Once the decision had been made to add The Pulp Magazines category, the first person to come to mind for a possible article on the pulp magazine experience was Robert Weinberg (photo at left). We’d known of Bob’s long experience with and love of the pulps but knew getting him to write an article for us–for free–was a long shot, for Bob is busier than ever these days. He not only is editor at the legendary publisher Arkham House, but edits collections on all manner of subjects and writes the occasional novel and short story as well. And rumor has it that he is working with Hollywood on some mysterious project. We were thus extremely pleased when Bob wrote to say that not only would he be happy to write the initially requested one article, but a series of them for us.

Once the decision had been made to add The Pulp Magazines category, the first person to come to mind for a possible article on the pulp magazine experience was Robert Weinberg (photo at left). We’d known of Bob’s long experience with and love of the pulps but knew getting him to write an article for us–for free–was a long shot, for Bob is busier than ever these days. He not only is editor at the legendary publisher Arkham House, but edits collections on all manner of subjects and writes the occasional novel and short story as well. And rumor has it that he is working with Hollywood on some mysterious project. We were thus extremely pleased when Bob wrote to say that not only would he be happy to write the initially requested one article, but a series of them for us.

During our correspondence Bob revealed why he turned to the pulp magazines as the source of his greatest reading pleasure, a revelation we certainly understand and to a great degree share:

“I must admit that after following the field for so many years, good and bad, I finally realized about six or seven years ago that I didn’t really find most modern sf — the best of it — very interesting. A few authors still entertain me — Peter Hamilton and Alastair Reynolds for certain, as I love long complicated space opera which they do extremely well — but they are exceptions in an otherwise dreary genre. Thus, I abandoned reading most sf and fantasy except for the rare winner and instead devoted myself in general to my lifelong love of pulp literature. And, to be perfectly honest, I haven’t regretted a minute of it!”

We hope you enjoy this first of Bob’s articles, and along with us look forward to future installments recounting his many decades collecting pulp magazines and their eye-catching art.

Collecting Fantasy Art #1

Starting at Zero

By Robert Weinberg

Copyright © 2010 by Robert Weinberg

I own one of the finest collections of original science fiction and fantasy art in the world. My collection is particularly nice in regards to the first Golden Age of SF, the late 1930’s and early 1940’s. I own approximately 100 pieces by Virgil Finlay, including over 20 color originals. I also have twenty Edd Cartier’s, about an equal number of Hannes Bok pieces, and twenty or so pieces by Lawrence Sterne Stevens.

It’s taken me nearly forty years to assemble my collection. During that time I was involved with many of the major deals involving art in the science fiction field. I’ve bought and sold hundreds of paintings and black and white originals. I never cheated anyone and by and large, I feel I treated just about every collector I dealt with, with respect. No one was ever cheated by me in dealing for art, and my word was and is my bond.

How I amassed approximately four hundred originals by many of the top artists in the SF and fantasy fields is the subject of these articles. I started with nothing, not one piece of art, nearly four decades ago. It took me years to accumulate my collection. It’s a long, complicated story and involves many well-known figures in the science fiction collecting field. I hope it proves to be of some use for collectors to come. I know I could have used some help during my years and years of building my collection.

I started collecting science fiction and fantasy art the last weekend of June in 1972. I remember the time so well because it was a week after the first PULPcon, the annual convention aimed at pulp magazine collectors, and shortly before I met the young lady who was to become my wife. If ever there was an alignment of the spheres in my life, it was that weekend. First, though, some background.

I was twenty-five years old. My 26th birthday was a mere two months away, at the end of August. I had been collecting pulp magazines since I was thirteen years old, a natural progression that had come from my earlier hobby of collecting science fiction magazines. Pulps, 6×9 inch magazines mostly with rough edges and printed on cheap pulp paper, was the name given to most of the popular fiction magazines published in the period from 1900 to 1954, when they were gradually replaced by paperback books and slick paper magazines. Early science fiction was published in the pulp magazines and anyone who wanted to get a flavor of the time and place needed to read those magazines. Having collected science fiction magazines since I was a mere child of eleven, I was well on the way to having a complete run of all the science fiction pulps. At the time of the first PULPcon, held in St. Louis in 1972, I only needed a few fairly expensive examples of early pulps to complete my collection. However, bitten by the collecting bug, I was already heavily into collecting another style of publication, the notorious continued character pulps, or as they were nicknamed by fans, the Hero pulps.

The pulp magazines covered every field of popular fiction. There were detective pulps, love pulps, adventure pulps, mystery pulps, sports pulps, western pulps, science fiction pulps and superhero pulps. I collected science fiction pulps, but I owned a fairly large smattering of other pulps, especially in the detective and mystery fields, and in the single character field.

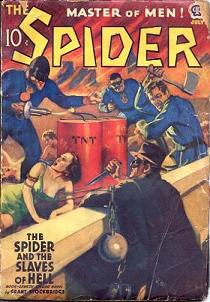

Years earlier, I had stumbled across the single character pulp magazines at a science fiction convention in New York City. I was there looking for rare SF. A dealer there was selling single character pulps. I couldn’t help but notice one from 1939, an issue of The Spider. The lead story was “The Spider and the Slaves of Hell.” The cover illo showed a masked hero, the Spider, climbing over the top wall of a high building. A bunch of women were trapped there, tied to a huge stack of dynamite. The insane-looking crooks were lighting fires and doing other nefarious deeds, mostly just looking crazy. Obviously, the Spider had come over the wall to help the women and defeat the crooks. But, just to keep the match fair, somehow the Spider had been burdened with a ball and chain around one foot to weigh him down. The cover sold me and I bought the issue. And have been collecting The Spider and similar pulps ever since.

Years earlier, I had stumbled across the single character pulp magazines at a science fiction convention in New York City. I was there looking for rare SF. A dealer there was selling single character pulps. I couldn’t help but notice one from 1939, an issue of The Spider. The lead story was “The Spider and the Slaves of Hell.” The cover illo showed a masked hero, the Spider, climbing over the top wall of a high building. A bunch of women were trapped there, tied to a huge stack of dynamite. The insane-looking crooks were lighting fires and doing other nefarious deeds, mostly just looking crazy. Obviously, the Spider had come over the wall to help the women and defeat the crooks. But, just to keep the match fair, somehow the Spider had been burdened with a ball and chain around one foot to weigh him down. The cover sold me and I bought the issue. And have been collecting The Spider and similar pulps ever since.

So, recapping, I was attending PULPcon #1 in St. Louis, near the end of June in 1972. I was buying rare science fiction magazines and was keeping my eyes open looking for single character (or hero) pulps. And somehow this was going to lead into me collecting fantasy art.

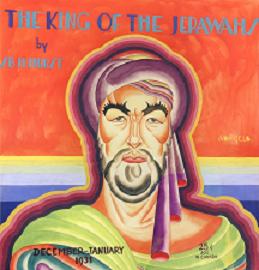

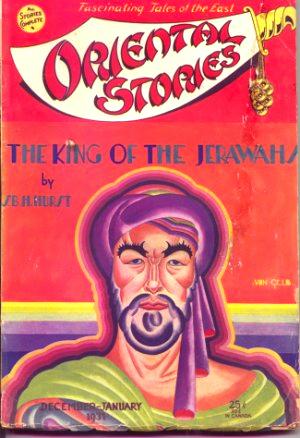

Came the last day of the event. Ed Kessel, the fan who had been the main organizer of the convention, had invited the guests, negotiated with the hotel (a very fancy one) and done a lot more than anyone expected of him, confessed to having lost a bundle running the show. Several thousand dollars, and that was in 1972 dollars, when cash money still had some buying power. In an effort to help retire that debt, a bunch of us attending the convention donated pulps to be sold in a free-form auction that afternoon. I mention this for only one reason. The most expensive item sold at that auction was a copy of Oriental Stories #1, from 1930, in very good condition, which I donated. It went for $29. The most expensive pulp in the auction for $29! These days, a fine copy of the same pulp would probably sell for $500 but that’s inflation and greed stepping in to bid. I offer this information as a sign-post as to what prices were like back in those days. It’s worth remembering.

The regular auction was held that same afternoon. Ed had contacted Walter Baumhofer, a famous pulp artist who was still alive, but these days working for Field & Stream. Surprisingly, Baumhofer had about ten paintings he had painted for the pulps still in his attic. He sent them to Ed along with a note setting the minimum bid at $75. Among the pieces were several Pete Rice western pulp covers, two Doc Savage pulp covers, including the cover for the first issue of the magazine, a gruesome Dime Detective cover; several Dime Mystery covers, and more. Every painting sold for at least the minimum though a number sold for just that price. The first issue of Doc Savage sold for $225, which was the high price for a painting in the auction. In passing, Ed mentioned that Baumhofer had several more cover paintings for sale in slightly damaged condition if anyone was interested.

I attended the auction as an interested observer. A friend of mine had told me to bid on any painting that looked like it wasn’t going to meet the minimum, but that didn’t happen. Every piece in the auction sold, and sold for at least the minimum. So, I never bid on any of them.

However, sitting through the entire auction, I left the proceedings with a collector’s epiphany. Pulps, I reasoned, were rare, and some pulps, like the Oriental Stories #1 that I had sold at the auction, would always bring in a good price due to their rarity. But, despite all the hype and glory, the facts didn’t change. There was no pulp so rare that another copy of the same magazine couldn’t be found. There were no unique pulps, though there were plenty of rare ones. But original art was one-of-a-kind. If you owned the painting for a cover of a magazine you owned something unique. Same thing was true for the interior illustrations for that magazine. The interior art, good or bad, was still always unique to that story. Collecting rare pulps was a terrific hobby with satisfying results. Collecting original art was also a unique hobby, with even more spectacular rewards. So, just for the hell of it, I decided that I would try to collect original art. If I found that original art collecting was too difficult, too frustrating, I would quit. In the meantime, I would continue to collect pulp magazines.

So I returned home from St. Louis, from the first PULPcon, determined to become a science fiction and/or pulp magazine art collector. I assumed it wasn’t going to be easy but also assumed that my years of collecting rare pulp magazines would help me fight the good fight. I was about a month shy of my twenty-sixth birthday and was an associate professor at Illinois Institute of Technology, located in the middle of the city of Chicago. To help pay the bills, I worked as assistant Dormitory Advisor and thus lived on the third floor of the freshman dorm on campus. I was in charge of keeping the peace in the dorm, while attending night classes working on my Ph.D. in mathematics. Living in a dorm room, I had little storage space, so everything I bought for my collection was shipped home to New Jersey shortly after I bought it. I was earning around three thousand dollars a year along with receiving free tuition. It wasn’t a particularly exciting life, but it was good enough.

There are a number of tricks that hardcore collectors use to bolster their collections and continually add new items to the mix. One of the simplest and the first trick I used to jump start my art collection was telling my friends. I returned to the IIT dorms on Sunday from PULPcon. The next week, starting Sunday night and continuing day after day and night after night, I told everyone I knew in the SF/Fantasy field that I had decided to collect art. I called people and engaged in mindless chatter for ten or twenty minutes and then informed them of my new interest. I talked to people in Chicago and I talked to people in New Jersey, New York, and California. I talked to just about everyone I could think of about fantasy art and my reasons for collecting it. By the end of the first week, all of my friends knew that I was looking for original art. And some of them knew where to find it.

My good friend, Frank, from Chicago, mentioned that he had seen what he thought was an Oriental Stories cover displayed in the window of the Gallery Book Store on Clark Street in Chicago. While this seemed like an incredible longshot, I knew Frank pretty well and he was not a person who made up things. Moreover, the Gallery Book Store was a used bookshop that some years back had displayed eight Margaret Brundage Weird Tales covers in the store window. The paintings had come from a Weird Tales fan who had bought them directly from Mrs. Brundage many years earlier and then had sold them to the Gallery during a run of bad luck. I had heard all about the Brundage paintings, but by then they had been sold “for big money” I’d been told, to Chuck Wooley who lived in downstate Illinois. So, the possibility of Tony, the owner of the Gallery Book Store, possessing an Oriental Stories cover wasn’t too outlandish.

Determined to find out the truth and perhaps start my collection with a rare 1930’s pulp magazine cover, I set off that Saturday for the Gallery Book Store. At that time, before urban renewal in downtown Chicago, the store was located a block north of the Chicago River on Clark Street. It mostly had a huge stock of magazines that were on large flat ottoman’s with several drawers of magazines in storage. I remember entering the store with $100 in my wallet and worrying that I might not have brought enough money. After a few polite words of greeting, I asked Tony if he had an Oriental Stories cover for sale. He looked at me funny for a second, then answered, “yes.”

Without another word he walked over to one of the ottoman’s, opened a drawer, and began pulling magazines out. There were dozens of Life and Look magazines, all in good condition, from the 1950’s. But he wasn’t interested in the slick publications and neither was I. After about two minutes of digging, Tony uncovered a fairly large watercolor painting wrapped in a plastic laundry bag. It was the cover for the second issue of Oriental Stories (December 1930), done by Donald von Gelb. On the back of the cardboard was a pencil sketch of the final painting. Evidently the artist had been dissatisfied with his initial attempt and had reversed the board and redrawn the cover. The finished piece was quite impressive, except for a number of tiny holes that dotted the cardboard. I pointed them out to Tony and the book dealer looked somewhat uncomfortable.

Without another word he walked over to one of the ottoman’s, opened a drawer, and began pulling magazines out. There were dozens of Life and Look magazines, all in good condition, from the 1950’s. But he wasn’t interested in the slick publications and neither was I. After about two minutes of digging, Tony uncovered a fairly large watercolor painting wrapped in a plastic laundry bag. It was the cover for the second issue of Oriental Stories (December 1930), done by Donald von Gelb. On the back of the cardboard was a pencil sketch of the final painting. Evidently the artist had been dissatisfied with his initial attempt and had reversed the board and redrawn the cover. The finished piece was quite impressive, except for a number of tiny holes that dotted the cardboard. I pointed them out to Tony and the book dealer looked somewhat uncomfortable.

“We used it for a dart board,” he finally admitted. “Hung it up against a wall and then threw darts at the face.”

I was aghast, but forgiving. For all I knew, that might have been the only reason Tony and his cronies had kept the cover. “How much do you want for it?” I asked, my heart in my throat. I could always leave a deposit on the artwork and come back with more money to pick up the painting, I reasoned. There was no way I was going to let a cover for an extremely collectible magazine from 1930 escape me.

Tony spent four or five minutes staring at the painting he held in his hands. I could almost hear the grind of gears in his head as he thought. Finally, he looked me square in the eyes and declared, “How about eleven dollars?”

I didn’t question how he had come up with this sum or why. I just mentally thanked my lucky stars and paid him the money. Five minutes later, the painting no longer wrapped in the plastic bag but instead under my arm, I was out the door and back on the street in Chicago. I had no real place to store the painting in my dorm room, but I didn’t care. I owned a painting, my first, and definitely not my last.

A few days later, another friend, Art Dobin, called me. He had heard through the grapevine that I was looking for old science fiction and fantasy art. Years before at a World SF Convention held in Chicago, he had bought a Kelly Freas cover painting for The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. It had cost him $50 in the auction and another $40 to get the painting nicely framed. If I was interested, he would sell it to me for the $90 he had into the piece.

I went to see Art that afternoon. The cover he had bought illustrated the first part of Robert A. Heinlein’s classic SF novel, The Door Into Summer. He had paid $50 for it back in 1961. I was quite happy to pay him the $90 for the art and the frame. Freas paintings from the 1950’s were rare by 1972 and when found were going for a lot more than $90. It was my second painting.

The next weekend was the first-ever three day Comic Book Convention in Chicago. It was organized by a school teacher, Nancy Warner, and was little more than a comic book flea market for three days, with one professional guest, Buster Crabbe, who gave a talk or two. I sold comics there. Of course, I put up a small sign saying I was looking to buy science fiction art.

It pays to advertise.

The second day I was at the show, Bob M. introduced himself. He was a collector from Madison, Wisconsin, and he couldn’t help but noticing my sign advertising for SF art. He didn’t have any to sell, but he had several paintings in the trunk of his car he had brought down to display at the show if they had a free display area. They didn’t, so he hadn’t, but he would be glad to show them to me.

I agreed and he did. Bob explained to me that he had found these treasures, a bunch of cover paintings from Amazing Stories and Fantastic Adventures from the 1940’s, in a small out-of-print book store in New Orleans. Most, though not all of the art, was by Robert Gibson Jones, a vastly underrated artist who worked almost exclusively for Ziff Davis. Bob had been stationed in New Orleans when he was in the Navy a few years earlier. “Was the store still there?” I asked, hoping for a miracle.

I agreed and he did. Bob explained to me that he had found these treasures, a bunch of cover paintings from Amazing Stories and Fantastic Adventures from the 1940’s, in a small out-of-print book store in New Orleans. Most, though not all of the art, was by Robert Gibson Jones, a vastly underrated artist who worked almost exclusively for Ziff Davis. Bob had been stationed in New Orleans when he was in the Navy a few years earlier. “Was the store still there?” I asked, hoping for a miracle.

It definitely was, Bob M. told me, and seeing where my thinking was going, finished my thought. And the proprietor had two paintings from the same magazines and the same period that Bob had not bought. Plus, Bob even had his address and his phone number.

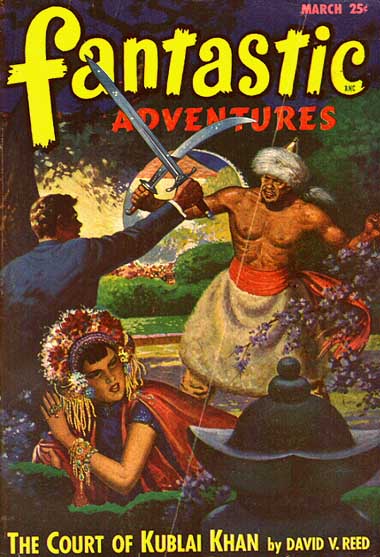

I called that rare book dealer the day after the convention ended and I bought both paintings which he still had in the store room of his shop. He shipped them to me Fed Ex and I had them in less than a week’s time. The Fantastic Adventures painting was used to illustrate the cover story of the March 1948 issue, “The Court of Kublai Khan.”

Now, though I was getting art wealthy, I was also having problems. I couldn’t hang up the art in the cinder-block cement walls of the dormitory. While I was compensated fairly, it wasn’t like my job made me rich. I had only so much money and some of that had to pay for necessities like shoes and clothes and life in general outside the dorm. I managed but I would have preferred a somewhat better standard of living.

So I decided to sell a painting. It was one of those crossroads of life that collector’s reach if they stay in the hobby long enough. Do you start selling off your collection and spend the proceeds on yourself, or do you continue to collect, even if it means your life is not as well-rewarded as you like. To be honest, at the time, I was torn between the idea of collecting rare pulp art and living large. Life in a dormitory, even as an advisor, was nothing special. And, being 25, with years of study left before I would ever achieve my Ph.D. in mathematics, I was starting to miss the good things that life had to offer.

So I decided to sell a painting. It was one of those crossroads of life that collector’s reach if they stay in the hobby long enough. Do you start selling off your collection and spend the proceeds on yourself, or do you continue to collect, even if it means your life is not as well-rewarded as you like. To be honest, at the time, I was torn between the idea of collecting rare pulp art and living large. Life in a dormitory, even as an advisor, was nothing special. And, being 25, with years of study left before I would ever achieve my Ph.D. in mathematics, I was starting to miss the good things that life had to offer.

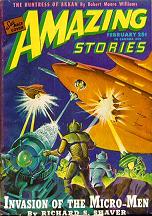

The painting I decided to sell was the Feb 1946 cover to Amazing Stories, one of the two pieces I had bought from that dealer in New Orleans that Bob M. had put me in touch with. I paid $100 for it, so I priced it at $225, reasoning I could bargain downward to $200 and still double my money. Plus, I thought that the painting, while nice enough, was the least exciting of any I owned. If I sold this one, I would be certain that the others could sell.

I sold the Micro-Men cover in three days. Several people were interested, but one fanatical collector from New York City decided he wanted the piece and that was that. He sent me the money, all in cash, and the deal was done. It was a lightning fast transaction and left me wondering what sort of prices I might get for the other pieces I had held onto.

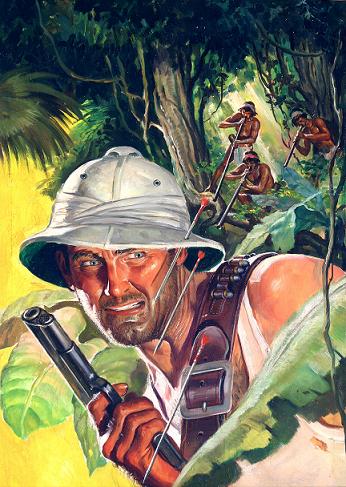

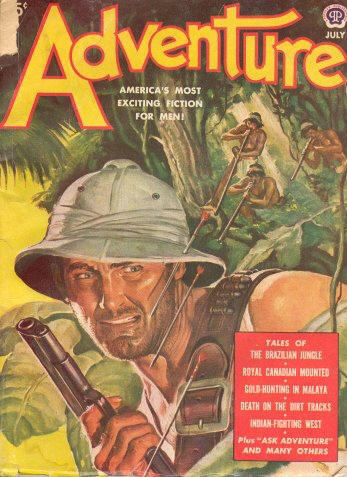

I didn’t have much time to find out. That same week, Arthur J. Burks died. Burks had been a writer during the early days of Weird Tales, and had continued to contribute to the pulps up through the 1950’s. We had been exchanging letters for the past year or so. Soon after the man’s passing, his wife contacted me. Years ago, Burks had been given a cover painting to a 1949 issue of Adventure magazine that illustrated one of his stories. Would I be interested in buying it?

I didn’t have much time to find out. That same week, Arthur J. Burks died. Burks had been a writer during the early days of Weird Tales, and had continued to contribute to the pulps up through the 1950’s. We had been exchanging letters for the past year or so. Soon after the man’s passing, his wife contacted me. Years ago, Burks had been given a cover painting to a 1949 issue of Adventure magazine that illustrated one of his stories. Would I be interested in buying it?

Of course I was. We negotiated a price and I got the painting. It was another large piece with no place to store it other than one side of my room. Collecting art was beginning to generate its share of problems. Besides, having sold the one painting in near-record time (for my humble efforts as a book seller) I had to decide whether to keep the art that was crowding me out of my room, or sell it and make a nice profit I could use to live better. The choice had grown more complicated since I had met a delightful young lady who I was dating and would later marry.

After much inner turmoil, I decided I would keep on collecting but also keep a close eye on my finances. The one nice thing about collecting rare items is that there is never a slow period for unique items. I had no doubts that if I needed money in a hurry, I would be able to exchange my paintings for cash almost immediately. Over the years, that fact has never wavered. Whenever I’ve needed a quick infusion of cash, I’ve sold a painting. They never last more than a day or two. Art sells no matter what shape the economy is in.

Fast forward to the early days of summer 1973. Phyllis and I are just married. We are living in an apartment on the grounds of IIT, where my wife is studying across the street to be a music teacher. I am still working on my Ph.d, and teaching MBA students basic mathematics skills.

Living in an apartment meant that we had walls we could decorate. On several of them went reproductions of some of our favorite movie posters. On others, we hung up some of the paintings I had acquired over the past year. My collecting binge had come to an end shortly after I had met Phyllis, my wife-to-be. I had run out of money, though not the desire to collect original art. My collecting had just been put on hold.

The rent on the apartment was dirt cheap and our living costs were pretty minimal. Phyllis taught accordion lessons to young children at their homes, which pulled in some extra money. And, I sold rare books when possible also to earn some extra cash.

In June, Alex E. came over to visit, bringing his wife who was also named Phyllis, along for the trip. Alex had been collecting SF art for years and he had accumulated a magnificent collection. Most of his collection consisted of original cover paintings from 1950’s and 1960’s science fiction magazines. He also specialized in art by Kelly Freas and Ed Emsh, two giants of the science fiction field of the 1950’s.

Alex wanted to trade but I didn’t have anything I was willing to give up. He had the cover painting done for the 2nd part of The Door into Summer by Heinlein and I had the first. Neither of us was willing to trade their painting to the other. Alex told me that the third painting, a lesser piece, was also floating around on the collector’s market. I remembered the piece and wasn’t really interested.

At the end of the day, with no trades done, Alex did sell me one painting. Years before, Alex was at an auction where two paintings by Lawrence Sterne Stevens had come up for auction. No one bid on them, so Alex threw in a low bid, just above the minimum. He ended up with both paintings, though he was not interested in either. He was willing to sell one if I was interested. I was, and I bought the painting for “Crashing Planets” from Alex for a rock-bottom price.

At the end of the day, with no trades done, Alex did sell me one painting. Years before, Alex was at an auction where two paintings by Lawrence Sterne Stevens had come up for auction. No one bid on them, so Alex threw in a low bid, just above the minimum. He ended up with both paintings, though he was not interested in either. He was willing to sell one if I was interested. I was, and I bought the painting for “Crashing Planets” from Alex for a rock-bottom price.

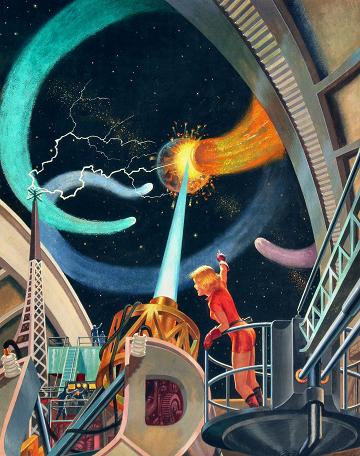

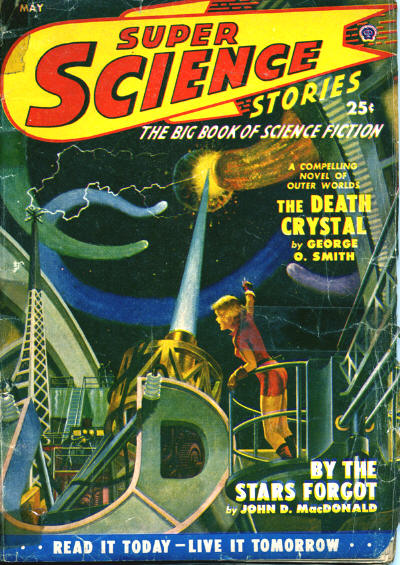

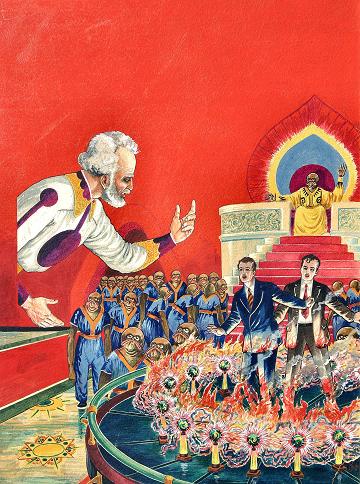

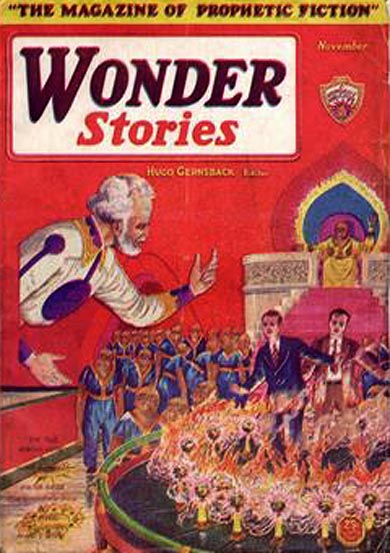

The second PULPcon was held in a hotel in downtown Dayton, Ohio. The convention was in the basement of the hotel. I volunteered to put on an art exhibit. All part of my attempts to become known as the leading buyer and collector of original art in the SF/Fantasy field. I was able to get Bob M. to display his paintings and Rusty H. who had bought the cover of the first Doc Savage pulp was happy to exhibit it. The big surprise of the art show was Ben Jason, a science fiction book dealer from Cleveland, who brought three Frank R. Paul paintings, along with a striking piece by Malcolm Smith, and another stunning painting, by Harold McCauley, all to be auctioned off at the show.

Unfortunately, by the time the auction rolled around, most everyone had spent all their money on rare pulps and collectible magazines. The art auction was a failure. A Frank R. Paul painting done as the front cover for the 1955 World SF Con program book sold for $100 to Stuart S. An H.W. McCauley cover painting for Imagination showing a gigantic human hand reaching for a small group of explorers leaving a space ship on a far planet went for $59, and then Jason had enough. With a cry of anger and annoyance, Jason stood up and declared that the art was no longer for sale. He had not expected high prices, but the extraordinary low prices were too hard to take.

I hurried out of the room, anxious to talk to Jason. There was still time to make a deal. Unfortunately, I was not the only one who had that idea. I was able to buy one of Ben’s remaining Paul paintings, but the other one went to Bob H. who also bought the book dealer’s Malcolm Smith piece. In the end, Jason ended up selling three Paul paintings along with one each by Malcolm Smith and another by H.W. McCauley. I got one of the Paul’s (the November 1930 Wonder Stories), but I paid close attention to who got the other paintings.

I hurried out of the room, anxious to talk to Jason. There was still time to make a deal. Unfortunately, I was not the only one who had that idea. I was able to buy one of Ben’s remaining Paul paintings, but the other one went to Bob H. who also bought the book dealer’s Malcolm Smith piece. In the end, Jason ended up selling three Paul paintings along with one each by Malcolm Smith and another by H.W. McCauley. I got one of the Paul’s (the November 1930 Wonder Stories), but I paid close attention to who got the other paintings.

Thirty-six years later, I own all five of the paintings sold at that show. Patience and a good memory pay off in the long run.

Next Installment: “Aces and Earls,” a winning hand!

***

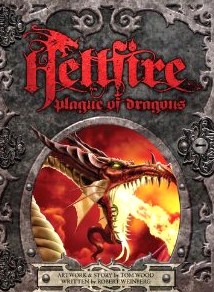

Bob Weinberg is the author of 17 novels, 16 non-fiction books and around a hundred short stories. He’s also edited over 150 anthologies. He owns one of the finest SF/Fantasy original art collections in the world. These days, Bob is busy promoting his new book, Hellfire: Plague of Dragons, done with artist Tom Wood, and serving as editor for Arkham House publishers.

Bob Weinberg is the author of 17 novels, 16 non-fiction books and around a hundred short stories. He’s also edited over 150 anthologies. He owns one of the finest SF/Fantasy original art collections in the world. These days, Bob is busy promoting his new book, Hellfire: Plague of Dragons, done with artist Tom Wood, and serving as editor for Arkham House publishers.