Cosmos – A Triumphal Failure of Early Science Fiction

by

David Ritter

(January 2015)

![]()

Introduction

[Left: From Science Fiction Digest, April, 1933, “The Editor Broadcasts” by Conrad Ruppert — Right: From IF!, January 1949, “Cosmos – a trivial review” by Don Wilson]

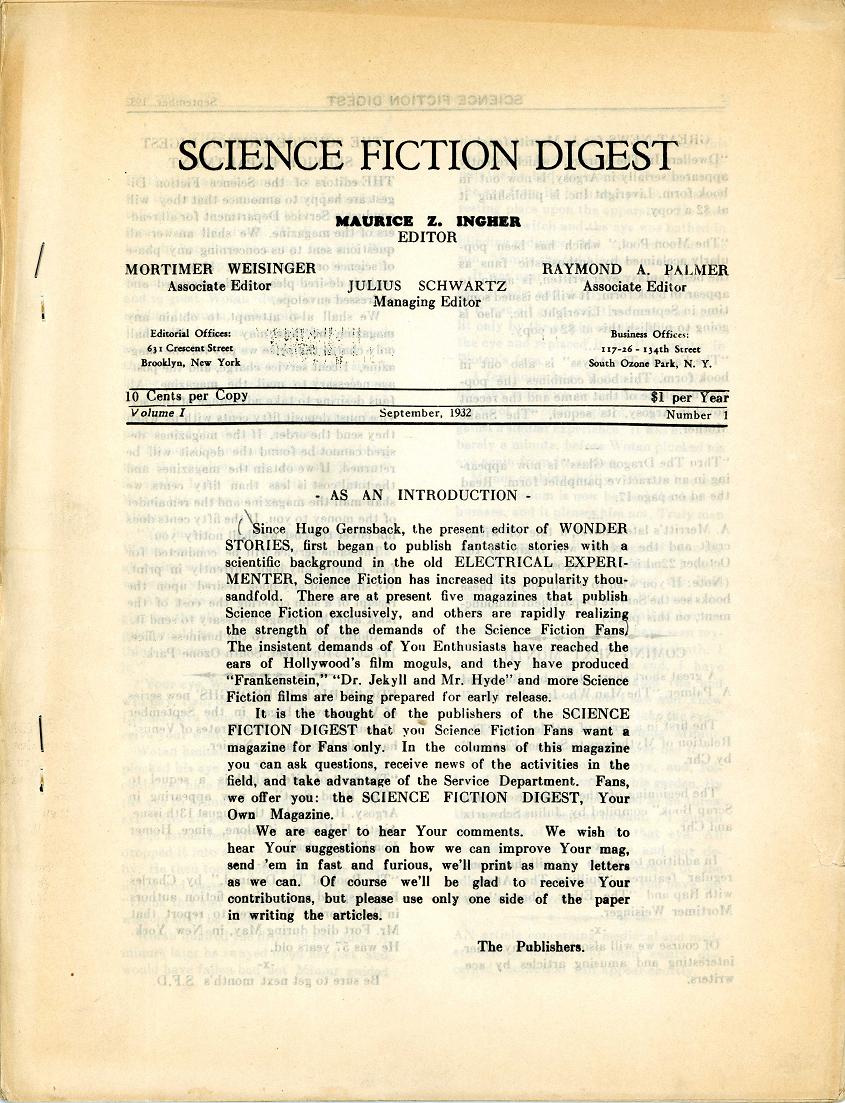

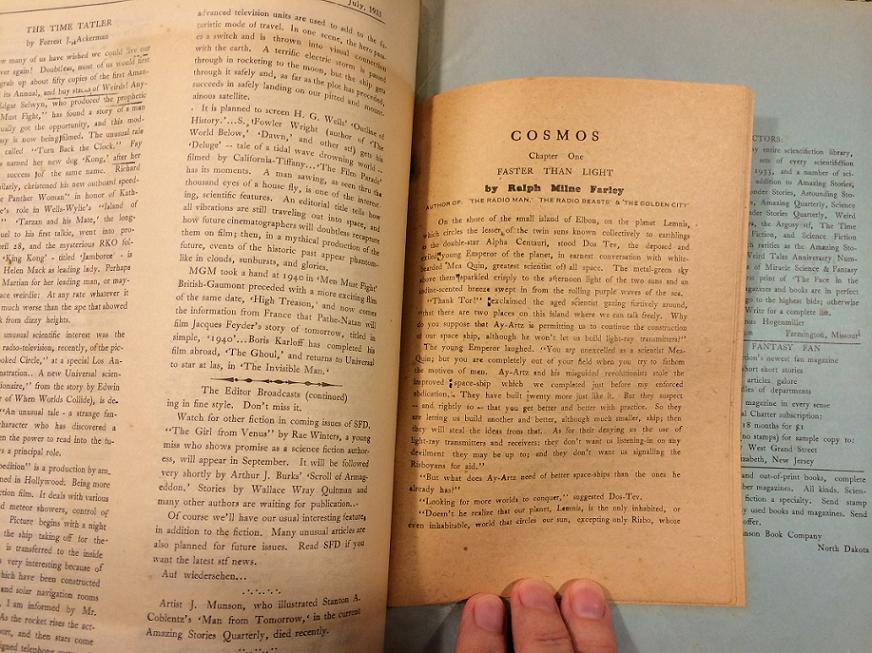

In April of 1933, Science Fiction Digest was already a well-established “fanzine,” published monthly and covering the fast-changing world of Science Fiction. Since its inception in September of 1932, the stapled, letter-sized pages had captured the voice of the expanding base of SF enthusiasts, featuring book and movie reviews, gossip about projects and upcoming publications, and some short original stories.

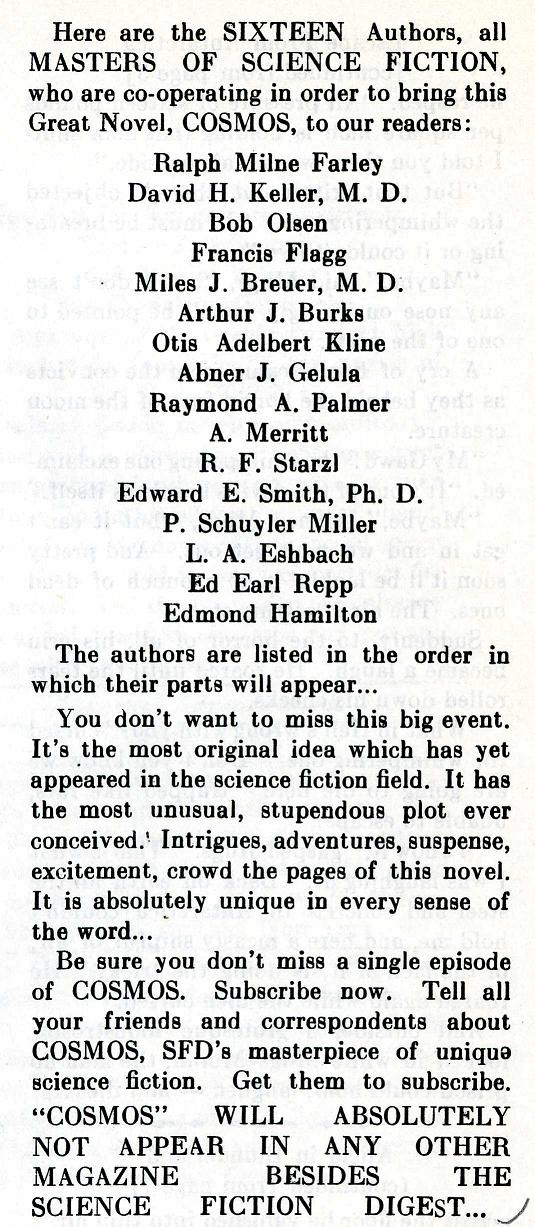

But the April ’33 issue marked a turning point for the ‘zine. The young staff led by Julius Schwartz (age 18) and Raymond A. Palmer (age 23) were anxious to expand into more ambitious publishing of fiction. With Conrad Ruppert (age 20) in the saddle as the new editor, a ground-breaking project was announced. Over the next two issues, the editors breathlessly described an epic project to produce the most ambitious serial novel ever attempted. No less than sixteen of science fiction’s most prominent writers would each contribute a chapter to Cosmos – each installment to appear as a supplement to the magazine’s monthly issues.

The staff of SFD made good on their promise to produce a remarkable piece of science fiction history. The impact of Cosmos on the future of the genre was profound, as the work played a key role in launching the careers of several of the most influential editors, publishers and authors in the field over the next 40 years. For this reason, Cosmos must be viewed as a unique success.

The staff of SFD made good on their promise to produce a remarkable piece of science fiction history. The impact of Cosmos on the future of the genre was profound, as the work played a key role in launching the careers of several of the most influential editors, publishers and authors in the field over the next 40 years. For this reason, Cosmos must be viewed as a unique success.

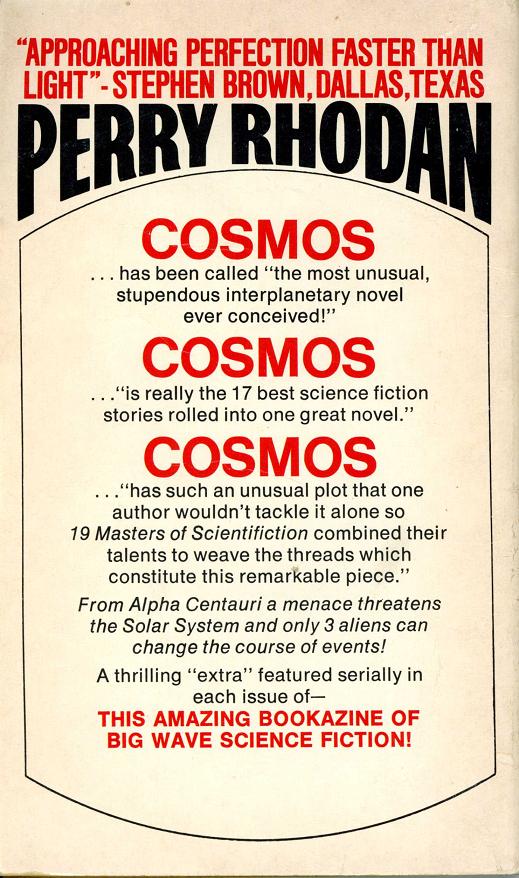

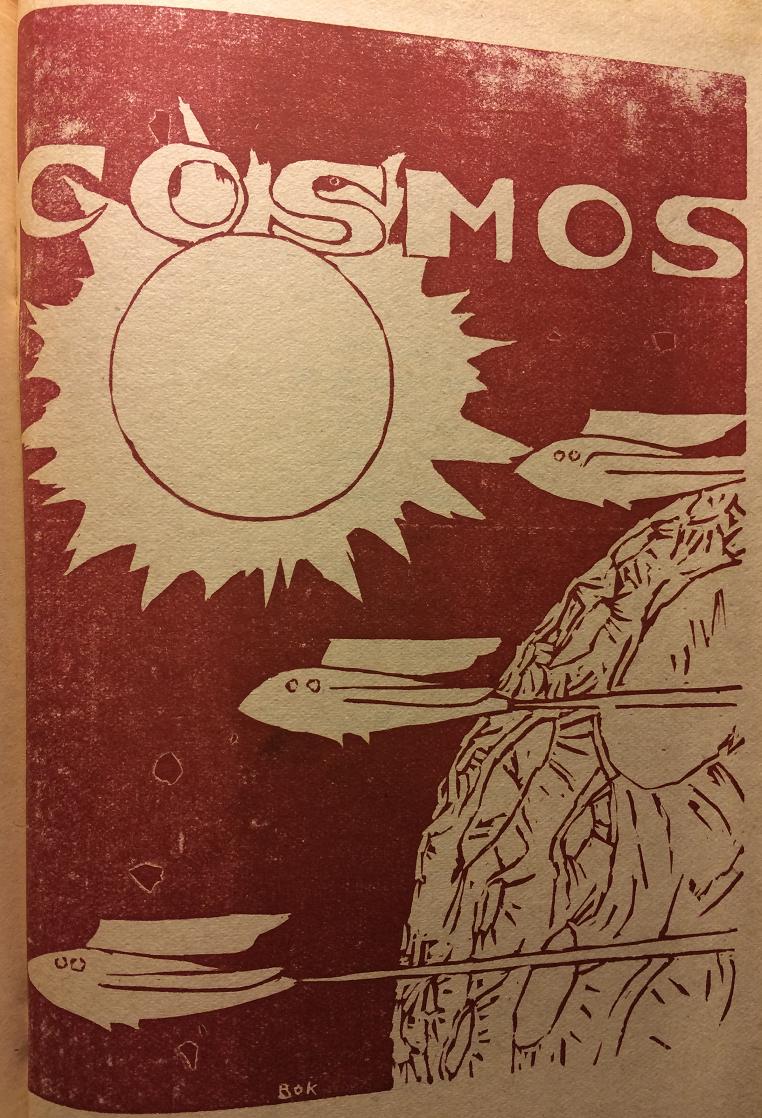

But the actual novel… ah, you had to ask. The full text has been generally unavailable to the reading public, as the chapters were spread over seventeen issues of Science Fiction Digest and Fantasy Magazine from 1933 through 1935. They were only republished once, but again in serial form in Forrest J Ackerman’s Perry Rhodan books from the 1970s. This lack of visibility has allowed the legend of Cosmos to grow in the annals of early SF.

For the first time, the entire novel is online. I suggest that it’s worth reading, but sadly not in general for its literary value. It’s a fascinating study of SF of the early thirties, and represents a snapshot of a genre that was evolving rapidly. The science fiction field was changing so fast that Cosmos became an outdated relic even before its last chapters were published. As you’d expect from such a collaboration, the tone and quality of the individual chapters varies widely, and the storyline struggles to remain cohesive. Much of the writing, even by some talented authors, is frankly god-awful – awful enough to provide comic relief, even. Exploring Cosmos is more a journey into the times in which it was created, and an opportunity to meet many of the people that shaped science fiction for the decades that followed.

As a small sample:

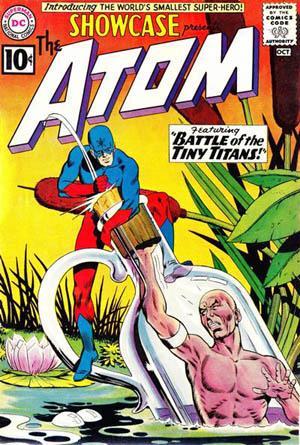

Julius Schwartz (Managing Editor) went on to become a principal editor at DC Comics, where he was responsible for the early development of iconic superheroes such as The Flash, and oversaw the revitalization of the Batman franchise in the 1960s and the Superman titles in the 1970s.

Julius Schwartz (Managing Editor) went on to become a principal editor at DC Comics, where he was responsible for the early development of iconic superheroes such as The Flash, and oversaw the revitalization of the Batman franchise in the 1960s and the Superman titles in the 1970s.

Raymond A. Palmer (Literary Editor) became the editor of Amazing Stories from 1938 to 1949, where he was instrumental in fostering the early careers of Isaac Asimov and other emergent leading authors. (He was referred for this job by Ralph Milne Farley, the author of the first chapter of Cosmos.) He later founded his own publishing companies and was influential in fomenting conversation and controversy through coverage of UFOs, spiritualism and other arcane topics. He notably was the first to publish in 1948 Kenneth Arnold’s seminal account of his encounter with “flying saucers.”

Raymond A. Palmer (Literary Editor) became the editor of Amazing Stories from 1938 to 1949, where he was instrumental in fostering the early careers of Isaac Asimov and other emergent leading authors. (He was referred for this job by Ralph Milne Farley, the author of the first chapter of Cosmos.) He later founded his own publishing companies and was influential in fomenting conversation and controversy through coverage of UFOs, spiritualism and other arcane topics. He notably was the first to publish in 1948 Kenneth Arnold’s seminal account of his encounter with “flying saucers.”

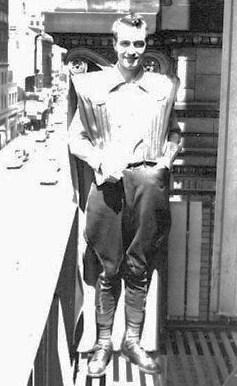

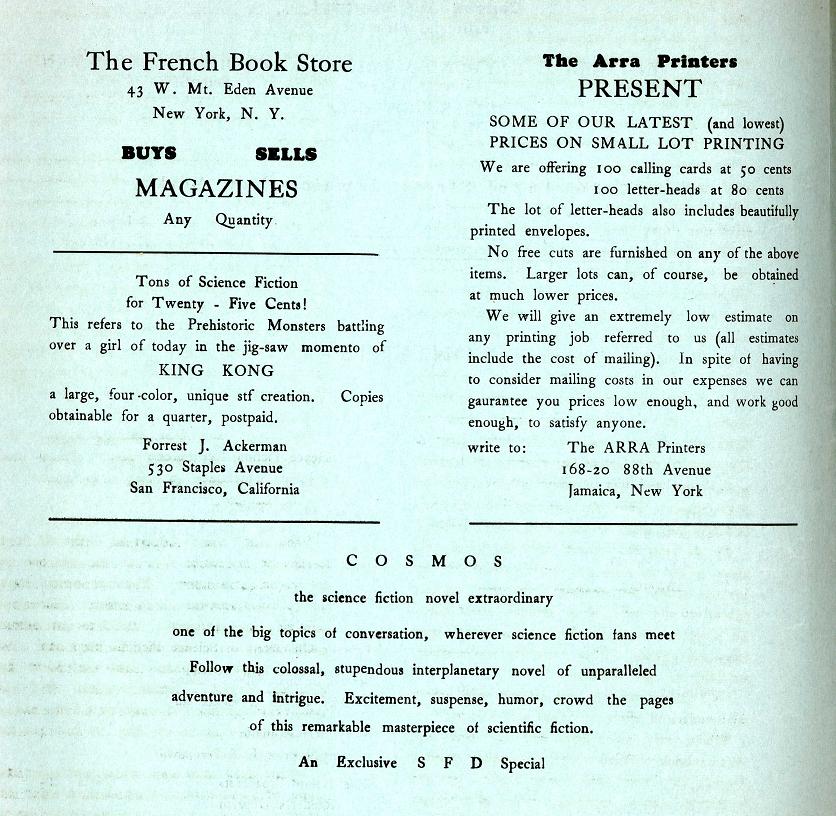

Forrest J Ackerman (“Scientifilm Editor”) became the most prominent science fiction fan of the 1940s through the 1990s. He founded the magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland in 1958, and his coverage of the “behind the scenes” artists creating science fiction and horror films has been cited as key early inspiration for such prominent personages as Peter Jackson, Steven Spielberg, Tim Burton, Stephen King and John Landis. His story is perhaps best captured in the documentary film The Sci-Fi Boys.

Forrest J Ackerman (“Scientifilm Editor”) became the most prominent science fiction fan of the 1940s through the 1990s. He founded the magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland in 1958, and his coverage of the “behind the scenes” artists creating science fiction and horror films has been cited as key early inspiration for such prominent personages as Peter Jackson, Steven Spielberg, Tim Burton, Stephen King and John Landis. His story is perhaps best captured in the documentary film The Sci-Fi Boys.

John W. Campbell, Jr. (author of Chapter Six) profoundly shaped the science fiction genre as the editor of Astounding Science Fiction and its successors from 1937 until his death in 1971. In his first months as editor, he published the first professional stories by Lester del Rey, A. E. van Vogt, Robert Heinlein and Theodore Sturgeon – resulting in what many regard as the beginning of the “Golden Age of Science Fiction.”

John W. Campbell, Jr. (author of Chapter Six) profoundly shaped the science fiction genre as the editor of Astounding Science Fiction and its successors from 1937 until his death in 1971. In his first months as editor, he published the first professional stories by Lester del Rey, A. E. van Vogt, Robert Heinlein and Theodore Sturgeon – resulting in what many regard as the beginning of the “Golden Age of Science Fiction.”

Mortimer Weisinger (Associate Editor) founded (with Julius Schwartz) first-ever literary agency specializing in science fiction, with several Cosmos authors as clients. He was named editor of Thrilling Wonder Stories in 1936, and managed a large number of other popular pulps. In March of 1941 he joined the company that was to become DC Comics, and over the succeeding 30 years he was responsible for editing Superman and Batman, and the creation of Aquaman, Green Arrow and other characters in the DC universe.

Mortimer Weisinger (Associate Editor) founded (with Julius Schwartz) first-ever literary agency specializing in science fiction, with several Cosmos authors as clients. He was named editor of Thrilling Wonder Stories in 1936, and managed a large number of other popular pulps. In March of 1941 he joined the company that was to become DC Comics, and over the succeeding 30 years he was responsible for editing Superman and Batman, and the creation of Aquaman, Green Arrow and other characters in the DC universe.

How Cosmos came to be…

Cosmos represents a very early and remarkable example of something we take for granted today: crowdsourced content development using social media. In this case, the “media” was paper sent though the US Post Office, and the “crowd” was formed in the letter columns of the science fiction pulps. Despite the obvious barriers, the intense curiosity and optimism of the organizers and participants carried the day.

Science fiction fandom got organized in the late 1920s and early 1930s largely due to publisher Hugo Gernsback’s policy of printing the addresses of fans who wrote letters to the seminal pulp Amazing Stories. Local “Scientifiction” clubs were formed and fans connected by mail with others across the country. The earliest fan publications resulted from these collaborations; the group which ran Science Fiction Digest in 1933 spanned New York, Milwaukee, and Los Angeles.

From the material in his columns and other writings, it seems clear that Raymond A. Palmer, then the Literary Editor of Science Fiction Digest, was the primary driving force behind Cosmos. This is also documented in a number of histories of the period. However, then-Editorial Director Conrad Ruppert suggests that the origin of the project was more of a collaborative effort among the editors. From “Tales of the Time Travelers,” John L. Coker, III, editor, Days of Wonder Publishers, 2009:

After the first year with Science Fiction Digest, I became editor, and some time later the title changed to Fantasy Magazine. It was during this time that we came up with the idea of doing a story about characters from different parts of the solar system and bringing them together at a central point. It was to be called Cosmos. Ray Palmer undertook the project and changed the original outline. He has a person from a nearby star come to the solar system in order to fight the invasion that was coming from his system.

Palmer tells his own version of events in the August, 1933 issue of Science Fiction Digest:

Of considerable interest is the origination and evolution of COSMOS. Some months before Liberty came out with its six author story, written for the movies, I conceived the idea of writing a science fiction novel with ten contributors. Accordingly the plot of COSMOS was evolved and a tentative ‘feeler’ sent to some of the more prominent stf authors. The instantaneous and enthusiastic response was so encouraging that plans were made to go ahead. Thus, the plot was sent to each author then interested and suggestions were made by each. The final result was a 13 part story. Thirteen authors were secured, with Ralph Milne Farley leading off. He was to write the ‘Venus’ part, using his popular Radio Planet characters. Suddenly he had a new idea, a hurried change was made and we found ourselves with a sixteen part story. ‘Venus’ was assigned to Otis Adelbert Kline when Farley wrote ‘Faster Than Light.’ Then, Amazing Stories editors, who have been taking an interest in the story, suggested that a part be inserted after part four, where they felt that an additional part was necessary to effect a more efficient cohesion. We were then able to include John W. Campbell, Jr.

An amazing situation developed here and it was discovered that many other prominent science fiction authors were also interested in contributing a part. Instead of having difficulty in securing enough contributors, we were experiencing the phenomenon of being literally mobbed by writers. And when I say writers, I mean the biggest of ‘big shots’ in the science fiction field. The reason for this situation arose through the system of ‘feelers’ sent to many authors. And so, we were faced with the possibility of ‘insulting’ several authors, which we did not desire to do. However, using the ‘first come, first served’ maxim, we got by this trouble without causing any bad feelings.

Edgar Rice Burroughs was unable to contribute because of other contracts. He has a novel to write for Argosy, and another serial for Blue Book.”

Palmer was a peculiar man. His story is perhaps best told in Fred Nadis’s fascinating (and overdue) biography, The Man From Mars: Ray Palmer’s Amazing Pulp Journey (Penguin Books, 2013). Palmer’s wikipedia page provides a terse portrait of this complex persona.

Nadis was able to locate some of the correspondence between Palmer and Lloyd Eshbach regarding the writing of Eshbach’s chapter of the novel (pg 18–19):

While literary editor at Science Fiction Digest, Palmer arranged one of the unique stunts of early science fiction, the novel Cosmos, which consisted of seventeen chapters assigned to different authors, printed as a serial. Palmer loosely set up the plots of the chapters and adjusted them as new sections were turned in, giving authors plenty of room for invention. The authors included some prominent pulpsters and SF writers…

Palmer was having a blast. He was dashing off letters to create Cosmos while also working as a sheet metal installer, writing his own pulp stories, sending out books from his lending library, and corresponding with at least twenty authors and other fans. In the spring of 1934, on Science Fiction Digest letterhead, Palmer wrote to Weird Tales author Lloyd Eshbach with his assignment for one of the concluding chapters of Cosmos, “The Horde of Elo Hava.” Palmer tapped out his instructions, “As for your part, you are to rescue the Neptune fleet, or ship, from the trap they have fallen into. You are out in space on the way to the battle-front as your part opens. You have just received a message from the commander of the earth ship saying that you are to proceed no further along your course, as it is also a death trap. (The lunarian, who has taken control on Luna, and is impersonating Dos-Tev, has sent these false courses.)” Palmer noted other difficulties that would plague the rescue and asked Eshbach to await word from another contributor to find out what “trap” the other space crew had fallen into. After succeeding in the rescue, “together you search space via radio for your brother and sister ships of the solar system, and meet nothing but dead silence! That ends your part.” He concluded his instructions with, “And now, go to it, and the sooner you finish, the better. Miller will be at it in a hurry too, so you won’t have long to wait.”

Palmer soon got a response from Eshbach, along with the new chapter, and a note declaring, “It’s finished – and I’m not one bit sorry! Between Flagg’s jelly characters and my desire to write something a bit out of the ordinary, I had one sweet time.” Eshbach encouraged Palmer to adjust the chapter as necessary to fit in with the rest of the narrative and went on to praise the chapter written by Abraham Merritt, “The Last Poet and the Robots.” Establishing himself as a fellow fan, Eshbach then complained about the latest issues of Amazing Stories and their reliance on reprints of Verne and Poe rather than fresh material…

More insight into the origin of Cosmos is captured in The Gernsback Days by Mike Ashley and Robert A.W. Lowndes (Wildside Press, 2004) (p. 216):

Although Science Fiction Digest carried fiction, that was not its main feature. Palmer, however, sought to remedy that by instigating a novelty in the form of a round-robin story to be published as a supplement. The story had the overall title of Cosmos and ran for seventeen chapters, from July 1933 to January 1935. Palmer provided the outline, which was rather old-hat space opera, and then reached agreement with sixteen other authors to write the series. The authors joined in for the fun of it, interested to see how their chapters fitted in with that preceding, and what problems they could set for others to solve. Since Palmer had set out the framework, the authors worked in advance on their sections before seeing the earlier chapters. Francis Flagg, for instance, had already plotted his chapter before he saw the opening chapter from Ralph Milne Farley. He put his thoughts in a letter to Ackerman:

A swell beginning, I think, tho on general principles I dislike emperors and princes as the heroes of stories. You will note I never use them in that sense… However, Farley has done a good opening chapter; it will test the rest of us to live up to it. Mine isn’t even written yet, tho plotted out somewhat. But I’ve two months to do it in. I’m looking forward to seeing Keller’s chapter. He CAN write and should give us something original. Farley’s will be a hard chapter to best for science, tho.

The full line-up of writers in Cosmos was awesome… They were all top names in the pulps, but to be able to bring together both Merritt and Smith in one serial was a bonanza for all fans. Cosmos is far from great science fiction, and has to be read in the manner in which it was written. Most of the chapters can stand on their own and Merritt’s in particular, “The Last Poet and the Robots” (April 1934), which was voted the most popular, is a gem of a story. It is some measure of the affinity that existed between science-fiction devotees that writers were willing to spend time and contribute stories free of charge to the fan press while, at the same time, they were instigating legal proceedings against Huge Gernsback for recovery of unpaid fees for stories. It is the clear distinction between work done for fun and that for profit.

It’s telling that these authors describe Cosmos as a “stunt” and a “novelty.” I can’t argue that the resulting novel suffers from severe flaws, and that Palmer was undoubtedly interested in the self-promotion that the project would generate – but the enthusiasm he portrayed at the onset leads me to believe that he aspired to create a great piece of fiction as well.

Harry Warner shared a particularly revealing anecdote regarding Palmer in his book, All Our Yesterdays (Advent:Publishers, Inc., 1969), which I think shows his focus and ambition (pp. 76–77):

When Ziff-Davis bought Amazing Stories in 1938, the new owners immediately fired T. O’Conor Sloane, tottery with age, as editor. Ralph Milne Farley [author of Chapter One of Cosmos] visited the Davis half of the ownership, saw that he didn’t know much about the magazine he now owned, and suggested Palmer as the proper person for the editorship. Davis asked Palmer to write a letter outlining his qualifications. Instead, at Farley’s suggestion, Palmer applied in person at the editorial offices in Chicago. An unidentified timekeeper chronicled the day’s events like this: Palmer arrived at 10:22 a.m., began to go through the pile of manuscripts on hand at 10:41 a.m., received complete charge of the magazine at 5:11 p.m., and got home at 9 p.m., having gone without food and drink for 27 hours. “Here at last,” Palmer said. “I had it in my power to do to my old hobby what I had always had the driving desire to do to it. I had in my hands the power to change, to destroy, to create, to re-make, at my own discretion.” He accepted only one of more than a hundred manuscripts left over from the Sloane regime, solicited another type of story from writers known to him, and arranged for a photographic cover because the new issue was due in two weeks and prozine artists were mostly in New York… Circulation figures were not officially published in those years, but Palmer claimed that Amazing was selling only 27,000 copies when he got hold of it, that his first issue sold 45,000 copies, that 75,000 copies were sold of the following issue, and that the figure eventually reached a peak of 185,000.

When Ziff-Davis bought Amazing Stories in 1938, the new owners immediately fired T. O’Conor Sloane, tottery with age, as editor. Ralph Milne Farley [author of Chapter One of Cosmos] visited the Davis half of the ownership, saw that he didn’t know much about the magazine he now owned, and suggested Palmer as the proper person for the editorship. Davis asked Palmer to write a letter outlining his qualifications. Instead, at Farley’s suggestion, Palmer applied in person at the editorial offices in Chicago. An unidentified timekeeper chronicled the day’s events like this: Palmer arrived at 10:22 a.m., began to go through the pile of manuscripts on hand at 10:41 a.m., received complete charge of the magazine at 5:11 p.m., and got home at 9 p.m., having gone without food and drink for 27 hours. “Here at last,” Palmer said. “I had it in my power to do to my old hobby what I had always had the driving desire to do to it. I had in my hands the power to change, to destroy, to create, to re-make, at my own discretion.” He accepted only one of more than a hundred manuscripts left over from the Sloane regime, solicited another type of story from writers known to him, and arranged for a photographic cover because the new issue was due in two weeks and prozine artists were mostly in New York… Circulation figures were not officially published in those years, but Palmer claimed that Amazing was selling only 27,000 copies when he got hold of it, that his first issue sold 45,000 copies, that 75,000 copies were sold of the following issue, and that the figure eventually reached a peak of 185,000.

The vital connection between Cosmos and Palmer’s later career were manifest in Farley’s recommendation for Rap’s first professional job in publishing, and in his ability to quickly gather quality material from the leading writers of the day. Cosmos the novel was already becoming obscure, as indicated by the following note also from All Our Yesterdays (p. 59):

…yet the receipts at the first worldcon [World Science Fiction Convention] auction in 1939 totaled only $75; included in this figure were the winning bids for such things as the original manuscripts of a Weinbaum novel, a Howard story, and “Cosmos,” the pro chain story; unpublished Wesso and Paul cover art; early issues of Time Traveler and Science Fiction Digest; and an inundation of less heady material.

But the relationships established through the creation of Cosmos continued to shape science fiction for years and decades that followed. Through his connection to Julius Schwartz, Palmer’s name achieved immortality in a different way: he became a superhero. In “Tales of the Time Travelers,” in Schwartz’s autobiographical essay “Strange Schwartz Stories from DC Comics,” he describes his resurrection of The Flash and his key interventions in the Superman franchise during the 1950s. He also adds:

Incidentally, one little side note, another character that I brought back was The Atom. The original Atom from the golden age was just a small-sized guy with a terrific punch, no super powers. When I did The Atom, I worked out a story where a human being could shrink himself in size to any size he wants. His normal small size would be six inches. Super heroes ought to have civilian identities and costumed identities. I thought about my friend Raymond Palmer, who had worked on Science Fiction Digest and was the editor of Amazing Stories. He had had an accident when he was a youngster, and something happened to his back. He never grew more than four feel six inches tall. So I called Ray and asked if he’d mind if I call The Atom “Ray Palmer?” That’s how he got his name. By the way, the column that Ray Palmer wrote for Science Fiction Digest in the early-1930s was called “Spilling the Atoms.”

Incidentally, one little side note, another character that I brought back was The Atom. The original Atom from the golden age was just a small-sized guy with a terrific punch, no super powers. When I did The Atom, I worked out a story where a human being could shrink himself in size to any size he wants. His normal small size would be six inches. Super heroes ought to have civilian identities and costumed identities. I thought about my friend Raymond Palmer, who had worked on Science Fiction Digest and was the editor of Amazing Stories. He had had an accident when he was a youngster, and something happened to his back. He never grew more than four feel six inches tall. So I called Ray and asked if he’d mind if I call The Atom “Ray Palmer?” That’s how he got his name. By the way, the column that Ray Palmer wrote for Science Fiction Digest in the early-1930s was called “Spilling the Atoms.”

To be continued…

Further installments of this series will cover the evolution of Cosmos and the world around it as the chapters were published during 1933 and 1934. I also hope to publish more content from early science fiction fanzines along a variety of themes. I welcome feedback and input on subjects of interest.

[Sources for this article are listed here. All images from Science Fiction Digest, Fantasy Magazine and other pulps/comics are scans from my personal collection. Photographs are used by permission of Robert A. Madle. You can contact the author here.]