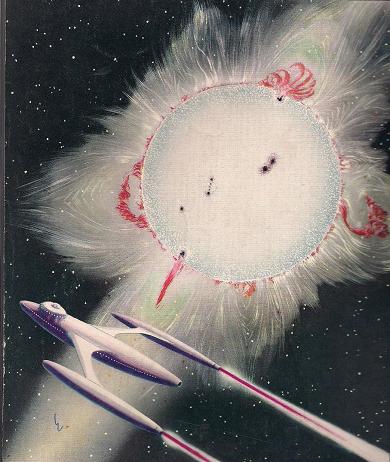

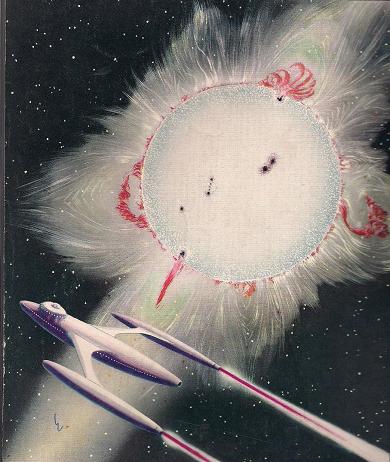

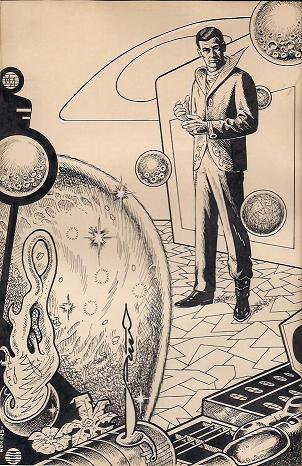

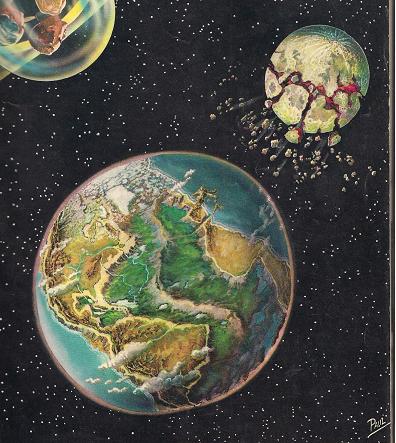

(From Left to Right: SF Plus cover by Frank R. Paul — Amazing illo by Dan Adkins — SF Plus color illo by Frank R. Paul)

Chapter Two

My wife enjoyed seeing the wonders of Sam Moskowitz’s collection and Sam seemed to enjoy showing off the marvels he owned. After a tour of the first floor, which was mostly devoted to doctor’s offices, living quarters, and Christine’s vast elephant collection, we climbed the stairs to the second floor. It was there that most of Sam’s collection was located. A huge bedroom contained no furniture, only six-foot tall steel filing cabinets. Inside each cabinet was stacks and stacks of near mint pulp magazines, piles and piles of the old magazines resting against the heavy duty metal walls. It was a convenient method of storing huge numbers of publications in a relatively small space. The store room contained thousands of pulps stacked up in piles reaching towards the ceiling.

On the far wall of the bedroom were steel letter files. Each file was approximately two feet high, a foot wide and three feet deep. It had two drawers, one above the other, with each drawer protected from collapsing by strong metal rods. Sam had the files arranged in two long rows against the wall, with one row atop the other, so that the files formed a row of twenty metal files, four drawers deep, stretching three feet back to the rear wall. Hanging over these files, Sam had some of the Frank R. Paul paintings he had rescued from the garbage cans in front of Hugo Gernsback’s offices years before.

Sam explained to Phyllis and me that he decided fairly early in life that he was going to chronicle as best he could the history and story of the origins of modern science fiction. To do so, he resolved to write to all the important people in the field and keep up to date with what they were doing. Thus, his letters were extremely important to him, as they contained the facts of the history he was compiling, as told to him by the people who were making things happen. So, in the 1930s, as a teenager, he decided that he would save every letter, no matter who it came from, in his files. That way, if someone he was corresponding with became famous, Sam would have his early letters. It was an ambitious plan, but it was one Sam followed for the rest of his life. His rows and rows of steel file cabinets contained every letter ever written to him, along with a copy of the answer Sam had sent back. Just to prove that his files were complete, Sam looked up my name and pulled out my file. It contained letters that went back into the early 1960s. They were definitely notes that I had sent, years before.

Then, just to show off slightly, Sam pulled out a thick file, several hundred pages thick, of letters he had received from Robert A. Heinlein. The correspondence dated back to 1939, soon after Heinlein broke into the science fiction field. Sam’s file drawers were filled with thousands upon thousands of pages of letters from the not-famous to the not-very-famous to the very-famous. What happened to those files when Sam died, I do not know.

After a few minutes spent staring at the wonderful Frank R. Paul Wonder Stories cover paintings that were behind Sam’s letter files, we followed Sam down the hall into a small, dark, wood room, with a narrow desk, several chairs and the ever-present batch of book cases. For a change, there were glass doors on the wood shelving, though a brief glance at the books by me revealing nothing very special.

It was this room that served as Sam’s office. It was in that room that he had the Finlay original of a girl and a unicorn’s head that the artist had drawn in Okinawa that Sam felt was Finlay’s finest original. It was here, on several shelves near his desk, that he had the numerous awards he had won during his long career as science fiction’s historian. It was here that he kept his greatest book treasures.

We sat down and got comfortable. Having been on our feet, standing, as we looked through the rooms on the first floor and much of the second, we were exhausted. With a broad smile, Sam stood up and walked over to one of the glass-door bookcases. He removed four books from the case and brought them over to the desk and sat down again.

Forever curious, I stared at the jackets of the four books. I was not impressed. They were the jackets of four Fantasy Press hardcovers. After thirty-seven years, I must admit I don’t remember which ones. But I do still remember they were in mediocre condition, with a number of tears and even some small pieces missing. Whatever, the books were not the least bit exciting.

The conversation that took place over the next few minutes sounded something like this.

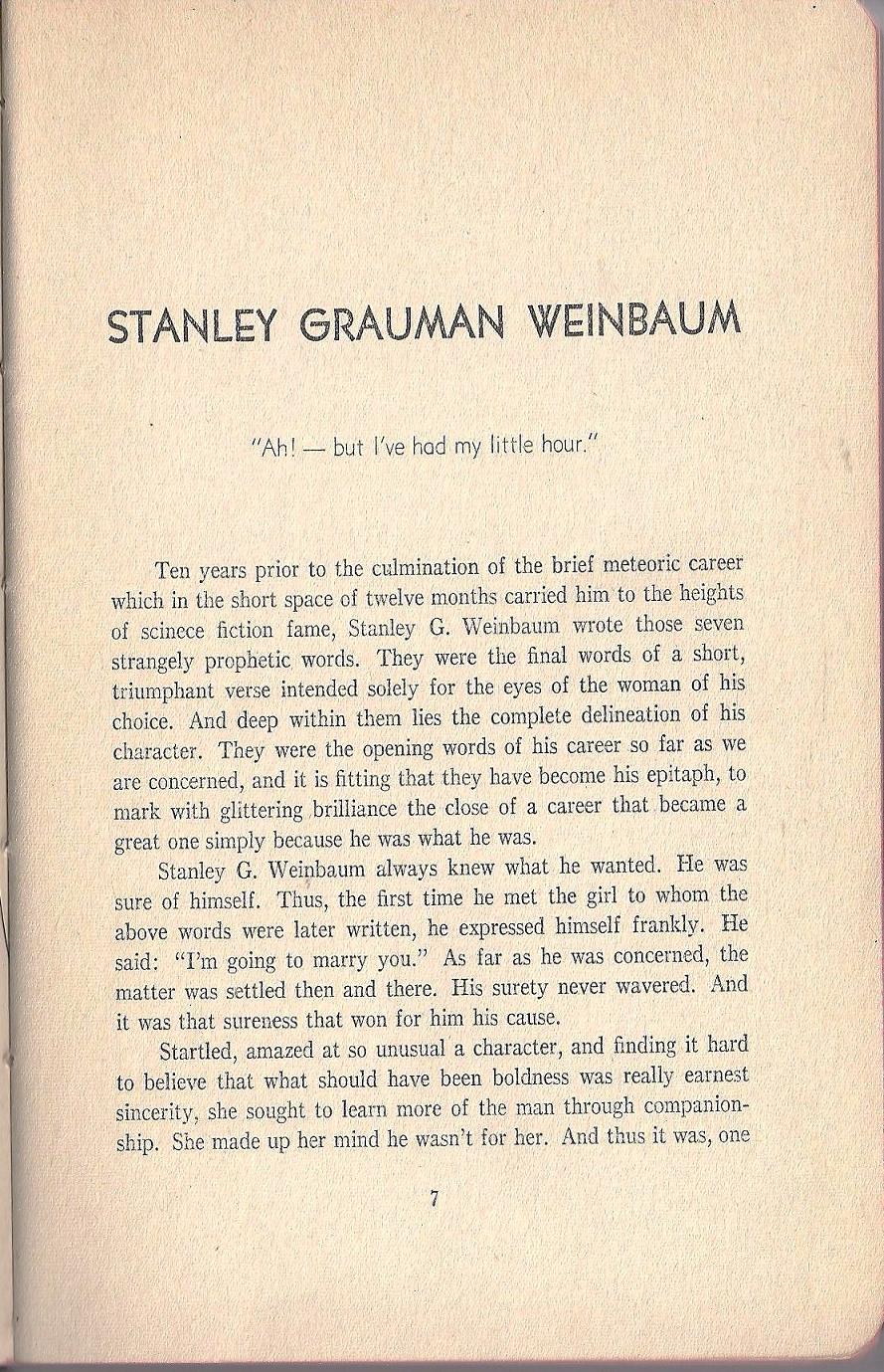

“Do you know anything about Stanley Weinbaum?” Sam asked Phyllis. “Have you read any of his work?”

“No,” said my wife. “Who is he?”

“One of the great writers of early science fiction,” said Sam. “He wrote stories for the pulps for only a few years in the 1930s and then died. It was a tragic end to a wonderful author.”

“Fantasy Press published three books by him,” I added, not sure where the conversation was going. I have them all in my collection.”

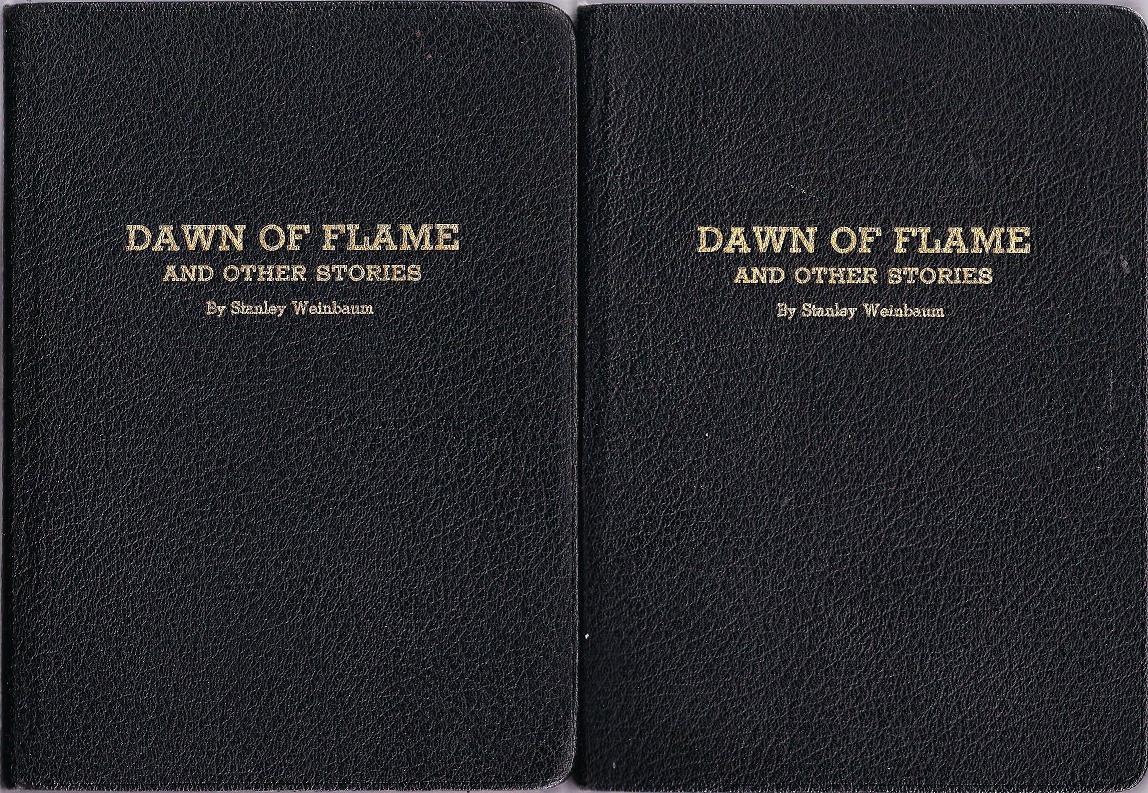

“But those aren’t the books that he’s famous for,” said Sam. “He lived in Milwaukee and was a member of a writer’s group there called the Milwaukee Fictioneers. Robert Bloch belonged. As did Ralph Milne Farley. They decided to publish a memorial book tribute to Weinbaum consisting of his best stories. The book was titled Dawn of Flame, after one of his most famous works.”

“The science fiction Bible,” I remember saying, still not sure why Sam was telling this story. “Fans called it that because the book was published by a Bible printer and resembled a black leather Bible.”

“Exactly,” said Sam. “They printed 500 copies of the book but half the print run was destroyed in a flood. The rest of the copies took several years to sell out. Fans were poor in the Depression and couldn’t afford to buy books. One other thing I want to tell you about the book. Ray Palmer, who belonged to the writer’s group, wrote the introduction. But Weinbaum’s widow thought the piece was too personal and asked that it be dropped from the book. A new introduction by Lawrence Keating, the President of the Milwaukee Fictioneers, was added. Still, five copies with the Ray Palmer introduction were printed. Having read both intros, I found neither of them very personal. Honestly, I suspect that the Palmer introduction was dropped just to create a super-rare edition of the book.”

“What an interesting story,” said Phyllis. “Creating an instant collectible. I assume you have a copy of the regular edition in your collection?”

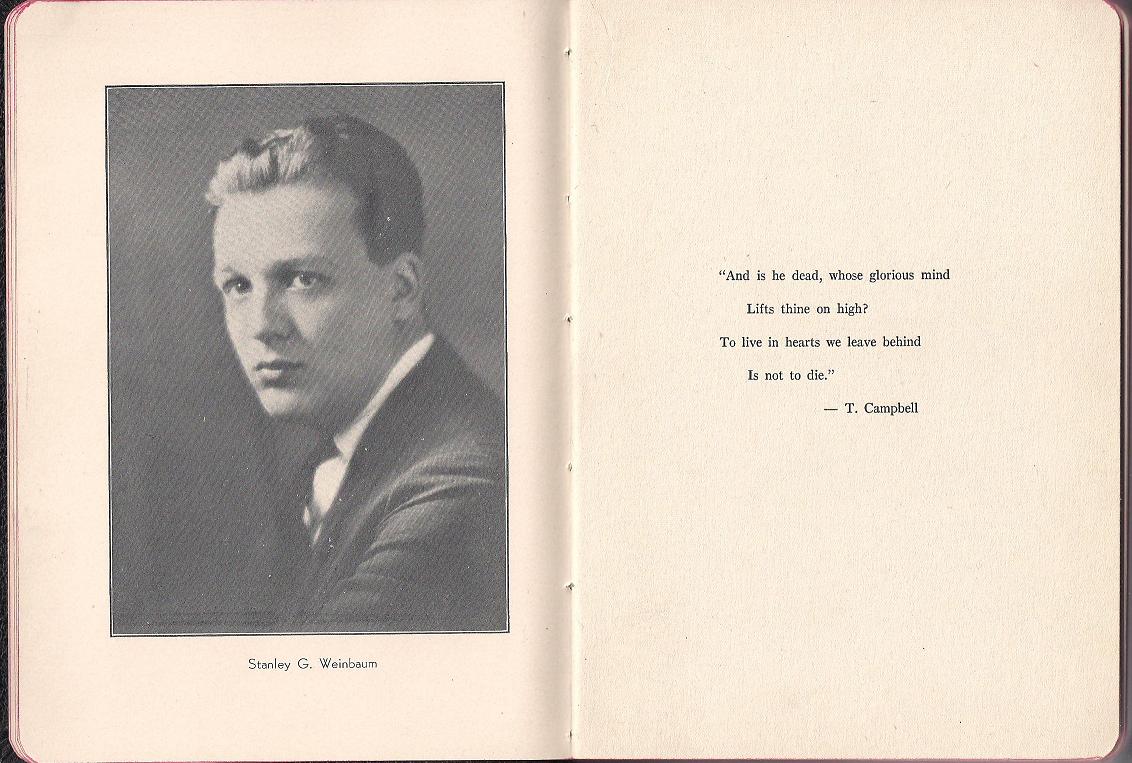

“Here,” said Sam, with a huge grin, removing the dust jacket from the top Fantasy Press hardcover stacked on his desk. The binding beneath the jacket wasn’t Fantasy Press cloth. Instead, the book appeared to be an old-fashioned Bible. It was a copy of Dawn of Flame.

“One of the 250 Keating copies,” said Sam, as my wife carefully examined the volume.

He looked at me. “I keep old jackets on my rarest books, so if anyone breaks into my house, they wouldn’t know which volumes are the valuable ones. Of course, I have to remember which books are the rare ones myself or I can spend all day looking for a title.”

“There were five copies of the volume printed with the original Ray Palmer introduction,” said Sam, turning back to my wife. “Those copies were owned by Ray Palmer, who wrote the original introduction; Julius Schwartz, who worked as Weinbaum’s agent; Conrad Ruppert, who printed the book; Weinbaum’s widow; and Lawrence Keating, who wrote the alternate introduction.”

He reached out and pulled over the three remaining books with Fantasy Press jackets. Dramatically, he removed the worn jackets from the books, revealing the Bible binding beneath each. “Here are three of the five.”

Three copies of the five books printed with the Ray Palmer introduction! It seemed impossible, yet a brief examination of the volumes proved that Sam told the truth. Each book had the Palmer introduction that was longer and much different than the Keating one. Somewhat astonished, I had to ask Sam how he had acquired three copies of the five copy edition.

“I paid close attention to the five people who were given the Ray Palmer copies,” said Sam. “From time to time, I dropped them letters mentioning that if they ever decided to sell their copy of Dawn of Flame, I would be interested in buying it. Years passed. Forrest J Ackerman bought one of the copies. I bought three of them. The last copy is still held by the original owner.”

“Why did you buy three of them?” asked Phyllis.

“With a book so rare that only five copies exist, you buy all the copies you can afford,” said Sam. “I’m happy to own three of the five special editions. I’d buy the other two if I could.”

My wife shook her head in absolute bewilderment. It wasn’t the first time she had been puzzled by the behavior and viewpoints of collectors. Nor would it be the last.

Both versions of Dawn of Flame — Twin Bibles

The first page of the introduction by Ray Palmer — 1 of only 5 copies

Double-page spread of the regular edition of the book — 1 of 250 copies

Chapter Three

Visiting Sam Moskowitz and Christine Haycock in their huge home in Newark, New Jersey in the mid-1970s was an amazing trip for me and my wife, Phyllis. Though I had visited Sam and Chris at their home before I was married, never had I gotten the complete tour that the two of us received that afternoon. Not only did we see Sam’s pulps, his Frank R. Paul paintings from 1929 and 1930, and all of the artwork he accumulated from Science Fiction Plus, but we even got to see his three copies of the Ray Palmer introduction version of Dawn of Flame that he kept hidden in plain sight in his office. It was an incredible display of spectacular rarities and it had me wondering to myself who had a better collection? Was it Gerry de la Ree, with his two-story library and several hundred Virgil Finlay originals, or was it Sam Moskowitz, with his magnificent Frank R. Paul paintings and his unbelievably scarce hardcover books?

Before visiting Sam at his home, I know I would have definitely voted for Gerry’s collection, since I was enchanted by Finlay’s art and felt certain that Gerry’s rare book accumulation couldn’t be matched. However, after seeing Sam’s huge holdings of books, pulps and original artwork, I was less sure of my choice. Plus, the three special editions of Dawn of Flame had made a strong impression upon me. I knew that Gerry had no books that could match those three fan publications. Still, I wasn’t sure if Gerry’s collection or Sam’s was the best. Until Sam showed me his bound sets of Cosmos.

“Cosmos” was a seventeen part round-robin serial published monthly in the early science fiction fanzine, SF Digest, which later changed its name to Fantasy Magazine. SF Digest, published in New York City, was a renaming and reworking of The Time Traveler, the first all science fiction fanzine. The Time Traveler was edited by Julius Schwartz, credited as the Managing Editor; Alan Glasser, the Editor in Chief; Mort Weisinger, the Associate Editor; and Forrest J Ackerman, the Contributing Editor. Glasser was in his twenties, while the other editors were all in their teens. All of the editors lived in New York City, except for Ackerman who lived on the West Coast. The magazine under all of its names was printed by the pillar of early sf fandom publishing, Conrad Ruppert. When Glasser left to concentrate on a writing career, Ruppert took over as Editorial Director.

“Cosmos” began as a serial novel in the July 1933 issue of SF Digest. The first installment of the story was written by Ralph Milne Farley and was titled “Faster than Light.” The novel ran for seventeen (17) installments, and ended in the November 1934 issue of Fantasy Magazine, with the final chapter titled “Armageddon in Space” which was written by Edmond Hamilton.

Somehow, over the years, “Cosmos” has become listed as an eighteen part serial (though the dates are for only seventeen months). The chapters are consecutively numbered and the Hamilton chapter is clearly labeled as Chapter 17. Some of the confusion seems to have been caused by the fact that eighteen writers are listed as contributors. However, E. Hoffmann Price and Otis Adelbert Kline just collaborated on a chapter.

The roster of “Cosmos” contributors was impressive, especially for a fan magazine that didn’t pay anything for contributions. Authors who wrote chapters for the novel included A. Merritt, E.E. Smith, Edmond Hamilton, John W. Campbell, E. Hoffmann Price & Otis Adelbert Kline, David H. Keller, P. Schuyler Miller, Arthur J. Burks, Ralph Milne Farley, Eando Binder, Francis Flagg, Lloyd Arthur Eshbach, Bob Olsen, J. Harvey Haggard, Abner J. Gelula, and Ray Palmer. Palmer appeared twice in the novel, once under his own name and once under his pen name “Rae Winters.”

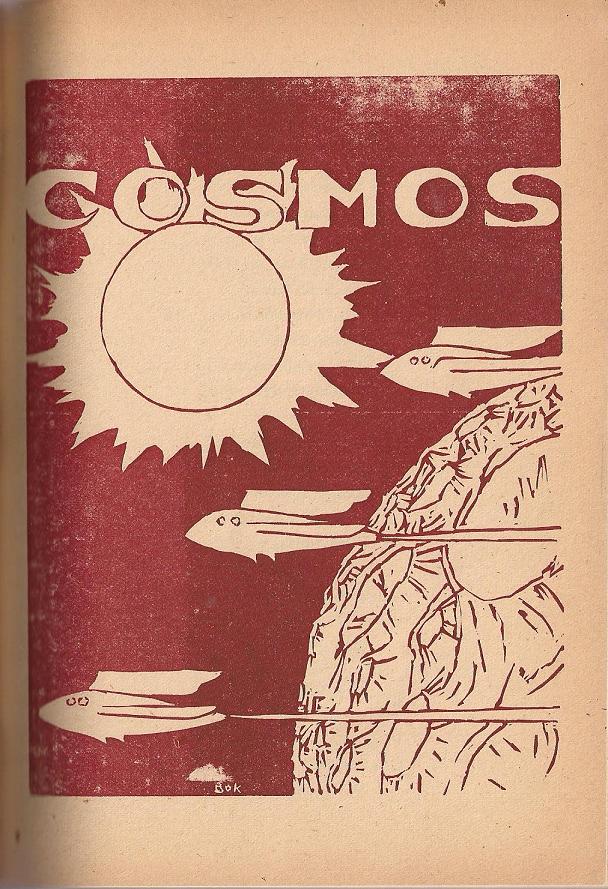

Each installment of “Cosmos” was published as a separate booklet attached to the rear of SF Digest or Fantasy Magazine. Given along with the last installment came a paper cover done by a fan artist who went by the name Bok. It was the first published art by Hannes Bok.

“Cosmos” was something special for early science fiction fandom. It was a novel written in collaboration by the biggest names of science fiction done as a fan project. It was free to anyone who subscribed to the fanzines in which it appeared. It was a unique project and one that has never been matched in the history of science fiction.

Sam Moskowitz told Phyllis and me all about “Cosmos” over coffee and cookies in his kitchen. We had no idea why he went into such depth about the serial, but it was apparent that Sam enjoyed talking to a captive audience and showing off the treasures of his collection. And the two of us were thrilled to see anything he wanted to display.

Back in his office once again, Sam pulled three more books in worn-out jackets off of his bookshelves. “Take a look,” he said, smiling, as he removed the jackets. Each book had a raised leatherette spine with one word on it in gold letters: COSMOS. The volumes were bound sets of the serial – and more!

The open book had fancy red endpapers. Beyond that, on cheap pulp paper, was the Hannes Bok cover illustration. On the other side of the Bok cover was the first page of a two-page table of contents. Each installment of the serial was listed, along with the name of the author who wrote it. Oddly enough, no page numbers were given for the first page of the installments. That was because not all of the segments were the same size. Some were sixteen pages long, while others were twenty pages long.

Normally, with Conrad Ruppert publications, there were no illustrations printed on the pulp paper. Ruppert knew how to publish art on slick white paper (which he used for the covers of Fantasy Magazine) but he was not very skillful in reproducing illustrations on pulp pages. However, as Sam was quick to point out, these bound volumes of “Cosmos” were different.

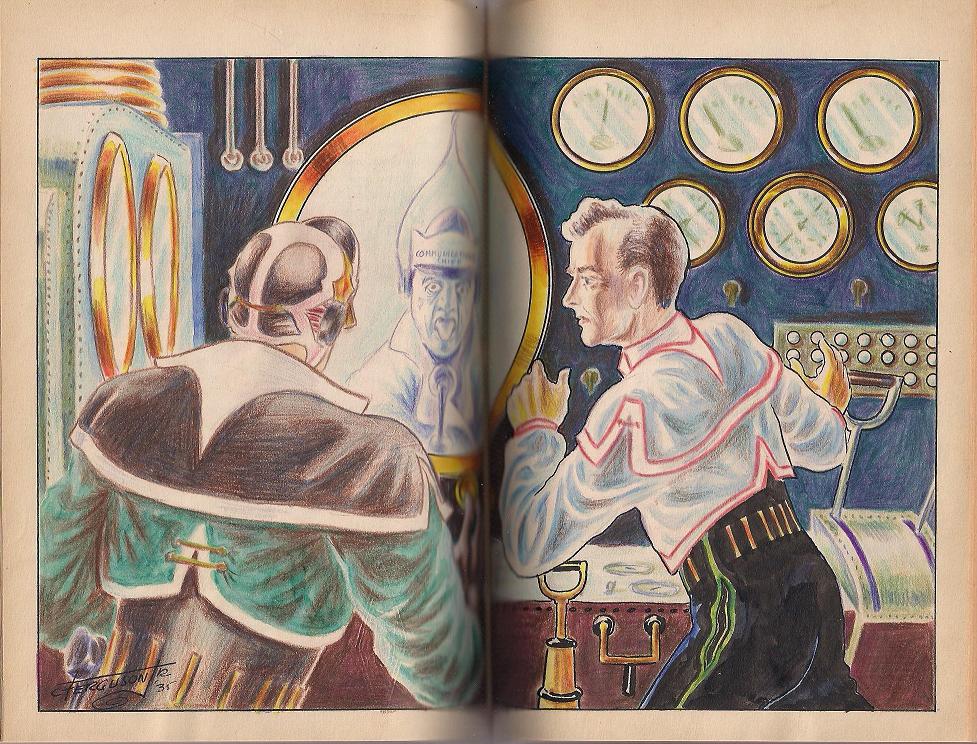

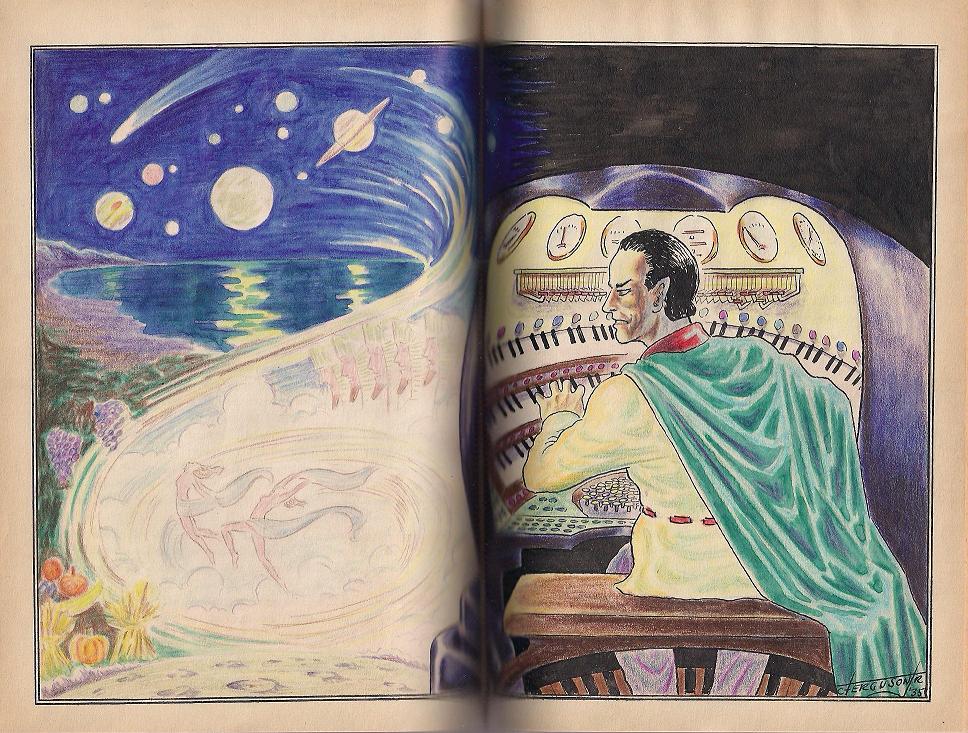

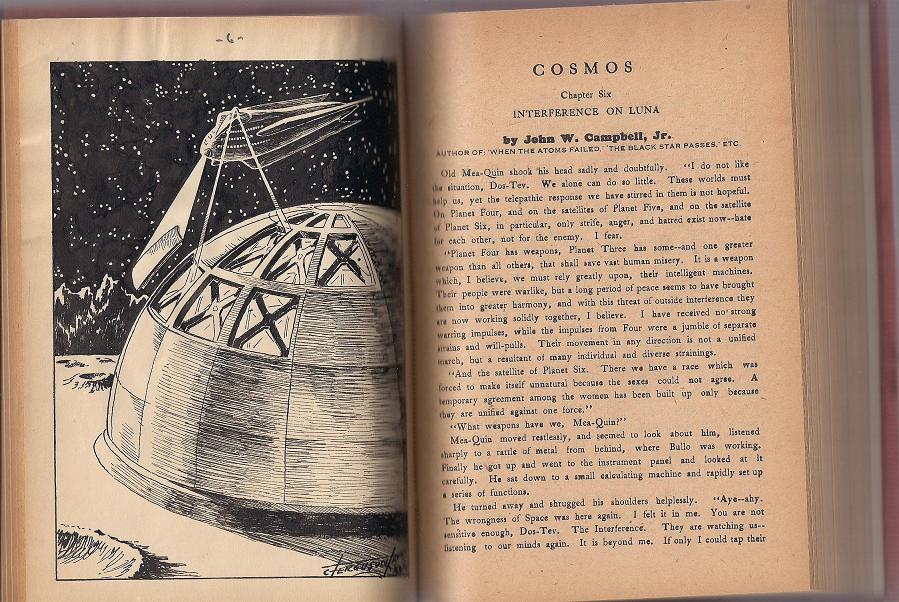

These bound volumes had been assembled for the five editors involved with publishing the serial. To make the books unique, the editors had combined forces and paid Clay Ferguson, the fan artist who composed the cover art for issues of Fantasy Magazine, to do a full page illustration for each installment of the serial. Each illustration was printed on slick white paper in an edition of five copies and was bound in with the complete serial in the proper location. Thus, for every bound copy of the entire novel given to the editors, the hardcover volume contained seventeen black and white illustrations. Making those five bound copies unique. But there was more.

The editors wanted each volume of the five bound sets to be different than the other books. Since the black-and-white illustrations were the same in all five collections, they decided to also include several double page hand-colored illustrations by Clay Ferguson. Two such illustrations would appear in each hardcover and would be available only in that edition. The art would be used only once and would be hand-colored by Ferguson, and not printed. Thus, each book would have two totally unique pictures that would not be available elsewhere. Each bound set of “Cosmos” would thus be different than any other set.

Sam proudly showed us his three bound sets of the serial. What he told us was obviously true, as we saw the hand-colored illustrations in each volume – with the art in each book different than the others. Thus, the bound serials contained seventeen black and white illustrations published in only five books, and two double-page color illustrations published only in one very unique volume. And those double-page illustrations were entirely different for the five bound volumes.

As before, when asked how he had obtained three of the five volumes, Sam told us how he had kept close track of the five editors of the fanzine for years and years, and how he had kept making them offers on the bound volumes until they finally decided to sell. He had three of the five unique books, but he had no idea where the other two might be. He had no desire to sell any of the volumes, since each of them contained different originals than the others. Unlike the special edition of Dawn of Flame, the bound editions of “Cosmos” were truly unique.

Leaving Sam’s home late that afternoon, I felt that I had seen the finest rare book and art collection ever assembled in the science fiction field. Thirty-seven years later, having seen just about every other major collection discussed by fans regarding major accumulations, I still feel the same. Other collections were better in some respects that what Sam had assembled, but in total, his collection was by far the best overall. It was a pleasure seeing it and a shame that it was broken up to be sold. But better that prime pieces of it make their way into the hands of collectors than for all of Sam’s treasures be bought by a library or museum and hidden away from sight for the next fifty years.

Cosmos cover by Hannes Bok

Cosmos double page color illo, one of a kind

Cosmos double page color illo, one of a kind

Cosmos black-and-white illo, with serial installment by John W. Campbell

[Editor’s Note: In email accompanying this installment of his memoirs, Bob states that “this Cosmos stuff has never been seen before (not that the Dawn of Flame material has ever been reproduced elsewhere either!).” Tangent Online is honored to be able to showcase these extraordinary and rare pieces of early science fiction history here for the first time, with gratitude and thanks to Robert Weinberg.]

###

Footnote #1: Those collectors who wonder what happened to the original art from SF Plus, including Frank R. Paul cover paintings, Virgil Finlay interiors, and more, regarding sales, should contact Bob Weinberg via email. He can be reached at R-PWeinberg@msn.com. Be warned, these originals are not priced cheap!

Footnote #2: Collectors who are interested in what happened to the Dawn of Flame hardcover books mentioned in this memoir with an interest in buying one or both books; or the bound volume of “Cosmos” with black and white and color plates by Clay Ferguson also described in this memoir, also with an interest in buying, should contact Bob Weinberg at the email address listed above. Be warned. These items are not cheap!

Addenda: A Few Words About the Hugo Award

Color me stupid. Engaged in a conversation with a close friend in Chicago in late December about the World SF Convention, talk turned to the Hugo Awards. In passing, I mentioned how I had once been nominated for a Hugo Award but never won one. The friend replied that maybe I would have better luck this time. I admitted, rather puzzled, I had no idea what he meant. That’s when he mentioned that I was eligible for the Hugo for Best Fan Writer for my series of articles appearing in Tangent Online. And that being from Chicago, I had a decent chance of getting enough votes to actually make the final ballot, if not win the Hugo.

Now, I know from other discussions with friends who have lost Hugos that campaigning for votes for the award is frowned upon by the convention committees. So, I will keep my big mouth shut and merely suggest that if you plan to join the Chicago World SF Convention for 2012, or if you already belong to the convention, you might consider nominating me on the preliminary Hugo ballot as “Best Fan Writer.” And, for that matter, you might nominate Tangent Online as “Best Fanzine.”

Why not? If you feel my series of articles deserves some recognition or that Dave’s fanzine deserves some credit for publishing such an important historical fan document, please consider us when nominating. I won’t cloud the issue with facts. I just think it’s time for a change. So, when you get your preliminary ballot, VOTE!!!!

~Next Time~

Memoir #12 covers Bob meeting a famous artist, almost putting his foot through a famous painting, and buying a fabulous collection.

Text and art copyright © 2012, Robert Weinberg and Tangent Online.

All Rights Reserved.