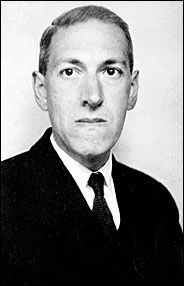

At the Mountains of Madness

by H.P. Lovecraft

(1890-1937)

By Nader Elhefnawy

I must admit that I’m a relative latecomer to the works of H.P. Lovecraft. I always thought of him as a horror writer, and had little interest in the genre, while not being all that clear on his contribution to it. Additionally, much of the writing I happened to encounter about him at the time was rather vague about his actual production, and at any rate, not at all complimentary.

Nonetheless, as the years went on I kept encountering writers drawing on his legacy, Charles Stross, Paul di Filippo and Elizabeth Bear to name but a few (and of course, Fritz Leiber). In the Hellboy comics and the movies Guillermo del Toro made out of them I saw his concepts rendered visually. Reading Robert Howard gave me direct contact with Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos (as in the Bran Mak Morn tale “Worms of the Earth”).

In the end, it seemed that I’d have to go back and read Lovecraft for myself, just as I’d made a point of familiarizing myself with other foundational writers of speculative fiction from Isaac Asimov to Roger Zelazny. I picked for my first story Lovecraft’s novella “At the Mountains of Madness,” mainly because Stross mentioned its events as part of the premise for his novelette “A Colder War,” and because I understood that it played a special role within the Cthulhu mythos, clarifying what was only hinted at elsewhere about his fictional meta-legend about an ancient, elder race worshipped in secret, violent cults across the margins of history and connected with mysterious sites around the globe. (Lovecraft scholar S.T. Joshi has also characterized “Mountains” as his “most ambitious attempt at ‘non-supernatural cosmic art'” and “the greatest of his attempts to fuse weird fiction and science fiction.”)

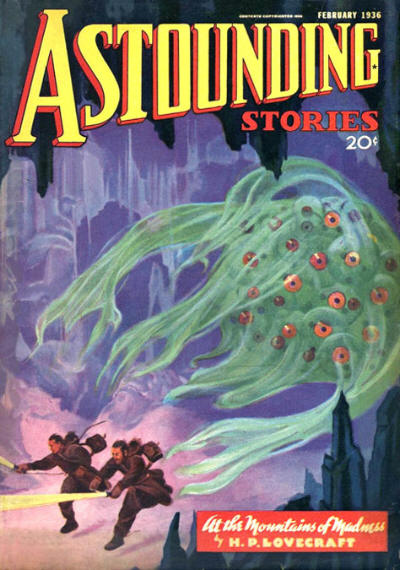

“At the Mountains of Madness” first appeared in serial form in Astounding Stories, from February to April of 1936 (after its rejection by Weird Tales). The narrative opens with geology professor William Dyer recounting his participation in Miskatonic University’s expedition to Antarctica aboard the allusively named ship Arthur Gordon Pym. Shortly after arrival a party splits off from the expedition and proceeds into the interior of the continent, where they discover a mountain chain taller than the Himalayas. They also find a ruined, ancient city in these mountains where no human could ever have lived.

“At the Mountains of Madness” first appeared in serial form in Astounding Stories, from February to April of 1936 (after its rejection by Weird Tales). The narrative opens with geology professor William Dyer recounting his participation in Miskatonic University’s expedition to Antarctica aboard the allusively named ship Arthur Gordon Pym. Shortly after arrival a party splits off from the expedition and proceeds into the interior of the continent, where they discover a mountain chain taller than the Himalayas. They also find a ruined, ancient city in these mountains where no human could ever have lived.

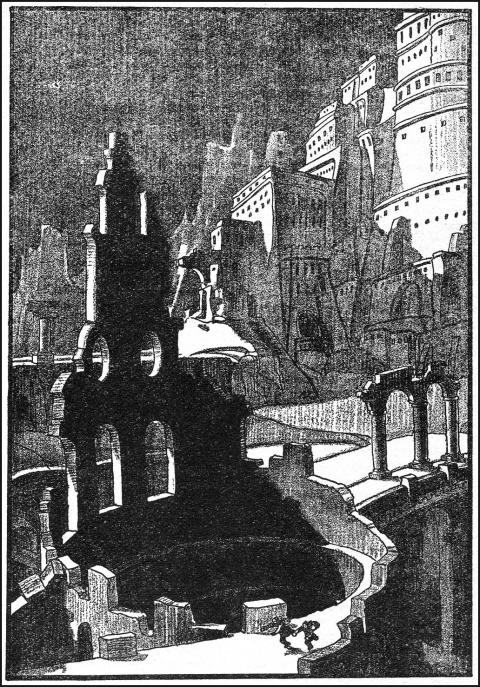

After they communicate this startling discovery, the main expedition loses contact with the party, leading Dyer and another member of the team, Danforth, to fly out to the scene in a plane the expedition brought with them to investigate. There, in carvings on the city’s walls, they discover the story of the city’s builders, referred to in the story as the “Old Ones,” a saga of the rise and fall of a great civilization echoing that of many a human culture revealing the origins of many of the “gods” of the Cthulhu mythos–and a great danger to humanity lurking within the region. Danforth is shattered by the experience, while Dyer (who narrates the story after coming home) speaks of what he has seen only to dissuade further exploration of the Antarctic.

A description of Lovecraft’s work can read like a list of those charges critics who don’t read much science fiction routinely make against the genre. The social world we live in, with all its concerns, is absent, with many a reader specifically noting the exclusion of references to money and sex, and the very narrow range of characters, going beyond the general absence of women to the tendency to focus almost solely on prim gentlemen much like Lovecraft himself. There isn’t much in the way of plot or action either, neither of these being of great interest to this author, and those looking for the “character-driven” fiction conventionally expected of authors will be disappointed both by the paucity of character development, and the passivity of the protagonists. As Michel Houellebecq (whose own fiction uncannily parallels his reading of many of Lovecraft’s attitudes and preoccupations, in spite of a vast difference in subject matter) has noted, Lovecraft’s characters are “silent, motionless, utterly powerless, paralyzed observers,” like a sleeper unable to wake up from a nightmare. In line with this approach there is instead an abundance of thick description of psychological states (the range of which is fairly limited), and of physical settings (with results often no better).

In short, Lovecraft’s work dispenses with much of what ordinarily appeals about fiction, and it doesn’t help that the prose is so dry, drier even than everything I’ve said so far about the thinness of characters, the avoidance of so much of the stuff of human life and the lack of action would suggest. He had a propensity for “heavily ornate” writing, for “immensely complex sentences” cluttered with an overabundance of adjectives, for sheer hyperbole, for “archaic” choices of vocabulary, as Philip A. Shreffler has noted, giving it a turgid feel rarely found in twentieth century literature.

“Mountains” is no exception to this pattern, and arguably suffers more from those deficiencies than other Lovecraft works–for instance, “The Call of Cthulhu” (to which I turned later)–because of its exceptional length, and its particular story structure. Dyer’s journey to the titular mountains is essentially an overlong set-up for the revelation of the Big Secret, and unsurprisingly it lacks the sense of intricate investigation, or the wide-ranging and relatively well-developed incidents, that gave that particular story its interest. I wouldn’t characterize myself as a particularly impatient reader, however I did find my patience overtaxed, and was repeatedly tempted to skim instead of read in the first fifty pages.

“Mountains” is no exception to this pattern, and arguably suffers more from those deficiencies than other Lovecraft works–for instance, “The Call of Cthulhu” (to which I turned later)–because of its exceptional length, and its particular story structure. Dyer’s journey to the titular mountains is essentially an overlong set-up for the revelation of the Big Secret, and unsurprisingly it lacks the sense of intricate investigation, or the wide-ranging and relatively well-developed incidents, that gave that particular story its interest. I wouldn’t characterize myself as a particularly impatient reader, however I did find my patience overtaxed, and was repeatedly tempted to skim instead of read in the first fifty pages.

Nonetheless, I plowed on, and the story became considerably more readable when Dyer and Danforth finally arrived in the city of the Old Ones. Unsurprisingly, Lovecraft is better with interiors than exteriors. His meticulousness in relating scientific and technical detail lends the narrative far more verisimilitude than I would have expected. He also has a knack for dropping hints that evoke immensities (not on a par with Frank Herbert’s, for instance, but effective enough), and it is in the immensities of the Old Ones’ tale that the story really started to hold my attention. The narrative certainly has its peculiarities, and even its weaknesses. The tale of the Old Ones is essentially Spenglerian, recapitulating a cycle of civilizational rise and fall that will seem frustratingly short on cause and effect, frankly irrational, crypto-racist (or at least, crypto-racialist), and to borrow Michael Moorcock’s phrasing, heavy on the “negative romanticism found in much Nazi art.” Yet, Lovecraft’s careful conception of the Old Ones pays off here, and for fans of the writer’s other stories, there is the intrinsic interest of the truth at the bottom of the mythos (though at the same time, I wonder if the demystification of the Old Ones, and the profound shift in attitude toward them seen in this story, don’t diminish its appeal for some).

These ideas, not just long out of fashion but now conventionally viewed with great distaste, are far less likely to engage intellectually now than then. Still, the drama remains a grand one in its scope and sweep, and its final act retains a charge in its implications for Dyer, Danforth and their whole species–an accident whose survival is far more precarious than its members realize. In that, Lovecraft was not antique but perhaps ahead of his time, and if, as Moorcock has observed, he appeals to us when we are feeling morbid, that may be because his morbidity was just an especially intense perception of the morbidity of the contemporary world that he so badly wanted to turn away from, and in which we have been living ever since.